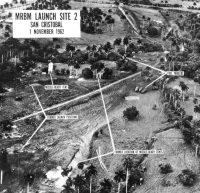

October 14, 1962, witnessed the start of one of the most potentially devastating moments in history, when the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Photographs taken by a high-altitude U-2 spy plane offered clear evidence that Soviet medium-range missiles — capable of carrying nuclear warheads — were now stationed 90 miles off the American coastline.

Tensions between the U.S. and the USSR over Cuba had been steadily increasing since the failed April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. Though the invasion did not succeed, Castro was convinced that the United States would try again, and set out to get more military assistance from the Soviet Union. During the next year, the number of Soviet advisers in Cuba rose to more than 20,000.

Two days after the pictures were taken and analyzed by intelligence officers, they were presented to President Kennedy. During the next two weeks, a tense standoff between two superpowers ensued as a fearful world awaited the outcome. Moncrieff Spear served at the Operations Center during that critical time; he was interviewed by Thomas Dunnigan beginning in April 1993.

You can also read Helmut Sonnenfeldt’s account from the State Department and the White House and about what was happening in Moscow at the time of the Crisis.

Soviet Nukes in Cuba

Q: What did a watch team do?

SPEAR: Well, it had several functions. One was simply to monitor the cable traffic coming in from the posts overseas. There were so-called editors on the teams responsible for pulling these cables together and preparing précis of these cables and piecing them together to give a running story of these developments. This then went into a morning summary, which was placed on the desk of the Secretary of State. Copies went over to the White House and to all of the other senior officers in the Department….

I wound up as the Acting Director [of the Operations Center] during the Cuban Missile Crisis because the Director was off on one of those Presidential Task Force teams in Brazil. We had known earlier that there were military developments going on in Cuba and a Code Word had been set up which would indicate that the Cuban and Soviet forces there had an offensive missile capability.

I remember being called at home one evening by the Senior Watch Officer, who repeated this Code Word to me. He then said that the Under Secretary for Management wanted to take over our Conference Room for a major briefing. So I went rushing down to the Operations Center and brought in one of the officers from the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs who had been following this very closely. He, in effect, told me that they had discovered this offensive, military capability. This was during the week before the President made his speech and the whole thing became public.

There was intense activity going on in the Operations Center at that time. I remember that the President’s speech kept going through one draft after another. Unfortunately, the Department’s communications capability to get the text of the speech out to various, important, allied capitals simply broke down under the strain.

I remember one evening, just shortly before the President’s speech when the Under Secretary for Management came in. It turned out that they had been down in the Telegraph Branch just below us there, literally pulling tapes right out of the machines there trying to get the changes put in and get this speech sent out. Incidentally, as a result of that, the Department later obtained greatly enhanced communications facilities and was brought into the middle of the 20th century in terms of its communications capability.

You may recall that Chester Bowles had been a very senior official in the State Department in the early days of the Kennedy Administration. Subsequently, he was replaced by Averell Harriman and was given a rather grandiose title as the President’s personal representative to all sorts of Third World countries. He had been traveling around Africa at the time….

We had been sending a morning summary to Bowles but, on instructions from on high, it was largely a recapitulation of The New York Times that morning. It was not very highly classified. But suddenly, when we began to look for support in the United Nations, to back Adlai Stevenson’s efforts up there, we started to put some really “hot stuff” into the Bowles’ morning summary, which skyrocketed up in classification.

“Suddenly, there came this report of a missile headed for the United States.”

I remember, in the early days of the Cuban Missile crisis, that we were all working about 18 or 20 hours a day. At one point all of us were absolutely transfixed. We had a Watch Team over in the Pentagon with the Battle Staff there. They would give us reports of the various megatonnages [of nuclear weapons] which CINCSAC [Commander in Chief, Strategic Air Command] had on first strike and second strike availability. Needless to say, this was very sobering, indeed.

Suddenly, there came this report of a missile headed for the United States. It was quickly checked and turned out that it was coming up from the South Pole. It was obviously a glitch in the radars and detection mechanism. But it gave everybody one hell of a scare.

The role of the Navy in the quarantine line around Cuba to intercept Soviet ships bringing missiles to Cuba is well known. At that time it was uncertain as to whether there were actually nuclear warheads in Cuba or whether they simply had the missiles there.

A less well-known aspect of the crisis was the interdiction effort we ran diplomatically to prevent these warheads from being flown in. We had reports of a number of Soviet flights originating in the Black Sea area, which then flew via airports in North Africa, crossed the South Atlantic Ocean from West Africa to the bulge of Brazil, and then went up into the Caribbean area.

Under instructions from the Department, our ambassadors in all of those North African posts and up and down the Caribbean made very strong representations to the local governments. In due course, we got these flights stopped, although one of them, as I recall, got as far as Guyana [northern South America] before it was finally stopped.

“One feisty Scandinavian skipper, in effect, told the U. S. Navy to go to hell.”

There was also a great deal of activity going on up at the UN, as our UN Mission presented the case against the Soviets. They used aerial photographs and so forth to bring about UN condemnation. We also mounted a major effort in the Organization of American States to get Latin American states to support our activities there, too.

Going back to the Naval quarantine, I should mention that we were getting all sorts of reports, from various ships’ agents saying that, rather than being stopped by the U. S. Navy and running the possibility of an international incident, they would be very happy to have their ships diverted to U. S. or friendly ports, where they could be inspected.

However, we couldn’t get any information out of the Pentagon as to where these merchant ships were. You may recall that this led to a confrontation between Secretary of Defense McNamara and Admiral George Anderson [then Chief of Naval Operations] which was rather well publicized at the time. I was working very hard, trying to get this information.

My opposite number in the National Military Command Center, the Pentagon’s crisis center, was a naval officer. Because of his naval officer’s uniform, he was able to go into the “Flag Plot” [in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations], make some notes on just where all these ships were and get some of this information back to us. In turn, we were able to get some of these merchant ships diverted and so avoid incidents, perhaps having the ships fired on, and so forth.

There had been one feisty Scandinavian skipper who, in effect, told the U. S. Navy to go to hell. The Navy had to be ordered not to fire on him.

After the message was received that Khrushchev had agreed to remove the missiles, the crisis was far from over as far as the Operations Center was concerned. There was the matter of getting Cuban diplomats up to the UN to continue these negotiations.

Because we had air and ground forces ready for an invasion of Cuba, we wanted to be sure that none of the planes bearing these diplomats, or Soviet diplomats going into Cuba, were shot down by our forces. This required very close coordination between the Operations Center and the National Military Command Center.

There are two other footnotes I would add to this. One was that it was absolutely fascinating to work the Department at that time. No more than about 35 individuals were actually doing anything related to the crisis during this period. Of course, we were heavily involved with the people in Political-Military Affairs and [Deputy Under Secretary for Political Affairs U. Alexis] “Alex” Johnson. Sometimes you were dealing with an Assistant Secretary.

At other times the whole structure of a bureau fell away and we found ourselves, for example, dealing with one of the desk officers in the Aviation Division, when it came to finding out how to get clearances for these aircraft to move diplomats into and out of Cuba. It was really weird.

Months afterwards I would run into colleagues in the hall who would keep asking me, “What went on during this time?” The rest of the Department simply seemed not to be functioning….

There was a lighter side to the Cuban Missile crisis. It was a ghastly affair, because I had been working 18-20 hours a day. I’d come home in the wee hours of the morning, get four or five hours of sleep, and then have to go back to the Department. As a matter of fact, I lost about six pounds in a week or two.

[My wife] Lois was working at the time, so she would be gone by the time I would get up. After about the second week, I found a note pinned to my pillow, saying, “I do need to see you urgently on several matters. Can we make a date to have lunch together?”