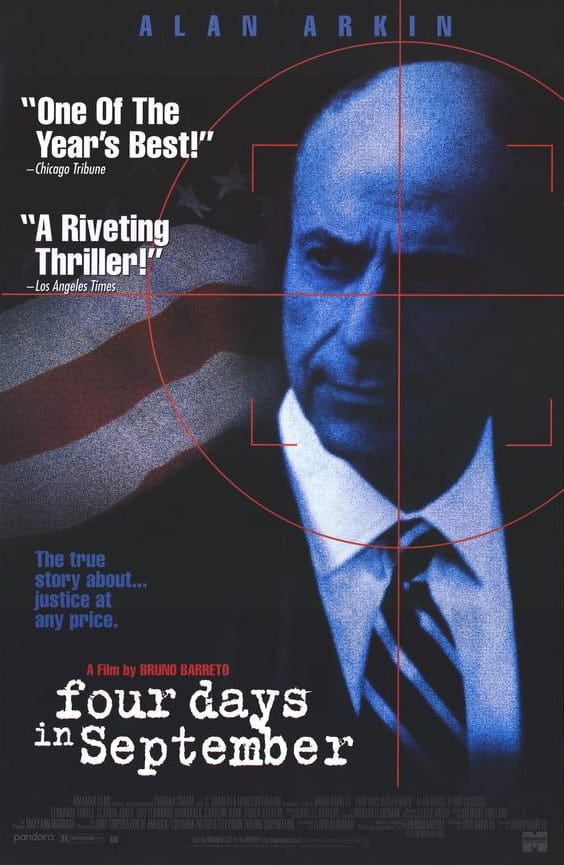

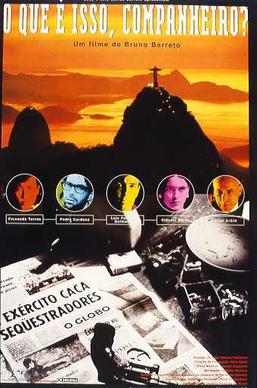

It sounds like something out of Hollywood. Indeed, it was made into a Brazilian movie in 1997 with Alan Arkin (in his pre-Argo days). Charles Burke Elbrick, U.S. Ambassador to Brazil, was kidnapped and held for four days in September 1969. What made the incident so strange was that Fernando Gabeira, a member of the guerrilla group called the Revolutionary Movement 8th of October (MR8) and a key figure in Elbrick’s kidnapping, later wrote a book called O que é isso, companheiro? (“What’s this, comrade?”) in which he discusses the kidnapping and his armed resistance to the military dictatorship. Gabeira lived in exile for several years and was elected federal deputy for Rio in 1995. In a 2009 interview he said he was “in error” in kidnapping Elbrick; however, he is still not allowed a visa to travel to the U.S. The movie Four Days in September was nominated for several awards, including Best Foreign Language Film by the Academy Awards. In these excerpts, Elbrick’s widow Elvira discusses her husband’s kidnapping and life after his release, as well as how she “got even” with Richard Nixon.

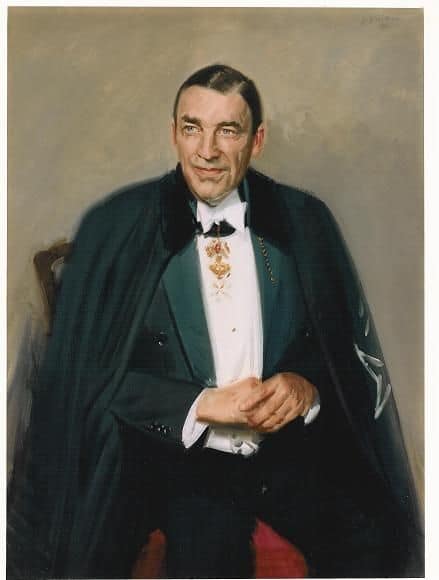

Burke Elbrick was born in 1908 in Louisville, Kentucky and joined the Foreign Service in 1931. His posts included Poland, Cuba, Portugal, Yugoslavia, and Brazil. He suffered severe medical complications from the beatings he endured while a hostage. He eventually died in 1983. Elvira was interviewed in 1986 by Jewell Fenzi as part of the Spouse Oral History Series. For one former hostage’s critical view of U.S. policy, see Mike Hoyt’s piece. Read about when the U.S. Ambassador was kidnapped at a reception in Bogota.

Burke was pushed to the floor and a tarpaulin put over his head

ELBRICK: Well, it all started…we were in Yugoslavia five and a half years and we were delighted to go to Brazil. We had never been in South America, always in Europe. So we thought, “Oh, this is wonderful after being in a communist country to go to carnivals in Copacabana and meet the Brazilians, an interesting continent. We had just arrived, we’d been there 57 days and hadn’t even unpacked all of our suitcases, but we had a very busy life as everybody does from the juniors on up to the seniors. When you first arrive you’re very busy….

About a week later we were still with our tongues hanging out from exhaustion with so much going on and Burke heaved a sigh of relief and said, “Isn’t this wonderful? We can have lunch together alone,” on one of the many terraces — a huge house, twice the size of the White House painted pink, 23 servants in the house and 12 Marines – enormous. A number of people slept in our house plus all the guests so we were never alone and this was a great day, we had a free lunch. We had a very pleasant lunch together. And one of the butlers came in and said, “There are a lot of photographers and press in the foyer downstairs.” Burke said, “I don’t want to,” because they kept plaguing us – needling Burke to be interviewed. He hated publicity. And I said, “Oh, Burke, they’ve come again, they have to make their own living. Do go down for about ten minutes to talk with them and they’ll just splash a picture — just say ‘hello’ to them, ‘and how are you, and how are your children, your wife’and then you can get in your car and go to your office.”

So he did, and I went downstairs to help put on a big bazaar that all the diplomatic missions in Brazil were putting on to raise money for the poor. We had a booth – it was all new to me, it wasn’t my idea but it had been done before. We had 311 pairs of Levis in the basement of the house, cupcakes – heaven knows how many of those – and Revlon products, that’s what the Americans were going to sell in their booth…. I went down to help tag with an assortment of ladies in the Embassy – 20 at a time would come for a couple of hours throughout the day. We all worked together.

Suddenly my secretary came downstairs, and I said, “Don’t disturb me because I’m tagging these Levis and I’ve got cupcake frosting on my fingers, and I’ll be up later. What’s the matter?” “No, no, it’s very urgent. It’s an emergency.” So I said, “All right.”

So I went upstairs and she said, “Your husband has just been kidnapped.” And I said, “What! We just had lunch together.” I said, “When?” And she said, “About three minutes after he entered his limousine to go back to his office.”

He was caught on a side street, intercepted by a Volkswagen, and they dragged the chauffeur out of the limousine and tore out the telephone, put a tarpaulin on Burke in the back of the car, and two of them with rifles at his neck, and the chauffeur was squeezed – he was very tiny, a Portuguese chauffeur, very small — had to sit on the cushion to drive this big Cadillac limousine – so they pushed him into the middle and one got behind the wheel and the other one by the door beside the chauffeur and said, “Go.”

Burke was pushed to the floor and as I said, with a tarpaulin over his head. So then they went on and on and on for quite a long time – close to two hours – and later Burke told me that he had read enough of Agatha Christie and Alfred Hitchcock to know that sometimes by hearing you could judge where you were going by the sounds that you heard – the general direction.

So a tunnel, or a mountain, or a flat area, he could feel the automobile moving – a hollow space like a tunnel he remembered particularly – the sound was very different. So he was able later when he was liberated to guide the — well, they’d discovered where he was in the meantime, where he had been incarcerated. They examined, with Burke present, where he was up in a shack in the mountains and he led them exactly because of the sounds. So anyway it was just a very short time that they kept him — it was just five days and six nights.

Q: But it didn’t seem short at the time, I’m sure.

ELBRICK: Well, I was in — I don’t know — a daze I think and I never asked for television or radio and they took them out and I didn’t even notice they were missing. I carried on; I had people in as usual and carried on with my life as best I could. But I was amazed. Oh, they called from all over the world, The London Times, and the Paris Soir, Roma or whatever in Italy, I’ve forgotten all of these [newspapers]. And I thought it was my children so I went to the telephone because they were in Europe, both of them; one was in the mountains of Montenegro doing a film with Mel Brooks and they couldn’t reach her for three days. My son was in London. So I rushed to the telephone and then the newspaper people would say, “What kind of toothpaste did you use when you went to bed last night?” and “What color nightgown?” and “What kind of a breakfast did you have, and did you sleep, and what did you do in the meantime?” The most ridiculous questions….

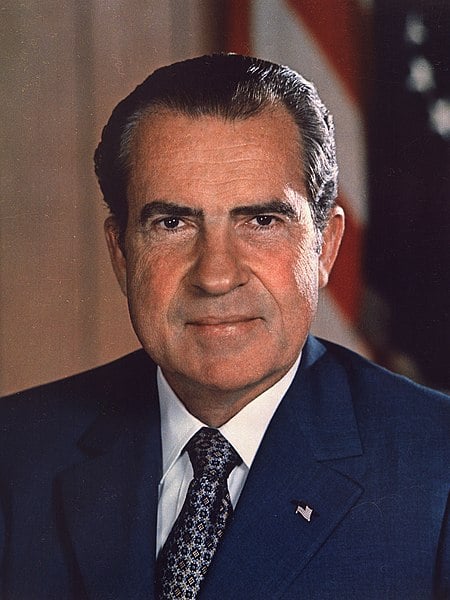

Nixon gave an order – he was the one who appointed Burke – when Burke was kidnapped he gave an order to the State Department, Rogers at that time, and the Secretary of Defense at the Pentagon, and the White House, were to lay off the Elbrick case because he didn’t want America to be involved with Brazilian terrorism and revolutionaries and therefore they were not to do anything to help liberate Burke. [The late Sheldon T. Mills, former DCM in Rio de Janeiro, maintains efforts were made to secure Elbrick’s release. Mrs. Elbrick, apparently, was never informed.]

Q: This came from President Nixon?

ELBRICK: This was President Nixon’s orders. So there wasn’t a word. I wasn’t phoned, I didn’t get a letter from the President. I thought at least he would call and say, “Would you like your children? I’ll send a plane for them.” I would have said no, that I didn’t want them to be involved in this in case they blew up the house or did something crazy because you never know what they’re going to do. But nothing, no word….

The Brazilian government for some unknown reason other than they thought it was very strange that the United States President had not done anything to help this man, innocent victim, 57 days in the country who knew nothing about Brazilian politics or terrorism – he hadn’t had time to be briefed you see, in that short a period under two months – so anyway the Brazilian government for some unknown reason took pity on Burke and they surrendered to the wishes of the revolutionary, which was against their principles because it was the same thing exactly as in Persia five or six years ago when all that happened at our embassy there, Khomeini and the students.

So the revolutionaries were against the government and it was very demeaning for the Brazilian government, a military junta – a general was president – to surrender to the wishes of the revolutionaries to liberate this American. But they did it and the revolutionaries required 15 leaders of pockets of revolutionaries and in Brazil, it being an enormous country, it was very hard to find them, to get them….

That was the ransom, to get these leaders and it was very, very hard to find them and this took time. But finally they did and they went to — I’ve forgotten where they went, I think they went to Saudi Arabia, some of them — there were 15 anyway — and a few went to Mexico.

They are all dead now except two, well that’s another story I’ll tell you about that just recently came to my view. This man [Fernando Gabeira] wants to interview me who was one of the leaders of Burke’s kidnapping who is now free and going into politics in Brazil. He has filtered back to his country, had been living in Sweden — I’ve forgotten, some other…I think France and had a book written about Burke and he was the one that opened the door of the shack to say, “Hello, comrade, who have you got there?” And they said, “It’s the American Ambassador.”

This was the man who wrote the book who is now in politics in Rio and wants to be governor of Rio…. He has made a fortune with this book about the incident because there’s a new government, so he was able to get back to his country and he then made a movie…about the kidnapping of this American. And now he’s in politics. It’s really rather funny….

“They tortured and beat him terribly”

I don’t think I really absorbed it at the time; it’s sort of like a death, a little bit worse because… the fear of the unknown was the worst…. And I began to think I would rather hear that he was dead and not suffering wherever he was because they tortured him and they beat him terribly. They put him in front of an electric light bulb in a garage with a white wall on a three-legged stool all night long that first night — he was taken at 10 minutes past 3:00 after lunch and it went on all night long. They gave him a book of Ho Chi Minh to read….

He spoke fluent Portuguese, which was in his favor, with the men in this shack and a man sat on the floor all the time, they rotated and let him go to the bathroom and that was about it — a cot, a table and a chair, and a paperback of Ho Chi Minh to read and gave him revolutionary food. The second day they gave him nothing. But they began to treat him all right really and then he could communicate. He said, “Why do you rely on violence with an innocent victim like myself knowing nothing about your country, or your politics? I’ve just arrived here and violence doesn’t pay.” And they said, “Well, because the government won’t listen to us.” A lot of them were students also that were anti-government besides the ones who took Burke and some of them hadn’t even met their leaders. Like the Castros, there were lots of leaders in the mountains. They were just given orders…. So Burke spoke and said that these young people should be heard. And he kept his promise, and there has been very little terrorism since then.

Q: So they weren’t questioning him or anything?

ELBRICK: Yes, they questioned him all night long while he was bleeding because they bandaged his eyes as he got out of the car. They put a kerchief around his eyes and he pushed them away and pushed the thing off his eyes and he felt they were going to shoot him on the spot. He didn’t know what they were going to do, so he resisted which he shouldn’t have done. That’s when they beat him terribly on the head. So he was all night long being quizzed about nothing that he could answer. He knew nothing about the country.

But then in the end they dumped him on a mountain top and said, “Stay 15 minutes by your watch,”…they gave him back his watch. They washed his clothes but didn’t return his tie, and then they shook his hand.

But in any case Burke came back to the United States nine days after he was liberated and at his own expense brought me, had an appointment at the White House to see the Chief of State to give him the story direct. He went to the White House, he was led into the White House in the direction of the Oval Office, and then was told that the President was unavailable. Nixon. So Burke said, “I’m not going to anybody else. I was going to our President who appointed me.”

So he went back to Brazil and he stayed nine months feeling very, very sick because…he was horribly beaten, had 75 stitches taken in his head. And they were opening up the Foreign Office in Brasilia, Burke had to go to all those ceremonies in white tie and tails and so on, and he was feeling dizzy and faint and I remember he was hanging on to the car door and I thought, “My God, what’s the matter with this man?”

And this was a clot which had formed in his jugular vein which our Embassy doctor did not discover but he had stitched him up and said, he needed some rest and “…you’ll be all right.” This was causing the fainting spells. Then Burke appealed to the State Department that he should come home and have a medical examination and he had ten operations, one each year. They removed that thing which was the size of a Kennedy dollar from his jugular vein from the blow on his head.

There were nine other operations and the last two were his legs, removed from his hips. He lived for two years and then he got pneumonia and he died. He got a cold from one of his grandsons on Easter Sunday in Chevy Chase, where we had a family reunion and one of the little boys who went up and kissed his grandfather had a cold and Burke got the cold because he wasn’t too well so I suppose could catch colds more easily than the normal person….

“Goodbye, Mr. Watergate”

Q: Did the President ever see him?

ELBRICK: No, but I got even with Nixon about three weeks ago. I’d been lying in wait like a three-headed serpent and a six-pronged tongue viper. I saw him at Loy Henderson’s funeral…we knew Loy fairly well and I went because Burke was devoted to him and I wanted to go. Somebody poked me and said, “There’s Nixon standing at the foot of the church steps,” a little church on Sixteenth Street, a Methodist Church.

So I went up to him and I said, “How do you do, Mr. President?” And he said, “How do you do,” and smiled from one ear lobe to the other. And I said, “And how is Mrs. Nixon?” and he said, “Fine,” “…and, the children?” and so on, just a very quick little conversation.

And then I said, “Do you happen to recall a man by the name of Burke Elbrick?” And he said, “Oh, yes. I appointed him as Ambassador to Brazil.”

And I said, “Do you remember that he was kidnapped down there and that you were his Judas and his Pontius Pilate?” And I said, “Goodbye, Mr. Watergate,” and walked away. And that was the end of that. Of course, he probably never would even remember the scratch I gave him but at least I felt good for it….