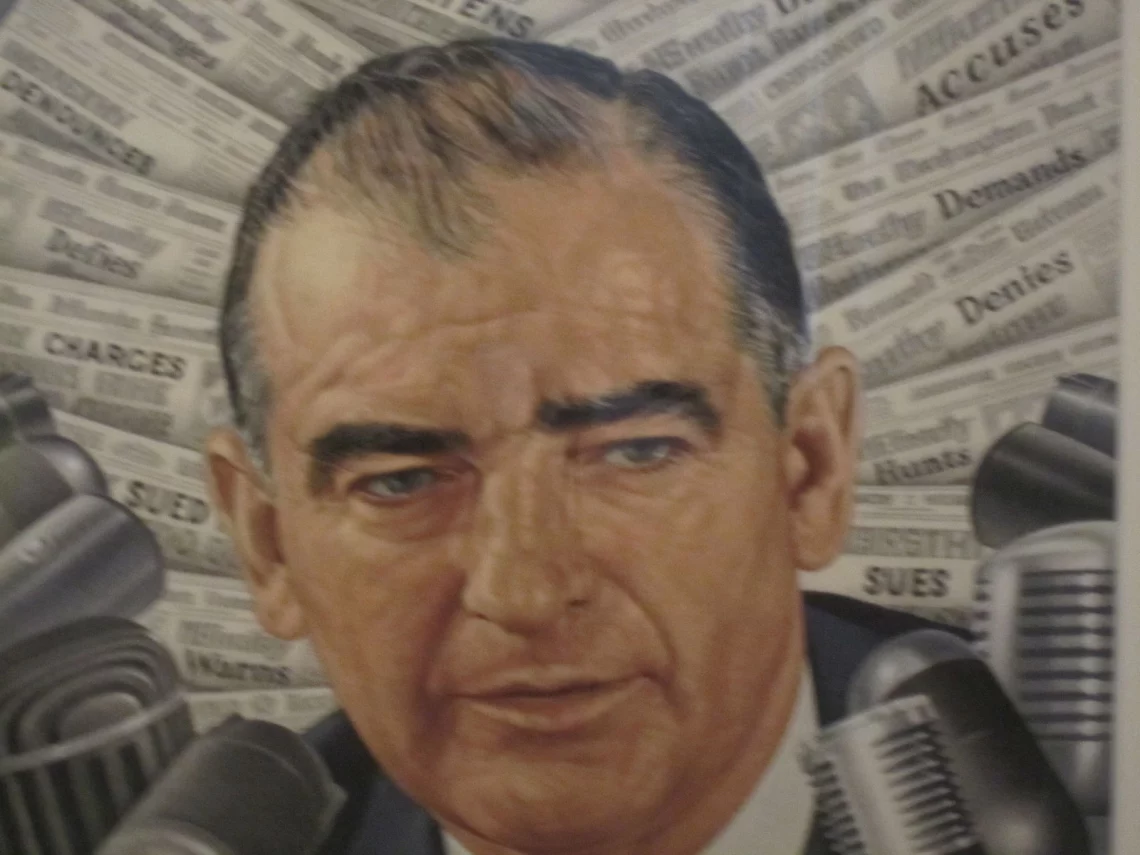

With his infamous Wheeling, West Virginia speech on February 9, 1950, in which he declared he had a list of communists working in the State Department, Senator Joseph McCarthy ushered in one of the darker periods in the post-war era.

The speech came at a time when the fear of communism and communist infiltrators in American society was at an all time high, exacerbated by alarming developments like the “loss of China” to communism and the successful detonation of an atomic bomb by the Soviet Union. The case of Alger Hiss, accused of spying for the Soviets while working for the State Department, made McCarthy’s allegations plausible. This environment enabled McCarthy to spearhead the movement to investigate suspected communist dissidents within the State Department and elsewhere.

Often, he relied on colorful rhetoric to make up for a lack of evidence. His tactics contributed to creating an atmosphere of fear and intimidation throughout the Department. A number of people were unjustly accused and were either forced out or suffered lasting damage to their reputations. One such person was Vladimir I. Toumanoff. He was not one of McCarthy’s more well-known targets like the so-called “China Hands,” but his story serves as a compelling example.

He came under scrutiny because of his Russian background, despite having grown up in the United States with tsarist parents. McCarthy attempted to paint him as disloyal and a Communist sympathizer and it was only some shrewd outmaneuvering that saved Toumanoff’s career. He went on to enjoy a fruitful and memorable career in the Foreign Service, being in the thick of notable events in diplomatic history such as the U-2 incident and the trial of Francis Gary Powers. Vladimir I. Toumanoff was interviewed by William D. Morgan in 1999. He discusses his experiences with McCarthy which occurred from late January to early February in 1953.

You can read other Moments on McCarthyism and on Russia and the USSR.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“It must be like being interrogated by the KGB”

TOUMANOFF: So it was when on an otherwise routine day in late January 1953 – the 28th, I think – the telephone rang in my office and a peremptory voice commanded me to appear that same afternoon at a room in the Senate Office Building. When I hesitated to reply, the voice said it was calling from the Senate Government Operations Committee (Sen. Joseph McCarthy, Chairman) and repeated the order.

I demurred, saying I would need to check with my superiors. The voice said it did not care whom I checked with but unless I came it would immediately issue a subpoena and send U.S. Marshals for me.

So I said that would not be necessary and I would be there, with which the voice hung up. I spoke with my superiors in Foreign Service Personnel [FP], as I recall including Ambassador Robert Woodward, a man of great integrity and then Director of FP, and was told that there was a presidential directive that we should all cooperate with the Government Operations Committee and that I should go and cooperate. That was the beginning.

I was taken to a windowless room somewhere down in the basement of the Capitol building, and was confronted by the three Committee staff who were to be my interrogators: Roy M. Cohn, Julian G. Sourwine and G. David Schine. I was sworn, told that our meetings would be in “executive session,” and that if I told anyone of what transpired I would be in contempt of the Senate and face jail. In this first interrogation, while suspicious, they were not overtly hostile as they established my identity and asked about my own and my family’s history.

At the end I was ordered to return the next morning. My recollection is that for the next four or five days, morning and afternoon, I was interrogated, sometimes by all three, mostly by two in rotation, sometimes by one at a time. They concentrated in ever greater detail on my parents’ and my own history, were repetitive as though they hadn’t heard me before or were seeking and prompting differing versions or contradictions. Sometimes they were mild, sometimes hostile and sarcastic, or played good and bad cop.

Their pressure was intense and exhausting, especially when they plainly demonstrated that they thought I was lying under oath. Their behavior was unpredictable from moment to moment, and their questioning was contradictory, leading, and calculated to confuse and entrap. I came to think that, with the exception of physical abuse, it must be like being interrogated by the KGB. To find that happening to me in the U.S. Capitol building was in itself shocking and terrifying, which I suppose was the intention.

Several things became clear to me in the course of those days: They were not interested in me as an individual, nor in the factual accuracy of my testimony. Facts and testimony could be twisted or disregarded. I was not their true target. I was just an exploitable and expendable instrument if I and my story could be bent to serve their purposes….(Toumanoff at right)

A few parts of my testimony in these “Executive Sessions” came to have a bearing later on the course of my public hearing before the Committee. …I explained to the interrogators: That the Russian Embassy in Constantinople, on the grounds of which I was born, was Tsarist, not Soviet, at the time; as well as my father’s history as a White Russian Imperial Guards Officer fighting against the Reds in the civil war. That I had applied for and received citizenship as soon as I was legally able. That I had volunteered for military service and been medically turned down.

And, in what turned out to be critical, that the Department had two separate sets of files on all personnel, one in the Bureau of Personnel for administrative materials — CV’s, assignments, promotions, efficiency and inspectors’ reports etc. — and another, separate and classified, in the Bureau of Security.

I was asked what would happen if, in the review of files for the Selection Boards, derogatory security information were found. I replied that it would promptly be sent to the Security Bureau for investigation. Asked if it would be sent to the Selection Boards, I replied that it would not as they had no power to conduct investigations, such investigation by that Bureau should be undertaken without delay, and that all the Selection Boards’ recommendations for promotion would be sent to the Security Bureau for clearance before any promotion action could be taken. Did I think that a good idea? Yes.

“‘Mr. Toumanoff’s testimony will be as follows’”

What I did not know at the time was that McCarthy had just established in sworn public testimony by Ms. Balog [Helen B. Balog, supervisor of the Foreign Service file room] that much material was missing from the personnel files under her charge, and that some derogatory documents had been removed by orders from above against her protests, and even whole files were missing of people she thought suspect. Further, she had named me as having access to her files, although she evidently did not accuse me outright of such removal.

At the end of the last day (a Friday) in “Executive Session” they ordered me to appear before the Committee for a Public Hearing on the following Monday morning. Then they held up a sheet of paper for me to read, which they would not let me touch, the heading on which was “Mr. Toumanoff’s testimony will be as follows.”

What it amounted to was that my parents were Russian and my father had never applied for American citizenship; that I was born in a Russian embassy years after Russia was Soviet; that I had not applied for U.S. citizenship until I decided to join the Foreign Service; and that I had not served in the U.S. armed forces. As I recall, during World War II aliens could refuse to serve.

Not only that. What I also did not know was that McCarthy had announced at the end of Ms. Balog’s testimony that Toumanoff was born in a “Russian legation subsequent to the Communist revolution, so of necessity his parents had to be acceptable to the Communist regime,” and that I would appear to testify the next day.

They showed me one page [of the testimony]. And I recognized immediately that in the first place it was inaccurate, it was not only inaccurate, it falsified the family history and myself. But were I to challenge that piece of paper immediately I would never get a chance to challenge it in public, because McCarthy would simply make some announcement on the floor of the Senate describing me in those terms with the obvious conclusion that I was a Communist, or Communist sympathizer, and an agent recruiting and helping promote more spies.

The big lie would gallop around the world, and the truth, if ever made public would never catch up. So I avoided agreeing that such would be my testimony by pointing out some misspellings and mistaken dates and let it go at that. They thought I did not realize the import of what I was reading, and I calculated that I could set the record straight in the Public Hearing. Before the Committee, with Senator McCarthy in the Chairman’s seat.

Q: He considered you important enough to give you his time.

TOUMANOFF: Well, obviously they thought they had a wonderful story proving that the Department of State was riddled with Communist agents, myself in particular. In the meantime, I had recognized, somewhere along about the middle of the interrogation, that their interest was not really in me as an individual. They couldn’t care less about the truth about me or the accuracy of their statements. They were interested only in making another public sensation. Had I any doubts on that score, that piece of paper was proof positive.

Q: Had you consciously been forced to give names of other people?

TOUMANOFF: No, not in Executive Sessions. I think they felt they could twist and turn my story sufficiently for their purposes so that they wouldn’t need any names. That could be saved for more sensations later.

However, in the Public Hearing McCarthy threw names about in allegations of improper influence and destruction of damaging documents about suspect employees. The names and allegations were reported in the press, but never authenticated. Those of the allegations which I was charged to verify proved groundless or simply false, and I so reported to the Committee in writing after the hearing. But, needless to say, none of my report ever surfaced in public.

Persona non grata in the State Department

Q: They already had the names they needed.

TOUMANOFF: There was another clear implication — that I had joined the Foreign Service in order to recruit my friends, Communists and spies, and then I had gotten myself assigned to the promotion system so that I could get them promoted. So here was this wonderful fabrication they had created which they could document with what I would call factoids.

In the meantime I had concluded that, as I say, they were not interested in me; they were interested ultimately in an attack on the Secretary of State and on the President. So I went back to the Department to explain what was happening, and I ran into a stone wall.

As I walked into people’s offices, they turned pale and figuratively they adopted the pattern of the wallpaper and disappeared. Any association with me was damning in their eyes — too dangerous and too terrifying.

Q: And all the way up to the Secretary of State.

TOUMANOFF: Well, I didn’t get anything like that far, but after going up about three echelons or so, I realized that I was persona non grata in the Department of State, and that I was not going to establish communication or get any help, really, of any kind at all. I was on my own.

Early on I did get some [help]. I had always assumed that the embassy in Constantinople was still Tsarist when I was born. So, early in the interrogation, I went to the Department’s Historian, and, without explaining why I was asking, asked him what was the status of the Russian Embassy in Constantinople on April 11, 1923.

And he quickly told me that the Soviet Embassy was in Ankara, some 200 miles away, that the Constantinople mission was still the old Tsarist Embassy, just as I had assumed, and it did not become Soviet property until after the British evacuated, some months, sometime later, after September when my family left Constantinople. That was really the only assistance that I got within the Department.

Q: You were only one, obviously, of a number of people, employees, that they faced, scared, obviously with reason.

TOUMANOFF: Especially with this order from the White House to cooperate with the Committee….

But this was early 1953 and I don’t know whether this was [Eisenhower’s] order or one left over from some previous Administration.…

It was a terrifying experience. Part of the terror was that if you grow up in the United States and you go to school in the United States and you read American history and you admire the country, you are not only mystified but totally taken aback to experience something as bizarre and as corrupted and as vicious as this, in the United States Senate. You’re utterly unprepared.

This is not the country that you know. The terror was magnified by finding that the Department — senior officials of the Department — were equally terrified, perhaps not equally, but certainly were frightened enough to avoid contact with you, that in their eyes somehow you had already not only been condemned, but that anybody who associated with you was likely to be equally condemned….

“My wife received threatening and obscene phone calls”

I was aware of the fact that some people had been attacked by McCarthy — not a great many at that point — and I was perfectly conscious of his accusations made very publicly and on the floor of the Senate about the State Department being riddled with spies and so forth, but I had no conception of the viciousness of the interrogation.

Q: Worse than the KGB.

TOUMANOFF: Well, the discomfort was considerable. Not only that, but when I came home, because there had been some publicity about me leaked from the Committee – purposely, to prepare the ground for this hearing, where there would be this great revelation, that “We’ve got one!” you know, that we’ve captured one, there he is, we’ve identified him.

Q: You didn’t lose China.

TOUMANOFF: But it was worse. I was obviously spying for the Soviet Government at a time when the Cold War was very, very bitter. When I got home, I found that my wife, with our infant son and pregnant with our daughter, had already been receiving threatening, abusive and obscene telephone calls from anonymous voices. So altogether this was a trying time.

But there I was, Friday afternoon, and I had been reminded by the Committee staff, Cohn, Sourwine, or Schine, that these interrogations were Executive Sessions of the Committee, and that if I told anyone about what had transpired, I would be found in contempt of the Senate and jailed. So that was the situation as of Friday afternoon.

It was all pretty overpowering, and I wasn’t getting much sleep. Anyway, I decided that I would disregard that injunction for silence and that I would be protected if I spoke with a lawyer as a client.

Q: Were you advised of that at any point, even by some of the timid ones?

TOUMANOFF: No. Oh, certainly not. No one was reading the Miranda Act to me. Besides, they probably didn’t know about McCarthy’s gag practices.

Q: Well, maybe it didn’t exist, but at least good counsel would have been good advice.

TOUMANOFF: Quite the contrary – I was under injunction not to speak to anybody. And they didn’t make any exception for lawyers. So I asked my wife if she knew, or if the family had, any lawyers who could – I had not told her any details, they were too ugly, and the phone calls were already distressing. But that wasn’t the question. I just didn’t happen to know any lawyers in town.

Well, it turned out that an uncle by marriage was Samuel Spencer, who — and this is a side issue which really is kind of pertinent to the whole political scene in Washington at the time — was the senior partner of a law firm here in Washington, and the papers for his appointment by the President to be Chairman of the District Committee, which was the governing body for the District of Columbia in those days, were on the President’s desk for signature.

Sam Spencer knew this. I didn’t….Knowing nothing of this, as a family member he seemed to me the right person to consult.

Q: Good political connections, in any event.

TOUMANOFF: And a very good reputation. I called to ask if I could see him before Monday, and told him what the problem was. Without hesitation he asked me to come in first thing Saturday morning. So I did, and went over the whole business with him. In conclusion he said, “Vlad, I know that what they are about to announce or try to prove at this hearing is simply false, but I don’t know all the details. Could you write down the truth on every one of these points?”

[I told him] simply the facts about myself and family. How it was that I happened to be born in the Tsarist Embassy, not the Soviet Embassy; that my father was a titled officer in the Imperial Guard and had fought on the sides of the White armies against the Bolsheviks; that I had volunteered for U.S. military service; the reason I hadn’t gotten my citizenship until I was old enough to do so, and applied the day after I turned 21 years old, and so forth.

[Lay out the facts] and to repudiate, or attempt to repudiate, their appalling collection of factoids. I said, yes, I certainly could do that, did so on Saturday evening, and I went over it the next morning with Mr. Spencer.

He then said, “Vlad, I’ll go up to this hearing with you and sit beside you and represent you before the Committee.”

Q: You could get representation-

TOUMANOFF: I didn’t know that, but he did. I thanked him, but said I didn’t think that would be necessary. My story is perfectly straight forward, and all I wanted to do was point out the truth, and if it happened to contradict something the Senator or the Staff said I’d not hesitate to correct it. At which Sam Spencer said, “Well, Vlad, you probably will need some counsel, because you don’t know what you’re up against, so I will be sitting in the front bench of the audience right behind you, and the moment you think you need some help, just ask me, and I’ll come forward and sit down with you and explain that I’m representing you.” The next day he was there.

Had I turned to him, had I accepted his offer to represent me, he never would have been appointed to the Chairmanship of the District Commission, the equivalent of Mayor of the Nation’s Capital. He knew that, but never told me. I only learned of it much later.

But the integrity of that man was such that he was prepared to make that sacrifice on principle. A yawning chasm of contrast with Senator McCarthy and his jackals. There are people of such integrity that one is left after the entire experience not in despair, but lost in admiration for the country.

That afternoon, which was Sunday, February 5, I think, 1953, I was walking around in Rock Creek Park trying to clear my head for the next day’s hearing when coming the other way was a friend and college classmate called Douglass Cater. Doug Cater at that time was the Washington correspondent for The Reporter magazine.

We hadn’t seen each other since college days, and Doug asked, “How are you?” To my own surprise, I told him; everything. It turned out later, of course, that the threat of contempt was hollow. No one was going to go through the trouble of getting the Senate to vote me in contempt. Doug asked if I had my statement on paper and I showed it to him.

“Well,” he said, “make about 50 copies, and I will come to the Committee Hearing room in advance, and I will introduce you to the entire press corps, and as I introduce you, you hand out copies of this statement to every one of them.”…

I did, and he did. And McCarthy and his staff were sitting up there because they’d been hearing some other witness before me, probably laying the groundwork for my appearance, and they watched us, with the floodlights glowing, flashes popping, cameras grinding, all going on as I went around from correspondent to correspondent being introduced, shaking hands and handing them each my paper.

I was called to the witness table, sworn in, and McCarthy looked down at me, irritated, and suspicious…. [He was] with his staff which must have assured him that my testimony would be as they had written and shown it to me. He opened with “I understand you have some sort of a statement.”

I said, “Yes, sir.”

He scolded me for disobeying a Committee rule which stipulated that no statement would be allowed unless submitted to the Committee in writing 24 hours in advance. I replied that no one had told me about the rule.

He said, “Well, do you want to read it?”

I said, “Only if you want me to, Sir,” which was a mistake. I shouldn’t have been so cocky because I had put him on the spot. He didn’t know what was in it, the press had it and was reading it, and he didn’t know how to proceed with what he knew were falsities and distortions. I was rubbing it in.

His rejoinder was, “Read it!” A command, in a very angry voice. So I read it, and he knew that his whole fable about my parents’ communism, including his earlier public statement about my birth in the embassy, would be known to be false.

It was maybe a couple of pages long. And by the time I got through to the end of it, he realized, and so did everybody up there on the Committee, that Mr. Toumanoff’s testimony was not going to be according to that piece of paper that Cohn, Sourwine, and Schine had prepared.

It may have been passed around to the Committee members in preparation for the hearing. Most of the Senator Members were present….Then the hearing kind of fell apart. We sparred back and forth….

“McCarthy Catches a Red Herring”

The story that McCarthy was prepared to present to the press was destroyed….He couldn’t distort things the way he intended to. But he nevertheless tried to salvage some implication of communism with his questions, without much success. He asked, finally, why my mother had left her employment at the School for Advanced International Studies (she was Chair of the Languages Department).

My reply, “She died, Sir” so flustered him that he hastened to explain that although the School was being investigated for communist sympathies at the time, it was later entirely cleared.

And so he shifted to questions about my work in recruitment and promotion. Here he made more progress, rehashing Mrs. Balog’s earlier testimony about suspect missing documents and files, which I was in no position to explain except the I had found some that were simply misfiled.

It was an exhausting process because it was about as hostile, the questioning in this hearing, as you can possibly imagine. It was a constant, skillful attack to entrap me in an inconsistency, a contradiction of some statement of mine in Executive Session, distortions, rewordings of my answers with changed content, assumed false conclusions, imputed meanings and motives, impatient interruptions, long convoluted statements with which I was presumed to agree. I began to understand about the subjects of the Inquisition.

I held up for a couple of hours but eventually tired, and McCarthy sensed it. Referring to my testimony in Executive Session he suddenly asked, “Do you still think it a good idea to deny the Promotion Board the knowledge that a man they are considering for promotion is a homosexual?” Homosexuality had never been mentioned in Executive Session.

“May I elaborate?,” I asked, thinking to explain the two Bureaus, their separate files and the security investigation and clearance measures involved in the promotion process, all of which I had done several times in Executive Session.

“No, you may not,” he barked. “You can answer yes or no. You’ve already answered this question in Executive testimony. Just answer yes or no.”

I replied “Yes,” calculating that one of the other Senators would simply ask me why I thought so. None of them asked. The irrelevant question of “allegation” or “positive knowledge” arose. I said that if there were documents proving a man to be homosexual he would not be in the Foreign Service: he would have been fired.

To my amazement that brought a chorus of guffaws from the audience behind me. Senator Henry Jackson asked, “Suppose that files about to be presented to a promotion board showed that a candidate for promotion is a convicted homosexual and a certified copy of his conviction is in the file?”

The whole dialogue had become so unreal that I tried to think how to get it back to reality in the face of guffaws, and knowing McCarthy would cut me off, as he had so often already when I started an explanation he didn’t want.

He interjected “It’s a hard question to answer isn’t it?” I said “It certainly is,” and he banged the gavel adjourning the hearing, saying I’d have ample time later to reply. He then dismissed me commenting that I had wasted the Committee’s time. He had his press splash and, of course, I was never called again.

No one in the press asked me either. Most of the newspapers simply ran the story as it happened, leading with McCarthy’s sensation. One columnist, Jack Anderson of The Washington Post, if I am not mistaken, added his personal note that “lights glistened off my polished fingernails.” A few papers, evidently from their own knowledge, or perhaps prompted by friendly Senators, included a clarification about the security safeguards.

The Department of State issued the following statement, which missed the point. Instead of describing the security safeguards built into the promotion process and the difference between personnel and security files, the Statement elaborately repeated my assertion which had already drawn guffaws: “Since 1947 the Department has considered homosexuals and other sex deviates to be security risks. The Department, therefore, has pursued an inflexible policy that any employee found to be a homosexual or a sex deviate must be separated from employment immediately. Furthermore the Department has carried out, and continues to carry out an aggressive program to detect and rid itself of such employees.”

Q: Was McCarthy the sole inquisitor?

TOUMANOFF: Yes, for almost all of the hearing. A couple of other senators had a question or two but they didn’t change the conclusion. Everybody knew that the communist angle was a washout. As one headline put it, “McCarthy Catches a Red Herring.”