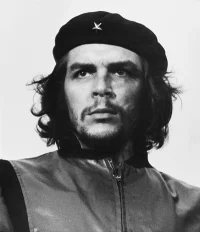

He is arguably the most well-known revolutionary in modern history and his now iconic photo can be seen on everything from t-shirts to coffee mugs. He has been the subject of many romanticized books and movies, which often gloss over the brutal methods he and others employed to achieve their objectives. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was a medical student who became radicalized by the poverty and injustice he saw in Latin America in the 1950s.

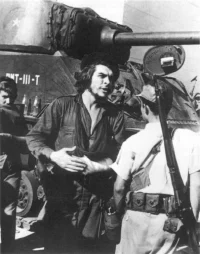

While living in Mexico City, he met Raul and Fidel Castro and sailed to Cuba aboard the yacht, Granma, to fight Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Guevara soon rose to prominence and was promoted to second-in-command, playing a pivotal role in the victorious two-year guerrilla campaign that deposed the Batista regime. Following the Cuban Revolution, Guevara performed a number of key roles in the new government, including major changes in the agricultural sector and reviewing the appeals and firing squads for those convicted as war criminals during the revolutionary tribunals.

He was also considered the chief architect behind enhanced ties with the USSR; however, he later grew angry with Khrushchev when he withdrew the nuclear missiles from Cuba and later said the cause of socialist liberation against global “imperialist aggression” would ultimately have been worth the possibility of “millions of atomic war victims.” His increasing radicalization towards Maoist-style communism led to tensions with the Castros and their relations with Moscow. Guevara then tried to foment international revolution in Algeria and the Congo before heading for Bolivia.

In the summer of 1966, Ambassador Douglas Henderson at Embassy La Paz received intelligence about the planning of a guerrilla uprising to overthrow Bolivian President René Barrientos’ administration. Two members of the militant group were detained and interrogated when they were caught trying to sell their weapons in Camiri, a town just outside of the dry jungle in the Andes. It was then discovered that Guevara was the leader of this group.

This is the story of how the famed revolutionary met his end on October 9, 1967 at age 39. Ambassador Henderson served in Bolivia from 1963-1968; he was interviewed beginning in April 1988 by Richard Nethercut.

Rumors of Guevara’s Presence in Southern Bolivia

HENDERSON: The first word that we had of anything like the Guevara episode must have been in the summer of 1966. In Bolivia the problem is not one of gathering information, but of sorting it out. You have a lot of rumors fed into the embassy all the time, and they may point like magnets under a scattering influence, they point in all directions. But if suddenly all the arrows point in one direction, you start to take them seriously. At first we didn’t get very much out of this. There was a story that there was a guerrilla uprising being developed in some part of Bolivia, it was kind of vague. In the southeast, they said, a man by the name of Guevara — well, there are lots of Guevaras in Bolivia and a number of them are known revolutionaries of one kind or another….

I think it’s important to notice that this Guevara episode was one that was carefully planned. It was not a hit-or-miss operation, although it may have on the surface appeared to be.

In the first place, the selection of Bolivia, and the selection of the site in Bolivia, must raise questions. If Guevara had chosen the Amazon rain forest river system, no one would have been particularly surprised. That river system had been a communication channel for communist couriers going between Cuba, Brazil, Peru and other countries for a number of years. When I was stationed in Peru we knew that some of the Peruvian guerrilla operations were being sustained this way. But he didn’t choose that. We also found out later that, for example, the Frenchman Régis Debray had surveyed the Bolivian scene earlier, possibly as early as 1965.

And so you have to stop and think, why? Now it’s also obvious that there had been a number of other interested parties in this operation. The girl, Tania [Haydee Tamara Bunke Bider, Argentine-born East German who was Guevara’s primary agent in La Paz], appears to have been attached (for what purpose I have never investigated) to the Guevara operation. There also was an Argentine who was attached to the operation from Argentina….

I would have to say that I think Guevara’s ultimate objective was to establish a revolutionary base in Bolivia from which he could move into northern Argentina, he being himself an Argentinean.

This is the significance because otherwise the area itself would not be a convenient base to start a revolution in Bolivia. The way to do that would have been to go into the mines. It wouldn’t have been hard to start up all kinds of difficulties in the mines. If you had wanted to just facilitate communist operations in surrounding countries, an Amazon River base would have been a dandy place to be; very easy place to move around, in and out.

He was in a part of Bolivia called the dry jungle. The Andean mountain chain faces out to the Chaco [ecosystem], and it is very precipitous, very broken up, and lots of ravines and channels and gullies, and very difficult both for movement, and also because of the living conditions. All the diseases known to mankind are endemic in that particular area….The only significant industrial resource in the area is the oil fields at Camiri, and yet there was never any evidence that that was an objective.

The other part of it that seems to indicate that this was a well thought out, well established operation, was that when Guevara failed there were a group of Cubans who were with him, about six I believe, who had been surrounded in the same area. They escaped from the Bolivian army and disappeared, and resurfaced about four months later crossing the high Bolivian plateau in a very remote, desolate area fronting on Chile, a place called Uyuni. They escaped across the Chilean frontier, and the Chileans shipped them back to Cuba. But my point is rather that they were able to sustain themselves in Bolivia as hideaways for months. They could only have done that with some sort of a support group.…

Blown Cover

Q: Mao’s dictum is that the guerrilla should swim in the sea of the people, and it did seem that this was very foreign territory for Guevara. They’re a Quechua-speaking population, are they not? Did he have support in the area?

HENDERSON: The first tip-off to his actual presence was that two Bolivians, completely fed up with the discipline of his camp, left the camp, fled to Camiri with some arms — I don’t know just what they were —and tried to sell their arms there in Camiri. They were promptly picked up by the local military commander and interrogated. The problem apparently in that camp was that the Bolivian recruits were treated with contempt by the Cuban hardcore, and were more or less the gofers.

Q: Did he get any significant support from the population?

HENDERSON: There is no significant population in the area. This is, as I say, dry jungle, very little in the way of local population there at all; very scattered subsistence farms, nothing in the way of population concentrations.…

Guevara intended to harden his core group [of about 40 people] through training before he made any move. He was off on a training march when the two Bolivians broke away and went down to Camiri, and the whole thing was blown. Before Guevara got back, the local Bolivian commander decided that he was going to be a hero and sent I guess maybe a squad, maybe a little bit more, of his soldiers into the area where the Bolivians had told him the camp was located. But they were very clumsy and fell into an ambush….I guess a couple of them were killed, the rest of them were captured, brought into camp, interrogated, and I guess their shoes were taken because shoes were a very valuable commodity in this terrain, and then they were sent back. When Guevara came back, in this time sequence, he realized that his cover was blown, and decided he had to break camp and move out….

By this time it must have been March of ’67. Now, there were two things going on in parallel so I’m going to follow one and then I’ll follow the other.…

Guevara broke camp, decided that neither Debray nor the Argentinean could handle forced marches in that terrain. He moved his group south for about a half a day’s march to where he could shake those two out and drop them off, and then he turned back north. So Régis Debray and the Argentinean were captured almost that same afternoon and tried to give a story that they were just newspaper reporters; the Argentine was a journalist, but also a member of the Argentine Communist Party.

Debray said he was a French journalist, and he was. But the Bolivians didn’t necessarily believe them, and held them and started interrogating them. Régis Debray, of course, being a French intellectual and his mother being a person very close to Charles de Gaulle, managed to get a lot of international publicity. It became a very sore point for the Bolivians.

René Barrientos [President of Bolivia, 1964-1969] called me the night that Debray had been captured. He didn’t know who Debray was, but said that they grabbed this guy, part of this guerrilla uprising. And I said, “Your Excellency, what are you going to do?” He said, “Execute him.” I said, “Really, I think that’s not quite on. I’m not here to tell you what to do, but I can tell you what the consequences are of an action like that.” And for several days my military personnel were telling me that the man was dead.…

But the Bolivians kept Debray alive, and they kept the Argentine alive. But they got all kinds of bad publicity out of imprisoning this French intellectual. Mrs. Debray came to Bolivia and almost became a public relations problem for the French embassy, as much as anything. But, in any case, Debray is alive….As a matter of fact he [was] one of François Mitterand’s [President of France 1981-1995] advisers….

Caught by Surprise

As I say, there was another ambush and later on, probably about the middle of August [1967]. A Bolivian military group which were not part of the rangers, but which were operating in the general area, stumbled on Guevara’s bivouac at night and caught them by surprise. There was a kind of Chinese fire drill, everybody scrambling, nobody knowing what was going on. The Cuban group melted into the jungle. The Bolivians grabbed everything in sight, and it turned out that they’d picked up Guevara’s diary, his code books, his passport, his forged passport, the whole bit.…

We sent the documents back to Washington, but Washington said, “Oh, we don’t want to touch that stuff. Turn it over to the Bolivian government, and let the Bolivian embassy bring it in and they can present it to the OAS [Organization of the American States] and not as U.S. documentation at all,” which was done.…

This did establish that it was indeed Guevara. Now it’s interesting to go back just a second. In May of that year I was in Washington on consultation and I went over to talk with Fitzgerald in CIA, who was fairly high up, and he said, “Look, this can’t be Che Guevara. We think that Che Guevara was killed in the Dominican problem and is buried in an unmarked grave. But we could think of nothing better than if Che Guevara were to be in command of this operation because he is the worst guerrilla operative that we could be up against.”…

There was a real doubt in our intelligence community’s mind as to whether this was Guevara, and now we had the proof that it was indeed Guevara. So now we’ve had episode one, the Bolivians discovering, telling, about the operation, disclosing that there was a camp; two, an encounter between the Guevara group and the Bolivian army, some losses. Guevara pulls out and starts on the long march, and the Bolivian military follow and they run into another ambush and this time they take significant losses, but Guevara by this time realizes he is being pursued. On the way, he splits his forces and leaves Tania with a group to be following up. Tania gets ambushed sometime in August, and is killed. The Bolivian army runs across Guevara’s bivouac and discovers the documents. We now know that it is Guevara.

There’s one small episode which doesn’t really mean anything. Guevara in late July surfaced in a small town between Cochabamba and Santa Cruz because he needed some medications — having asthma he needed medication. He went into this town, got whatever he needed, and left, but we now had him pretty well located, and the Bolivians now had their ranger battalion trained, and we had furnished them materiel.

But, because of my intervention to keep Debray alive, and the subsequent bad publicity which the Bolivians had gotten out of the whole operation, the Bolivian military were not very forthcoming in giving us any information.

So on a Sunday morning in September…the Bolivian ranger battalion surrounded Guevara and his group. The Bolivians had the high ground. They were firing down into this ravine. They wounded Guevara and his bodyguard [Simeón Cuba Sarabia], and isolated them from the rest of the Guevara operation.

“Execute your Prisoners”

They took them prisoner, and took them into a place called La Higuera, meaning The Fig Tree, where the ranger battalion had their field headquarters. They radioed to the chief of staff through their headquarters in Santa Cruz back up to La Paz to the chief of staff, “We have Guevara, what should we do?”

And now I do not have the texts of these things, but I know what happened. The Bolivian high command sent an order to the general in Santa Cruz who relayed the order to the commander in La Higuera, “You are to execute your prisoners.”

Guevara was executed about 1:00 in the afternoon. His bodyguard had been executed before him. Then for some reason the Bolivians decided to put on a media show. They transported Guevara’s body to another small town the following day and brought in all kinds of media. The New York Times was represented. There was a lot of international reportage going on.…

The Bolivians saw it as an opportunity to have some luster added to the Bolivian reputation. They felt that they had struck a blow against communism, and communist infiltration, and that we should be grateful. But after Guevara lost his base camp — even though the Bolivian army did get a bloody nose in the second ambush. After that they felt pretty confident that they were going to be able to handle it. They were particularly confident because of the training that the ranger battalion got.…

Final Thoughts

HENDERSON: There is one other thing that I’ve never really understood….One: Guevara’s diary. The Bolivians tried to put it up for auction, couldn’t get the money for it that they thought they ought to get, it suddenly went underground and reappeared in Fidel Castro’s hands. It’s just an interesting little episode but who in Bolivia was negotiating with Fidel Castro for the diary, and so on. That is one of those peculiar threads, just like how those six Cubans managed to escape from Bolivia.

And the other thing is, that a number of prominent Bolivian army officers have been assassinated. One of them was the general in command of the area who transmitted the order to execute Guevara and he was gunned down in Paris.

The chief of staff and probably Barrientos gave the order, but it had to be transmitted through the area commander in Santa Cruz, and that man’s name was General Zenteno. He was assassinated in Paris [in May 1976 while serving as Bolivia’s Ambassador to France by members of the “Che Guevara International Brigade”; the gunmen were never caught] and nobody has really explained to me what happened. There was another general who was assassinated in Argentina in about this same time sequence….

Apparently, according to whatever sources, however reliable they are, when Guevara was taken prisoner (he was wounded, he had a wound in his leg), he apparently said, “Don’t shoot me, I’m Che Guevara. I’m worth more to you alive than dead.” Now this may be apocryphal, I don’t know, but that is what is reported to have been said. The fact is he would have been worth more alive than dead, but I think there the Debray syndrome kicked in and the Bolivians were just not having any more of that.

My question Is why is this thug, murderer, sadist considered a hero? Even Castro excommunicated him from Cuba. He did not approve of the Che way. His goal was revolutionary. There was nothing but ideology in his head with no real purpose to anything period. Young people have a delusionary portrait of this pond scum. He was a monster. Nothing holy about his concept on life. Holding this chimp up to the world as a hero is a disservice to the facts.

Che Guevara did not die from the gun shots, he was still alive and the soldiers were told to have him stabbed in the neck, with a ballonet.