May 9th, 1994 marked one of the most significant – and previously unimaginable – milestones in modern African history as Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as President of South Africa. A key figure in the African National Congress (ANC) since the early 1950’s, Mandela was repeatedly arrested for seditious activities. Although initially committed to non-violent protest, he co-founded, with the South African Communist Party, the militant Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”) in 1961, leading a sabotage campaign against the apartheid government. In 1962, he was arrested, convicted of conspiracy to overthrow the state, and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was imprisoned for 27 years, primarily at Robben Island. He was locked in solitary confinement on several occasions and was permitted one visit and one heavily censored letter every six months. He was finally freed in 1990. Shortly thereafter, he and President F.W. de Klerk began negotiations on a new constitution to abolish apartheid and establish multiracial elections. In 1994, he led the ANC to victory and became South Africa’s first black president.

Princeton Lyman was the ambassador during this critical juncture and tells of U.S. support for the negotiations and subsequent elections, the concern regarding a possible right-wing coup, and Mandela’s warm regards for George H.W. Bush and his initially frosty relations with President Clinton. Lyman was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in May 1999.

Go here to read about the 1976 Soweto Uprising and other Moments on Africa.

The Beginning of Compromise

LYMAN: In 1989, F.W. de Klerk took over the government. In early 1990, de Klerk surprised everyone by legitimizing the ANC and the Communist Party, whose leaders mostly were in exile or in prison or underground. There had been tremendous turmoil in South Africa in the 1980s. A state of emergency had been declared; there had been large and sometime violent demonstrations with many casualties. Most people thought that the unrest would only be ended by a bloody civil war.

De Klerk surprised everybody by his very radical approach. He allowed all the opposition parties to operate in the open; he let Mandela out of prison. A way was found to allow the exiles to return. In 1991, a formal negotiation was begun to develop a transition process.…

When I arrived, the negotiations were in total disarray. The threat of more violence was palpable. No one knew where the country was heading. There was an interesting aspect to all of this….During the summer of 1982, [Vice President] George Bush wrote to both de Klerk and Mandela volunteering the services of Secretary James Baker who, President [Reagan] said, had just led a successful mediation effort in the Middle East after the Gulf War. Baker was prepared to assist the two South African parties to resolve their differences. Before leaving Washington, I was briefed on this idea and I knew that the administration was really anxious to be involved in South Africa.

But both Mandela and de Klerk declined the offer with thanks. They felt that the negotiations in South Africa were their problem which they wanted to resolve on their own. They both thought the U.S. could be helpful, but not as a mediator.…

Mandela and de Klerk finally met towards the end of 1992. They came to an agreement which changed the direction of the negotiations. First of all, de Klerk agreed that Mandela and the ANC would be the principal party in the negotiations – i.e. that [Mangosuthu] Buthelezi [at right] and his Inkatha party [which broke off from the ANC in 1979] would be a secondary party to the negotiations. Furthermore, de Klerk and Mandela agreed that instances of violence would not be allowed to interfere with negotiations. That was a key element in moving the process forward.…

The climax came in the spring of 1994. We were getting very close to an election. The government and the ANC had agreed to an election; they had agreed on a new constitution and on all other issues. But Buthelezi continued his role as a spoiler. He said he would not agree to any of the resolutions reached by the government and the ANC. His stance threatened to turn into a civil war in his province.

I had a large Congressional delegation visiting South Africa in May 1994. I was scheduled to speak at the Durban Chamber of Commerce. So I took the whole delegation with me and they listened to my speech. Buthelezi was also on the dais. My theme was that it was time for all parties to come together and prepare for the election. It was a very dramatic address. I got a standing ovation from a largely white business crowd. Buthelezi was furious with comments. He told the Congressional delegation that they had been brain-washed by the American ambassador. On the other hand, Mandela quoted my speech over and over again….

Providing Support

I need to talk a little bit about how we used our resources in our efforts to assist the South African parties to reach agreement. This was an important aspect of our efforts. We had a very flexible AID [Agency for International Development] program. When I arrived, all the aid flowed through non-governmental institutions at Congress’ insistence. Many of these NGOs were white-led, raising a lot of resentment in black community. I had an AID director who understood the situation; he developed procedures that shifted the emphasis and provided assistance to black NGOs. These were the people who would have key roles in the government after the 1994 elections. We funded a lot of conflict resolution processes around the country; that was our way of trying to keep the violence from exploding.

We put more than $25 million into the election – voter education, etc. We used the National Democratic Institute, the International Republican Institute, as well as others as our contractors. We supported South African election monitors as well as American ones. We provided experts on every issue that was being negotiated – freedom of speech, federalism, etc.

We were not at the negotiating table, but we certainly were all around it. We provided ideas; we supported an exchange program for the experts. We thus enriched the dialogue as did the Europeans who were also involved in providing this kind of assistance. We were not the only American institution involved in this effort to smooth the negotiations; there were American foundations involved – many of them had been working in South Africa since the 1980s. When I talked to Arthur Chaskalson, now the President of the Constitutional Court, he reminded me that in the 1980s the South Africans had access, through the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, to the best brains in the U.S. When it came time to negotiate, the U.S. government was not needed at the table because the delegates had been preparing for this over a decade with the assistance of a lot of foreign brain power and they were ready to negotiate a constitution. I think experience is a good illustration of how American support for a political process can be most successful.…

Concern about the Right Wing

The [elections] finally were held in April. The sides had been negotiating for years; at the end of 1992, I made some public criticisms about the slow pace. In 1993, Chris Hani was assassinated; he was probably the second most popular ANC figure. He was the head of the Communist Party and very popular. When he died, we thought that South Africa would blow up. It was this event however that drove the ANC to demand a firm election date. Without such a date, the prediction was for a calamity. So the date was set as April 1994.

The government’s line was that it didn’t object to holding elections, but it wanted a full constitution in place between the elections and the time a new constitution was to be ratified. The ANC just wanted a transition document. De Klerk rejected that and demanded a full constitution. So 1993 was devoted to writing a new constitution. Once the election date was set, it became a very important date.

My argument with Buthelezi was over his desire to postpone that date; in my view, the process had dragged on long enough. The election passed much more peacefully than we had anticipated.

I should mention one other area where we played a significant role. One of the issues in the transition was whether the right wing, including the security forces, would support whatever arrangements might be agreed upon by the government and the ANC. Among this group was a retired general, Constand Viljoen. He was elevated to the leadership of the right wing. He was very popular as a former general and farmer. He was a hero to the right wing; he was an Afrikaner. He later admitted that he had flirted with the idea of a coup in conjunction with the military. We spent enormous amount of time with him. We asked the Pentagon to send us some savvy generals who might appeal to his professional soldier qualities. We talked to him about the dangers of a civil war. We sensed that he really cared about his country, unlike some other members of the right wing. He did agonize over what a civil war might do to South Africa. In the end, Mandela charmed him into saying that he would study the idea of a separate state for the Afrikaners—a proposition that was not viable under any circumstances.

One day, Viljoen called me and asked whether he could trust Mandela. Would he really come through? I assured him that Mandela could be trusted. So he made the decision to participate in the elections; that was a very critical decision. Just before the election, he was supposed to sign an agreement with the ANC; he called me on the phone to inform me that in his view the ANC was stalling and that he was being hoodwinked with potential catastrophic results. So I called Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s deputy and told him that the agreement had to be signed and very soon. I was called back and told that the agreement would be signed on Saturday. Viljoen asked whether I would co-sign as a witness. I told him that we had not done so for any of the previous agreements, but that in this case, I would serve as a witness. I was the only ambassador to show up for the ceremony.…

The 1994 Elections

We had an enormous number of election observers from the U.S. The UN came to help with the election and we worked well with them. We approached the “Lawyers Committee for Human Rights”, an American NGO. We asked that they appoint someone to coordinate the activities of all the election observers who were flooding the country—assigning them to districts, getting them to work with their South African counterparts. They took over that role with our financial assistance. They kept the Americans organized and deployed in an organized fashion. That Committee played a major role.

Support from Washington was very important. Mandela always called George Bush even after Mandela had been elected president and Bush was retired. Whenever Mandela came to the U.S., he would call on Bush. Mandela liked the personal touch that Bush had. Later on, Mandela became very close to President Clinton. [Secretary of Commerce] Ron Brown was very active in South Africa as was [Secretary of Health and Human Services] Donna Shalala who came out at critical times.

There was a major delegation from the U.S. for Oliver Tambo’s funeral. These visits were critical to our credibility. Oliver Tambo had been the leader of the ANC when Mandela was in jail. He was loved by many people, but had in effect been shunned by the U.S. for a very long time. He died in the spring of 1993. The Clinton administration made a decision – with which I did not agree at first – to put together a huge delegation for the funeral. It was the right decision and I had been wrong. Donna Shalala was chosen to head the delegation. What I didn’t realize at the time was that she had deep roots in South Africa because she made many contacts there when she was the President of the University of Wisconsin.

Jesse Jackson and many others came as part of the delegation. They had a profound effect on the ANC. It was viewed as a sign of the U.S.’s great interest in South Africa and its new leadership. Shalala gave a wonderful speech, even though she was sandwiched in between the PLO representative and the Cubans. She said that that could be the end of her political career! She was terrific. The U.S. delegation was given great respect; the whole delegation sat on the dais at the funeral. Jackson also gave a speech.

The ANC gave a reception that night and it was very clear that the U.S. delegation had made a profound impression. So that visit was very important to our efforts to build a relationship with the new government. It wiped out what ever bitter feelings there may have been for the vilification of the ANC that had been practiced in the U.S. for so many years.…

The election came out as people had anticipated. The ANC just missed getting the two-thirds of Parliament, which it needed to pass constitutional changes without allying itself to another party. That was just as well. They captured every province but two. I had told everyone that Buthelezi would be a factor; most people had dismissed him as a non-entity. In fact, he won his province.…

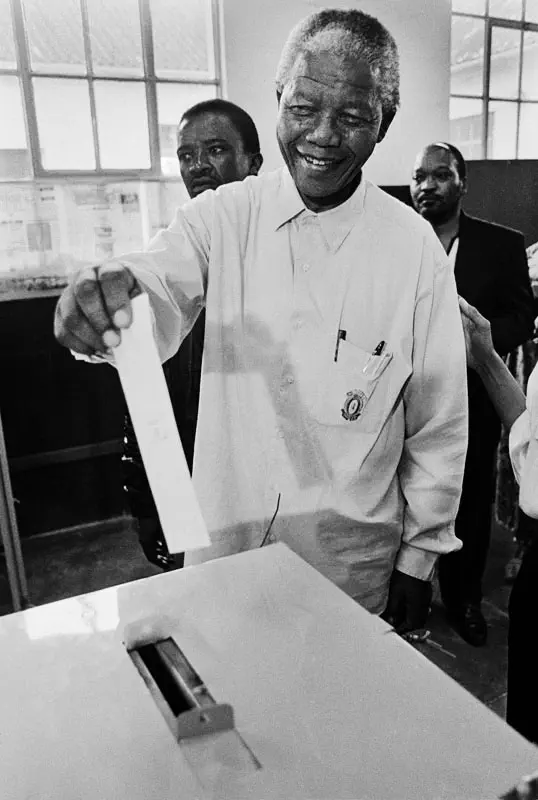

Mandela’s Inauguration

Mandela was inaugurated in May 1994 and I left South Africa at the end of 1995. The inauguration was magnificent. It was a wonderful affair. The election itself was touch and go. We didn’t know whether violence would break out. There were bombs exploded at the airport on the morning of the elections. The police arrested all the perpetrators, which was a good sign; there was no more violence that day. That gave us a clear signal that the security forces would abide by the results of the election.

As I said, the inauguration was magnificent. We were allotted ten seats; our delegation was 65 people – typical U.S. We had a Congressional delegation as well as one from the Administration which included Vice President Gore and his wife Tipper as well as the First Lady, Hillary Clinton. Unfortunately, the Secretary of State didn’t come. The highest ranking Department official who came was Dick Moose, the Under Secretary for Management.

[Secretary of State Warren] Christopher had always taken the position that as long as the transition process was moving along, he didn’t have to spend any time on it. He didn’t object to what was going on; he just didn’t spend any time on the issue. He only made one trip to South Africa and that was towards the end of his term. Mandela resented the neglect that the Secretary had indicated. The Department’s participation was very strange…. I know it gave us great support during the period leading up to the elections, but when it came time to celebrate a success, the Department did not show. Obviously, it was not important to Christopher to be seen at a celebration of a process that the U.S. had devoted so much attention. Mandela made a sarcastic comment about his absence.

I should note that Mandela at first had a hard time with Clinton; he had been very close to President Bush. He liked Bush because Bush called him periodically. I remember that during my first meeting with Mandela, I said that I had brought a letter from my President; I was then told that “I have a very good relationship with George Bush; he calls me whenever he takes some action that touches on South Africa even if he knows that I might not like it.”

But the inauguration was unbelievable. Hundreds of thousands of people showed up to cheer Mandela, many from all corners of the world. Mandela walked to the dais, followed by all of the chiefs of staff. He took his seat in the front row; the military chiefs sat behind him. Colin Powell, who was a delegate, said “That is the transition.” Mandela gave a great speech; de Klerk became a second Vice President, which was a very gracious gesture.

Mandela offered a spirit of reconciliation. The feeling among whites and blacks alike was that finally South Africa was free. The whites were freed from apartheid, with all of the condemnation that went with it.

You can listen to his inauguration speech here.

Comments are closed.