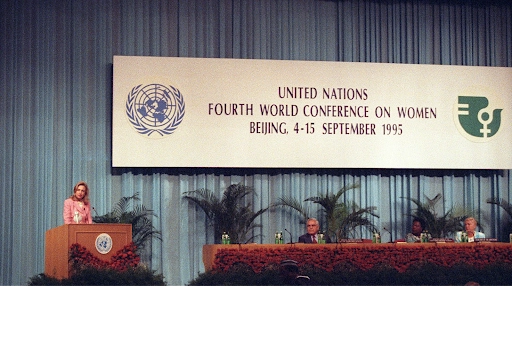

“If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights once and for all.”—First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton

At the United Nations’ 4th World Conference on Women, which was held from September 4-15, 1995, several countries united in support of women’s equal rights to life, education, and security across the world. The conference crusaded for female empowerment and women’s inclusion in national and international decision-making. Discussions on such controversial issues as contraception, reproductive rights, and equal inheritance allowed advocates to raise women’s rights to the forefront of international diplomacy. Once the conference had ended, however, nations, including the U.S., struggled to incorporate those precepts into foreign policy or to negotiate with those countries that violated conference principles.

In the following interview with Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning May 2007, Peter David Eicher, who was serving in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL), recalls his experience of the Beijing Conference, the unlikely alliances, the ways of finessing compromises, the hard work of implementing those commitments, and the tortuous road on reform in China. See also the Moment on Trafficking in Persons.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“The Bible for the international women’s movement”

EICHER: I think the very first thing I did when I got to the Bureau was immediately to run off to Beijing to attend the 1995 UN World Conference on Women. Hillary Clinton went to that, indeed. She was the leader of the U.S. delegation and she made quite a splash and a very good impression with her work there. She was seen as a real hero by most of the women in attendance….So I spent two or three weeks in Beijing, in one of these massive multilateral negotiations, trying to put together the Beijing Declaration and Program of Action.

For me it was very familiar territory. It was a big UN conference, not so different from the World Conference on Human Rights, which I had participated in a couple years earlier in Vienna. In fact, there were a lot of the same issues and a lot of the same people were there, so I felt very much at home. We were working towards a similar goal, to try to get an international consensus on a single document with a broad set of issues.

This time, of course, the document was on women rather than on human rights—the themes were “equality, development and peace” – but lots of the issues were really human rights issues. By the time we got to Beijing, there was already a pretty good outline or draft of the program of action, which ran on for two hundred or so pages. It set out all kinds of things that countries, NGOs, and international organizations ought to do in a whole range of fields to promote a better life for women. It covered health issues, economic development, education, physical protection, and a lot of other issues, including women’s rights. Women’s empowerment was a big theme….

What I personally ended up spending most of my time on in Beijing was what came to be called the “Beijing Declaration.” [Go to the UN site to read the Conference documents in full.] The pre-Beijing negotiations had developed this very nice, lengthy program of action – which still had a number of controversial points but which was in reasonable shape – but nobody had done anything about a preamble or a lead-in document….This would be the “Beijing Declaration,” which would be a general statement of goals and principles, just a couple of pages long. The outcome of the conference – the document adopted there – was called the “Beijing Declaration and Program of Action,” being a combination of the document I worked on and the much longer program of action I mentioned before….

The long Beijing document was, in fact, read by many, many people and even became sort of the Bible for the international women’s movement for the next several years….It was sort of a microcosm of all the big issues that were included in the program of action, but in more general terms. And since we had to use much reduced language, it made for a new negotiation on many of the key points as well as some extraneous ones, as each delegation tried to get its favorite political points included. There was even some language on arms control and disarmament included….

I was also surprised that with such a big, high-powered delegation, I was the one who ended up doing most of the Declaration. With my human rights background, I spent most my time trying to get human rights clauses into it. With the help of a lot of the Europeans and others, the Beijing Declaration was very heavily human rights-focused, with many paragraphs dealing with the rights of women. So we found that to be a very nice victory.

On the whole, the Declaration was pretty good, as were the results of the conference in general. Although there were a lot of controversial issues, all in all the delegations wanted to do the same kinds of things and the negotiations in general were not nearly as hard fought as at other international negotiations I’ve been involved in.

Negotiating on Birth Control and Women’s Right to Inheritance

In my negotiation, the main issues that seemed to spark controversy were really various human rights issues. Some of the countries with big human rights problems wanted to avoid human rights issues to the extent possible, and that made me and like-minded delegations even more determined to include as much as possible. I found myself in a very strong negotiating position because just a couple of years before, at the World Conference on Human Rights, these countries had agreed to a lot of principles and language that they didn’t like very much and it became very awkward for them to try to say two years later that, “Well, in the context of women, we really don’t believe these things anymore….”

At the very end, a couple of the members of the U.S. delegation decided they didn’t like the language on environment and economic growth, which was really quite innocuous, but didn’t include some catch phrase they would have liked. Since the language in question had already been adopted, this led to a long negotiation on a new, additional paragraph in which many delegations tried once again to include all of their favorite issues….

Birth control was an issue. It was not really my issue, so I was not involved in the negotiations on that and can’t tell you much about how they went. I do know that “women’s reproductive rights,” as the issue was referred to, was a big, controversial issue and there were a lot of people spending a lot of time negotiating on it….

The United States was taking a progressive view on women’s reproductive rights but a lot of countries were not. It made for a strange set of alliances, since most of the Latin American countries, which usually side with us on human rights issues at these big conferences, are very Catholic and had positions that were strongly anti-abortion. China, on the other hand, which is usually against us on human rights issues, is very pro-abortion. So sometimes it was strange bedfellows. But, eventually they came up with some compromise language that everybody could accept. I cannot recall exactly what it was. In the Declaration, which I was working on, we did work out some language about the right of women to control their own fertility, which was positive, but it was very brief and didn’t specifically mention abortion….

One issue that was very controversial, which had an interesting outcome was the question of inheritance rights for women. This got to be a big issue with the Islamic countries because Islamic law, sharia, sets out very specifically what women are entitled to inherit and it’s not equal to what men get. So the Islamic countries were opposed to the right to inherit equally. [Representative from New York] Geraldine Ferraro was the one who was working on this issue for us and I remember her describing the difficulties in finding a compromise. Eventually, the solution worked out in the conference document approved women’s “equal right to inherit” rather than their “right to inherit equally.”

The upshot was that everybody has an equal right to inherit, whether they’re men or women, but they don’t necessarily get to inherit the same amount. The U.S. delegation accepted this, as everyone else did. In fact, in a way it does reflect U.S. practice. Gerry Ferraro explained that “look, you know, if I want to leave all of my wealth to my son or leave it all to my daughter that should be my choice. I shouldn’t be forced by some international standard to divide things up equally if I don’t want to. They should all have an equal right to inherit, but that doesn’t mean they should always inherit equally.”

Heroes of the conference

[Hillary Clinton] was very popular. She gave her keynote address and it was standing room only. She brought the house down. Generally people don’t listen to speeches at these conferences, but everyone was very intent on hers. People were applauding and giving standing ovations. She was extremely impressive as the public face of the delegation. She was not there the entire time. It was a long conference, as I said, two or three weeks. This included a pre-conference negotiating week.

I think she was there for a week or less and I don’t recall her being involved in the negotiations at all. But everyone wanted to meet her and I’m sure she used her meetings to press for the U.S. positions on various issues.

The U.S. slogan for the conference was “human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights.” We worked hard to get that into the Declaration as well, to get that phrase in. I guess that was an example of what I mentioned before, about every delegation trying to get their favorite language into the Declaration. We ran into a lot of resistance from people who said this is just a slogan and doesn’t really mean anything. Those were mainly the delegations who always oppose the U.S. on everything. We ended up getting half of it in but I can’t remember whether it was women’s rights are human rights or the other way around, but one of them is actually in the Declaration.

Hillary was regarded as one of the heroes of the conference, a very strong U.S. voice to try to ensure that the right things came out. On a day to day basis, the delegation was led primarily by Donna Shalala, who was the Secretary for Health and Human Services at the time, and by Tim Wirth, who was the Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs. Tim was a very good guy and did much of the day to day management and coordination of the delegation. Madeleine Albright was also there for at least part of the conference; she was still UN Ambassador at the time.

It was a huge American delegation. I think every woman in the United States wanted to get on to it. There must’ve been eighty or a hundred people on the delegation. Most were private individuals, some of whom seemed just to be along for the ride. Those of us from the State Department were definitely in the minority. We felt like we did most of the work, of course, and all of the reporting. I think there were three or four of us who traded off doing the daily reporting cables….

What was your impression of how the Chinese handled this whole thing?

EICHER: They were very, very intent on having a successful outcome to the conference and being seen as good hosts, so they were positive; they were flexible….I think the Chinese bent over backwards not to be obstructionist on any kind of substantive issue. I don’t remember them taking an active part in the negotiations, although their delegates were there in force. Actually, it was refreshing to see the Chinese being cooperative instead of obstructionist. They were desperate to have a successful conference, at which everybody agreed to something. That seemed to be far more important to them than exactly what was agreed.

The battle to mainstream women’s issues

When I got back to Washington, one of the things I tried to do out of the Human Rights Bureau, in my capacity as head of the Bureau’s working group on human rights of women, was to try to make sure that there was some kind of effective follow up to the conference. We were able to get the Secretary to send a cable to all diplomatic posts instructing them to follow up with their host country and listing a number of different issues that we felt they ought to pay special attention to and work on, especially with the people who had been members of the Beijing delegations.

We hoped we could start to build a new dynamic at American embassies that women’s empowerment issues, such as the ones we worked on at Beijing, were issues that were appropriate and worthy for attention by American embassies. All this was part of what we called “mainstreaming” women’s issues into foreign policy.

As far as I could tell, most posts didn’t take it too seriously at first. A year later, on the anniversary of the conference, I did another, all diplomatic-posts instruction, asking our embassies to follow up on how well their host countries were doing in implementing their Beijing commitments. So we were starting to build a new mentality in the State Department as well as around the world.

I think it was pretty tough all around. The geographic bureaus tended to be very protective of their territory and their policies. The functional bureaus in general and the Human Rights Bureau in particular, I think, were seen not only as backwaters but as interlopers. From the perspective of the geographic bureaus, we never sufficiently understood the strategic context or the local circumstances in whatever country we were dealing with, even if it was a country we had visited or served in ourselves. They thought that the functional bureaus, especially human rights, never took broader U.S. interests into account and so forth and so on.

There were a lot of bureaucratic battles, several of which I already described to you, occasionally even resulting in a so-called “split memo.” These were decision memos that would have to go up to the Under Secretary for Political Affairs, or even to the Secretary of State, to make the final decision when there was a dispute among bureaus on whether we should adopt one policy course or another. The Human Rights bureau usually lost on these….

The slow slog towards progress in China

One of the many battles we had, the annual drag-out, knuckles-bared fight on the China resolution at the UN Human Rights Commission was probably the worst….It was an extremely frustrating effort. Ultimately, we did win this one every year I was there, at least in the sense that we did co-sponsor a China resolution each year at the Commission.

But the China desk, through its bureaucratic maneuvering, was able to ensure that we did not do it effectively or vigorously enough.

The position which was ultimately adopted by the U.S. just about every year was that, “We’ll see how the situation is at the time the Commission meets and make our decision when the time comes.”

This has a certain logic in the sense that you can hold the threat over the Chinese and that perhaps they’ll come up with some prisoner releases or something in exchange for us dropping the resolution. But in terms of actually getting a resolution adopted, if you wait until the Human Rights Commission starts to decide whether you want to do a resolution on China, you’ve missed six months of trying to build political support for a resolution. The practical result was that since China never did enough, we had our embassies around the world rushing in at the last moment saying, “Oh, we just decided that the situation is still bad in China and you should vote for a resolution.”

Meanwhile, the Chinese had been spending the entire year with high-level delegations to every member of the Human Rights Commission lobbying against a resolution. So it was a very poor, very frustrating bureaucratic process indeed. Although this was one of the bureaucratic battles we won, it was a hollow victory in the sense that, while we sponsored a resolution, we never launched an effective campaign to get one adopted.

There was a progression going on in China. You couldn’t deny that the country was changing, and changing in a positive way. Certainly there was more individual freedom in some ways as the Chinese political system became less totalitarian. But this was individual freedom in the social sense more than the political sense. As long as people refrained from criticizing the political system and stayed out of politics, as long as they avoided criticizing the government, as long as they didn’t ask to be in a labor union that was independent, as long as they were satisfied with state-controlled churches, as long as they didn’t openly advocate anything that was against government policy, then yes, they were freer to choose what job they wanted to have or where they wanted to live. (Reuters photo)

These were important things, even though they were limited. China even started experimenting with village elections for the first time, which had the potential to become something very significant, although they had not yet become very widespread. So, yes, there were some changes and some positive things going on. It was really in terms of political rights, like freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of association, and political prisoners that things were still going badly.

China still had a huge, pervasive, system of political detention, “reeducation through labor” camps, where tens of thousands of people every year would be sentenced for terms lasting years, without any kind of a trial, just an administrative procedure. So there was change and some hopeful signs, yes, but still really enormous human rights problems.

Q: What about Congress? Did you have sort of fire-breathing liberals on one side and Neanderthal, right- wing Republicans on the other side?

EICHER: Congress was generally a big ally of the Human Rights bureau. And they still were big supporters when I was in DRL. To the extent we had leverage within the State Department, it tended to be because Congress had legislated or declared that human rights…had to be taken into account and had to be part of the policy process.

We did have a number of Congressmen who were real allies and we had the general sympathy of practically everybody in Congress, as far as I can recall. There was a Congressional Human Rights Caucus that we dealt with fairly regularly. [Representative from California] Tom Lantos, I believe, was the Chairman at the time…. Interestingly, some of the very right-wing Republican members of Congress were very libertarian and very supportive of human rights.