Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, departed Tehran on January 16, 1979 to seek medical treatment and to escape growing political unrest in the country he ruled. The Shah had consolidated his hold on power after the 1953 U.S.-backed overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh and was considered a vital ally to the U.S., a leader in fighting communism and promoting regional stability. Iran had been increasingly prosperous and the Shah’s grip on power unassailable.

Pahlavi’s fortunes changed when his “White Revolution” of social, economic and political reforms stalled with the end of the 1960s oil boom and his secret police (SAVAK) ramped up their vicious repression of political dissidents. Observers at home and abroad began to question the regime’s viability in light of reports of rampant corruption and human rights abuses. Self-aggrandizing acts by the Shah, notably an extravagant commemoration of the 2500 years of Persian monarchy held in the ruins of Persepolis, consolidated political opposition and propelled unrest into revolution.

Eleanore Raven-Hamilton, a Consular Officer in Tehran from 1975 to 1977, observed Iran’s political and economic unraveling beneath the regime’s attempts to portray to the outside an image of modernization and consensus. She was interviewed by Edward Dillary on November 18, 2009. John D. Stempel, Deputy Chief Political Officer in Tehran from 1975 to 1979, chronicled the speculation surrounding the Shah’s health, along with the regime’s inability to quell the mounting political disorder. Kristen Hamblin interviewed Stempel on August 3, 1998.

Please follow the links to read more about the coup against Prime Minister Mossadegh, the storming of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979, the decision to admit the Shah to the U.S. for medical treatment and an account of the 1979 Iran hostage crisis.

“Iran suggested to me … a facade with people at the top partying and people below struggling”

Eleanore Raven-Hamilton, Consular Officer, U.S. Embassy Tehran, 1975-1977

RAVEN-HAMILTON: Opinion on the future of the Shah was divided at the Embassy. Some people focused on the importance of Iran as a partner to the U.S., a strong military force in the region and a 45 major supplier of oil. Others expressed serious concerns about Iran’s future because of weakness in the Shah’s government, its rampant corruption, its repression and its ruthless secret police (SAVAK)….

The Shah had lost support with his flamboyant celebration in Persepolis of the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great. That was “the party of the century,” but mainly for international aristocrats and high society. There was so much propaganda celebrating him — the “King of Kings and Light of the Aryans” — and his rule.

While I was there, the Shah’s government changed Iran’s Islamic calendar to coincide with a date when the reign of Cyrus the Great — the Shah regarded him as a predecessor — could possibly have begun. Muslims, especially the clerics, would be very angry that the Muslim calendar had been marginalized. Most people, including us, were just confused as we struggled with the Islamic and Western calendars and with this new calendar. It was hard to know what year we were in. That was not an intelligent thing to do at all, I thought.

The Shah talked about modernizing the country and had made some changes in that direction but he had made enemies too, especially among the mullahs. Social changes may have come too fast for traditional Iranian society to absorb, while corruption and massive military purchases were devouring government money and the oil revenues….In their attempts to do what you might otherwise consider good things, they occasionally stumbled and did foolish things that hastened their decline.

For example, the Empress Farah was a great patron of the arts. The annual Shiraz festival was part of that. They brought lots of entertainers from Europe, ballets and so forth, but one of the ballet groups was a Danish ballet and at the time they were dancing half nude. And I don’t mean traditional ballet costumes. This was put on television, and I think a lot of people probably saw that – as television had spread across the country – and considered it either in bad taste, or sacrilegious, or immoral….

Despite the role of the U.S. government in overthrowing [Mohammed] Mossadegh, Americans remained popular….The U.S. was regarded as “the place to be,” trendy, exciting, modern, great universities, great music, and a great life style, welcoming new ideas and new people, a land of possibilities and the future — and a safe place for money.

The influx of oil money was enabling young people from all sorts of backgrounds to leave in droves to study in the U.S….

I wondered if Iranian society could absorb all this rapid change. It was such a big stretch. I had not spent much of the Sixties in the U.S., but I was aware of the effects of rapid social change in my own country, a country fairly well used to change, between the 1950s and the ‘80s. The social strains in the traditional society of Iran would be magnified many times from the strains we had seen, still see, in the U.S. as a result of the changes the U.S. had experienced. I worried that there would be a serious problem in Iran soon because of this rapid social change.

Iran suggested to me a massive Potemkin village, a facade with people at the top partying and people below struggling. I couldn’t quite understand what was happening early in my tour, but several colleagues with more experience in Iran than I had thought the Shah was really in trouble. So many people seemed to be “on the take,” and the oil boom economy was starting to look as if it were running out of steam — petering out.

“The Shah was loosening up politically at the same time economic conditions were getting worse”

John D. Stempel, Deputy Chief Political Officer, U.S. Embassy Tehran, 1975-1979

STEMPEL: It was clear by the summer of 1978 that there was severe unrest [in Iran] and it wasn’t going to go away. We had sent in cables in 1977 suggesting why this was going to be so.

…The Shah couldn’t make up his mind whether to conciliate or coerce and he got it in the wrong kind of rhythm so that when he was tough, people thought he was a bully, and when he was trying to be conciliatory, people thought he was weak….

The Shah was loosening up politically at the same time economic conditions were getting worse. As a couple of my best Iranian friends told me, if he had loosened up when conditions were good, he could have brought more people into the political system. But as it was, everybody felt alienated.

In 1963 when it became necessary to use the army — and I heard this story from someone who was with the people who went in — the Court Minister and Prime Minister went to the Shah and said, “Sir we have to use the army.” And the Shah gave his usual, “We can’t break the mystical bond of the Shah and the people with force.”

And finally the Prime Minister said, “Look, if you want to be Shah we have to let the army shoot.”…

The story varies as to whether the Shah nodded his head or let them go ahead with a tacit yes.

But anyway, they went out and gave the army orders to shoot and put in a curfew and it was touch and go for ten days, but after that it was over. The Ayatollah was shipped out to Iraq and other people made their peace with the regime and they had fourteen years of unbroken progress until 1977.

Now, was the Shah bad? Yeah, it was bad stuff. Was it improving? Considerably during the four years I was there. In fact, compared to what followed, the Shah looks like almost a saint, in terms of his human rights practices.

Amnesty International states that the Iranian revolution killed about 600,000 people in its first year. Nobody has ever suggested that the total killings in the Shah’s regime ever approached more than a few thousand over a course of a 37 year regime. But the Shah felt that he wasn’t being fully appreciated.

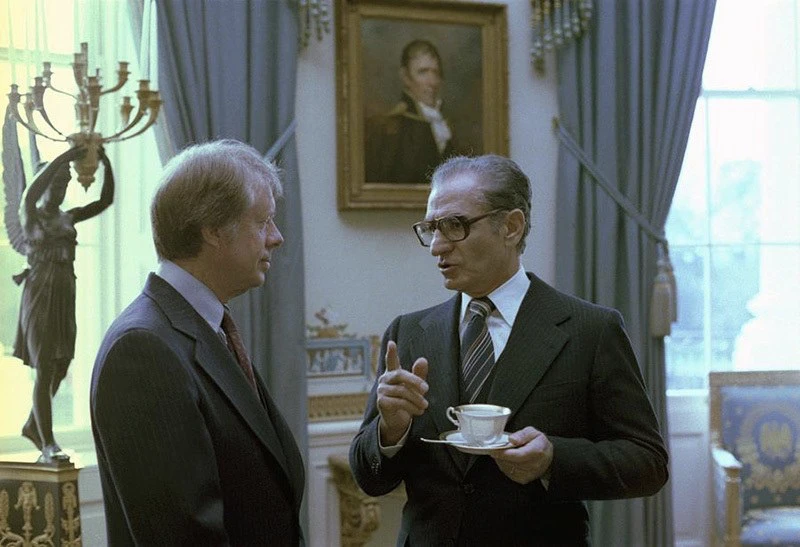

The Shah was a geopolitical type like Kissinger and Nixon, and he felt comfortable with them. Jimmy Carter was someone who was worried about civil rights and he didn’t feel comfortable with him. And the Americans put more emphasis on human rights and the Shah, I guess because he was sick, became distrustful. (President and Mrs. Carter seen with the Shah and Empress at right.)

The modernists felt that the regime, the Shah and his brothers and cousins, were ripping off the country, which was true. There was a lot of money going into slush funds in the Pahlavi foundation and things like this….What the vast majority of the citizenry wanted was modern, democratic government without the Shah. What they got was something entirely different, and that was the issue.

…In May-June 1978 the Shah, in effect, botched a reconciliation with Ayatollah Shariat-Madari, the other senior Ayatollah with authority. And we know now why. The Shah’s Commander of the Imperial Inspectorate was a Khomeini man and he probably was responsible for this botching of it. Because the Shah had humiliated him so many times, it was his way of getting back.

And then the Shah, himself, was a little bit sicker.

“You could buy reports that the Shah had everything from heart burn to lymphatic cancer”

….[The Shah] had successfully concealed [his illness] from his own wife for four years, and we did not find out definitely about it until the autumn of 1978 when we got a break from another country’s intelligence service. Now, in the process, though, we had found out about it in the sense that we had heard stories to that affect.

There was a moment in the spring of 1978 when you could buy reports that the Shah had everything from heart burn to lymphatic cancer, which he actually had, to lung disease or a stroke. And there were doctors’ pictures appearing in the press and it was just an interesting situation.

….Most people, up until November, 1977, the bulk of the Iranian people, and even at the time of the Jaleh Square riots in September 1978, were pro-monarchy. If the Shah had said “these people are threatening the country, we will open up the political system, but first we have to repress the poison in the system,” he could have wrapped up the whole Mullah movement, put these guys out in guarded camps in the desert, and gone on and made political changes.

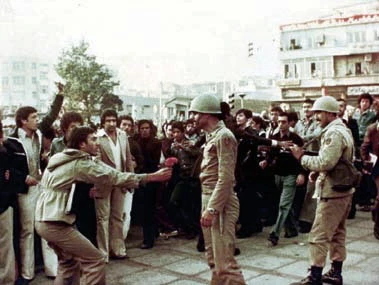

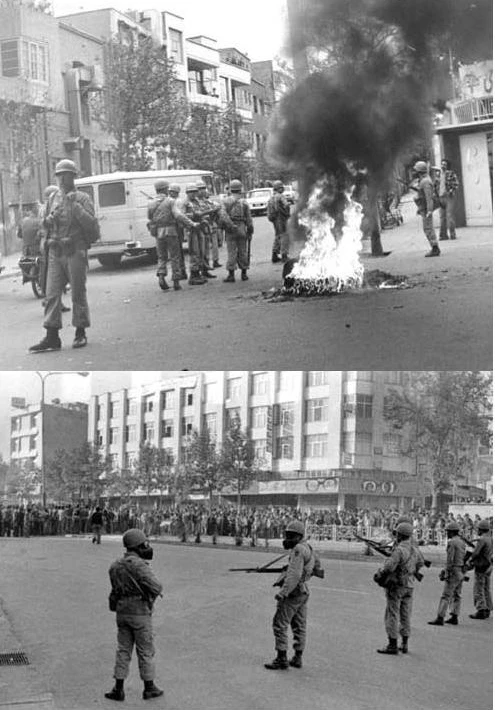

But he was paralyzed; he couldn’t do that. And as a result they just grew and grew and when it became obvious that the Shah wouldn’t use force…the army got mad enough and stopped protecting the streets in early November. There was a day of wild riot and chaos in Tehran; the Shah instituted martial law. But the army wasn’t allowed to shoot people who violated the curfew. It took them two weeks to find this out and then the revolutionaries just came back.

….Not many people who were in Iran at the time think that the Shah could not have imposed draconian martial law and retain power. Now, what would have happened later on had he repressed the Mullahs and the revolutionary movement in Iran? Then it would have been over. There might have been further terrorism and even a more difficult outcome down the pike, but he could have probably survived.

What he couldn’t do was be weak on one side and not be strong enough to retain power on the other. And the Ayatollah Khomeini played that carefully, first in Iraq and then in Paris, where he had access to world media. Until, by and large, he stripped away the layers of support from the Shah.

By December, when the Shah put in [Shapour] Bakhtiar as Prime Minister, a man who had opposed him, it was his effort to bring in an acceptable revolutionary to accept the monarchy. Khomeini wouldn’t even take that. Bakhtiar lost all the revolutionary support and then it was just a question of what was legitimate.

By the time Khomeini came back to the country on February 1, the Shah had left on January 16 and everybody knew he was gone for good, although that wasn’t the way it was billed. Ninety-eight percent of the people celebrated. I was out in the streets often that day and everybody was delighted that the Shah had left. Everybody thought they were going to get something different.

….Everybody celebrated Khomeini’s arrival because he was going to put in a government…He had named [Mehdi] Bazargan Prime Minister — again somebody I had been talking to for some time – along with a couple of his assistants, one of whom I had been dealing with for a substantial amount of time, as the shadow government.

Khomeini had been there about two weeks, I guess… The army, the Imperial Guard, was still loyal to the Shah, but there was a riot at Doshentapi Air Base on February 9 and the Imperial Guards sent two divisions down to put it down and they were bushwhacked. The air cadets distributed weapons from the arsenal there. The Imperial Guard commander was killed and then it just degenerated.

At that point there was no government to take over. It just fell apart and the Liberation Movement people moved in. Two days later there was a new government. It just turned over. And then, of course, the killing started.