Ambassador Jonathan Addleton

Oral Histories of U.S. Diplomacy in Afghanistan, 2001–2021

Interviewed by: Joe Relk

Initial interview date: December 3, 2022

Copyright 2022 ADST

Q: This is an Afghanistan project interview with Ambassador Jonathan Addleton. Today is the third of December 2022. My name is Joe Relk. We’re conducting this interview virtually. I’m in Virginia and Ambassador Addleton is in Pakistan. The interview is being conducted under the auspices of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and the focus is on Afghanistan.

Ambassador, I’d like to start with some context. If you wouldn’t mind providing an overview of your career prior to coming to Afghanistan and sort of how you leveraged that and your post-State Department career.

ADDLETON: Thank you. Yes, this is Jonathan Addleton speaking from Lahore, Pakistan. I joined the Foreign Service in 1984, ten years after completing high school. I was born and raised in Pakistan and so I had this aspect as part of my background from the very beginning. I did my undergraduate education at Northwestern University [1975–1979] in Evanston, IL and my graduate school at Tufts University [1980–1984] in Medford, MA.

I joined the Foreign Service in March 1984 as a USAID [United States Agency for International Development] officer, returning to Pakistan for my first four-year assignment [1985–1989]. Looking back, it is interesting to remember that the Soviets were in Afghanistan at the time. Actually, I had been asked if I wanted to be assigned to the Afghan Affairs Office at the U.S. embassy in Islamabad. I chose not to. I felt I wanted my first USAID assignment to be focused on Pakistan. But at the margins I was aware that USAID was involved in providing humanitarian assistance to Afghans inside Afghanistan and that the U.S. was also supporting the Mujahideen effort more broadly.

That was the start of my Foreign Service career, and I was a USAID officer for most of it. I met my wife Fiona in Islamabad––she was from Scotland; we went on to have three children, Iain, Cameron, and Catriona. We basically tended to gravitate to the so-called “hard places”, which we actually enjoyed. Those were the places we wanted to experience. So, it was Pakistan first [1985–1989] and then Yemen [1989–1990] which later became caught up in the first Gulf War; later it was South Africa [1990–1993] during the waning days of apartheid and then Kazakhstan [1993–1996], then emerging from the demise of the Soviet Union. We covered all Central Asia, all five “Stans”––Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan. It was a fascinating time to be there. On a couple of occasions, I was close to the Afghan border including during a trip to southern Tajikistan where I traveled along the Wakhan Corridor, looking across into Afghanistan and Pakistan beyond, to Tirich Mir, highest mountain in the Hindu Kush.

After Central Asia I was assigned to Jordan [1996–2000] at a time when there was hope about a potential peace settlement. It was a fascinating time to be in the Middle East and we visited Egypt, Israel, and Syria on several occasions. From Jordan I was assigned to Mongolia [2001–2004], my first experience as USAID mission director, albeit as head of a very tiny USAID mission though I would argue a very successful one.

As it happens, there are more similarities between Mongolia and Afghanistan than one might immediately think, at least in terms of being landlocked and surrounded by powerful neighbors. Indeed, Mongolia later participated as a member of ISAF [International Security Assistance Force]. The Mongolian soldiers provided security at Kabul Airport for a time; they also provided helicopter and artillery training for the Afghan military all those years later, accustomed as they were to operating Russian-made equipment.

In fact, years later––when I was ambassador to Mongolia––the Mongolian Foreign Ministry sponsored a program for Afghan diplomats that involved training in Mongolia. It makes sense. And I have to say that Mongolian diplomacy so far has been successful in maintaining that balance between two powerful neighbors, in their case Russia and China. It was an interesting diplomatic exchange program and represents another contribution that Mongolia has made in the post 9/11 world, beyond participating in ISAF and sending soldiers to Afghanistan. In addition, Mongolia provided a certain number of scholarships for Hazara students from Afghanistan to study in Mongolia, reflecting perceived affinities between Afghanistan’s Hazara minority and Mongolia.

Anyway, after a three-year assignment in Mongolia I was transferred to Cambodia [2004–2006], again as USAID mission director. After that I returned to Pakistan [2006–2007] in the aftermath of the earthquake in October 2005 that devastated much of the northern part of the country. Given my background in Pakistan, I was asked to take on this assignment.

Our relationship with Pakistan has been up and down and frankly terrible at times; in recent decades, it has been shaped to a considerable extent by events in Afghanistan. That said, work related to earthquake reconstruction was mostly a positive moment in our relationship, at least in terms of being part of a united international effort to rally around Pakistan during a time of extreme humanitarian need. So, I went to Pakistan for fourteen months, focusing on earthquake reconstruction while also engaging in some issues related to both Afghanistan and the “regular” development program in Pakistan.

By this time, I had been in the Foreign Service for more than twenty years, was approaching fifty, and could consider retirement. I had never served in Washington, DC and I briefly considered bidding for an assignment there, if only to ensure that our children had an experience of the United States before attending college. However, in the end I was assigned to Brussels [2006–2009] as the USAID representative to the EU [European Union], my first and only European assignment. So that was a comfortable assignment as far as creature comforts are concerned although in some ways it was harder than you might think. Basically, though, it was an interesting time to be there. Of course, by this time the U.S. was deeply engaged in Afghanistan and some of the work I did as USAID representative to the European Union was to liaison with the EU countries about things that were happening in Afghanistan as they related to development and humanitarian assistance.

The next part of my Foreign Service journey involved an unexpected assignment for a USAID officer––to return to Mongolia [2009–2012], this time as ambassador. Of course, it is a proud thing to represent your country and I had three great and wonderful years as U.S. ambassador to Mongolia. At the end of that assignment the prospect of retirement again emerged, at least in my own mind where I asked the obvious question: “What do I do next? Do I retire or what?”

I did seek out––well, maybe “seek out” is too strong a word––rather, I should say that I was aware of the senior civilian representative [SCR] positions in Afghanistan, some of which were encumbered by former ambassadors. I always considered myself a field person which meant that if I served in Afghanistan, I was more interested in serving somewhere other than Kabul. And so I called up Ryan Crocker, the then-U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan who I had previously served under in Islamabad. He is a very tough guy to work under and I wasn’t even sure what he thought about my performance in Pakistan after the earthquake. However, he encouraged me to consider Afghanistan and so I applied for the SCR position and got it.

This also meant that Afghanistan was the second time in my career when I was seconded to State––for me, Afghanistan was not a USAID assignment, rather it was another State Department assignment, albeit one involving a USAID component. For reasons that will probably be apparent when I describe my year in Kandahar, I did think about retiring afterwards.

Yet once again I hesitated––the reality is, I loved being in the Foreign Service. That was where I belonged and so after Afghanistan I had two sort of farewell assignments, both back at USAID. Basically, it involved two years back in Central Asia as USAID regional director for Central Asia based in Almaty, Kazakhstan [2013–2015] which we enjoyed immensely, and then two years in India [2015–2017], which helped round out my perspective on South Asia in a positive way.

While in Delhi, my wife Fiona got involved with Afghan refugees in a number of interesting ways. So, looking back, we have been observers to what was happening in Afghanistan from a variety of vantage points. Perhaps that partly explains my willingness to volunteer to serve in Afghanistan: I was familiar with the neighborhood; I realized it was one of the big issues facing our country at the time; and I felt that I could contribute in one way or another.

I also had a historical perspective. Indeed, when I graduated from high school in Pakistan in 1975, I took a bus––well, a bunch of buses and trains, actually––going from one town to another. Along with two high school classmates, Mark Pegors and Steve McCurry, we went overland from Peshawar to Paris, passing through various cities in Afghanistan including Kabul, Ghazni, Kandahar, and Herat along the way; from Iran we crossed into Turkey.

While serving in Afghanistan during 2012–2013, I occasionally recalled that trip, and evoked it in my conversations with Afghans as SCR. Usually, it evoked a positive feeling, if only because Afghans tend to look back at the 1970s as mostly “good years,” especially in light of what was to come. I also realize that Afghanistan is now a permanent part of what I myself have become. As it happens, both Central Asia and South Asia have been recurring themes throughout my career. In that sense, Afghanistan has always intrigued me, perhaps in part because it is arguably simultaneously situated in both South Asia and Central Asia, the two parts of the world that have interested me most.

These are some of the dynamics that played out in my decision to volunteer to serve in Afghanistan. I was intrigued by it, and I felt I had some background related to it, both in South Asia and Central Asia. I mean, I spent twelve years of my career in Central Asia––six years covering the “Stans” and six years in Mongolia. In addition, I spent another six years of my career in either India or Pakistan––not to mention the twenty years I spent in Pakistan before even joining the Foreign Service.

So, as ambassador to Mongolia, I indicated an interest in serving in Afghanistan and ended up being assigned as the U.S. Senior Civilian Representative [SCR] to southern Afghanistan based in Kandahar. As part of that assignment, I was asked to connect with the Third Infantry Division at Fort Stewart near Savannah, GA, which even then was preparing to deploy in southern Afghanistan.

I returned to the U.S. for a brief TDY [temporary duty] to Fort Stewart, participating in some of their preparation exercises, lasting about one week. I then returned to Ulaanbaatar to finish my ambassadorial assignment, taking a brief period of leave before going to Kandahar. Fiona and Catriona stayed in Mongolia. I think this was the first time any Foreign Service officer ever “safe havened” in Mongolia. I had to request special permission from both the State Department and Mongolian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to do it. However, Catriona was a senior in high school and this arrangement would allow her to graduate with her class at her old school in Ulaanbaatar. Meanwhile, Iain and Cameron were in college––Iain was at Davidson College in North Carolina and Cameron was at Georgia Tech. So for that year in Afghanistan our family was widely spread out: Fiona and Catriona in Mongolia; Cameron in Georgia; Iain in North Carolina; and myself in Afghanistan.

Q: So, tell me a little bit about, so we have some context for you, and before and after Afghanistan, but Afghanistan itself, tell us about the senior representative position, how it fits into the structure there, and a little bit about Provincial Reconstruction Teams [PRTs]. And I assume you had the DSTs [District Support Teams] as well, the District Provincial Teams. So, if you could explain how that all worked while you were there, how many people and how it got along. And if you could maybe weave into that also your thoughts on this structure. Was it the right mix, was there a better way of doing things, how it worked with the Afghans.

ADDLETON: As I mentioned, I arrived in Kandahar in August 2012. I was basically there for twelve months, up until August 2013. I did a certain amount of research beforehand, but I guess I was just prepared to take it as I found it. As it turns out, 2012 and 2013 marked the transition from the height of the surge to a rather steep decline, at least as far as U.S. soldiers and civilians in southern Afghanistan are concerned.

As SCR––Senior Civilian Representative for southern Afghanistan––I reported to the U.S. embassy in Kabul. Basically, we covered four southern provinces. We had Provincial Reconstruction Teams situated in two of those provinces, Kandahar and Zabul; we also had a District Support Team in Panjwai, south of Kandahar, in an area that was viewed as highly kinetic. At least initially there were other DSTs as well, all of them on a path toward closure. I would have to go back and confirm the facts. But as I recall I was responsible for approximately a hundred and twenty U.S. civilians situated in as many as a dozen places spread across southern Afghanistan.

Uruzgan was a third province within our area of activity. It was basically overseen by Australia and Australia had its own SCR assigned to Tarinkot, the capital of Uruzgan which I visited from time to time. Parenthetically, a UN [United Nations] SCR was assigned to the south as well, representing UN interests in southern Afghanistan. All this is to say, at least as far as southern Afghanistan is concerned, it is perhaps best to think of us as a very modest civilian presence amidst a very large military presence.

I should also note that there was a fourth province in our area, in addition to Kandahar, Zabul, and Uruzgan, namely Daykundi, situated in the mountains of Central Afghanistan and including a large Hazara population. If I’m not mistaken, the mayor of Daykundi was a female from the Hazara community, possibly the only female mayor in Afghanistan. As it happens, graduating students from schools in Daykundi did surprisingly well in their national exams, considering the remoteness because many Hazara families put an emphasis on education including for females.

I tried twice to visit Daykundi from Kandahar. However, I was thwarted both times because of bad weather. I think I can say with almost complete confidence that there were no ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] casualties in Daykundi throughout my year in Afghanistan––indeed, it may be that there were no such casualties in Daykundi during our entire twenty-year engagement in Afghanistan. Probably there were few casualties involving Afghan security forces and the Taliban––but not many.

I make this comment because––and I know you’ll remember from your own experience in Afghanistan––there was a strong interest in supporting the central government; that was part of our message, that we are going to strengthen the central government in Kabul. Against that backdrop, it is ironic to think that Daykundi probably ranked among the quietest and safest places in Afghanistan––and it was run more or less independently, with minimal involvement from Kabul at all.

Of course, the converse to this comment is that decentralized approaches imply a strong role for local warlords which certainly have their negative aspects. However, it seems to me that in Daykundi it was the ethnic dynamic related to the Hazara community that was played out in a positive way, because it was indeed a very out-of-the-way part of the country with minimal strategic value and few links to Kabul. Looking back, it is intriguing that two of the four provinces in which I was involved had a huge military presence, one of them [Kandahar] being viewed as the heartland of the Taliban and the other [Zabul] considered as a main conduit on the Taliban supply route to Pakistan. As for Uruzgan, it was primarily the responsibility of the Australians while Daykundi was the most peaceful place of all.

It is also worth noting––and I mentioned this at a talk involving the journalist Ahmed Rashid at a seminar here in Lahore only last night––that Afghanistan is usually viewed as a mostly U.S. effort or a mostly NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] effort. However, what struck me during my time in Afghanistan was that the military presence I sometimes encountered went beyond NATO, including for example a Jordanian presence. Whether NATO or not, a range of countries were represented including the Romanians who kept the road north to Kabul open. Also, I would regularly see flags from places like Albania and Bosnia as well as Jordan flying at Kandahar Airfield [KAF], all representing countries with a majority Muslim population yet were somehow engaged in Afghanistan.

All this is to say, in my view the diverse international presence was a remarkable feature of the ongoing effort in Afghanistan at that time. In fact, this became a talking point in my conversations with Afghans, as reflected in my occasional comment, “My goodness, there will probably never be a time when there is as much international interest in or support for Afghanistan as now.” This international aspect also struck me in my occasional visits to ISAF headquarters in Kabul, outside of which flew the flags of dozens of countries. As I mentioned, the Mongolian flag was also included among those flags. So, from my perspective, the broad international presence was a fascinating part of the dynamic in Afghanistan during those years.

Another way to look at my time during that year in southern Afghanistan was that I was simultaneously engaged in three different worlds. One of those worlds was the military world which was certainly the dominant one. Here I am referring to the Third Infantry Division under General Abrams, one of my main interlocutors throughout my time in Kandahar. At some level, I was also the liaison person between the U.S. military presence in southern Afghanistan and the U.S. embassy in Kabul.

The second world that I was part of was the broader international world, involving as it did the international community comprising both soldiers and civilians from other countries. The UN effort was part of this world as well.

Finally, I was also engaged with the world of the Afghans, again serving as a sort of liaison between the people of southern Afghanistan and our embassy in Kabul. Of course, I was briefed by our embassy in Kabul before taking on this assignment. As I remember it, the “core” message that I was responsible for delivering to Afghans in southern Afghanistan as part of my ongoing outreach and engagement was (1) we need to work together to make Afghanistan a more centralized state; and (2) the ISAF chapter in Afghanistan is now drawing to a close.

Remember, this was as early as 2012–2013 and the so-called surge that established PRTs and DSTs across the country was already in steep decline. In retrospect, people can argue over whether it made a difference or whether we should have continued in the efforts facilitated by the PRTs and DSTs for a longer period of time. However, for those in the field––as you will also remember––it meant their engagement as members of a PRT or DST would also end, and we would be pulling out of some locations within a matter of months. Over time, the cliff kept getting steeper. Certainly, when I arrived in Kandahar in August 2012, I did not think that our own presence in southern Afghanistan would be reduced to a single location at Kandahar Airfield by the time I was scheduled to depart one year later. In that sense, I arrived at the tail end of the PRT/DST era of the ISAF engagement in Afghanistan.

Most of our people in the field thought that was too early. You can talk all you want about what it was like to live in a PRT or DST or what drew people to volunteer for such service in the first place. But, whatever their motives, the people I saw seemed very committed. And the almost universal feeling was that the drawdown was too steep. This was reflected in our reporting as well. I’d have to check the figures. But as I recall a hundred and twenty official U.S. civilians were posted in southern Afghanistan when I arrived in August 2012 and by the time that I departed in August 2013 the number was meant to decline to approximately forty. Put another way, I was not in Afghanistan when we were reaching out via the PRTs and DSTs to rural populations; rather, the task for me was to squeeze what might be possible during these last months while also attempting to turn the programs facilitated by the PRTs and DSTs over to Afghan counterparts. Parenthetically, despite the drawdown I had a lot more mobility during that year than outsiders might have imagined––I traveled across the region and talked to many people, usually traveling by military helicopter and with a military escort.

Against that backdrop, now is probably a good time to mention three quotes that I have carried around with me ever since my time in Afghanistan. I still remember them all these years later and I sometimes evoke them, as I did last night at this seminar in Lahore involving the journalist Ahmed Rashid as well as Andrew Wilder from the U.S. Institute of Peace [USIP] in Washington, DC who has lived in Afghanistan and has tracked Afghanistan for many years. I’ve had to process some difficult things since leaving Kandahar, but I still remember these quotes quite vividly.

First, in my conversations with Afghans I would often refer to Afghan history and compliment them on the courage and commitment to independence displayed throughout that history. I would then sometimes mention that the ISAF chapter in Afghanistan’s history was now ending, and it would be for the Afghans to write the next one. And at that point more than one Afghan would look up and say, “No, no, no. When you leave, it is not Afghanistan that will write the next chapter of our history; it is our neighbors that will do it for us.”

At the time I thought it was an interesting observation. Of course, when you relate that story to an audience in Pakistan, they know exactly what you are talking about. In fact, Ahmed Rashid who has written extensively about the Taliban and Central Asia and presented at the Lahore seminar last night basically commented that Afghanistan should be given the opportunity to develop independently, without its neighbors always interfering or intervening––something that in the context of Afghanistan is hard to pull off, given its land-locked location surrounded by more powerful countries. So that is quote one, as expressed by some of the Afghans that I talked to, that “Afghanistan is not going to write the next chapter of our history, it is our neighbors that will write it for us.”

Second, when I talked about the forthcoming departure of ISAF, one Afghan interlocutor, an Afghan tribal leader I was talking to, immediately commented, obviously with a rhetorical flourish, “No, please don’t; please leave just one American soldier behind.” Of course, he did not mean that literally. But what he is basically saying is, “Just show us that you care, just let us know that you are not entirely out of here, that we have not been completely abandoned.” And now, when you look back at events seven or eight years later, the basic message here was fear about abandonment. And here’s this guy telling me back in 2012 and 2013, even pleading almost, “Just leave one soldier behind.” In retrospect, the implication seems obvious enough: “We need to step up but please don’t abandon us completely.” So that is quote two, another of the fleeting images of Afghanistan that I continue to carry around with me.

The third quote is a bit more complicated. In this case, I was visiting someone who was clearly a Taliban sympathizer, and I was relating to him a recent incident in which a government office was attacked by a young suicide bomber, probably around fifteen or sixteen years old. He had exploded his bomb and the one casualty was a twelve-year-old kid, killed because he happened to be accompanying his father to work that day.

Some might say my comment in this context was ludicrous or stupid, considering we were in a war zone. However, from my perspective it was all about trying to establish a human connection, however tenuous, whether that connection involved a Taliban sympathizer, a tribal leader, a soldier, an economic player, or anyone else. In this case, I tried to do it by reflecting on tragedy, wondering out loud what the person who equipped the suicide bomber might say on judgement day. In this case, the response was as follows: “Yes, it’s a tragedy, this stuff shouldn’t happen. But in our country, there will be no peace without justice,” or words to that effect.

Ironically, Afghanistan is not the first place where I heard this expression; in fact, after graduating from Northwestern I had an internship with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in which I worked with Michael McDowell, a journalist from Ireland who mentioned that the IRA [Irish Republican Army], often evoked these exact words, almost as a slogan: “No peace without justice.” I get that and at some level can even manage some sympathy for it. But I also think: A twelve-year-old kid, really? What kind of justice is that going to bring? I mention this as the third quote that I remember from my time in Afghanistan. And, ever hopeful, I do recall that a sort of peace eventually also came to Northern Ireland.

Again, this came up at the Lahore seminar last night involving Ahmed Rashid and Andrew Wilder. And what Andrew Wilder, in particular, was saying last night is very true, that at the end of the day you have to talk to people, you have to have a negotiation of some kind or another. And, on the one hand, this final quote, is partly about tragedy in a way that also hits home personally, having experienced some of this type of thing up close and personal. And yet, at a certain level, I am not at all sure that I buy into this glib soundbite asserting that there is “No peace without justice.”

Because my immediate comment is, “Well, what exactly do you mean by justice?” That would be the next question, because, for me there are certain boundaries that you cross over and when you’re killing kids, that is one of those kinds of boundaries which leads one to ask, “Well, what exactly do you mean by justice?” At the end of the day, I don’t care where anybody is on the political spectrum. I also get the meaning of the slogan “No Peace Without Justice.” But, in the next breath, you have to ask the next question, “What kind of justice are you looking for?” In my view, there are some kinds of justice that really are beyond the pale and randomly killing kids to achieve that justice is one of them.

So, those were at least three interesting quotes that I heard in Afghanistan and still remember to this day. Looking back, I think that especially the first two of these quotes––“Please leave just one soldier behind,” reflecting as it did a fear of abandonment; and, “No, we won’t write the next chapter of our history, our neighbors will write it for us”––seem quite prescient or at least revealing when you look back at what later unfolded in Afghanistan. Perhaps I didn’t attach that kind of significance to them at the time. But, looking back, I think they do speak to the situation we faced in an intriguing and even insightful way.

Q: If I could dig down on that a little bit, ambassador, on the second and third one, but I’ll start with that second one, this notion of keeping a U.S. presence in Afghanistan, and I’m going to fast forward a little bit to the fall of the government and last year and all of that, and to the degree you’re comfortable commenting on the policy side of this, how do you think we should have handled that? I mean, there were a lot of good arguments either way. I know there’s something called Afghanistan fatigue here domestically. That’s a real thing, and they were talking about shutting down the PRTs in 2006 because they’d been such a great success. And then, your comments about how they were talking about how you’re going to write the next chapter on your own back in 2012, correct?

ADDLETON: Okay.

Q: And there we were in 2021, right? Still there. It strikes me that there’s other parts of the world where we’ve had U.S. troops for much longer. And there was a cost benefit applied to that. What do you think, taking that comment from 2012 and projecting it forward, what might we have done differently, or do you think there was no getting around the tragedy of 2021?

ADDLETON: Yes, I’ve reflected on this at length. I realize that I don’t necessarily have any great wisdom to offer. You need to get, as you’re doing now, lots of different perspectives. I do have a perspective, though. It may be somewhat but not completely like yours. I realize that Afghan fatigue was real, and that many people were just sick and tired of Afghanistan. I get that part of it. However, just as I would sometimes evoke the quotes I heard from Afghans, I also made certain comments of my own that perhaps partly speak to this way of looking at things. Not everyone would be thrilled by these comments. However, my basic critique here was that we seem to have this feeling that we should be either “all in” or “all out”––when, in reality, the best place might actually be somewhere in between. The “all in” part of the argument was essentially that, if we are going to “win” this war we have to be “all in.” Or, conversely, if we are not serious about it and don’t want to “win” this war, then we should be “all out.”

Ironically, Andrew Wilder, my friend and colleague from the U.S. Institute for Peace, used a similar quote at that seminar last night, describing the situation as a “Goldilocks thing,” namely the point is to be neither “too hot” or “too cold” but rather somewhere in between. I was surprised when he said this because we haven’t kept in touch or compared notes on this subject.

However, his statement more or less echoed my own comments on the subject, making the case, as it were, for a “middle path.” I mean, at some level––and this is the part where I could be severely critiqued by other people and maybe understandably so––but, at some point it seemed to me that toward the end of our time in Afghanistan we were gravitating toward the right place, that right place being a contingent of about six thousand soldiers in Afghanistan, seemingly sufficient by that stage to maintain some measure of stability in Afghanistan. This comment mirrors to some extent the comment made by the Afghan guy who said, “Just leave one soldier behind.” By this time, we were down to six thousand soldiers. However, it was pretty much the same concept––by that point, a small and continuing presence involving a small number of U.S. soldiers might have been enough to make a difference.

You would have to look at the historic record to make sure. However, last time I looked at the tragic death of thirteen U.S. soldiers killed in that one incident at Kabul Airport that occurred when we were departing, if I am not mistaken the death toll in that one incident exceeded the entire number of U.S. soldiers killed in action in the previous eighteen months combined. In that sense, U.S. casualties in Afghanistan had by this time markedly declined. Moreover, the notion that this was simply “America’s War” or something like that is simply ridiculous, partly because that phrase diminishes the ISAF contribution, involving as it did many other countries; and partly––and perhaps even more so––because it diminishes the Afghan contribution.

In my view, it was this feeling of complete abandonment that caused the Afghan National Army to collapse. And I say that circumspectly. I mean, our oldest son served in the military and our second son is serving there now. Given his branch of service, I have no doubt that if the war had continued, he would by now have served on the front lines in Afghanistan. So there is a personal aspect to my views here. However, talking to Andrew Wilder last night, I see that we were more less in the same place in holding to this view that after two decades we were gravitating toward the right place in terms of the size, scope, and nature of our military presence. However, as a country we were by now in a very different place with respect to our engagement in Afghanistan; again, more than a few people were by this point simply sick and tired of it and wanted it to end.

Put another way, it seems to me that with a fairly modest presence we could have maintained an important measure of stability. Recalling that “one soldier left behind” quote from one of the Afghans I met, I have zero doubt that if we had left even one soldier behind, the Afghan military would not have disappeared so quickly. I mean, I met too many brave Afghans on that side of the divide––some of them brave, some of them willing to fight; however, when they saw that the U.S. and its allies were leaving, it was over for them as well.

Q: Yeah, I think that gets lost a little bit in the domestic conversation which seems to center around well, why didn’t they fight harder and that sort of thing. And then, that third comment you had, and this ties into the fall as well, which is how people perceive the Afghan government, how Afghans perceive their own government, why they didn’t feel more strongly about defending it. And why the Taliban had some success in influencing public opinion and gaining some popular footholds, certainly in parts of the country and then later culminating in the fall of the Afghan government. You’d mentioned that that third quote was from a guy you talked to that was a Taliban sympathizer or maybe had some ties to the Taliban. What, maybe if you could talk about how many of those folks did you talk to out there and how well did you feel like you understood the dynamic between you know, hearts and minds for the government, hearts and minds for the Taliban, or hearts and minds for people that really just wanted to get about their lives and not be overly political or pick sides. I guess it’s sort of a two-faceted question. What was your exposure to folks on the Taliban side, how well do you thought you understood what they were bringing to the table, and how do you feel like that we may have perhaps done a better job understanding how to shape things on the ground there in a way that could have either incorporated their concerns or ameliorated the popular support for the Taliban, or increased support for the Afghan government? Your personal experience on the ground and maybe project that out to things we may have missed and could have done better.

ADDLETON: Yes. I mean, if I’m reading it correctly, you mentioned––and others have mentioned this as well––that it was the Taliban who were successful in capturing the most important narrative of all, the one that says, “We are true Afghans here, the government regime is simply the hand-picked puppet of the foreigners”; there is no doubt that this specific narrative goes a long way in Afghanistan.

So, yes, that is an important part of it. I don’t recall that I ever had meetings with someone who was explicitly a member of the Taliban. That probably wouldn’t have happened or, if it did, I never knew about it. But I did encounter a wide range of views. Also, to some extent what we were hearing reflected a collective view, not an individual one. Often in Afghanistan, it is a community perspective that predominates. You are part of a group, and it is a balancing act that you are playing all the time. Of course, one looks for momentary personal advantage within that context. But it remains a balancing act, no matter which side you are on.

I felt that there was a broad range of views out there and that I was hearing many of them. And, at some level, I also came to believe that both ISAF and the U.S. military were perceived as more or less yet another tribe, one that had arrived on the scene recently yet now somehow needed to be taken into account and balanced amongst all the other ones.

For example, I met with a tribal letter named Akhunzada from time to time. He wore a black turban and looked like one of the Taliban. Yet I respected and at times even admired him. No doubt he had many enemies. But the reality is, he was a survivor. I would love to know what he is doing right now and if he survived yet another regime change. Because he was a person who reflected a significant level of personal gravitas and had some measure of a local following. He was a very soft-spoken guy, although I’m sure he also had a hardness about him; it is hard to imagine anyone surviving in Afghanistan without having this kind of hardness. If I am not mistaken, his longevity went back to the Russians and then the Taliban followed by ISAF; now he would wait and see as to what happened next week. If nothing else, he was certainly a survivor.

This perspective was also reflected in a trip I took to Kajaki Dam, which of course is in the Helmand valley. Here it was the chief engineer who was an exceptional figure. If I am not mistaken, his tenure went back to the Americans who had built the dam and then he continued running it when the Russian arrived; later, he kept the dam open for the Taliban and still later for ISAF. And I am quite sure he is still keeping the dam open, once again for the Taliban––if not himself, then his successors who he would have trained are helping to maintain this vital dam and keep it open. I don’t think he was political. Rather, he was an engineer that somehow managed to survive. And he did this by maintaining a complicated balancing act, one that involved making an accommodation with many types of people over the years.

These examples have helped form my thinking about Afghanistan. At the height of the surge, we must have had well over one hundred thousand soldiers in Afghanistan. Then we moved the number down to around sixty-five hundred, still enough to play an important “balancing” role in the country. Maintaining a military presence of that size might have made more of a difference than many people imagine from a distance.

Kandahar was of course the home of Mullah Omar, the initial leader of the Taliban; in fact, the current leaders of the Taliban, just like Mullah Omar before him, continue to live in Kandahar rather than Kabul, despite the fact that the Taliban have now taken Kabul. Again, recalling one of Andrew Wilder’s comments in our conversation last night, he mentioned that the Taliban may be running its own “post-mortem” in terms of why ISAF defeated them so quickly the first time around in the aftermath of 9/11. Ironically, though, he also thinks the Taliban are making many of the same mistakes that they made during their first time in power, during the 1990s. In any case and for whatever reason, while the Taliban once again now rules in Kabul, the leader of the Taliban continues to live in Kandahar which is kind of fascinating when you think about it.

In the parlance of the U.S. military, repeated meetings with people like Akhundzada were viewed as “key leader engagements.” For our part, we civilians living in southern Afghanistan conducted many of them. Sometimes we came away with little more than crumbs. Nonetheless, we based much of our reporting on these types of meetings.

In retrospect, I am amazed just how much Afghans from all walks of life were willing to talk to us––anytime, anywhere, and to almost anyone. I imagine it is partly because they thought our conversations might have more of an impact than they actually did. We did of course report on what we were hearing. However, our reporting was first vetted through Kabul before going further to Washington. And some of our reporting never got beyond Kabul at all. Put another way, it was “scrubbed” many times before seeing the light of day and becoming available to a wider audience. Of course, there were some things that did not get through at all. Realistically, I don’t think it would have made a big difference. However, I know it was a frustration for some of our people on the ground, feeling as they did that our version of events and conversations weren’t being reported as fully as they wanted them to be.

Q: Or sometimes it’s timely, right? By the time it gets––

ADDLETON: Well, yes, timely––that’s true and that is a good point; because the clearance process often took an inordinately long time.

Q: Ambassador, I thought we’d shift gears a little bit. I know you’ve got a background in USAID and we’ve heard some criticisms of projects that we’ve done. Of course, it was over a long span of time, and approaches change over time. What were your thoughts about the effectiveness of the development that we were trying to do down there, both through the typical USAID channel, but also through the military and even the State Department had some funds that they were applying? The conversation on this goes from everything from projects that were working to projects that people thought may have even, perhaps, been counterproductive. So, your thoughts on our development package while you were there.

ADDLETON: I’ll start with a positive story first. I now live and work in Pakistan and there is a product from Kandahar that a lot of people in Pakistan including myself buy regularly. In fact, it says it on the label: “Red Anar from Kandahar.” Anar is the word for pomegranate [in Dari, Pashto, and Urdu]. It is basically pomegranate juice. And at some level I was heartened when I arrived in Pakistan two years ago and realized that this product, which is marketed by Nestle, originates in southern Afghanistan.

During my time in Kandahar, we were making a big effort to market products from southern Afghanistan, widely known across South Asia for the quality of its fruits and nuts including grapes and pomegranates. In fact, we were told at the time that such products from southern Afghanistan commanded a premium price in the food markets of Delhi. Storekeepers would claim that a particular shipment was from Kandahar even if it came from somewhere else, simply because the reputation of these items from Kandahar was so high.

As part of this effort, we encouraged and even subsidized flights bringing food products from Kandahar to both Pakistan and India. So, arriving in Pakistan and buying “Red Anar From Kandahar” makes me think that we had some impact after all. (laughs) Because all these years and despite everything that is still happening in Afghanistan, some products from Afghanistan are still finding their way to Pakistan.

I also recently read an article in a Pakistan newspaper that basically said Afghan refugees from southern Afghanistan, in this case the Helmand Valley, are emerging as key developers in the agriculture sector in Balochistan, of all places. According to this account, these Afghan agriculturalists now living in Pakistan are basically using techniques learned during the time when agricultural projects were being launched in Afghanistan.

Having spent many years in work related to development, I have become a strong believer in the reality of “unintended consequences.” Perhaps these Afghan agriculturalists in Balochistan are refugees from the Taliban or perhaps they have lived there for years and should no longer be considered refugees at all. Whatever the case, they are following economic opportunities wherever they can find it. And in this case, they see underutilized land in Balochistan, a very water-short province; they also see an opportunity to cultivate crops that nobody would cultivate earlier which a different water-saving technology that they learned elsewhere now makes possible. So maybe some of these efforts made a difference after all, perhaps in unintended ways. Obviously, I’m grasping at straws here and no doubt the outlay for these kinds of programs would have been huge. But, still, not everything that happened related to development in Afghanistan was necessarily a total, abject failure.

Of course, the military was also involved in development projects, mostly using them to benefit or “buy off” local populations, whether that involved a school, health unit or something else. The USDA [United States Department of Agriculture] was also involved in southern Afghanistan. Perhaps they were responsible for successfully marketing “Red Anar from Kandahar” to neighboring countries. As far as I know, they also introduced other useful techniques such as growing grapes on trestles; perhaps they helped introduce those water-saving irrigation techniques to the Helmand Valley as well.

Of course, corruption always loomed large as a concern––though a concern that always seemed very difficult if not impossible to address. Construction projects were notoriously difficult to monitor. In retrospect, I do wonder if we could have developed a different formula, perhaps establishing a square feet construction cost standard, and then providing for reimbursement upon completion, verifiable via GPS or satellite photography. Certainly, a “simplified” and more “streamlined” approach might have made a difference.

That said, a USAID contracting officer might say, “You are only fooling yourself.” Certainly, the OIG [Office of Inspector General] guy that visited Kandahar––and I have fairly negative views about the entire experience––had a lot to say in terms of critiquing projects but very little to add in terms of how to actually implement them. Well, in fairness, the OIG did at times put forward certain ideas that might have made a difference. But realistically the development process as USAID has been involved over the years was probably too complicated to be effective in a place like Afghanistan where a war was also going on. No doubt our military interlocutors viewed our handbooks as mostly a lot of blah-blah-blah-blah. At one level, the USAID way of doing business didn’t lend itself to the type of development work demanded of it. But at another level, maybe the military approach was too much at the other extreme, involving as it did a sort of “passing out bags of money to buy friends” sort of approach. Then again that is the way the British approached the issue of development when they engaged with Pushtun communities in what is now northwest Pakistan. At the end of the day, it is disappointing to conclude that USAID never really got it right when it came to its contributions in Afghanistan.

Q: So ambassador, are you talking about SIGAR [Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction]?

ADDLETON: Yes, that’s right, I was referring to SIGAR when I used the acronym OIG. Perhaps I should add a few more comments here. I certainly respect the role that IGs [inspector generals] play. But I also think that SIGAR routinely displayed a kind of arrogance that I thought sometimes verged on the ridiculous. I would have had more respect for them if some of their officers had been involved in the real world of implementation at some point in their careers, rather than simply critiquing it or pontificating about it. Perhaps I am being unfair. However, my sense was that some of the people I met from SIGAR couldn’t manage their way out of a paper bag. Viewed from that perspective, it seemed to me that SIGAR lacked the credibility that comes with those who themselves have a track record in terms of actually implementing projects. The press lapped up any report from SIGAR. But in my view their desire for press coverage combined with their arrogance was at times counterproductive.

Q: Yes, lots of stories about centers built in the middle of nowhere and that sort of thing.

I was wondering if you had any thoughts about the scope of projects. There’s been some criticism that we should have gone smaller or maybe even not spent as much. But your thoughts on that and maybe the big money projects like Kajaki Dam, like the Ring Road, money well spent, or do you think we might have done things a little differently?

ADDLETON: Yes, that’s a tough one. I’ve got mixed views on this issue. I mean, multiple approaches were tried at various times including infrastructure projects such as roads as well as budget support for the social sectors. Also, the military funded quite a few small projects in an attempt to respond to immediate perceived needs as well as “buy” influence from within local communities.

The World Bank led the way when it came to budget support. Basically, the idea was to integrate development with wider government efforts at a sector level, rather than have individual donors “freelancing” various projects in which the government would have little if any involvement. It is fine to build a school––but where will the teachers come from to make that school effective; it is fine to build a clinic––but how will that clinic be staffed, once it is built? In such cases, an expensive school or clinic might later be turned by the local community into a barn for animals or a storage place for supplies.

I do think that budget support initiatives have merit, forcing you to at least work within a process and within a system that ultimately does need to be put in place. But at the same time almost any system I can think of is also penetrable to corruption of various kinds. Perhaps if you have a rough idea of how much it costs to build a school, you should let the government or local community build it and then reimburse them for it. But then there is the whole system of fictitious staff and even fictitious buildings that might not actually exist.

That said, the reality is that Afghanistan did experience significant improvements in a variety of social indicators throughout the period of ISAF involvement. In fact, in terms of school attendance, infant mortality, life expectancy, female participation, and a range of other indicators, Afghanistan registered dramatic improvements, improvements that are now under severe threat now that the Taliban is back in power. Put another way, Afghanistan experienced more success related to health and education during those years than they are usually given credit for.

Against that backdrop, I don’t fault the effort to move forward with a handful of major infrastructure projects. For example, I do think that Ring Road was something worth pursuing. I don’t know how much of it is left right now. Despite the cost, I am not going to be overly critical of the attempt to put at least some improved infrastructure including roads and power systems in place. Again, perhaps certain approaches––build “x” many miles of roads and receive “y” amount in return––might have worked, rather than have USAID contract directly for a specific project. That said, it is easy to “second guess” at this point. The reality is, in many cases it is a situation of choosing the “least bad” rather than the “best” approach.

In fairness, a lot of people tried very hard––without achieving obvious success. I am sure there were more than a few cases of fictitious payrolls or buildings that didn’t serve their purpose. No doubt SIGAR served a useful purpose in drawing attention to failures. Probably they had a few useful suggestions as well, such as attempting to use satellite technology to verify construction in out-of-the-way or dangerous places. Probably, it would take a much longer conversation to disentangle all the many issues involved.

One final thing that is important to say is that if I have learned anything in my years in development it is that there usually isn’t “one big thing” that needs to be done to “solve” a problem, rather it is a matter of getting a lot of little things right. This is set against a political system that is looking for “one big thing” or “one big idea”, as if that is all that is required. If that “one big thing” fails, you are in big trouble. In contrast, if you have multiple useful but more modest activities underway, at least some of them are likely to work. Put another way, the one big project, if it fails, will fail in a big way; however, if you have multiple smaller projects, you will no doubt have some failures––but you will also have some successes within that mix! In that sense, perhaps it is a question of attempting to hedge against risk, at least as far as development is concerned.

Q: Of course, during your leadership there in Kandahar this happened, and throughout the whole twenty years there’s this ongoing debate about risk, right, and how much risk is acceptable, particularly for civilians in the field. And I think we’d be missing an opportunity if we didn’t ask you about that because of your personal experience with it. And then maybe your thoughts about it, how much risk is too much risk, and we have this conversation about Libya and other places in the world and whether we should have a fortress embassy, and no one should ever leave and how many times we can get out of the wire and all that sort of thing. So, maybe if you could start with your personal tale of, example, and we’ll take it from there.

ADDLETON: Maybe we mentioned it earlier and someone would want to verify it, to make sure this statement is accurate. But I think that in that twenty-year period of State Department involvement in Afghanistan, there were two Foreign Service officers that paid the ultimate sacrifice. One of those was Ragaei Abdelfattah, a USAID officer working in the Kunar Valley––you may remember what happened there. And the second one involved Anne Smedinghoff on a visit to Zabul in southern Afghanistan.

The first of these attacks took place in 2012, which means it occurred at about the same time I arrived in Afghanistan. The second attack was in April 2013 and that is the one that I experienced up close and personal. And I think I might have mentioned earlier, before we started this recording, that about a year later––I don’t know the exact date, but I believe it took place while I was still serving in Afghanistan––one of Ragaei Abdelfattah’s USAID colleagues committed suicide. He too was a casualty of the Afghan experience.

Following the suicide of the USAID officer who I believe was on leave from his service in Afghanistan, there was a spate of articles along the lines of “Is State taking care of its people?” No doubt all of us experienced tough situations and 2012–2013 seems to have been an especially terrible year for the Foreign Services in Afghanistan. Perhaps the end of the surge and the start of the drawdown increased the risk for all of us. I don’t remember if I prepared a “last letter” for my family or not. However, I did arrive in Afghanistan prepared for a worst-case scenario. I mean, if you don’t think about that when you volunteer to serve in a place like Afghanistan, you are not being realistic––you have to face the idea that you may indeed pay the ultimate sacrifice.

That said, when you think of the risks associated with service in Afghanistan over a twenty-year period, including the dozens of people who served in all those PRTs and DSTs, all those road trips in the countryside, all those shuttles between the embassy and Kabul Airport––it is remarkable in some sense that the civilian side of the effort in Afghanistan did not involve more casualties. More than a few contractors were killed or injured. In contrast, as far as I know the number of career Foreign Service officer names remembered on the memorial wall at State is limited to two. From time to time, I think that my name should have been the third.

We mentioned this before beginning the recording. I don’t know if you can ever recover from something like this. Of course, I will always remember what happened in Zabul on April 6, 2013 when Anne Smedinghoff was killed, and I was walking a few feet ahead of her. She had come down from the Public Affairs Office in Kabul and the plan was to meet the governor, visit a school, and deliver books.

Afterwards some people commented, “Oh, all this for a photo opportunity, was it worth it?” Of course, it is not worth it if this single event is viewed in isolation––but it wasn’t solely about a photo opportunity, either. The fact is, outreach was part of our mission in Afghanistan and like others we engaged in it all the time. I had been to Zabul previously. As for this particular trip, delivering schoolbooks was part of it but it also involved other meetings including with the governor and other motives including highlighting the importance of female education. I mean, if you are going to talk to the governor, you are going to emphasize female education among other subjects and you are going to have conversations with other key leaders as well.

In terms of what happened, I had just returned from my second R&R [rest and relaxation]––on this occasion, I had met Fiona in New Zealand and had just returned to Kandahar via Dubai. Prior to leaving on this trip, I told my colleagues that if the Zabul trip which had been mentioned previously took place, I would plan to also participate. I don’t regret having said that––because if you have responsibility for people in your area, it’s better to assume that responsibility by also being involved and accompanying them rather than observing events from a distance back at headquarters. And if that was the way I had heard about what happened on that terrible day in Zabul, I honestly think it might have been far worse.

In any case, I did join this trip. I realized that I was entering the last third––the last four months––of my time in Afghanistan. Looking back, some aspects of this trip still seem to have taken place in slow motion. It is difficult not to superimpose my later knowledge of what happened with my later interpretation of events that preceded the attack. That said, I did think that the briefing we received before walking out of the PRT was a bit too upbeat. Zabul was always considered a tough place to work and so I was somewhat surprised at the optimism. Four years earlier, a civilian anthropologist named Paula Lloyd working with the U.S. military at the Zabul PRT had been killed and I was aware of that incident––later a book was written about her, titled The Tender Soldier. As far as the upbeat assessment related to Zabul in April 2013 is concerned, colleagues assigned to such places always look for hope wherever they can find it and perhaps that is what was reflected in this particular briefing as well.

So, we stepped outside the walls of the Zabul PRT to visit a nearby school. The decision on whether a visit like this involves walking or a vehicle mostly rests with the PRT and the security detail. I don’t know if anybody else would have second guessed the plan provided by our “guardian angels” which indicated that this would be a walking event, one similar to what I understand others in the PRT had taken in the past. It was a short distance, but it was out in the open and involved crossing a road.

There was one other complicating factor––and this is the point that I don’t think I will ever completely understand––in that we went first to one door to enter the school compound where we were told by a security guard to retrace our steps and enter via another, second entry point. Looking back, this would seem to be a terrible mistake and that thought has certainly also crossed my mind. I don’t know why we were turned away. In any case, it was a short walk in the open and the school, which staff from the PRT had visited previously, was just across the road from the PRT. Although I had been to Zabul before, this was my first visit to the school. So we had our briefing, we walked across the street, we were turned away at one door to the compound and then we proceeded to walk to a second door. As I understand it, there was a small initial explosion involving an IED [improvised explosive device] hidden in a pile of pallets near the PRT wall. And then there was a second explosion, set off by a suicide bomber who drove a white sedan car into our small group.

As happens, the suicide bomber had earlier parked outside the PRT and when I stepped out of the door the driver of the car was being asked to park somewhere else. I don’t know why he didn’t explode his bomb at that point. I was literally three feet from the car. The soldiers were shooing him away, asking him to park somewhere else. So he drove around the corner and just sat there and then, when the small bomb exploded, he again came out and drove into our small group.

I was at the head of the group. I tend to walk fast, I guess, and basically the suicide vehicle went into the middle of the group. I fell into a very shallow ditch, and I basically thought, this is how my life ends. I also expected an attack on the PRT by some Taliban soldiers in the immediate aftermath of the explosion. At the same time––and I take some comfort from this––my immediate reaction was not one of fear or terror, rather it was a feeling of acceptance of what was about to happen. This is the personal aspect of experiencing something like this. I am not sure if gratifying is the right word for it. However, I am glad for my reaction. It was not fear. It was not terror. Rather, it was a feeling more along the lines of “I’ve had a great life.” I also thought of my family, which I guess is what you do in these situations. I also thought of Fiona and our kids and how they might be told.

I don’t know if it lasted for two minutes or three minutes. However, the soldiers accompanying us basically said, Okay, it is now safe, go back to the PRT. Of course, on my way back I observed everything chaotic and terrible that you can imagine. Kelly Hunt, our public affairs officer in Kandahar, was critically injured and seemingly unconscious. I briefly held her hand. Anne Smedinghoff was still alive. I held her hand also as she was carried back to the PRT in a stretcher. She was unconscious but I held her hand and said repeatedly, “You’re going to make it, you’re going to make it.”

And then we went into the safety of the PRT. I am not sure how much later it was, perhaps an hour. But someone from the PRT told me that Anne Smedinghoff had passed away. It was terrible. At that point, you are shocked, everything seems to fall apart. What happened that day is that my Afghan-American translator Nasemi, who I was close to, was killed. I had to identify him, and I could hardly recognize him. Three soldiers––Staff Sergeant Christopher Ward, Sergeant Delfin Santos, and Corporal Wilbel Robles Santos––were also killed. Five people died in those terrible few seconds.

After all this, I returned to Kandahar in a helicopter. Five of us had flown up from Kandahar earlier that day: Nasemi, Anne Smedinghoff, Kelly Hunt, and two other colleagues, one from Kandahar and another from Kabul. In contrast, I flew back to Kandahar alone. I later described it to friends as the loneliest trip I have ever taken. Put another way, I was the only one in our small group arriving that morning by helicopter that wasn’t either injured or killed within the hour. Anne had flown down from Kabul that morning. We had met on the tarmac for the first time.

Later that evening I visited Kelly in the trauma unit at Kandahar Airfield. She was unconscious and had terrible injuries. We were not sure if she would survive. I did say on my return to Kandahar that I felt I should accompany the remains of my colleagues back home, which I did.

I don’t know if you experienced it when you were in Kabul. However, in Kandahar I attended countless––dozens, for sure––ramp ceremonies involving the departure of flag-covered coffins on an airplane back to the United States. Usually, the ceremony included a hymn, a prayer, and a final farewell. So, on this particular occasion I attended another ramp ceremony, this one involving five flag-covered coffins. Only this time I boarded the plane after the ceremony had concluded, traveling in the hold with my colleagues.

First, we flew to Kabul where three more sets of remains were added to the five placed in the airplane in Kandahar, bringing the total to eight. We then headed to Dover via Frankfurt. David Snepp from the Public Affairs Office in Kabul also traveled with me. So there were two of us that traveled to Dover to meet Anne’s family. As for Nasemi, his remains were the responsibility of someone waiting at Dover from the contracting company that had hired him.

I spent twenty-four hours in Washington, was comforted by a couple of colleagues and then returned to Kandahar to finish the final four months of my tour in Afghanistan. Acting Deputy Secretary of State Burns who had been my ambassador in Jordan asked to see me, typifying his kindness and generosity. It was harder to find a senior USAID official with similar compassion though I appreciated understanding from other friends who had served in Afghanistan and knew something of what I was experiencing.

Of course, you have to live with what happened all the time, it never goes away. You second guess yourself. You imagine how a different decision might somehow have changed the universe. You wonder why I couldn’t have just said, we are not going on this trip. Realistically, though, it would have been completely out of character for me to say something like this, to have canceled this particular trip at the last moment.

I might add that every time I went out beyond the so-called wire––and I went out dozens of times––the thought always briefly crossed my mind that this might be my final trip. I mean, it is the rational thing to do in such a situation. I mention this because some people say, Did you have a premonition that might have made you say, let’s cancel this trip? Realistically, though, I can’t call what happened on this day or any other day a real “premonition.” I mean, if it was a premonition, it was a “premonition” that I experienced dozens of other times, every time I took a trip outside the wire, realizing that it could turn out to be my final one. And again, it would have been uncharacteristic of me to say, “We’re not going”; it would have been uncharacteristic of me to have the briefing and then say, “I have a bad feeling about this, let’s not take this trip after all.” And yet you do second guess yourself, imagining if only I had done “x” or “y.” Maybe I should have done that. But it is impossible to rewind the clock or replay the movie.

Parenthetically, I have to say that Anne’s family was very kind to me personally. It was hard but I am glad I met them, describing to them as best I could something of that awful day. Every April 6 Anne’s friends and family participate in a Zoom call to remember Anne and I usually participate in those conversations.

It may be worth adding here that much of the reporting in the aftermath of what happened was completely wrong. One early report said that our group had been riding in an armored vehicle; in fact, no vehicles were involved. Then Diplopundit weighed in to say that “someone” must have “ordered” Anne to leave the vehicle and walk rather than ride, adding further question marks in another story headlined, “Was this the day we almost lost another ambassador,” followed by speculation, skepticism, conjecture, and insinuation about what “actually” happened.

The reality is, you are damaged goods after something like this happens and reading a variety of misleading accounts makes it even worse. It’s awful. I mean, you can’t help but think dire thoughts about yourself and what you might consider doing to yourself. So when publications that perceive themselves as taking the “high road” and “speaking truth to power” get things badly wrong, it leaves you feeling very empty and very desolate.

Later the Chicago Tribune published a story headlined “Poor Planning leads to Diplomat’s Death.” It was based on the military after-action report and as far as I know did not involve any conversations with any civilians involved. Certainly, I was never interviewed. I saw a copy of the report and sent a critique of it to the embassy in Kabul, highlighting what I considered as several defects in the story. From my perspective, it was a CYA [cover your ass] type report and I think State colleagues agreed with that assessment. I guess the Chicago Tribune accessed the army report via a Freedom of Information request. However, as far as I know they never reached out to me as an eyewitness for another perspective. At some level, I am surprised there wasn’t more reporting about what happened.

When I retired from the Foreign Service in 2017, the investigative group ProPublica which does great work tracked me down, asking for my input on a story that they were researching. I had a long interview with one of their reporters. Looking back, it seems to me that the Chicago Tribune article implied there was a back story and the several Diplopundit accounts implied that there was a back story. As for the military report, I considered it flawed at the time. Against that backdrop, I was somehow okay with the ProPublica research––they talked to a large number of people in their effort to get to the bottom of it. I don’t want to be too defensive because I think it is appropriate that such tragedies be looked at in depth, if only to explore definitively what happened and take certain “lessons learned” from it. Yet for me it was somehow reassuring that ProPublica looked at what happened in detail and as far as I know in the end decided that the story did not need to be pursued any further.

The FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation] did talk to me shortly after the attack in Zabul, and I will say it was, from my perspective, a professional interview. They basically said that this would go into their files and if there were a case because an American had been killed, they would pursue it. They basically started the interview by saying, “You can’t blame yourself for this, the bad guys here are not you and you were not the one that did it.” So this comment basically set the stage for a series of searching questions that seemed to be different from those posed by the military investigators.

I don’t know if there was a State RSO after action report or not. If there was, I never read it. But again, as I recall, it was only the FBI guy who came down to record my version of what happened. I described blow by blow to the FBI agent what happened though perhaps at that time I was still traumatized.

Perhaps I’ve said more than needs to be said about Zabul for this oral history project. However, when you look back at that twenty-year history of State Department engagement in Afghanistan and you talk about risk assessments, this was an example of a young Foreign Service officer paying the ultimate sacrifice, which none of us hope we ever have to do. But we do voluntarily join the Foreign Service. I also think of our two adult sons, one of whom spent four years in the military and the other of whom enlisted in a particularly challenging specialty, the slogan for which is “First There.” In the Foreign Service, too, you have to be prepared for the worst, that is an essential part of the Foreign Service life. For better or for worse, I have some very idealistic views about what it means to be a Foreign Service officer. Perhaps that is why I ended up in Afghanistan. Looking back, I realize that it could very well have been my life that ended on that terrible day in Afghanistan. I regard everything that I have since experienced as an unexpected bonus. I say “bonus” but maybe that is not the right word. I no longer think about what happened at Zabul every single day. However, it still remains as a shadow that I will have to live with for the rest of my life. That is the only way I can describe it.

Q: Ambassador, thanks for sharing that with us. I just want to say first of all, thanks for your service. I know this is a hard thing to talk about. And people will put this under the microscope, of course, but I thank you for what you’ve done. And I did want to leverage back the other way. Our diplomatic security folks, they’re in a tough position, right?

ADDLETON: Yes.

Q: They have to make these decisions on a daily basis with a lot of people. The flip side of this is, you are there for a reason. You spoke earlier about the importance of having personal connections with people, and particularly in a place like Afghanistan where everything is so relationship based, and relationship focused. I encountered more on the other side of this with officers desperately trying to get out of the wire so that they could talk to people and engage with people. And these are simply, there’s a value to that that simply can’t be done through the internet, can’t be done remotely. If it could be, it’d be done in Washington, right? So, I wondered if you would opine on that a little bit and maybe just explain to folks that don’t have the in-country experience, the value of getting out of the wire and engaging with folks personally. And all over the world, but I think especially in Afghanistan, right?

ADDLETON: Yes, I appreciate those comments and I have a couple of quick things to say about that. It’s interesting that the CG [consul general] here in Lahore comes from a security background and spent time in Afghanistan, and he’s a wonderful guy. To my mind, he is a larger-than-life figure. He’s from Hawaii. He looks like a sumo wrestler, has his hair in a bun, and wears Pakistani clothes. He is also very popular in Lahore. He’s the kind of person that is very good at establishing relationships and making those personal contacts that you mention. And I’ll sing his praises here––his name is William Makaneole. And he’s just a great representative of the United States in Pakistan. Of course, Pakistan is also a very tough place to work and there are certain security precautions. But he does get out and talk to people and the relationships that he established really do matter for our diplomacy efforts in a hard country.

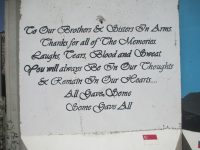

With respect to Afghanistan, I think the State Department had an agreement with the military under which the military assumed responsibility for State Department security in a war zone. So the individual trips that we took in Afghanistan did not require prior RSO approval though we did have RSOs in Kandahar who liaised with the military––they talked to them and they talked to the embassy in Kabul as well. The security for the trip to Zabul was handled by the military, not the RSO. And, of course, I will never forget the security that the military provided to us throughout my assignment in Kandahar and I will never forget our three “guardian angels” who were killed that day. I later visited the memorial garden at Fort Stewart near Savannah where they are also remembered along with dozens of their comrades who also lost their lives in Afghanistan. I have great respect for them.

Thinking about security issues more broadly, it helps to have someone like the CG here in Lahore who himself comes from a security background yet sees the need for outreach and understands the importance of outreach, even if it involves a certain amount of risk. In Pakistan, as in Afghanistan, you have to have your eyes wide open. And yet you also have to recognize that the dynamic now is different than six or eight years ago, even if a certain amount of risk remains. Of course, a lot of these conversations take place back in Washington. And, when you hear the word “Pakistan” in Washington, certain “alarm bells” tend to go off. Still, it is nice to have someone like Will in today’s Foreign Service.

In terms of personal contacts during my Kandahar assignment, I was surprised at how many conversations I had with locals. You want to think that those conversations made a difference. As I mentioned, the main messages that I was attempting to convey from Kabul was, first, that we are working to strengthen the central government in Kabul and, second, that ISAF is a diminishing presence that will soon entirely disappear. Added to this list was a third priority of my own, to not appear as a mindless bureaucratic functioning at a sort of command-and-control level but to more humanize and personalize it, somehow connecting at that level as well. And, looking back, I do think that I had some meaningful conversation in which something along these lines actually happened.

I wonder about some of the Afghans I interacted with, especially because the Taliban are now in control. I know about some of them. For example, the deputy mayor of Kandahar who I interacted with from time to time who was also a poet was later killed in an IED explosion. Among other things, we talked about Malala who was killed in a battle against the British during the nineteenth century at Maiwand, not far from Kandahar. For a time, we actually had a DST in Maiwand and I remember flying by helicopter over the site of the battlefield. While the British had the upper hand in the beginning, they were later soundly defeated.

All this happened on what was supposed to be Malala’s wedding day. Her fiancé was in the Afghan Army. When the Afghans were on the verge of defeat, Malala reportedly ripped off her veil, waved it like a flag and rallied the troops before she herself was killed in battle. Her name resonates in Afghan folk songs, and she is a national heroine, somewhat like Joan of Arc. This happened in 1880 and to this day families sometimes name their daughter Malala in honor of her.

Against this backdrop, Malala of Swat emerged on the Pakistan side of the border as a compelling proponent for female education. Her father, a Pushtun nationalist with a progressive bent, later said that he named his daughter Malala because he wanted her to be brave and courageous, like the original Malala of Maiwand. While I was in Kandahar the international media reported on the attack on Malala’s life in Swat, precipitated by the Pakistan version of the Taliban. Somehow, she survived, further expanding her platform for making the case for female education. Eventually, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her work.

Against this backdrop, I wrote an article titled, “The Two Malalas,” basically drawing parallels between the two with respect to their courage, bravery, and commitment to making a difference. My Pashtun translator loved it. We were going to place it in the local Pashtun press, thinking it would resonate in southern Afghanistan where Malala of Maiwand was a hero. However, in keeping with protocol we first had to send it to Kabul for approval––which in turn sent it to Washington for clearance, clearance that in the end was denied. Someone shared with me the cable from Washington which essentially said, “Please no more Malala.”