Known as the ‘Giant of Africa,’ Nigeria stretches across the continent like a patchwork quilt, sewn together from dozens of historically independent religious, ethnic and linguistic subgroups, all vying for political representation and control. After achieving independence in 1960, the infant nation struggled to maintain a fragile peace as members of the Muslim Hausa-Fulani ethnic group dominated the North and Christian-Animist Igbo and Yarubo divided the resource-rich South.

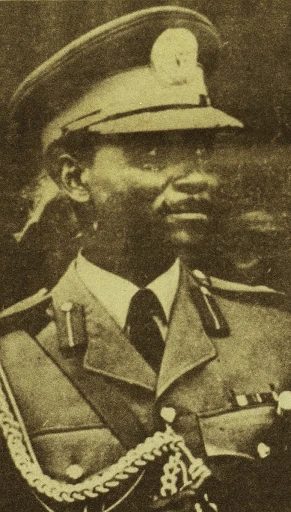

Then in 1966, a series of military coups resulted in the execution of Nigeria’s political leaders and the rise of a new government ruled by the northern military leader, Supreme Commander Yakubu Gowon.

The coup incited months of rioting and reprisals as northern fighters targeted Igbo army officers and roving mobs slaughtered tens of thousands of Igbo civilians. Those Igbo who survived fled to their former homes in the southeast, carrying tales of governmental violence and betrayal with them.

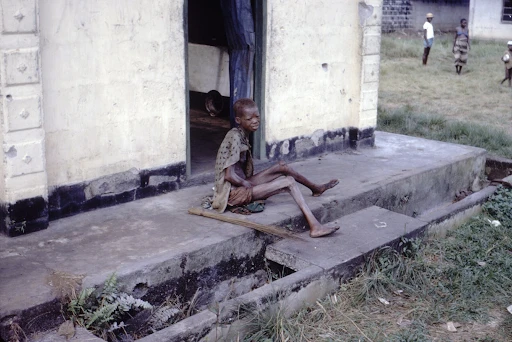

In response to the massacres, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu established an independent Republic of Biafra for the Igbo people on May 30th, 1967. War began on the 6th of June and lasted three bloody years, sparking a massive humanitarian crisis as thousands of Nigerians starved to death or perished from preventable diseases.

The tragedy sparked international outrage and an outpouring of concern. In the following interview with Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning February 1993, William Haven North, who was serving as the Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Director for Central and West Africa Affairs, describes the logistical hurdles he had to overcome as AID frantically responded to the crisis.

“The most extraordinary outcry”

NORTH: When I returned to Washington in the summer of 1966, the civil war had just started and was beginning to build up. The relief crisis was becoming a major issue. There was the major foreign policy question of defining the strategy of how we maintained our relationships with the Nigerian Federal government and Biafra….

Biafra had declared its “independence” in May 1967 following months of negotiations aimed at resolving the dispute. Americans including many USAID personnel were evacuated from Enugu [capital of Biafra] in October 1967.

The first appeal for relief was announced in November 1967 by the Nigerian Red Cross with a committee to coordinate the work of voluntary agencies and in December 1967, USAID authorized Catholic Relief Service to make the first allocation of food assistance. From that time on until the early months of 1970, the disruption of masses of people in the Eastern Region grew in scale and intensity as a consequence of the Federal Government’s blockade of Biafra and the gradual military encirclement and squeezing of the Biafran territory by Federal troops.

And with this disruption came the most extraordinary outcry in Europe and the U.S. to provide relief to those, particularly within Biafra, who were suffering and dying from famine and disease. I don’t believe there has been anything quite like the breadth and depth of feeling about a crisis of this kind before or since….

The Biafrans had been very effective in getting a public relations group to tell their story. This was one of the first times we had anything of that kind on television other than Vietnam. There were great fears about famine and possible genocide. Both the facts about the numbers at risk as could be determined and the propaganda distortions stimulated a massive pressure to do something. The public sympathies were largely with the Biafrans, although the U.S. Government policy initially was more supportive of the Nigerian Federal Government.

Over this period, essentially from 1966-70, I experienced four years of probably the most frantic and intense pressures one can experience. While I was involved from the outset, I was appointed USAID’s coordinator of relief operations with a working group of specialists in food assistance, health, logistics, and legal matters.

This took place in November 1968 when the USAID disaster assistance office reached the limits of its resources and legal mandate (disasters were only to last 60 days at that time and rehabilitation 90 days). My job was to coordinate in Washington the full range of relief activities for both sides of the conflict funded by USAID and liaise with the State Department and private groups.

“Only a cease-fire will halt the starvation of an estimated 5-6 million in Biafra”

In October 1968, I, along with Stephen Tripp, USAID Disaster Relief Coordinator, and Ed Marks, USAID Coordinator in London and subsequently in Nigeria, traveled throughout the federally held territory in the Eastern Region (we were not allowed to enter Biafra) to survey relief requirements…. We prepared a lengthy report on the conditions in the war area, the requirements for food and other aid, and alternative logistic plans, particularly addressing the question of deliveries within Biafra.

We also prepared a brief report addressed to Assistant Secretary Palmer which he could use in his meeting with General Gowon [Head of the Federal Military Government in Nigeria, 1966-1975, at right] in an effort to persuade Gowon about the seriousness of the relief needs in the area.

It was a carefully balanced presentation of some graphic descriptions of the desperate circumstances of starving people (which Gowon claimed could not be true) with a positive tone about some improvements resulting from Government relief efforts (so as not to offend government sensitivities).

The aim was to increase Federal Government cooperation in addressing the humanitarian crisis in the area and restrain the excesses of military operations….

In November 1968 following this review of the relief situation, my working group and I prepared a report to the Assistant Administrator for Africa and Assistant Secretary of State for Africa. I recommended “a reexamination of the overall approach to the Nigerian dilemma. Nothing short of a cease-fire and negotiations with both sides giving higher priority to human well-being will halt the worsening starvation and tragedy for an estimated 5-6 million in Biafra and about 2 million in Federal areas.”

Initially under President Johnson the U.S. policy had been “one Nigeria.” We would not support any attempt to split up the country. Then Nixon became President in 1969 and the word “one Nigeria” was dropped.

Because of the tremendous public support for Biafra, U. S. policy became more ambivalent about Biafra’s secession and the principle of “one Nigeria” and the uncertainties about the outcome of the war. I believe that Nixon was somewhat partial to the Ibos [also known as Igbos] but largely wanted to do whatever was necessary “to get the issue off my back.”

At the request of Kissinger (then National Security Advisor to the President), the State Department was asked to prepare an NSSM [National Security Strategy Memorandum] for the President and Cabinet on the future policy of the U.S. towards Nigeria and the relief crisis….The main theme of the NSSM was that our primary interest and objective for Nigeria/Biafra was humanitarian.

The Memorandum laid out U.S. national interests, alternative policy objectives with pros and cons, the relief requirements, and the alternative ways in which emergency aid could be provided. It was clear to me that the volume of food alone that was required was far beyond any logistical arrangement that would be feasible without a cease-fire and direct access to the Biafran area….

“How many are starving? How many are dying?”

Of course we were not involved militarily at that time. The U.S. policy was not to provide any military assistance to the Federal government, which made the Nigerian Government angry because it sounded like we were not supporting them….

But, of course, we were not supplying the Biafrans either. We were attempting to find ways to restrict the arms flow, but I learned from this experience how extensive the worldwide black market in arms was and how difficult to control. Our interest was humanitarian and every effort we made was aimed at minimizing the humanitarian crisis.

Of course, you can rarely separate the humanitarian from the political. [O]ne of the Senators, Senator [Charles] Goodell [D-NY], visited Biafra and adopted a Biafran baby as a show of compassion and political zeal. At the time, I didn’t think it was right for the baby. The Ibo people were attractive and effective. The emotional support for Biafra was extraordinary.

Q: Africa’s borders are very arbitrary, but any readjustment is an absolute nightmare.

NORTH: That is right. That was a major policy issue, and like Vietnam and other places, the precedent as a concern that secession might have created a domino effect throughout the continent, as some believed. The issue of supporting Biafra was also tied up with the question of oil interests; the major art of the oil reserves in Nigeria were in the Eastern Region with substantial American oil company investments.

Were our interests in these oil resources better protected by supporting Biafran secession or the preservation of Nigeria as one country? As I noted earlier, U.S. policy became somewhat ambiguous on this point.

The Biafran relief operation became more difficult to address as the area was increasingly circled and compressed. As a consequence, there were constant pressures for information: How many people are there, how many are starving, how many dying, what were the food requirements, how much food was available locally?

This numbers game persisted throughout the four years of the emergency. Public and political leaders always wanted to know how many were starving and how many were dying. In a situation like this, there are the real facts, which are extremely difficult to determine, and the political “facts” promoted by those interested in under- or overestimating the numbers. There were claims of 14 million people at risk and in need of food; others such as our intelligence community reported that those numbers were grossly exaggerated claiming only about one million were at risk.

So we were constantly faced with people who were very genuinely concerned but overly influenced by one side of the issue or the other on the scale of the need. The major concern was trying to convince the Federal Government that there was a serious problem of starvation and a potentially massive death resulting from the war.

There were innumerable tensions among the relief agencies and with the Federal Government. The Federal Government would complain that these “do-gooders” were coming in and taking over and telling them to get out of the way. “After all this is our country; what are you doing here?” It was a very, very tense situation….

“Whether it did any good or not, I don’t know”

As the war began to move against Biafra in 1969 and Biafra began to shrink in size and collapse, the international hysteria reached new levels of concern about the potential for genocide, that the Federal troops would go in and wipe out the Ibo people.

We had to do something to stop them. We had to respond to the Federal Government in a way that would prevent this from happening. We knew by December 1969 that the collapse was imminent; something needed to be done; so new contingency plans were developed. (We were always doing contingency plans.)

Then in January 1970, it became quite clear that the crisis was coming to a head; we needed to respond in a major way to the Federal Government to demonstrate

that we were supporting the relief effort, helping them as a way of moderating this fear that there would be genocide (A fear that was exaggerated and not borne out, in fact, although it has been estimated that a million people lost their lives from the time of the earliest riots in the North.)

At the same time, the Federal Government had been meeting with the USAID Director Mike Adler laying out its needs and taking advantage of the domestic pressures in the U.S. to do something. Mike Adler was at the one end of the phone and cable traffic and I at the other. He went to the government and they said that they wanted this, this, and this, etc. And the demands grew bigger and bigger with “we wants”…

80 more 5-ton trucks, 400 generators of all kinds, 10,000 blankets, 10,000 lanterns, nearly complete power stations, etc. Of course, the word was getting out through the system to the White House that these requests were coming in: “How are you responding? Have you got it done? How are you going to get it there?”

Meanwhile, I had been in the process of locating 80 or so 5-ton trucks, blankets, lanterns, generators. I learned very quickly you don’t buy 5-ton trucks ready to go. They have to be assembled. You buy a chassis here and a body there, etc…. Kissinger had joined in the act because the Nigerians were making such a point about the need for trucks[and] the word came down: “Give them what they want.” I found that he was calling up truck companies as well.

In the process, UNICEF said, “Well, we have a dozen trucks that you can have.” But they didn’t tell me they were unassembled and all in boxes in pieces. I could see them being delivered in Lagos in parts and somebody thinking, “Well, what do I do now? How do I put these things together?”

But we said we would take them. Meanwhile, we contacted people all over the country who said, “Well, we have a couple of 5-ton trucks here that we have ready to give to our customers. They have already been bought, but you can have them if you want them. For the cause we are willing to do this.” So we had a number of trucks volunteered, but they were all over the U.S.

Then International Harvester said, “Well, we have 20 5-ton chassis in Pennsylvania, stake bodies in Texas, tarpaulins elsewhere, etc. If we can get these together why you can have them.”

I said, “Okay, we will take them.” We arranged a deal with Chrysler, through Dr. Hannah, the [USAID] Administrator, who called the president of Chrysler motors, who agreed to set up an assembly line for us in Pennsylvania. We had the truck components come from all over the country to this place where they assembled them, including the UNICEF trucks.

Meanwhile the Air Force arrangement was stirring and the word was out that we had to get all these supplies to Nigeria in the next ten days so we had to get going. The Air Force was saying, still furious, “We are ready, where are you? Where is the stuff?” I said that it was all over the country….

So we arranged with all the suppliers to deliver to Air Force bases throughout the country….Meanwhile, the trucks were coming off the assembly line at three a day just as fast as we were getting flights off to carry the equipment….

And within two weeks we delivered 63 trucks (more by sea), 10,000 blankets, 10,000 lanterns, 400 hundred generators, etc. from all over the country on 21 C-141 sorties — USAID was charged $750,000 by MATS [Military Air Transport Service]. Large quantities of food and medical supplies had already been delivered sometime before; the problem was to get more of it.

It was an extraordinary operation. Whether it did any good or not, whether the equipment was used effectively or not, I don’t know, but it made the political statement of our responsiveness to the requests and, perhaps, tempered the Nigerian Government’s actions against the Biafrans. That was the crest of the crisis.