On August 13, 1961, Berlin woke up to a shock: the East German Army had begun construction on the infamous Berlin Wall. The Wall was initially constructed in the middle of Berlin, and expanded over the following months. It entirely cut off West Berlin from the surrounding East Germany, prohibiting East Germans to pass into West Germany. However, American military cars were sometimes able to pass through and, in the words of Charles K. Johnson, “poke around.” The Wall would quickly become a symbol of the Cold War and separated families for a generation. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan demanded “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Two years later, the Wall officially fell, leading to the eventual reunification of East and West Berlin.

Robert Lochner, who was interviewed by G. Lewis Schmidt in October 1991, was the Director of RIAS (Broadcasting in the American Sector) in Berlin. Charles K. Johnson, an Economic Officer in Berlin, was interviewed by Jay P. Moffat in 2000. Elizabeth Ann Brown was a Political Officer in Bonn when the Wall began construction. She was interviewed by Thomas J. Dunnigan beginning in May of 1995. Bruce A. Flatin served in West Berlin from 1964-1969; he was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy, beginning in January 1993.

Read another account of the building of the Berlin Wall. Go here to read about JFK’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech and the negotiations behind the Berlin Crisis.

“You are all sitting in a mousetrap now”

JOHNSON: When I first went to Berlin it was possible, occasionally, to obtain Soviet visas to travel into East Germany. Very soon after we arrived there, my wife and I went to Leipzig to a Leipzig fair. The only other place we were ever able to get documentation from the Soviets for was Potsdam. This was really very close to the border with West Berlin. I think sometime in the second year I was there, a part of their policy to turn more authority over to the East Germans, the Soviets told us they would no longer issue visas for any travel whatsoever in East Germany. We would have to get permission from the East Germans, which of course we could not accept. That ended our travel in East Germany.

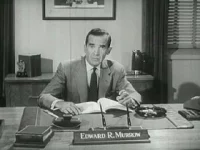

LOCHNER: Ed Murrow’s [famous American journalist who was appointed to head the USIA in January 1961] arrival in West Berlin late in the evening of August 12, 1961 was taken then and is still taken today by many Berlin politicians and media representatives as proof that the United States knew about the Wall going up. This played a big role in Berlin at the time because Germans would have felt even more betrayed if they had been convinced that the U.S. knew about it and did nothing about it. I would, of course, protest to my contacts that it was pure coincidence that Ed Murrow arrived a few hours before the Wall went up. That he was due on a routine inspection trip of what was after all the biggest overseas installation of the U.S. Information Agency [USIA].

Since he had arrived very late I did not get home until ten minutes to twelve and was just undressing when on the direct phone I had to RIAS [Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor, Broadcasting in the American Sector]. I was alerted at one minute past midnight that the East Berlin radio, which of course RIAS monitored, had started to announce, not the wall as such, but that communications within the city were cut.

Within fifteen minutes I was down at the station as were all of my American colleagues and leading German staff. We immediately changed the program, in fact the announcer had done so after the RIAS midnight news, to serious music. We carried news every 15 minutes also. And three times during the night I went over to East Berlin because my Germans, of course, couldn’t go. It was a very warm summer night, but because we didn’t know what reception we would get I hid a tape recorder under a coat. There was nothing heroic about it; at worst they would have turned us back too. I was going in a State Department car and as they didn’t that first night try to control any papers, when they saw the license plate they waved us through. So three times during the night I went and simply drove around and recorded on tape what was going on, i.e., reported from the Eastern side and it was broadcast.

Through the open window we could hear press hammers tearing up the street and see the construction crew members, each with a soldier with a gun behind him to prevent him from defecting, tearing up the street and laying these rolls of barbed wire. On the other side, one yard away — West Berlin — hundreds, if not thousands, frustrated West Berliners shouting their outrage and demanding that the wire be removed. We could hear such shouts clearly and I translated some of them for Ed Murrow. That was a very discouraging situation to be in.

The most unforgettable and depressing sight was on the third trip about 10 in the morning. I got out of the car for the first time at Friedrichstrasse Station, which later became the cross over point both for Germans and foreigners who did not enter by car, and the vast waiting hall was full of thousands of people milling around with desperate faces, cardboard boxes, some with suitcases.

On the staircase leading up to the elevator train, the black-shirted Trapos, Transport police, who vaguely reminded me of the SS, they had virtually the same uniforms, stood locked elbow to elbow blocking access to the staircase going up. As I was standing there observing the scene, a pitiful old woman timidly walked up to one of them, they were standing about three steps up, and asked when was the next train due for West Berlin.

I will never forget the sneering tone in which the guy answered: “That is all over — you are all sitting in a mousetrap now.”

“To have confronted the Communists could have brought about some type of hostilities”

BROWN: Well, the Wall went up on a Sunday morning. On Sunday afternoon in Bad Godesberg there was a tournament of Little League baseball teams in Europe, which everyone was watching. In the course of the games word came to the…Ambassador about the Berlin Wall, which at that point had been under construction for some hours. The CBS correspondent in Bonn came up and told the Ambassador.

It turned out that an officer from the Legal Office of the Embassy had been duty officer. He had gone into the Embassy and looked at the telegram from the U. S. Mission in Berlin, reporting that the Wall was going up. He wrote, “Noted” on the telegram and never said a word to anyone about it.

FLATIN: You have to remember that the Berlin Wall was constructed by the Communists largely upon their own territory — in fact, some meters back in many places. So in order to confront them over this, would mean that we would have to actually get Allied forces involved in stopping East German troops who were covered by tanks and machine guns, from building a structure on Soviet-occupied territory. It wasn’t as if they were building it on our side of the boundary.

They continued to permit the Western Allies access to the Soviet sector. Our insistence was that this was one city, Greater Berlin, and we should have free access to the Soviet sector. This goes back, incidentally, to what I said about the difference between sector and zone. We could go freely into the Soviet sector of Greater Berlin, but we could not go freely into the Soviet zone that surrounded us.

Indeed, the Soviets also observed this difference. People who lived in the Soviet sector of Berlin had a different type of ID card in those days from the ones who lived in GDR proper. And indeed the members of the Volkskammer [Parliament] from East Berlin had more limited voting rights in the Volkskammer than the other people from the GDR, such as residents of Leipzig, would have. Representatives, who went from Western Berlin to the Bundestag down in Bonn, didn’t have full voting rights either. We Allies did not regard the Western sectors of Berlin as a state of the Federal Republic of Germany, as the Germans themselves believed it to be.

JOHNSON: I had moved from the Economic Section and was working in the Eastern Affairs Section where I was reporting on East German developments. We tried to go over to East Berlin as frequently as possible just to size up living conditions and clues to Communist policy. East Berlin was a fascinating place and a small microcosm of East Germany. It contained the historic center of Berlin. It also was so large it contained considerable farmland within its city limits. We would visit East Berlin in our private cars bearing U.S. military plates and look into things, poke around in the stores and see what was on the shelves to size up how the economy was doing. It wasn’t doing very well. That was always a problem for the East German government.

FLATIN: To have confronted the Communists again over this important act of deciding to build the barriers could have conceivably brought about some type of hostilities that I don’t think Kennedy would have wanted to risk. It’s something that was tough for Kennedy to bear, but I don’t see any prudent way that he could have gotten around it.

If we had been denied access into the Soviet sector, if American jeeps were not permitted to go in there, then we would have had more of a legal complaint than we had with their putting up barriers which, in essence, were to keep East Germans from getting out of their own “country.” (When I use the term “barriers,” incidentally, it reflects the fact that there was a masonry wall only in the downtown urban area of the city; the remainder of Western Berlin was surrounded by a triple line of barbed wire fences — with razor sharp concertina wire in between.)

Berlin’s barriers were matched by barriers going down further west between the two Germanies. And this was a very cruel type of boundary, and it created a sort of prison for the people on the eastern side. It divided families…You just can’t cut through a nation like that and not have blood relatives on both sides of the line.

LOCHNER: Innumerable families were separated that day and in some cases it took years before with Red Cross intervention they were reunited. I have never seen as large a group of miserable human beings as these thousands of people. Most of them had not heard the radio and came to the station thinking they were taking the train to West Berlin.

JOHNSON: It was unfortunate because we were reporting on a country we couldn’t enter. All we could do was go over into East Berlin. Of course we read their press voluminously. That was one of the daily challenges: to wade through 10 pages of “Neues Deutschland” every morning.

We began to have a few problems getting across the border toward the end of my stay there — that is, sector-sector border in the center of Berlin. As part of their efforts to turn things over, the Soviets would occasionally authorize East German sector border guards to stop us and ask for our papers. Our instructions were to deal only with Soviet soldiers.

There were maybe nine sector-sector crossing points at that time and sometimes my wife and I would go to the opera in East Berlin at night and it would be dark coming back so you had to go slowly as you crossed over so they could read your license. There was not any formal checkpoint like what Checkpoint Charlie was to become a year later. There was simply a group of East German guards standing out in front of Brandenburg Gate and you had to slow down for them. Sometimes they would make you stop and we would point to our license plate. They would play dumb and say, “Well, I need to see your papers.” And we would say, “Oh, no, you don’t and if you have any problem with this just call the Soviets about it.” Which they never did. This was just a curtain raiser of a much bigger problem that came up after I left Berlin.

LOCHNER: Later on we found that among these desperate people milling around there were innumerable cases where so as not to make it too obvious, say, a father and daughter had taken a train — that is all it took at the time to defect — on Saturday and mother and son were due to follow on Sunday. Innumerable families were separated that day and in some cases it took years before with Red Cross intervention they were reunited. I have never seen as large a group of miserable human beings as these thousands of people. Most of them had not heard the radio and came to the station thinking they were taking the train to West Berlin.

All during the night; we were the only station on live all night long at that time. Most German radio stations carried canned news during the night and so many West German stations didn’t carry the news of the Wall until their first live news in the morning, say at 6 am. Of course we carried live news every 15 minutes in the hope then that it might still help some people to escape. It turned out that the cutting of the city in half was so effective a measure that they started breaking up the streets simultaneously at all the points where later the Wall was constructed.