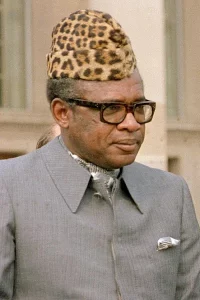

Born to a modest family, Joseph-Desiré Mobutu prospered in the Force Publique, the army of the Belgian Congo. Mobutu became army chief of staff following a coup against Patrice Lumumba, and after a second coup on November 25, 1965 assumed power as military dictator and president. He changed the Congo’s name to the Republic of Zaire and his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko.

Leader of Zaire’s sole party, the Popular Movement of the Revolution, Mobutu’s anti-communist stance won him Western support and the funds to combat opponents in adjacent countries. He nationalized the economy by pushing foreign investors out, only to let them back in when the economy began to fail. As president of Zaire, Mobutu was famous for corruption and nepotism while the people of Zaire suffered from poverty and human rights abuses. He embezzled an estimated $4-15 billion during his time in office. His three-decade regime came to an end in May 1997 when rebel forces threw him out of the country.

In an interview with Charles Stuart Kennedy in February 2004, Jacob Gillespie recalled his time as a Field Operations Officer in the Republic of Congo during Mobutu’s coup. Kennedy also interviewed Dan Zachary, economic officer in the 1960’s in July 1989, and former Ambassador to Zaire Walter Cutler in September 1989. Kennedy also spoke to Michael Boorstein, a personnel officer, in September 2005. Thomas Stern interviewed former Ambassador to Zaire Brandon Grove in November 1994.

Please follow the links to read more about Africa, dictators, and states struggling to organize politically in the wake of colonial rule.

“The Congo learned that the military isn’t really equipped to manage most of governing”

Jacob Gillespie, Field Operations Officer, Leopoldville (Kinshasa), Republic of Congo, 1964-1966

GILLESPIE: …The next event of importance, while I was there, was the coup. At that time, Joseph Desiré Mobutu, later Mobutu Sese Seko, took over the country. It was Thanksgiving 1965.

Joseph Kasavubu, the President, had named Moise Tshombe Prime Minister (seen left) the year before. This was probably good internally for the country because Tshombe brought the Katanga support into the country finally, but it was terrible internationally.

The other Africans and Europeans had a very hard time supporting Tshombe at all. He had led Katanga’s post-independence separation bringing the United Nations in and leading to a war. He was a fairly good leader, compared to the political leaders in the Congo, which had no real national political leadership. He was as good if not better than most but it wasn’t good enough.

…Mobutu took over and during the time I was there, I think it was a positive change. I was only there for another year and his corruption was not yet fully evident. There are a number of things in governing that a military can do and they do them rather well; things that demand order and precision and some control. The military does that fairly well.

The Congo learned, as other countries have learned, that the military isn’t really equipped at all to manage most of governing. They aren’t great economists; they aren’t by trade, doctors or health care specialists; and so this sort of thing falls to the side and that happened too, later on. But I think that first six months probably was rather positive, although during that time, as I said earlier, the Mobutu-Godley (United States Ambassador to the Republic of Congo) relationship fell apart…

“When the US is the most crucial supporter of the regime you do not PNG the American Ambassador!”

Dan Zachary, Economic Officer, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 1966-1968

ZACHARY: During my two-year tour, the most severe economic crisis was Mobutu’s decision in December 1966 to seize the holdings of the huge Belgian mining company, the Union Miniere de Haut Congo or UMHK (seen right). The largest holding of this firm were the copper and cobalt deposits in Katanga Province, but they had other holdings as well. Since mining operations were the principal source of the country’s foreign exchange earnings, his grab was an immediate threat to the country’s economic stability.

The Embassy played a critical role in moving this unwise action toward a solution. The Belgian managers were ousted and replaced with Congolese directors. The firm’s name also was changed to ‘Gecomines’. Mobutu was pressured to hire the former managers back to run the operation and production levels began moving up. A layer of enriched friends of Mobutu were put in place. However, the negative economic impact was not permanent.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey made an official visit to the Congo in January 1968 with a large official party. It was quite a show and a payoff for Mobutu’s solid cooperation on Cold War issues…

Within a week of arrival, I learned that Mobutu decided to PNG (declare persona non grata) our ambassador, [George McMurtrie] Mac Godley (seen left). He was told to depart immediately, within a day or two. This, of course, caused great consternation in the front office and in Washington.

To deal with the situation we later learned that the CIA Station Chief, Larry Devlin, went to see Mobutu. Larry had been in country for some time and knew Mobutu well. Whether true or not, it was generally assumed that the CIA had engineered Mobutu’s rise to power.

Larry reportedly laid it on the line: When the US is the most crucial supporter of the regime you do not PNG the American Ambassador! As a result of this intervention, so the story goes, it was agreed that Godley would be allowed to stay for several weeks and that a new ambassador would be assigned…

“Why don’t you lean on some other countries, particularly ones that are not as friendly as I am?”

Walter Cutler, Ambassador, Kinshasa, Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo), 1975-1979

CUTLER: [Mobutu] is very, very well informed. He starts his day with Voice of America. As a matter of fact, I learned that very quickly. I learned that I had to start my day early with Voice of America, because if there was something on the air that was of interest to the President or of concern to him, my phone was going to ring at 7:15 in the morning. (Mobutu is seen right.)

It was very difficult keeping ahead of Mobutu with respect to developments in our own country. He has a very, very strong interest in media. He was a reporter once himself, before becoming President.

And it was very evident in the case of our presidential elections of 1976 that he had followed them closely enough so he knew very well that if Carter were elected, human rights was going to become much more of a center-stage issue than it had been before.

It was not much of a surprise that I showed up on his doorstep after the election, talking about human rights. It was good that he was already aware of this because it made my job a little easier…

Mobutu, of course, didn’t think it was necessary and he didn’t think it was well- advised. He would sometimes humor me about this new-found obsession with human rights.

He would say, “Look at all the problems I have out here, what do you expect of me? Why don’t you lean on some other countries, particularly ones that are not as friendly as I am? Why don’t you concentrate on them?”

I remember at that time we were not having a very good time with Algeria. He picked something out of the press about human rights violations in Algeria and wondered why we hadn’t addressed that problem in a more vociferous way, as we had with him.

He would sort of make light of it sometimes, but there was no question that our points were getting across, because he kept referring to human rights, even though sometimes in a fairly joking way.

But it was on his mind, it was very much on his mind. And that was good, because he knew that we cared, and that he couldn’t go on doing certain things without our taking notice and perhaps factoring it in to our own approach to his needs.

“Mobutu basically kicked out a lot of those people.”

Michael Boorstein, personnel officer, Kinshasa, Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo), 1974-1977

BOORSTEIN: … [Mobutu Sese Seko] decided that to consolidate his power he had to show that foreign commercial interests were no longer welcome. The country was able to fend for itself without the presence of the Indians, the Pakistanis, and the Lebanese, primarily.

They basically were running the small businesses in the country. They were the shopkeepers, hotel clerks, and ran the restaurants. There were a few Italian and French restaurants, but a lot of the commercial infrastructure was run by Pakistanis and Lebanese.

The Lebanese were primarily Jews. The little hotel that we ran through the commissary association was known as the Alhadeff Arms (the flat-roofed building on right in photo at left) because Mr. Alhadeff was a Lebanese Jew, who came to the former Belgian Congo years and years ago and his family was still involved there. Mobutu basically kicked out a lot of those people.

Well, the country went to hell in a hand basket economically. The crime rate skyrocketed. People were hungry in the countryside, starting to come into the big cities including Kinshasa, and they were living by robbing the white people. That’s when we got the 24-hour presence in the house, our post differential rate went up, and then eventually Mobutu saw the error of his ways and invited the people to come back…

“Democratic institutions and respect for human rights had no place in his schemes.”

Brandon Grove Jr., Ambassador to Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo), 1984-1987

GROVE: …Proud, vain and thin-skinned, Mobutu was obsessively concerned about imagined slights to his presidency. If one understood this sensitivity, made clear one was talking about issues, and not demeaning the dignity of his office, Mobutu would usually listen carefully, and the dialogue could deal with some of the most contentious aspects of US-Zairean relations. We would quite often, for example, be able to discuss such topics as transparency in financial transactions, human rights, and political reforms.

In the end, I was instrumental in causing several political prisoners to be freed. Mobutu created a government office for human rights during my tour, making a big point of it with me when it was opened.

Occasionally, I would call on the head of that office, Citizen Nimi, who was one of Mobutu’s henchmen. I did not get the impression that this citizen felt passionately about the rights of his fellow citizens.

I attempted to make progress on issues of economic and political reforms by appealing to Mobutu’s sense of history. I asked him how he thought history would judge him if he did not take steps toward reform, suggesting that such measures, were he to apply them, would be applauded. “Think of your place in history!” I implored him, with scant expectation that I could persuade him to act in accord with our policy objectives and his own best interests.

In fact, Mobutu cared little for the people of Zaire. He was never interested in discussing our economic aid programs with me. Military assistance was a different matter. Despite his skill at raising money, Mobutu did almost nothing to provide schools and functioning hospitals, roads, water, sanitation, electricity, housing, or anything else for the ordinary Zairians, who created an extended-family economic system to stay alive.

He enjoyed his power over them, and their organized support at staged mass rallies. Democratic institutions and respect for human rights had no place in his schemes. Mobutu felt, himself, accountable to no one.