Nine days after David Sprague arrived in Pakistan to work for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), a plane crash killed President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq and American Ambassador Arnold Raphel. Three months later, in December 1988, Benazir Bhutto became the prime minister–and the first female to lead a democratic government in a Muslim majority country. Bhutto’s support for girls’ education coincided with USAID’s desire to expand its Pakistan program. With strong Washington support, USAID Pakistan launched an ambitious program that contributed to a 70% increase in girls’ enrollment in two conservative provinces bordering Afghanistan. The program was halted six years later when the Pressler Amendment forced a cutoff in aid in response to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program.

U.S. President George H.W. Bush invited Bhutto to a state visit in June 1989. The National Security Council and White House aides pushed hard for policy initiatives to support the Bhutto government — and provide “deliverables” for the state visit. Pakistan had struggled for decades to improve its education program. By 1988 Pakistan was in the midst of its seventh five year plan, which still failed to reach target goals for literacy and enrollment rates. USAID quickly developed a primary education program that concentrated on Balochistan and the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), with a particular focus on increasing the number of girls in school.

David Sprague began his career with USAID in 1972, as a civil servant in the Office of Education. Already a leader in the education sector, Sprague transferred to USAID’s Foreign Service in 1988 and assigned as an Education Officer in Pakistan. He stayed for five years. He later served in Ukraine and Bangladesh. After retiring from USAID in 2001, he was an education consultant to USAID and the World Bank.

David Sprague’s interview was conducted by Ann Van Dusen on February 5, 2018.

Read David Sprague’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Mary Claire Simone.

Excerpts:

“We started to work on a major primary education program immediately when I arrived. There was no precedent for it.”

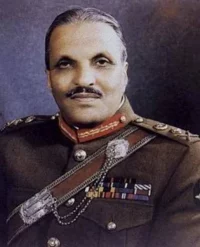

New Prime Minister, New Emphasis on Education: Nine days after we arrived was the plane crash that killed General Zia (Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq) and the (U.S.) ambassador, Arnie (Arnold) Raphel [on August 17, 1988]. I think it took more than three months before Benazir Bhutto became the new prime minister. There was a great deal of enthusiasm and anticipation. Benazir had gone to school in the U.S. and was immediately looked upon as someone favorable to the West.

Serendipitously, the politics of trying to establish a large USAID education sector presence in Pakistan, with a new leader in Benazir, led us to accelerate the project development. It turned out she was going to visit the U.S. soon . . . a state visit with [George H.W.] Bush. The White House wanted to have documents to sign. We put through during the next, I think, three months, development of a project in [Balochistan and the North-West Frontier (NWFP)] provinces to the tune of $280 million dollars over 10 years…. And it was signed in the White House during her visit. I have never seen anything that big move so fast, and it was purely because the U.S. wanted to have something in the social sectors signed at the time she was visiting. But it really launched us in those two provinces.

“The emphasis from the beginning was, how could we get more girls into school?”

Prioritizing Girls’ Basic Education: [T]his was a time when, for AID, basic education was the priority . . . The emphasis from the beginning was, how could we get more girls into school? . . . When we started in Balochistan, only three percent of school age girls were in school. It was by far the poorest province, and one that was lagging the most. The NWFP was a little bit better but still, as far as girls’ enrollment was concerned, it was bleak . . . By far, the major issue was that you had to have female teachers if you were going to try to get more females in school. You had to be able to get the schools close enough to where the girls were living, so the parents felt safe. You had to convince the parents this was worth doing, to have their daughters go to school. I was surprised at how receptive both the people in the province and the girls themselves were to come and be involved . . . There certainly was [resistance] in the beginning with the fathers. They kept saying, “It’s not safe. It’s not safe. They will be attacked.” We would have meetings with these groups of men, and they would say those things. I would say, “Who are you talking about? Aren’t you talking about yourselves?”

“The program resulted in more than 2,100 new girls’ schools in two provinces, a 70 percent increase.”

A 70% Increase in Girls’ Enrollment–Before the Program Ended: [A published evaluation concluded,] “The program resulted in more than 2,100 new girls’ schools in two provinces, a 70 percent increase.” It ran from 1989 to 1994. The reason it stopped was that the U.S. government was under the strictures of the Pressler Amendment and the U.S. president had to certify every year that the Pakistanis were not building a [nuclear] bomb. The president had certified that every year when Pakistan was assisting us in fighting in Afghanistan against the Soviets. But then after the Soviets left Afghanistan he did not certify, so the aid program was stopped. . . . I really believe that if we could have stayed for the 10 years, we could have accomplished something that would have had the chance of becoming permanent.

. . . “I’ve not heard of another education project in AID that has been that large, nor that developed as rapidly as that one did . . . In the two provinces, there were 348,000 girls enrolled in Grades 1-5 in 1989. In 1996, that number was 761,000, so it almost doubled the number of girls in school. Boys’ enrollment increased from 1.3 million to 1.6 million. As I told the mission director, Jim Norris, “I would do this job even if you didn’t pay me. I had the chance to design what I wanted, I had the resources I wanted, and the people to do it.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Classical Studies, St. Louis University

MA in Speech and Drama, St. Louis University

Church Degree (Licentiate of Philosophy), St. Louis University

USAID Civil Service Career

USAID Office of Education 1972-1988

USAID Foreign Service Career

USAID Pakistan 1988-1993

USAID Ukraine 1994-1997

USAID Bangladesh 1997-2000

Education Consultant 2000-2015

World Bank/USAID Consultant in Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan

US Based: Academy for Educational Development, University Research Center, USAID/India, Adjunct Professor at SAIS and Georgetown University