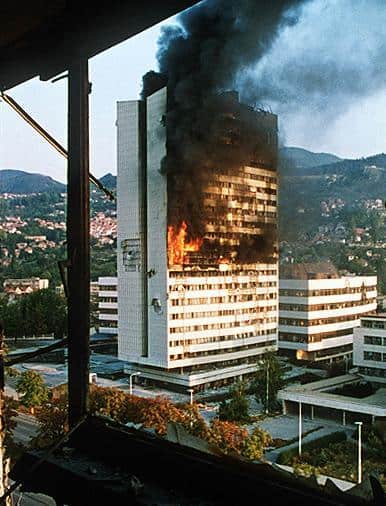

Bosnia, 1995: utterly decimated infrastructure, near-universal unemployment, and a state bank straight out of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Such were the conditions when USAID officer Craig Buck arrived in country to put together a reconstruction program in the aftermath of the Bosnian War. Recognizing the severity of the situation, Buck worked at lightning speed to get a sweeping U.S. aid program up and running long before the UN response was even underway. With the resolute backing of Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, the architect of the Dayton Accords, Buck leveraged aid to successfully marginalize hardliners within the Republika Srprska and bring about their compliance with the agreement. Meanwhile, Buck’s pursuit of a massive reconstruction program coupled with major reforms enabled the Bosnian economy to recover rapidly.

Craig Buck was born in Jackson, Mississippi and grew up in Carthage, Texas. He attended Texas A&M University from 1962-1966, where he majored in Government. He then took a year-long research scholarship in Bolivia, followed by another year attending graduate school at Stanford, before joining USAID in 1969.

Craig Buck’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on August 3rd, 2017.

Read Craig Buck’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Dylan Miles

Excerpts:

“…something that is a normal 18-month process within AID, we did in about three weeks.”

BUCK: Yes. I’ll give AID credit. While I had problems institutionally, there were a number of individuals who understood the priority and the urgency of what we did. So, on the economic side, to get a contractor to work on the banking system, and credit to private companies, and generate employment, we developed a project and put it together – something that is a normal 18-month process within AID, we did in about three weeks. We put it together, and got our contract office to recognize the need for limiting competition, and we had a contractor on the ground, and we made our first loan, I believe, by the 1st of June of the following year. So, we went from our analysis and actually had everything, basically, in about three months’ time. Similarly, on the reconstruction side we recognized the need for a rapid infrastructure rehabilitation program to get the electricity, water, road, bridges, markets facilities, and power generation and transmission stations up and running quickly to get the economy moving. Again, just using good judgment about what would make sense and with the support of many radicals in Washington we were able to move the system and have a project for $184 million signed with Bosnia, a contractor on the ground, and projects underway in less than four months. To avoid audit problems we built a concurrent USAID audit function into the program that USAID’s Inspectors said after about a year that our controls and integrity was so effective there was no further need for them to audit on a day to day basis. This activity was critical to getting fundamental infrastructure facilities back into operation quickly, to help address personal resettlement problems, or provide the resources fundamental to economic recovery.

“…there’s no excuse for holding back.”

BUCK: I think a lot of that is due to some of the individuals in Washington who understood that Brian Atwood, who considered himself to be the Bosnia desk officer, said, “I want something to happen, and there’s no excuse for holding back.” So, the normal analysis that you do, the justifications that you do, we did not do. We did what, to me, was intuitively obvious. We’re professionals, and we think we know what probably makes sense. And, in the end the activities we initiated had enormous impact on Bosnia’s economic resuscitation, something we short-circuited by months or even years just by moving forward on what most would agree were the highest priorities. But in all honesty, AID did not have a post-conflict capacity. AID was accustomed to working in developing countries, and was not accustomed to rapid post-crisis response. What do you do when you have a war, and you have an economy that is destroyed?

BUCK: ….we were there on the ground and working long before the UN had its organization set up. We were out making loans or, for example, in the other areas where we were working, we were way ahead, before they had their personnel on the ground. We were rehabilitating war-damaged infrastructure while the UN experts were still looking for their own housing and perquisites. However, we did make it a point that we would coordinate and work with them, that this was an international effort. We were one part of this effort – we obviously had our own particular interest, but we were all part of a broader international effort. On the economic sphere, the Special Representative quickly set up a weekly economic council, and the participants were the European Bank, UN (United Nations), World Bank, IMF, and USAID. We were all working together on the same broad economic policy basis. Similarly, the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) was responsible for the democratization side of things, and for elections. We seconded– AID seconded probably the best person that AID had, in terms of managing elections, to the OSCE, to help manage that process. So, you know, I guess we were all working together.

I believe another important factor to remember is that Ambassador Richard Holbrooke had authored the Dayton Peace Accord and had an enormous investment in making it successful. He came to Bosnia normally every 10-14 days after Dayton. In my first meeting with him he called me to the Presidency where he, Bosnian President Izetbegovic, the Foreign Minister, and many others were discussing immediate steps ahead. He asked me to explain what the USG would do for reconstruction, and I outlined the program I had discussed earlier with Brian Atwood. I also emphasize the conditions we would place on our assistance and the conditions they would need to meet. Holbrooke told the Bosnians to give close attention to these activities and to ensure they met conditions. He also told me that it was vital that the USG make these reconstruction efforts successful and that the United States should look good by our performance.

“We had…an effort to drive a wedge between hardliners in Pale and more responsible officials…”

We had a fairly robust program working in the Bosniak and Croat areas. But because the RS (Republika Srpska) failed to turn over war criminals, they were denying people the right to return, they were not providing evidence of war crimes, they continued to discriminate, we did not work there. However, about six months after the Dayton Accord the new president of Republika Srpska, Biljana Plavšić, began to break with the hardline – or hardliners, we called them – elements in Pale, which was the capital of the Republika Srpska at that time. She recognized, I think, that an approach of being hardline was going to isolate Republika Srpska. She began to meet with us, and so with the agreement of the ambassador, we opened up our program to Republika Srpska…. we were only working in communities that are allowing refugees or internally displaced people to return. We’re only working areas that were turning over indicted war criminals. We are not working in areas that actively promoted discrimination based upon ethnic or religious origin.

We had a fairly rapid opening to Republika Srpska, with an effort to drive a wedge between hardliners in Pale and more responsible officials who saw the need for cooperation with the West. That proved to be successful, because ultimately Krajisnić, the prime minister and the various leaders – were ultimately isolated, and Plavšić who, at great peril and being under death threats moved the Serb Government to Banja Luka. Anyhow, I think we, the United States, diplomatically and economically were able to support efforts to show that supporting the Dayton Peace Accords would bring tangible results to their communities.

“You had… an unemployment rate of probably 80 percent.”

BUCK: In both areas, but in particular in the Federation areas, economic growth returned very quickly. I mean, here, you had, when we started, an unemployment rate of probably 80 percent, where GDP had was 1/4 of what it was when the war began. We had large numbers of people that were returning. There were many refugees that had gone to Europe or neighboring states, and they were returning. But the economy began to get reactivated very quickly, and I think a large part of it has to do with the industrial sector getting going, along with the repair of war-damaged infrastructure that we were doing. The industrial sector had been fairly robust in the former Yugoslavia. They produced cars, they produced electronics, they produced a variety of goods. They were the main source of the Yugo Vehicle. We were able to get a lot of these industries running again. We attributed 25% of the GDP growth rate to the program that we had, and economic growth, as I recall, was nothing short of phenomenal. I mean, it doubled in the first year after the Peace Accord, and we had a major role in that.

“”…’Jesus, now I can really do some business.’”

As we began to open up to Republika Srpska, the economic and trading relationships that had existed before the war reopened. I’ll give NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) credit for a lot of this because they were able to enforce freedom of movement across the IEBL – the Inter-Ethnic Boundary Line – which separated Republika Srpska from the Federation. Both sides, Serb and Bosniak, viewed the IEBL as a frontier, but NATO viewed that as simply a delineation between two entities as outlined in the Dayton Accord, and therefore NATO insisted on freedom of movement across the IEBL… So, businesses quickly resumed – The Bosnians were, like the Kazakhs, quite entrepreneurial, and they saw opportunities. They said, “I can go back to my old buddy up in Banja Luka and buy what I used to get and sell it down here.” Similarly, the Serbs saw the things that they could buy and trade in the Federation areas. But one of the problems, for example, in this, was that each entity had a separate license plate. As soon as you would get across the line, they could tell, “Okay, you’re a Serb. You’re a Bosniak.” And wartime animosity could resume for some. One of the things that the UN did was to ultimately say that there would be only a unitary license plate. They decreed that that would take place. Well, of course, the uproar in Republika Srpska was that you’re destroying our independence… But, of course, now most of the entrepreneurs think, “Jesus. Now I can really do some business.”

Q: Yeah. Did you run into problems of what a typical, you know, move towards full market-driven economy, which is, you know, the scams and pyramid schemes and things like that – In other words, a bit of economic criminality, as well?

BUCK: We were heavily involved in promoting transparency in government. The third leg of our reconstruction program, besides getting credit out to private businesses and repairing war-damaged infrastructure was to get the fundamental instruments of economic governance—of the enabling environment—established. We were heavily involved in setting up a balanced and fair tax system, in making it fair, transparent, and open. Similarly, we worked on helping establish a transparent and data-based budgeting system. We had a large program to set up a banking supervision and monitoring program as well as drafting the provisions that governed the functions of a private banking regulatory system. We helped set up the Central Bank in Sarajevo as it began to function as an independent authority. We worked with it in the issuing of its new currency, when it moved from the German mark to the convertible mark, which became the currency of the realm. But we set up the regulation for the banking system so that people would have confidence in it. And, we were key to providing assistance in developing a privatization program to get rid of a lot of old enterprises that had few assets and a few former employees that needed to be moved into more productive areas.

“…you don’t have to worry about Big Brother looking over your shoulder….”

An area that we worked in that I think was a singular success was called the Payments Bureau. When Yugoslavia still existed, the Payments Bureau was a government office that functioned as a bank and as a treasury, and industries, enterprises, and individual firms, each day, would turn their income over to the Payments Bureau, which they had to make payments to through the Central Bureau, much as you would do through a bank. But the Payments Bureau had a monopoly on information, and it had a monopoly on the monetary system as well as the fiscal regime information. You paid your taxes to it, and it paid government employees through it. As a result, the government knew everything that was happening. It was a mechanism of political, as well as financial, control. It was a virtual monopoly on public and private economic transaction information and a major impediment to rapid private economic investment and exchange. For a market economy to develop, the Payments Bureau had to be abolished. We needed to have a banking system performing those functions. We needed a government treasury that was not monitoring what everybody did, but collecting and counting the amount of money coming in and putting it in the bank and making payments according to law… We worked with the Bank and the Fund to carry out a program to dismantle it, and replace it with a government treasury and with the appropriate regulatory and supervisory framework for the commercial banking system.

We had enormous opposition to the speed with which we did this from the IMF. Fund staff and the UN High Rep’s Office said it would take us 18 to 24 months to do it, and my staff and I said we’re going to do it in three. We worked with the government, and the government bought into this, and it was replaced in the time frame we recommended. It had a massive impact on transparency, and people feeling that, well, you can operate now independently. You don’t have to worry about Big Brother looking over your shoulder, monitoring everything that you did. So, that was a real success.

But it’s interesting: When the prime minister used this – He called me in one day, before we got around to dismantling the Payments Bureau, and he said, “I see that you’ve given a loan to company X. Company X is –” He didn’t say it, but we knew it was a political opponent of his. “You shouldn’t do this.” I said, “How do you know this?” He said, “The Payments Bureau. I get a daily report on it, and I know you’re doing it.” So, I could see how they were using it for their own political purposes.

Q: And yet, remarkably, you were able to convince him to let go of it and move beyond this sort of –

BUCK: I’m not certain what their motivations were. I think a lot of them had interest in the private banking system, and they saw that they could make more money there. The other thing is that they were genuinely interested in becoming part of the EU or a western nation. They recognized that this was part of being part of the international monetary system right. You didn’t have a communist relic as you moved to become part of the West. And, I think they understood that when we demanded adherence to conditionality that we would enforce it. I would have brought the overall international assistance program to a halt if I could over this if I had to.

Joined USAID 1969

Ankara, Turkey—Consular officer 1969–1972

Office of the Secretary for Narcotics Matters—Senior Advisor 1976–1978

Sarajevo, Bosnia—Mission Director 1995–1999

Pristina, Kosovo—Mission Director 1999–2001

Podgorica, Montenegro—Mission Director 2001–2002