As decolonization was embraced on the world stage, the U.S. government and its diplomats had to decide, “How do we deal with the question of Puerto Rico?”

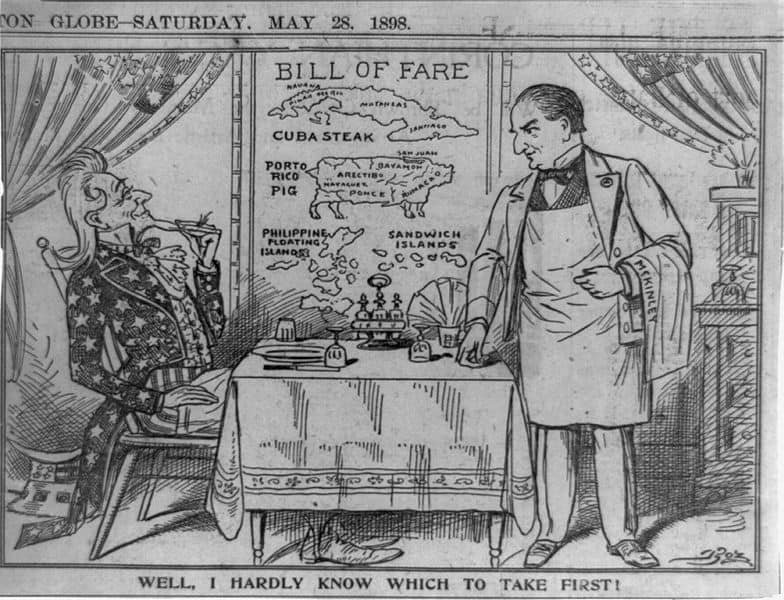

The island had been an “organized but unincorporated” American territory since the United States defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War. After negotiations between Puerto Rican political leaders and the U.S. Congress, Puerto Rico held a referendum in 1952 that established itself as a Free Associated State (Estado Libre Asociado), known as the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

While Puerto Rico was granted this local autonomy, the ambiguous language associated with the “commonwealth” status has since continued to spark political debates amongst both Puerto Rican leaders and members of the international community. The Puerto Rican nationalist movement continued during the 1960s—a time of radical political change, in which 32 countries in Africa gained independence from their European colonial rulers. These newly-independent African nations and some Latin American countries, including Cuba, attempted to support the Puerto Rican nationalist movement in world fora, to the chagrin of the U.S. government. Amidst the decolonization movement, the United States faced criticism for its continued retention of territories in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. During the latter half of the 20th century, amidst much discussion at the UN, Puerto Rico was officially declared a colony of the United States in 1978 by the UN Special Committee on Decolonization. Amongst other critiques, members of the committee—who consider the people of Puerto Rico to have their own national identity of a Caribbean nation—have referred to Puerto Rico as a “nation” in their reports.

Various U.S. Presidents have been in favor of Puerto Rican statehood, but have left the decision to the people of Puerto Rico. Voters continued to affirm commonwealth status in plebiscites, or referenda, to determine the island’s exact political designation in 1967, 1993, and 1998. Yet, support for official U.S. statehood has risen with each successive referendum, and in 2017, the majority voted for the first time in favor of official statehood. Due to low voter turnout, however, Puerto Rico still continues to struggle to define its political status.

Below is a collection of stories from U.S. diplomats who faced questions in the late 20th century from the United Nations and other countries over the status of Puerto Rico. This included U.S. efforts to prevent a formal UN visit to the island, how the State Department ended up handling Puerto Rican affairs at all, and the self-determination process of the island. It also included how Puerto Rico attempted to have its own foreign policy separate from the U.S., and how the U.S. resigned from a UN committee on decolonization when faced with international criticism.

Curtis C. Cutter was interviewed on February 3, 1992; Ambassador James R. Cheek’s interview was conducted on September 13, 2010; Ambassador Thomas J. Dodd was interviewed on May 9th, 2001; George B. High’s interview was conducted on August 26, 1993; and Frederick H. Sacksteder was interviewed on August 4, 1997. All were interviewed by oral historian and former diplomat himself, Charles Stuart Kennedy.

Drafted by Natalie Friend

“. . . the pressure on the U. S. as, really, almost the last colonial administrator, was almost unbearable at times.”

Curtis C. Cutter

United Nations Political Affairs Officer (1959-1962; 1975-1977)

Read Curtis C. Cutter’s full oral history HERE.

Q: Well, in dealing with this, did Puerto Rico get thrown in your face all day?

CUTTER: All the time. This was the time when the Cubans were very active in trying to get Puerto Rico on the agenda of the United Nations. One of our biggest activities was to fend this off. We spent an enormous amount of energy, almost as much time as we did on the China question, keeping Puerto Rico off the agenda, claiming, basically, that Puerto Rico had already had its basic act of self-determination. In fact, I think that was true. I think that was a legitimate defense.

Q: Was there ever the feeling on the Puerto Rican affair, “OKAY, fellows, you want to talk about this, go to Puerto Rico, do what you want?”

CUTTER: No. There was never that feeling. The feeling was that travel was open to Puerto Rico. Anybody that wanted to get on the airplane and fly down there could do so, and we said that. But to allow a visiting mission from the UN, an official visiting mission, to go to Puerto Rico, would be in some way to admit that the United Nations still had some say-so over our administration of Puerto Rico. We weren’t prepared in any way to admit that.

. . . .

CUTTER: Well, issues that I had to deal with, of course, were constantly recurring issues of the U. S. administration of its own, dependent areas. That was a problem that was directly in my bailiwick, for which I probably had primary responsibility in the Department. How do we deal with the question of Puerto Rico? How do we deal with the question of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands? As more and more of the colonial dependencies had become independent and joined the UN, the pressure on the U. S. as, really, almost the last colonial administrator, was almost unbearable at times. Of course, we thought that we had solved the problem of Puerto Rico by having a plebiscite there and giving them this special status, Commonwealth status. So our position always was that Puerto Rico was no longer a dependent area. It was a self-governing area, and we were no longer required to report to the United Nations about it. Our friends, the Cubans, of course, had taken this on as a major job to liberate their fellow Caribbean Latinos from the yoke of imperialism. You could count on the Cubans raising, in every forum possible at the UN, the question of Puerto Rican independence. This is one of the issues on which we always circulated people before the General Assembly, that we wanted to make sure that they didn’t buy the Cuban line on this issue, that Puerto Rico already was, in fact, self governing. Usually, we could hold the day on this issue. Usually, we could kill it in committee, but the Cubans were very persistent, and there were enough people out there, in the Third World, especially, who were in doubt, really, as to whether we had allowed the Puerto Rican people to make a free and open decision on this matter. This was an issue that we had to deal with at almost every General Assembly.

Q: Did we encourage people to go—maybe not as an official delegation, but go take a look at Puerto Rico?

CUTTER: Well, we definitely did not encourage an official delegation, because that would have been acknowledging the UN’s “right” to do this. But we always said that anybody that wants to travel to Puerto Rico is free to do so. As a matter of fact, we almost always had Puerto Ricans on our delegation to the UN, in one capacity or another, so people could go to them and hear at first hand what Puerto Rico is all about. No, we were quite willing to have anybody who wanted to, in their individual capacity, travel to Puerto Rico and take a look at what was going on.

“The ambiguity was built into the commonwealth status intentionally . . . .”

“Nobody every defined what ‘commonwealth’ means . . . .”

Ambassador James R. Cheek

Desk Officer, Caribbean Office, ARA/LA/CR (Bureau of Inter-American Affairs; AID Bureau for Latin America) (1966-1967)

Read Ambassador James R. Cheek’s full oral history HERE.

CHEEK: I was the desk officer for, well, I had all the Caribbean. I had Barbados, the Leewards, the Windwards, even had the British Virgin Islands and to make good, they also threw Puerto Rico in there.

Q: How could you have Puerto Rico? It belonged to us.

CHEEK: There apparently was no place else in the U.S. government that wanted it and, of course, at that time the Puerto Ricans were very active. They were getting themselves invited to inter-American meetings as a separate entity from the U.S. delegation so there were all these issues related to the fact that there is a U.S. delegation at this inter-American meeting but there is a Puerto Rican delegation there and also the commonwealth vote on continuing statehood was coming up. So I ended up having to do it because somebody in the government had to deal with them. They just couldn’t find anyplace else to put it.

. . . .

Q: I would have thought the Department of Interior or somebody would have had that.

CHEEK: That’s what we thought but then they weren’t a state, they weren’t a colony. Nobody every defined what ‘commonwealth’ means and there was never an agreed pigeonhole to put Puerto Rico. So, I had these weird states. The Brits had given these states; they had severed the tie with all these. They called them in and said, “Look, we want to get out of here. We want to get out of the colony business” — with the notable exception of Bermuda which they kept and still have today. “We are going to give you a golden handshake,” and then sort of pushed them out the door toward the United States because they were all money losers for the Brits. You couldn’t make any money; in fact, you had to subsidize most of the islands. The British assumption seemed to be, “If you guys were independent or semi-independent, the United States would be your sponsor and they’d give you all this aid money.”

We were, of course, furious with this. Dean Rusk was Secretary. The whole concept of mini-states just drove him up the wall.

. . . .

Q: In Puerto Rico from time to time there were resolutions promoting Puerto Rican independence in the UN. Did you get involved in any of that stuff?

CHEEK: I ended up having to be the action officer for this portfolio and then having to take the lead. I remember two issues; one, there was a vote coming up on independence and then there was this big issue of what to do about the Puerto Ricans turning up with their own delegation, a separate delegation in these meetings. How did we handle that and how did we treat them?

I did get a trip to Puerto Rico out of it, which was real nice although I couldn’t say I was

the desk officer for Puerto Rico. I was just the responsible officer for Puerto Rico. Whenever we tried to pursue a legal definition because there was no agreed law or agreed definition of ‘commonwealth status’ and what it was or wasn’t, we just sort of got along. We just lived with that. The ambiguity was built into the commonwealth status intentionally and neither side wanted to push this to a definitive definition, so you just had to be very imaginative.

I can remember going around having to get clearances and walk papers around and people looking at me. Sometimes Interior would get involved because there would be issues touching on its equities. The lawyers would always be involved. That made it very interesting. As I say, I got my trip, one trip. I was warned not to do anything that treated them like they were independent, but it was fun.

“Do you want independence, do you want statehood? Do you want to continue the commonwealth status?”

Ambassador Thomas J. Dodd

Ambassador, Uruguay (1993-1997)

Read Ambassador Thomas J. Dodd’s full oral history HERE.

Q: What about Puerto Rico? Sometimes this is an issue of Latin Americans who say, “Oh, you should free Puerto Rico, or whatever you’re doing.” We keep holding referendums. The Puerto Ricans don’t want to leave, but you get beaten up on it.

DODD: I was asked frequently about Puerto Rico. My response was, what has happened in Puerto Rico is that through several plebiscites, referendums, Puerto Ricans chose the Commonwealth status, or a free associated state. I said that throughout its history—or I should say really since the 1940s under Muñoz Marin—they’ve had elections and in some cases plebiscites and referendums. “Do you want independence, do you want statehood? Do you want to continue the commonwealth status?” They have chosen that direction. So I said, “We’ve always been basically open in the sense [of] choose what you want. We have not dictated the commonwealth status. If they want to be independent, that’s their business.” Stu, maybe I wasn’t all that persuasive with student groups and faculty members, but I never got much criticism back, because when I threw it back in a sense in their laps by saying, “The Puerto Ricans choose the form of government they want. They have a representative in Congress that cannot vote in the House but they can vote in committees,” and I said, “That was a step forward, and because they wanted it and we accepted it, so they can move to a voting representative in the Congress if they make that choice of statehood.

“In a way, it had its own foreign policy. I know that at times actions by the government in Washington annoyed Puerto Ricans; at times the shoe was on the other foot.”

George B. High

ARA-Caribbean Affairs (1973-1975)

Read George B. High’s full oral history HERE.

But the Caribbean was still very much of a stepchild. Nobody really paid much attention to it unless there happened to be a crisis. . . . It was hard to get people’s attention.

There was some concern that some of the small, newly independent islands would be taken over by gangsters and drug traffickers, because they were so small and their institutions so fragile. It really wouldn’t take a lot of money to buy people out and cause difficulties. That was mentioned from time to time as a reason for paying attention to the region, but nobody took it seriously. It was just hard to get people’s attention.

One of the areas we focused on, which has been an occasional frustration for the Caribbean affairs office, was Puerto Rico. It was an American territory (commonwealth), not a foreign land. Yet it was a factor in the Caribbean and from time to time it sought to play its own role there. It projects itself as something distinctive from the United States. It occasionally sought separate representation at regional meetings. It participated, as it does today, in international games as Puerto Rico, not as part of the United States.

I was informally the designated-person in the office to deal with Puerto Rican issues. At one point I spent three or four days there meeting with some Puerto Rican officials to discuss regional matters and to listen to Puerto Rican views. I was our contact person with the Commonwealth Office here in Washington.

The government in Puerto Rico was led at the time by the Commonwealth Party. Governor Fernandes Colon featured Puerto Rico as a doorway for the United States to go out into the Caribbean and down into Latin America because it was Spanish speaking. So the Puerto Rican government had relationships with some of the Central American countries, with Venezuela, with others in the Caribbean, to project its self-image and the interests of Puerto Rico. In a way, it had its own foreign policy. I know that at times actions by the government in Washington annoyed Puerto Ricans; at times the shoe was on the other foot.

It was an interesting relationship. Mexico, for example, has always questioned what it saw as a colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico. It had some of its own ties with the island. I don’t think this had any ulterior motive particularly, but simply to say, “This is a depressed Hispanic community living under American colonialism. We ought to feel close and akin to the island.” Yet, Mexico, Venezuela, none of these other countries would think of using Puerto Rico as an avenue to the government in Washington. They had their own direct relationships with Washington and weren’t about to disrupt them. What Puerto Rico seemed to be after, a special status as an intermediary, was probably unattainable. Yet clearly it was important to the Puerto Ricans to have positive relations with their neighbors, and they had some success in this.

“We had to convince the Department that we should resign from this committee, which served only as a platform for vituperation . . . .”

Frederick H. Sacksteder

Advisor for Political/Security Affairs at the U.S. Mission to the UN (1969-1972)

Read Frederick H. Sacksteder’s full oral history HERE.

SACKSTEDER: Decolonization had really ended, by that time, but the Sixth Committee, the committee on decolonization, was a platform for some of the more extreme third world countries to lambaste colonialism as an institution and as the precursor of all the problems that developed in Africa and in other parts of the world. Max Finger and I finally concluded that we had to convince the Department that we should resign from this committee, which served only as a platform for vituperation on the part of certain elements that were trying to make a name for themselves. As you know, everything that is said in the United Nations is transcribed and then made available. While it may never appear anywhere in the United States, it gets banner headlines in certain third world countries. This is where these individuals start their political careers. . . . After about a year-and-a-half of going along with the committee’s calling meetings in order to lambaste the United States on its colonial past or colonialism including domestic colonialism—for example, how we had exterminated the native Indians and so on and so forth. We recommended, and the Department finally agreed, that we resign from the committee. Some of our Western allies were quite ready to do the same thing and did. I don’t remember exactly who did and who didn’t, but that took the wind out of the sails of these representatives who used it as a platform, because they no longer had anybody to beat on. It didn’t in any way affect the work at the UN because the world had already been de-colonized.

Coming to the question of Puerto Rico, probably the most important issue for the Cubans was to introduce a resolution on American colonialism in Puerto Rico. Having responsibility for the Latin American area, I was asked to work closely with the government of Puerto Rico in attempting to defuse this Cuban effort. Sometimes we were successful, sometimes not quite. The governor of Puerto Rico at that time was Luis Ferré, who was the leading member of the party favoring statehood. I was asked on several occasions to travel to San Juan to meet with the governor and his friends and to encourage these friends to become lobbyists for the Puerto Rican position that this was no business of the United Nations.