While U.S. politics can be contentious, American elections themselves tend to run smoothly. Usually, voters cast their ballots, numbers are counted, and the winners are declared. In many countries, the United States is seen as an exemplary role-model for conducting democratic elections, and U.S.-based groups often help run and oversee elections in other countries.

However, the U.S. presidential election of 2000 was not so smooth, causing the U.S. Embassy in Honduras’ “Celebration of Democracy” night to take an unexpected turn. A year later, Honduras itself held an election which passed without any major glitches or issues. This unusual reversal of roles was an interesting and humorous facet of Frank Almaguer’s ambassadorship in Honduras. As he said, “The Honduran media had a great time with this story. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling, one cartoon had me holding a newspaper with a headline (in Spanish) that read, ‘U.S. Election Decided in 36 Days,’ and a Honduran holding another newspaper that said, ‘Honduran Election Decided in Two Hours.’ Many of my political friends were enjoying the opportunity to suggest that Honduras would be glad to offer the U.S. technical assistance in conducting elections!”

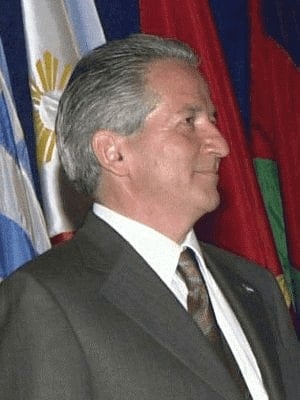

Apart from his ambassadorship in Honduras, Frank Almaguer also held positions in Belize, Panama, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Washington, D.C.

Frank Almaguer’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on January 23, 2004.

Read Almaguer’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Ashley Young

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“The public mood was becoming skeptical that democracy would lead to positive changes in their lives.”

Election Challenges: One of the big highlights of my time in Honduras was the election in November 2001. Even though this was the fifth democratic election in Honduras since 1981, when the last military regime left office, it was not as easy as that. First, there were a number of legal technicalities…. Second, there was in Honduras in 2001, and you see it all over Latin America today, a sense of “So what?” I think many voters were saying to themselves and even publicly, “Look, we’ve already been through four cycles of democratic elections, and my kids are still not going to a good school, and after the fifth or sixth grade they can’t even go to school because there are no middle or secondary schools nearby. The public hospitals are in shambles, and all I see is the politicians getting richer and the poor continue to be left out.” These voters also lived with higher crime rates, higher cost of living, and unfulfilled promises of better roads and more reliable access to water and electricity, In other words, the public mood was becoming skeptical that democracy would lead to positive changes in their lives.

“Both would today be seen as center or even center-right parties.”

Political Parties: Honduras has multiple political parties, but for most of the 20th century two parties have dominated the political landscape. The Liberals and the Nationalists. Their origins went back to the 19th century. While in the early days these two parties reflected ideological differences, by the mid-20th century in Honduras, the two parties had few ideological distinctions. Both would today be seen as center or even center-right parties. Their appeal tended to be based on family political affiliation (e.g., “If my family was Liberal then I am a Liberal.”) or whom you knew on either side. Both parties relied heavily on patronage (e.g., government jobs and contracts) to get out the vote. In Honduras, presidents are limited to one four-year term with no possibility of re-election. The incumbent, Roberto Flores, was a Liberal and his predecessor had also been a Liberal. The Nationalists were convinced that 2001 was their year to win back the presidency.

Nationalist Candidate: The Nationalist candidate, Ricardo Maduro Joest, was a successful, well-to-do businessman who was U.S.-trained and very well disposed to the U.S. His views were closely aligned to those of U.S. President Bush and they shared friends from the business community. The fact that the Nationalists had aligned themselves with the Conservative Union, an international grouping of like-minded parties, including the Republicans and the British Conservative Party, helped to create a positive view of the Nationalists within the Bush Administration. Maduro was well known to us and was a frequent visitor at the Embassy and Residence events. As a former Central Bank president, he earned a great deal of respect among bankers and economists in the region. A big tragedy in his life—the assassination of his adult son in 1997 in a kidnapping for ransom gone badly—added to his appeal among those most concerned about rising crime. Becoming the nominee of his party seemed natural—but only after a long legal battle. Maduro was born in Panama and derived his claim to Honduran citizenship from his mother. The opposition took this to court, arguing that Maduro was not eligible to run for the presidency. In fact, during his party’s primaries he had a “stand-in” (his close friend Luis Cosenza, who won the primary with over 80% of the votes) while the matter was being adjudicated. The decision in his favor required mediation from Brazilian jurists tapped to help unlock a deadlocked Honduran Supreme Court. When he was cleared to run, Cosenza stepped down as the surrogate and Maduro’s road to the presidency was cleared.

Liberal Candidate: The Liberals were clearly divided and in the end, through a primary process, chose a lackluster candidate, Rafael Pineda Ponce. Pineda was an aging party patriarch who was serving at the time as president of the Congress. His provincial background and limited exposure to the complex economic issues of the times made him a very weak candidate. Even the incumbent, while giving pro forma endorsement to his party’s candidate, did not do much to support him. Privately, President Flores maintained lines of communication with Maduro and more than likely voted for him. The bottom-line was that it was a mismatch. At one point I invited both of the major candidates to come to the Residence, separately, to meet with a visiting CODEL who shared an interest in the political landscape of the region. Both candidates were peppered with similar questions, which Maduro handled beautifully and Pineda flubbed in a big way, unable to articulate coherent views on economic issues.

“What we wanted above all was free and fair elections and the acceptance by all parties of the results.”

Favoritism?: During that election cycle, I personally spent a great deal of time with the political parties and their leadership. In addition to the two major parties, there were three other parties running for both the presidency and legislative seats. One of the tools I used was to invite each of the parties’ leaders to attend, at separate times, working lunches at the Residence to get to know them and to reiterate to each that the U.S. did not endorse or favor anyone. What we wanted above all was free and fair elections and the acceptance by all parties of the results. This was not easy to convey since everyone understood that Maduro’s worldview was closer to that of the U.S., but everyone appreciated being given the attention they received from us. In fact, the Democratic Left Party leadership (the closest Honduras came to having a Marxist-oriented group) were particularly pleased that we were willing to listen to them. These lunch events were ideal for the reports we submitted to the Department.

Election Day: Q. How did Election Day go?

ALMAGUER: It was a very peaceful election. International observers from the OAS [Organization of American States], the Carter Center, the National Democratic Institute and the International Republican Institute, among others, were very pleased with the process. Several members of the embassy community, including staff and spouses, and I joined the observation teams, monitoring events throughout the day. By 8 p.m. that night, the defeated candidate, Pineda Ponce, went on television to accept his defeat. I tried to visit with him that night to congratulate him on his magnanimous concession but he would not see me. I think that to this day he believes that his candidacy could not get off the ground because the U.S. allegedly favored his opponent.

“President-elect Maduro… took almost an hour of his time to reiterate his interest in working closely with the U.S. on all issues of common interest.”

Diplomacy: By 10 p.m. that night, with the victory rally behind him, the political counselor (FSO Paco Palmieri) and I went to visit with President-elect Maduro, who graciously took almost an hour of his time to reiterate his interest in working closely with the U.S. on all issues of common interest. As early as that night, we agreed on a process that would bring members of my Country Team to his Transition Headquarters over a period of days to review in detail issues of U.S. interest, such as the USAID portfolio of projects, counternarcotics cooperation, military-to-military engagements and so on. This first meeting with Maduro as president-elect was followed two or three days later by a congratulatory call from President Bush, as I recounted earlier, and the latter’s invitation for Maduro to visit Washington in December. It was an excellent beginning of a fruitful relationship.

“It was a memorable event in Honduras… the event did not turn out as expected.”

U.S. Election: Q. This recounting of Election Night in Honduras reminds me that only a year earlier the U.S. had an election that took a while to resolve. How did that election play out in Honduras?

ALMAGUER: Yes, it was a memorable event in Honduras, and, I suspect, around the world. As U.S. embassies traditionally do, we organized an Election Night 2000 party at the Ballroom of the Hotel Maya in Tegucigalpa for a “Celebration of Democracy.” We invited hundreds of our contacts, including most of the political leadership of the country, student leaders, labor organizers and many other groups. We had TV monitors everywhere giving the U.S. networks’ results as they were being tabulated. The local TV stations would frequently break into their regularly-scheduled programs to cover the events at the Honduras Maya Hotel. At 7:30 p.m. that night, in welcoming our guests, I announced that the party would go on until a winner was declared in the U.S. elections. [Laughter.] As you can well imagine, the event did not turn out as expected. At 2 a.m., we invited our guests to go home….

36 Days Later…: Over the next 36 days I was a frequent visitor to the morning TV and radio talk shows, trying to explain and update what was going on. Most Hondurans had no knowledge of the Electoral College and had a difficult time understanding how a candidate with a lead of 500,000 popular votes could be involved in a legal battle over the results. I am so glad I was a good student of history and of elections since the longer this impasse lasted the more of that history that I had to recount in my talks, including why the U.S. Founding Fathers opted for this system and the meaning of Federalism. The Honduran media had a great time with this story. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling, one cartoon had me holding a newspaper with a headline (in Spanish) that read, “U.S. Election Decided in 36 Days,” and a Honduran holding another newspaper that said, “Honduran Election Decided in Two Hours.” Many of my political friends were enjoying the opportunity to suggest that Honduras would be glad to offer the U.S. technical assistance in conducting elections!

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, University of Florida 1963–1967

MA in Public Administration, George Washington University 1970–1974

Joined the Foreign Service 1973

Tegucigalpa, Honduras—Peace Corps Country Director 1976–1979

Panama City, Panama—USAID Deputy Mission Director 1979–1983

Quito, Ecuador—USAID Mission Director 1986–1990

Tegucigalpa, Honduras—Ambassador 1999–2002