A U.S. army tank manned by a defecting soldier crashed straight through a Berlin Wall checkpoint manned by Russian troops. Anxious American and West Germans soldiers hastily acted to contain the situation.In situations like these, and throughout the tensions of the Cold War, Americans in Berlin played an important part in the dynamics of Berlin.

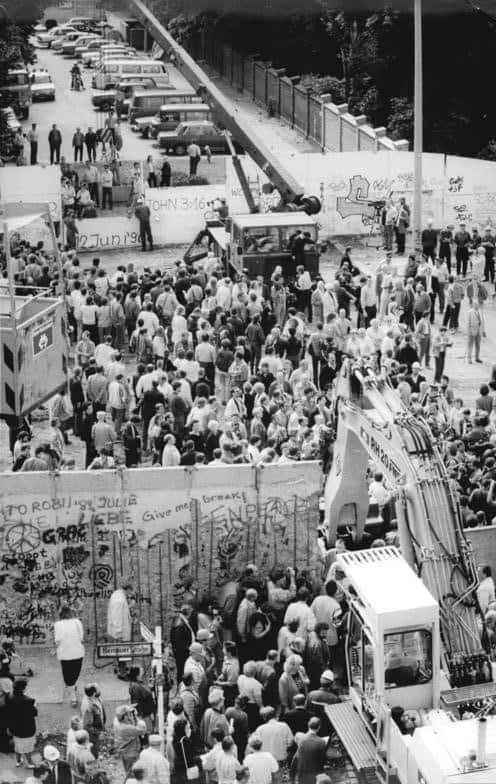

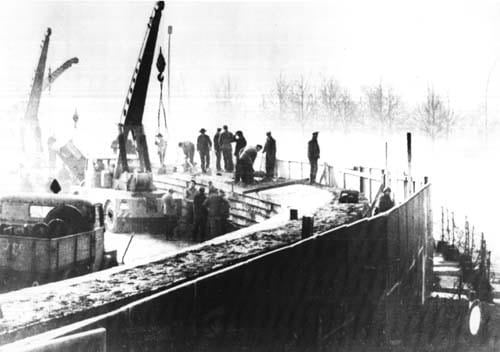

On the night of August 13th, 1961, East German soldiers began laying down the first barbed wire and bricks of what would become the Berlin Wall. The Berlin Wall was an important symbol of the “Iron Curtain” between the Western allies, West Germany (FRG), and the Soviets in East Germany (GDR) in the midst of the Cold War from 1961 to 1989. Thousands of East Germans attempted to cross at great personal risk, after many were separated from their families and cut off from friends.

Throughout the chaos in Berlin, Americans were caught up in the action. Even before the Wall’s construction, tensions over immigration and control between the Soviet, American, British, and French zones of occupation caused trouble. The following excerpts present astonishing and often perilous stories from U.S. Foreign Service Officers—from missing children passport issues to kidnapping and a plane hijacking. For Americans in Berlin, the consequences of separation were felt deeply.

Drafted by Wendy Erickson.

Excerpts:

Albert Stoffel

Berlin, Germany—Economic Officer (1950-1955)

Bonn, Germany—Civil Air Attaché (1963-1967)

Read Albert Stoffel’s full oral history HERE.

“. . . that secretary and her mother had been kidnapped from West Berlin, through a ruse by a young man who had persuaded her to give him English lessons.”

STOFFEL: There was one thing that has repercussions to this day. It occurred two weeks after I left Berlin, in the summer of 1955 to be transferred to Embassy Paris. . . . In the Berlin Eastern Element on the economic side, which I was responsible for, we had an American contingent. . . . The American staff, of course, handled classified material. On a separate floor we had a German operation where the staff followed newspapers, kept clippings, and wrote reports of various kinds, none of them classified. I had a good German secretary, who was bilingual in German and English, and therefore very useful.

A male member of that German part of Eastern Element came to visit me in Paris at the Embassy. He had come as a tourist to Paris. He wanted to tell me that two weeks after I left Berlin, that secretary and her mother had been kidnapped from West Berlin, through a ruse by a young man who had persuaded her to give him English lessons.

When the English lessons had progressed to a certain point, he said that he would like to repay her, to show his appreciation for what she’d done. So he invited her and her mother to dinner. They got into a taxicab, which he had provided. As he drove away said, “My God, I forgot my billfold, we’ve got to stop at my house and get it.” They didn’t think much of it, but they did think something was wrong when they suddenly found themselves racing for a gate between Berlin and the Soviet zone. Without their stopping, the gate was raised and in they went to East Germany.

“They wanted her to spy and she was smart enough to eventually go along with them.”

There they were interrogated by the East German secret police and Miss Trapp was asked to spy on our office. They told her they knew I had left two weeks earlier, to indicate how much they knew about what went on there. They wanted her to spy and she was smart enough to eventually go along with them. But she said, “You realize this isn’t going to work unless I show up for work tomorrow morning.” They said, “All right, we’ll fix it so that you can do that but if you double cross us, we’ll get you.” So she came back to work the next morning and immediately reported to her boss and then to the security officer.

Eventually this was publicized because it was related to another attempt where there was an attempt made on one of the German RIAS employees [Radio in the American Sector]. U.S. authorities finally decided that maybe these people would be safer if they publicized these attempts.

——————————

Robert Livingston

Bonn, Germany—Political Officer (1968-1970)

Read Robert Livingston’s full oral history HERE.

“. . . I said, ‘Put that damn passport back.’”

In theory and, I think, in international law, [Berlin] was still under occupation status. We rather emphasized that because we also emphasized, against the facts on the ground, that this was a four-power city and that, even though there was a wall, we had access—we being the American occupying authority—to East Berlin on the basis of so-called four-power rights, and we did not have to deal with the East Germans. One of the sort of hang-ups, big hang-ups, was, “Do not have any dealings with the East Germans.” That would tend to undermine this four-power, I wouldn’t say fiction, but certainly only a de facto status.

And I remember riding over to East Berlin with the then ambassador. . . We were riding over to East Berlin with George McGhee and his wife and daughter in their limousine and the East German guard came up to us and McGhee pulled out his passport, and I said, “Put that damn passport back.”

. . .

Q: Did you ever have to be concerned about being set up?

LIVINGSTON: Well, I was a little nervous about that, but one’s attitude was, “If you’re going to get in trouble, don’t talk to an East German, demand a Russian.” There were a number of people before me who, if not cowboy-like, were at least daring fellows. One had a girlfriend in Warsaw, who in effect did what he wanted to do. He’d drive down to Warsaw from Berlin through the GDR [German Democratic Republic: East Germany].

Q: Were you allowed to do that?

LIVINGSTON: No, theoretically not, and I guess he was showing his passport to the East Germans.

—————————–

Janice Bay

Bonn, Germany—Economic Minister, Acting Deputy Chief of Mission 1994–1997

Read Janice Bay’s full oral history HERE.

“So, they took the body, and they held the body, and it took us around two weeks before we eventually got that body back.”

And so we were responsible for essentially eastern Germany, and if anything happened to any Americans in eastern Germany, we had to figure out what to do. And a lot of things happened to Americans in eastern Germany. . . . Most Americans that visited eastern Germany were either elderly Americans of naturalized Americans who came from pre-WWII Germany. Because they were retired they were allowed to return for family visits. There were also American church groups who visited eastern Germany. I can give you a few examples of the things that happened.

. . . I was really being watched in Berlin because everybody watched everybody. In an occupied four power city, the British listened to the telephone conversations of the Americans and the Americans listened to the Germans, and the Russians listened to everybody. Both East Germany and West Germany were listening in on conversations as well. So everybody knew what everybody else was doing. Every time we were on the phone, there were five different countries listening to every word we were saying. As a result, when unexpected things would start to happen, everybody would know that something was up within 20 minutes.

What happened one day provides a typical example. A West Berlin tour bus was on a short visit to East Berlin. As all of Berlin was occupied by the four powers there was an agreement that West Berlin tour buses could visit East Berlin. The East German government, actually the Russian government because Russia was in charge of East Berlin, permitted these tours to take place.

So one day an elderly American had a heart attack and died on one of these tours to East Berlin. In the consulate, we heard that something had happened on the bus. And so, we tried to find out what had happened and eventually found out. The people on the bus tried to get back to West Berlin with the body on the bus because they knew there would be a lot of difficulties if they had to leave the body in the East. But they didn’t make it, and it became a big deal. The wife of the dead man stayed for a while, but she could not get permission to return with her husband’s body. The Russians came and took the body away from the bus, and the East Germans kept the body. In these cases, it was always very unclear who took what action, but usually it was the Russians who made all the decisions. So, they took the body, and they held the body, and it took us around two weeks before we eventually got that body back. And when we did, it was stripped of everything. There was no jewelry, no clothing on the body. Nothing. That is one example of the Cold War.

“She was waiting and waving. She was about 100 yards away, but that was an eternity. One hundred yards could have been 100 miles.”

And another day, late in the afternoon, we got a call from Tempelhof Airport (and by the time we got the call, everybody knew what was happening—the Russians knew, the British knew, everybody knew what was going on). On this day, two little American kids had been sent on their own to see their grandmother in East Berlin. They were about 10 and 12 years old. And we started talking to their parents in the U.S. (most of these kinds of kids came from parents whose fathers had been in the U.S. military and mothers were from Germany). It took us a while talking to the parents to realize that they had ticketed the kids to West not East Berlin.

Around six o clock, Tempelhof Airport officials called us to say they were closing for the night. The kids had been there for several hours, and their grandmother was supposed to meet them. They were quite upset. They were crying. So the mission duty officer, Felix Block, and I went to Tempelhof and picked the kids up and took them over to Felix’s house. His wife cooked them a hamburger for dinner. They were very upset and afraid but happy to speak English. Meanwhile, we then kept getting phone calls, and learned the grandmother had been located in East Berlin. The Russians had found her (probably at East Berlin’s airport) and had taken her to the East Berlin side of Checkpoint Charlie.

The American military thought that if we could get the kids to the checkpoint, we could probably get them over to the East. Felix and I and the kids went to Checkpoint Charlie around 9:00 pm. We passed through the American checkpoint to the Russian checkpoint. We then just sat there with these kids. We talked with some Russian soldiers, explained to them what had happened. Then we were sent to another room.

We stayed there for an hour or so. The kids were really losing it by this time. And eventually, we went outside with the very distraught little girl and the grandmother was visible on the eastern side of the checkpoint. She was waiting and waving. She was about 100 yards away, but that was an eternity. One hundred yards could have been 100 miles. Eventually the little girls broke down and just started sobbing. And suddenly things started to happen. The Russians then said OK, we can see that she’s not going to hurt anybody. Her grandmother’s there. So Felix and I kept advancing from one barrier to the next barrier. And eventually about midnight we were able to push the kids into East Germany and they were able to join their grandmother. And so that was one example of the rare human side of the Cold War. The kids had their summer visit with Grandma and were able to return to the U.S. at the end of the summer.

———————

William Bodde

Berlin, Germany—Political Officer, U.S. Mission 1973-1977

Read William Bodde’s full oral history HERE.

“You can just imagine what the East German guards must have been thinking when they saw this tank headed towards East Berlin with the cannon pointed at them.”

Root Phelps was the FSO at the mission who was the primary liaison with the military. He had a special military phone in his bedroom because he’d get calls day and night. If something happened at the Wall or if something happened at a checkpoint they would call Root for instructions. Often they were trivial calls: should we fly the flag this way or that, etc.

One night he had already had four calls in the middle of the night. The phone rang and he was really furious, “What do you want now,” he grunted into the phone. The voice on the other end said, “Mr. Phelps, there’s a combat-loaded M1 Abrams tank headed for Checkpoint Charlie.” A GI had found his wife drinking with some other GI in a Gasthaus. He was drunk himself and got really angry. He was a tank driver so he went back to the tank park. He got in his tank, started it up and crashed out through the front gate. He apparently planned to defect to East Berlin with a U.S. tank.

When tanks are not actually in combat, they have their turret turned around and the cannon facing the rear. Well, he had his cannon up and in the firing position. I don’t think you can’t drive a tank alone and fire the cannon, but you could bring it to a halt and fire away. You can just imagine what the East German guards must have been thinking when they saw this tank headed towards East Berlin with the cannon pointed at them.

As the tank headed for Checkpoint Charlie the military police (MP) tried to corral it with MP sedans but they just bounced off the tank without stopping it. When he got to Checkpoint Charlie, he couldn’t get through the anti-tank barriers so he turned around, and he headed back towards the other side of town to Checkpoint Bravo. Bravo was the entrance to the autobahn that goes from Berlin to West Germany through East Germany. When he got to the checkpoint he crashed through the American checkpoint but got hung up on the East German side which was manned by Russian troops. The tank had thrown a track.

So there we had an Abrams tank with all the latest equipment stuck at the Soviet checkpoint. Well it just so happened that the captain of the guard on the American side and the captain of the guard on the Russian side had established a decent working relationship. The Russian calls our man up and says, “I got your tank here, and you’ve got one hour to get it out of here.” They held the soldier for a few days and then sent him back. I talked to the chief army mechanic who was in charge of fixing it. He said usually it takes three or four hours to get a track back on a tank but he proudly said we did it in less than an hour. I’m sure the Russian officer got in trouble for being so cooperative. The incident sure caused a bit of excitement.

“Oh boy, I thought now I am in trouble. There’s going to be an incident.”

. . . There were always tensions about the Wall and you worried about screwing up whenever you went back and forth to East Berlin. We were encouraged to go over there to the museums and opera to demonstrate the Allies’ right to enter East Berlin anytime they wished. We always worried whenever we went over there that we might do something to violate status such as surrendering our passports to an East German guard.

I went through one time with my wife. You had to show the East German guard your passport through the car window, but not give it to him. So I held up my passport, she held up hers, and the East German guard kept shaking his head no. Oh boy, I thought now I am in trouble. There’s going to be an incident. They’re going to take us out of the car, and the U.S. Mission will go crazy. It turned out that in our nervousness I was holding up her passport, and she was holding up mine.

——————————————–

Ambassador H. Kenneth Hill

Berlin, Germany—Consular Officer, Political Officer (1968-1972)

Read Ambassador H. Kenneth Hill’s full oral history HERE.

“And so he was sent to me and I checked with Washington and found out that he was wanted by the FBI for hijacking an airplane from Atlanta to Havana.”

We had a few cases of Americans who got arrested in East Berlin and who at some point, sometimes after a year of incarceration, would be released and sent across the Sandkrugbruecke [a bridge at the Berlin Wall between East and West Berlin]. I’ll mention one case in particular. A person showed up in the visa section down the hall from my office with a Cuban laissez-passer [a substitute passport] asking for a visa to the U.S. But the laissez-passer indicated the person was born in the United States. And so he was sent to me and I checked with Washington and found out that he was wanted by the FBI for hijacking an airplane from Atlanta to Havana. He was considered dangerous, and so I was advised to take measures to protect myself.

In the following days, the FBI and the State Department considered several ways to arrest the man so he could be returned to the U.S. and tried for the hijacking. The FBI was especially keen to have a conviction of a hijacker in the hope that it would discourage the crime which had gotten out of hand. But there were concerns that the various plans might jeopardize convicting him in court.

I was anxious to get the man out of Berlin lest journalists learned of him. So I informed the Department, and the man had told me he wanted to return to the U.S. and “face the music.” He was tired of running, he said. So I suggested that a former Texas sheriff working in the public safety office at the mission and I, unarmed, could escort him on a commercial flight to New York. My suggestion was approved and we were successful in escorting him to New York and turning him over to the FBI, who were waiting for the flight at JFK airport.

Q: Do you know what happened to him?

HILL: Yes, he went on trial in Atlanta, Georgia and was convicted and given a twice-life sentence in prison. I assume he is still serving his sentence.

Q: Good God.

HILL: During the flight the former sheriff talked with the hijacker while I was taking a nap. The hijacker apparently discussed in detail why he had taken over the airplane and diverted it to Cuba, thus freely admitting the crime. And so my friend was called to testify at the man’s trial in 1969 or 1970.

“He was rejected by everybody, a hot commodity that nobody wanted, even to give him asylum.”

Q: Well, how did the man hijack a plane to Cuba and end up in East Germany?

HILL: The Cubans gave him a laissez-passer and wanted to get rid of him. He used the document to travel to Prague, where he went to the embassy and offered to return to the U.S. So under instructions from the Department, the embassy gave him a non-refundable voucher to buy a one-way airline ticket to New York. But on the way to the airport, he jumped out of the car at a stop light and traded his voucher for a ticket to Guinea in Africa. The Guineans wouldn’t let him enter their country even though he was an African American, and they put him on the plane returning to Prague. From there he traveled to East Berlin.

When he showed the East Germans his laissez-passer and asked for assistance, they said, “Oh, you’re an American. You need to go to West Berlin and talk to them.” He was rejected by everybody, a hot commodity that nobody wanted, even to give him asylum. So he ended up in my office.

Years later the man from prison filed papers to sue thirteen American officials for a million dollars each, including an unnamed Foreign Service Officer, who with another man, both armed he claimed, abused him and violated his rights, and forced him to return from West Berlin to the U.S. Of course his claims that we were armed, had abused him, and had forced him to return to the U.S. were entirely false. I was alarmed that I might become involved in a lengthy legal case but the Justice Department had the suit dismissed as frivolous