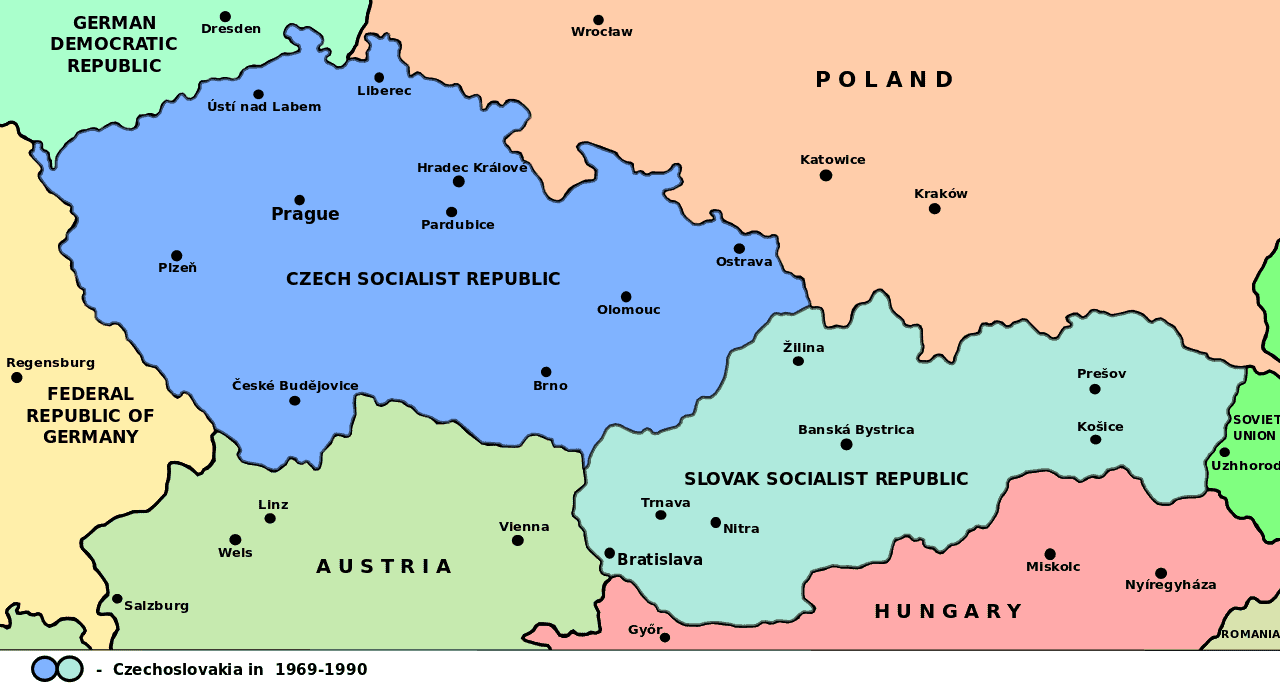

Most divorces do not end well, and those between countries tend to be the messiest of all. The dissolution of the USSR was no exception to this rule as the nation itself, along with many of the individual states within it, fell apart in the early 90s. However, one country, the Federal Republic of Czechoslovakia, proved resilient to the tendency towards violence and conflict when a state splits.

The Velvet Revolution freed Czechoslovakia from communist control in 1989, and the first democratically elected government came to power soon after. However, tensions quickly arose between Czech and Slovak leaders as the later’s politicians demanded more decentralization while Czech politicians advocated for greater control from Prague.

Nevertheless, a split between the two groups was not inevitable. A strong majority of both ethnic Czechs and Slovaks opposed dissolution, and relations between the two groups were generally strong. Furthermore, remaining united also brought economic benefits for both sides, especially for the relatively less developed region of Slovakia. Yet, the two groups were relatively disunited even if there was no active dislike. Neither Czechs nor Slovaks had much media presence in the other region. Bratislava was viewed as a cultural backwater compared to Prague, and there was an undercurrent of economic resentment on both sides. However, none of these issues proved insurmountable in the early years of the newly liberated republic.

In 1992, the two leading elected politicians, Václav Klaus for the Czechs and Vladimír Mečiar for the Slovaks, met to attempt to hammer out a compromise determining the shape of Czechoslovakia’s government moving forward. Klaus was an economist for whom liberalizing the Czechoslovak economy after the stringent rules under communism was paramount. Mečiar, on the other hand, opposed this rapid shift towards a free market. This stance, combined with his strong desire for greater Slovak autonomy, quickly made any agreement between the two near impossible.

In July of that year, both leaders realized they could not find a compromise; they agreed to split the country into two separate nations. No referendum was held although polls showed that the general populace on both sides opposed the divorce; this disinterest in splitting the country hence played a large role in the calm nature of the eventual dissolution. Unlike many other former Soviet states, the two major ethnic groups had no antipathy towards each other. Thus, there was no desire for violence towards each other when a majority of people did not even want the country to dissolve.

The two nations officially split on January 1, 1993, but whether this action was inevitable or merely a result of two proud leaders and the unique circumstances of the times continues to be debated. Nevertheless, the Velvet Divorce provided a rare example of how differences between two groups could be settled peacefully, and it is the only nonviolent dissolution of a state in the post World War II period. One can only hope that this lesson will not be forgotten as regional groups continue to demand independence and greater autonomy today. Former Foreign Service Officers Theodore Russell and John Evans discuss their times serving in both Czechoslovakia and the two states that emerged from it, along with their thoughts on the split and its consequences.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Drafted by Ty Ashton Ehuan

John Evans

Prague, Czechoslovakia—Consular Officer (1975-1978)

Prague, Czechoslovakia—Deputy Chief of Mission (1991–1994)

John Evans was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy on October 19, 2009.

Read John Evans’s full oral history HERE.

Theodore Russell

Prague, Czechoslovakia—Deputy Chief of Mission (1988–1991)

Bratislava, Slovakia—Ambassador (1993–1996)

Theodore Russell was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy on February 22, 2000.

Read Theodore Russells’s full oral history HERE.

Excerpts:

“. . . it was not clear to us that they were going to split.”

Czech-Slovak Relations Under Communism:

Q: Did you see a major split between Slovakia and the, later the Czech side of things?

EVANS: We were aware, one cannot fail to be aware of the differences between the Czech lands, which are Bohemia and Moravia, and the Slovak Republic, which was, after 1968, made a full republic in addition to the Czechoslovak Republic. Bohemia and Moravia were not a separate republic, but Slovakia was and it had its own Communist Party whereas the rest of the party was the Czechoslovak Communist Party. And you do see the differences, cultural and language differences, of course, when you go to Slovakia. Originally the Czech lands were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire ruled from Vienna whereas Slovakia was ruled from Budapest and that has a lot to do with the differences, and there also is a sizeable Hungarian minority in the south of Slovakia. So yes, in my travels around I did run into this but I have to say that the level of expression of nationalistic feelings was quite low. Czechs love the Slovaks; Slovaks bridled to some extent under what they saw as something of a patronizing attitude by the Czechs but there were a lot of Slovaks who had ended up in Prague as “federal” Slovaks. And in fact, there was a saying, and I can’t quote it now, it works better in the local language, but it basically was a saying that “Czech lands are now ruled by Slovaks” because there were so many, starting with Gustav Husák and his other Slovak colleagues.

****

Q: The issue became very important to you later on, but were you seeing any fissures between the Czechs and the Slovaks at that time?

RUSSELL: Not a lot. We were seeing some reports even at that early date that some of the Communist officials were favoring more Slovak autonomy on the grounds that the Czech approach was going to be tougher on them than what they might experience in a more autonomous Slovakia. We had a few scattered reports coming in saying these guys thought they would be better off if they could get further away from the reach of Prague. However, these were really straws in the wind. What we did see is that the Slovaks not surprisingly wanted to get greater autonomy now that they were free of the Communist control. They wanted to go back to what they were trying to get in 1968. Part of the deal in ’68 was democracy. Part of it was more autonomy for Slovakia that Dubcek was particularly pushing. So they wanted to follow up on that and get much greater autonomy, but not necessarily independence. We saw that as a possible area for friction, but it was not clear to us that they were going to split.

“They said, “There isn’t a Slovakia.” I replied “Yes, but there will be.””

Reasons for Divorce:

RUSSELL: We knew for certain that Slovakia was going to demand more autonomy as soon as they got the chance. It was predictable and not a bad thing. I guess in the summer of 1992 I started talking to Personnel and said, “I want to be considered for Ambassador to Slovakia.” They said, “There isn’t a Slovakia.” I replied “Yes, but there will be.” It was clear to me already by then that things were moving in a direction where there might very well be a Slovakia, because I knew from having dealt with him in Prague that Vaclav Klaus, the Czechoslovak Prime Minister from July 1992, was not going to do anything that would compromise the Czech part of the economy and his planned reforms. He would make any deal with Meciar, who was the Slovak Prime Minister, short of one that would compromise the economy. What Meciar essentially wanted was a loose federation, not a split. He was not demanding an independent Slovakia. He wanted everything short of that because among other things there were substantial economic benefits to remaining linked to the more prosperous Bohemia and Moravia. Meciar simply demanded more than Klaus was willing to give. I think Meciar was surprised when Klaus refused and felt he had been pushed into a definitive split rather than having chosen it himself. But Meciar then accepted the split and took great pride in characterizing himself as the father of Slovak independence. I remember Havel was extremely upset by this notion of splitting and was very much against it. But Klaus and Meciar declined to hold a national referendum on it. Polls showed that a large majority of Czechs and Slovaks would have voted against splitting at that point.

****

“…the politicians wanted to keep control.”

EVANS: President Havel had a little bit of a blind eye for what was happening in Slovakia; he was very much a creature of Prague, a Czech through and through. He made some efforts to woo the Slovaks but it didn’t work. They saw him as a Czech and they didn’t like the kind of . . . . I mean, the Czechs and the Slovaks speak a slightly different language and when they heard Havel it just sounded so Czech to them and they didn’t like it. On the other hand, Václav Klaus, who today is the president of the Czech Republic, his wife was a Slovak, is a Slovak, and an economist, and she had a connection to the Slovak premiere, Mečiar, who was a populist and we didn’t very much care for Mr. Mečiar, he was of the old school, but the Klauses to some extent . . . . Klaus was then the prime minister . . . coached Mečiar and helped Mečiar and both sides wanted the split to happen. The Slovaks wanted their own capital, Bratislava, to be on the map, to be a place that people, foreigners, visited in its own right, not as a weak sister to Prague, as an afterthought where people spent half a day after spending two days in Prague. And the Czechs, for that matter, wanted to spin off Slovakia, which was less developed economically. The Czechs felt that they were more industrious and could make it better on their own.

. . . strictly speaking the velvet divorce was probably unconstitutional. But the politicians wanted it; the political classes of both parts wanted this split. There were some who got caught. For example, after the Prague Spring in 1968 a number of Slovaks had been brought by Gustav Husak, the Slovak party chief of communist Czechoslovakia, he brought a number of Slovaks to Prague and they were called “federal Slovaks.” And so they had their homes in Prague, their families in Prague; many of them had married Czechs and they were really Czechoslovak and for them it was very difficult because the country they had served, Czechoslovakia, no longer existed. At the same time there were new people coming up in Slovakia who didn’t have this affinity for the Czechoslovak experiment and really felt themselves Slovak. There are also religious differences involved and you can trace the differences back into history. Slovakia was always under the Hungarian crown in the dual monarchy, whereas Bohemia and Moravia were under the Austrian crown. So there were differences that emanated also from that.

****

Q: Had there been talk of a plebiscite?

EVANS: Oh, there were many things that were talked about, yes. But that option was rejected; the politicians wanted to keep control.

Q: I mean this is a political fait accompli or something by the political class.

EVANS: That’s right, that’s right.

“And I had to, as patiently and politely as I could, explain that Czechoslovakia was not Yugoslavia, that in our view both sides were moving in the direction of a peaceful divorce, a velvet divorce . . . .”

U.S. Response:

EVANS: . . . Ambassador Black and the State Department did not want to see Czechoslovakia divide. That would be seen as a failure of American diplomacy. We had been involved in the birth of Czechoslovakia under Woodrow Wilson. Tomáš Masaryk was the founder of the first Czechoslovak Republic and so there was a deep bias against any splitting up of Czechoslovakia.

One of my political officers, Eric Terzuolo, and I saw very clearly that we somehow had to get the word back to Washington that the split was coming. Now, this would have been in 1992 . . . we got the word back to Washington that they should expect this to happen, and why it was not the Balkans and why we should not overreact to it, that this was something that could be accommodated, that it was not going to be a violent event, we should brace ourselves for it and not get in the way of it.

. . . Once the cable had gone, of course, it had gone and it was out there, and before too long I got a call. I was Chargé still and I got a call from Deputy Secretary of State Eagleburger, and he said “John, don’t you think I ought to come out there and knock some heads, I mean between these Czechs and Slovaks?” And I had to, as patiently and politely as I could, explain that Czechoslovakia was not Yugoslavia, that in our view both sides were moving in the direction of a peaceful divorce, a velvet divorce; in fact they were having frequent meetings between the two sides, usually in Moravia, which is kind of in the middle, and they were talking about a cooperative divorce. And of course in the end that is what happened. It gained steam and momentum.

“. . . I think that once they split, gradually you had a growing majority accepting the notion of Slovak independence and supporting it.”

Czech and Slovak Reactions:

RUSSELL: . . . I was convinced well before the split that this was going to happen. The way the U.S. looked on it was that it was not good for the Slovak economy in particular. The feeling was that this was not a good thing for either side because they were only a country of fifteen million splitting into ten and five. Slovakia had a large Hungarian minority population and a weaker economy and the situation in Ukraine made it a risky neighborhood. On the other hand, it was not our call. Our position was “Do it democratically and peacefully and good luck.” After the split, we immediately recognized them both and asked “What can we do to help?”

. . . I think that once they split, gradually you had a growing majority accepting the notion of Slovak independence and supporting it. Many Slovaks felt that the Czechs had always treated them like little brother. There is certainly a big majority which wouldn’t want to go back but would rather be independent.

. . . The Slovak economy took a bigger hit after the collapse of the Soviet Union, because they depended a lot on their heavy military industry. They had a lot of tank and APC factories in Slovakia and produced more than half of Communist Czechoslovakia’s huge output of military equipment, most of it sold to the Middle East and South Asia. Czechoslovakia was one of the top ten arms producers in the world. These heavy defense industries were mainly in eastern Slovakia where the Soviets wanted them so they were further behind the lines. Some had been moved there before World War II. They were doing very well under Communism.

****

“. . .the two parts of the country clearly were on different tracks and there was no real violence.”

EVANS: . . . at first people were shocked by the split. A lot of Slovaks were married to Czechs. So there was initial shock, and then there was a funny reaction. It was almost as if the Czechs reacted by saying, “Well, okay, they wanted that; to heck with it, because they caused this split and they were the ones who benefited most economically from being with us. If that is what they really want, let them have it.” There was some of that kind of bitterness in the initial Czech reaction. The Slovak reaction became “That’s too bad. We don’t dislike the Czechs, but we are glad to have our independence; now let’s see what we can do.” There were mixed reactions to it. However, the Visegrad countries, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary, are now working very closely together to help each other get into the EU and to help Slovakia get into NATO because Slovakia leaves a big geographic hole in the area. This has brought the Czechs and Slovaks back closer together. They have settled virtually all of their outstanding problems stemming from the split. There was the problem of how to divide the national wealth. There was the question of Slovak gold being held by the Czechs and how much they should pay to get it back and small border adjustments that under Meciar couldn’t get solved because he always took such a tough approach to things.

. . . after the split, I had the impression that some Czechs were saying “well if that’s the way the Slovaks want it, let them go their own way.” Some Slovaks on the other hand were probably saying now “the Czechs aren’t going to boss us around or act like big brother anymore.” But it was a totally peaceful split. It wasn’t unfriendly. The Slovaks and the Czechs don’t dislike each other. They are pretty close culturally and linguistically. Their languages are mutually intelligible. They were together from the end of World War I, with the sad hiatus of the Clero-Fascist Slovak State during World War II, until the end of 1992. They are pulling closer together now and I think there is a feeling of shared interests in Central Europe now that is very positive, including particularly between the Czechs and Slovaks.

. . . the two parts of the country clearly were on different tracks and there was no real violence. There might have been a fight or two in a pub and some words issued in different directions. But there was no major clash or violence.