Long regarded as a monolithic entity where any dissension was ruthlessly suppressed by the KGB, Western audiences often ignored the intellectual culture of the Soviet Union. However, this viewpoint dismisses the underground scene of Soviet dissidents who played a critical role in speaking out against and documenting the abuses of the regime.

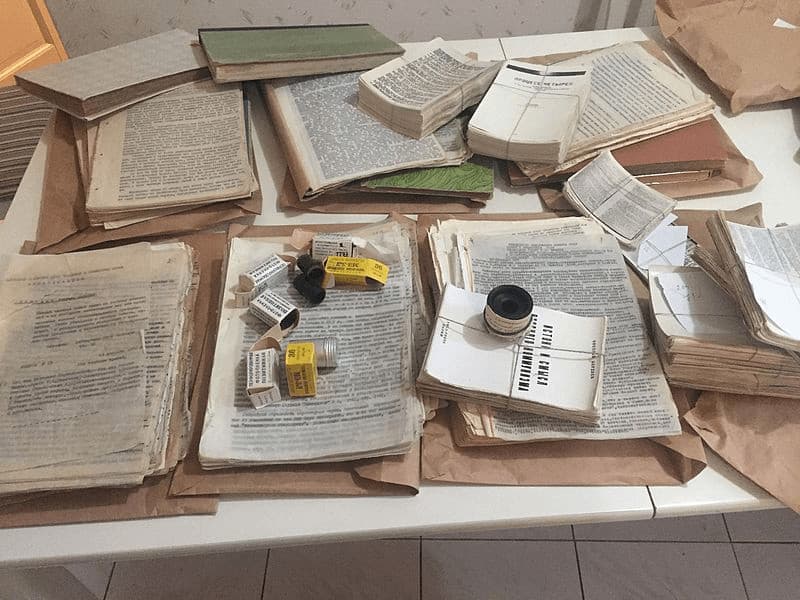

Whether through human rights movements, subversive art and literature, or even religious protests, Soviet citizens fought back against the government in a variety of ways. One particularly notable method was that of “samizdat” where Soviet individuals reproduced contraband material by hand to escape government censorship and inform the everyday person. Nevertheless, these methods were fraught with risk, and only a small coterie of brave citizens worked tirelessly to continue the struggle.

A hotbed for this defiance was located under the feet of the Politburo, taking place in Moscow itself. Though disunified and disorganized to prevent their destruction, a multitude of Soviet intellectuals gathered in Moscow to protest for their chosen causes. A strange tolerance existed within this space as the government capriciously charged dissidents seemingly at random. Nevertheless, these writers, painters, and thinkers ran the constant risk of being sent off to Siberia or even killed outright by an authoritarian government that would do whatever was necessary to ensure its survival.

William Luers served in Moscow at the start of his long career in the Foreign Service and later consulted on Soviet affairs while working in Washington. He was one of the first U.S. officials to discover this thriving underground scene within the Eastern Bloc and repeatedly worked with it, even at the risk of his own safety. His firsthand accounts show the dangers these dissidents faced as many of the people he met with were jailed or killed; but the bravery they demonstrated in the face of this threat had a profound impact on the eventual fall of the USSR.

William Luers’ interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on May 12, 2011.

Read William Luers’ full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Ty Ashton Ehuan

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“Andrei also told me to never try to be secretive about my contacts with him or with any Soviet citizen. He said, ‘always ring the bell.’”

Introduction to the Moscow Underground: I had come to know a Russian dissident named Andrei Amalrik in the first week after I arrived for my Moscow tour. A FSO friend Jack Matlock (later American Ambassador in Moscow) introduced us, before Jack left post on reassignment. Andrei was a playwright who knew the vast Moscow underground of writers, painters, and intellectuals. During my two years in Moscow, he introduced me to many painters and writers. No one else in the Embassy knew or spent time learning about this world – even though Matlock had begun to penetrate it before he left. I got to know a whole group of painters and became a collector of Soviet underground paintings.

Through Andrei, I got to know painters and a number of the more controversial dissidents who were tracked, as Andrei was regularly by the KGB. Andrei knew the KGB and they obviously knew him, even though I do not believe he ever worked as an agent, as you will see when I tell you this story. Andrei explained that the KGB division that followed him and his dissident colleagues was an entirely different division from the one that tracked diplomats or other foreigners. Andrei believed that in the large KGB organizations those two parts probably did not talk to each other.

Andrei also told me to never try to be secretive about my contacts with him or with any Soviet citizen. He said, “always ring the bell.” By that he meant call from the embassy phone and speak clearly about what I want and where we should meet. He said that staffs in some embassies have the habit of going to a nearby public phone to call, which of course is closely monitored and the KGB just concludes the diplomat is trying to conceal something which, as Andrei knew, was not easy to accomplish in that police state.

I did come to know this underground world better than any of the other diplomats, including American, in Moscow at the time. My extensive travel with visiting American writers and painters also gave me added insights into Moscow’s vibrant intellectual life that had not yet been fully appreciated outside of the USSR.

“The Western media was not aware of this substantial underground world of painters, playwrights, musicians and political dissidents.”

Publicizing Opposition: I spent a great deal of time during my tour trying to explain to select American correspondents about this Moscow underworld, and few of them were interested. One close friend, Bud Korengold, the intelligent Newsweek bureau chief, was interested. Bud and I began to think about ways to get this story out without compromising my diplomatic status and without getting him kicked out of the Soviet Union. In the early 1960’s the perception of the Soviet Union was that it was a monolithic passive communist state in which most dissidents were in Siberia or under tight control. The Western media was not aware of this substantial underground world of painters, playwrights, musicians and political dissidents. For the many reasons I have explained, I had gotten to know some of the key intellectual and dissident players in Leningrad and in Moscow. There were shades of different “opposition” intellectuals from some of the “bold poets” (like Yevtushenko and Voznesensky) who were officially accepted but always pushing the edges of approved literature. At the other end were dissidents like Ginsberg and eventually Amalrik who came openly to oppose the system. I subsequently wrote a long article about Moscow’s underground world of culture in Problems of Communism, a USIA publication.

The opportunity came to get this story public when a young Soviet painter, named Zverev (meaning wild one), had an exhibition of his paintings in Paris. I knew him quite well and he had done a portrait of me and my wife and others that I brought to him. He was in his 20’s, looked “wild” and drank a great deal of vodka. He drew brilliantly and did semi abstract paintings with a flourish that was unique. A group of his friends, probably from the French Embassy, were able to sneak out some of his paintings to an exhibition in Paris. News of the exhibition became known internationally when Picasso visited it, praised the artist, and bought a couple of paintings. I told Korengold, “This is an opportunity. We will get you a picture of Zverev’s dramatic self-portraits that you can put on the cover of Newsweek magazine. You can use that and the exhibition as a vehicle for talking about the underground art world in Moscow.” I told Korengold that Andrei could arrange for Zverev to meet us at Andrei’s apartment for a brief meeting on Thursday at noon (all times and locations were always exact in Moscow and you were never to be late). When Korengold agreed with this plan, I called Andrei from my office in the embassy to “ring the bell” for the KGB. Andrei always said to let them know what you are doing. If they want to stop it from happening they will stop it.

Korengold and I arrived right on time at Andrei’s apartment. In the Soviet Union if you are not there on time you can assume there must be a problem. We rang the door of his communal apartment that he shared with his father. Since the communal apartments meant two small rooms in a larger apartment, someone else in the apartment actually came to the door. We went to Andrei’s door nearby and entered. Andrei was there but Zverev was not. I said to myself, this is not good news.

I said, “Oops, there’s a problem. Where’s Anatoly (Zverev)?”

Andrei said, “He’s apparently a little delayed.”

I thought to myself that I never felt good about a delay.

Then within minutes there was a knock on the door and two KGB agents and a local policeman entered Andrei’s apartment. The top guy knew Andrei, you could tell. He called him Andrushka (the often-affectionate diminutive for Andrei). He asked “What are you doing now?” They believed that Andrei was trading in hard currency (dollars) and violating the law. I had no impression that he was making any money on the paintings he arranged for me to buy from other painters. In any case, the amount of cash was very small and we would always pay in the Soviet equivalent of hard currency. I never gave him dollars. Rather than linger to talk to the KGB, I took Bud Korengold, who did not have diplomatic immunity, with me out of the apartment within minutes after the KGB had arrived. We took off and we went back to the embassy where I immediately reported to the embassy security officer and to my boss, Malcolm Toon, who was then political counselor (later ambassador).

“I came to understand that Andrei had decided it would be a banner of courage as a Russian dissident in the centuries old tradition of ‘sitting’ in Siberia.”

Soviet Response: The next morning after I had gone to the embassy from my apartment outside of the embassy, my wife called to ask me to come home at once. I returned back to the apartment many blocks away to Andrei, who had come to talk about what happened. Andrei said, “They’re going to send me to Siberia because I’m a parasite.” The Soviet term in Russian for someone who does not have a full time job is tunyadetz or parasite. If you are not working you are a parasite, sucking off of the society. After much talk I asked Andrei, “Well, why don’t you just get a job?” Mind you all of this was in the living room of my apartment.

Andrei replied, “I’m not going to accept their charge that I am a parasite. I’m a playwright, I do what I do, and I’m not going to conform to their view of what work is in our society.” I couldn’t talk him out of accepting his being sent to the “camps” in Siberia. Every room in my apartment was bugged. (The embassy security did not even try to find out how many ways, since technology was changing all the time and we had Soviet citizens living all around us in the building. We had just come to live with that reality in a conversation.) We had this candid conversation during which I came to understand that Andrei had decided it would be a banner of courage as a Russian dissident in the centuries old tradition of “sitting” in Siberia. He had decided that he wanted to define himself clearly in opposition to the Soviet regime. He subsequently was tried and was sent to Siberia.

When I returned to the embassy after my conversation with Andrei, my boss, Mac Toon, said angrily, “Luers, you are going to get yourself kicked out of here by the KGB. You have been traveling around Moscow and the rest of this country for over two years, meeting with all these Soviets, most of whom are KGB. I have told you to stop seeing these people since they are all the same and will be turning you in.”

Mac Toon was extremely intelligent, a strong leader, and he hated the Soviets — not just the government and party officials. He really disliked the entire society, and the Soviets reciprocated since they knew well his point of view. Mac did not like to be in the presence of Soviets except when required by ceremony or process. He spoke Russian well, but was on edge any time a Soviet was around. He was convinced that all these people I was seeing were KGB agents. I was certain that some of them were, some of them were not, but most of them were passing on information on me. But I had gotten into a world that I knew had a large element of authenticity such as Andrei: people who struggled to be apart from the system, deal with it yet detest.

My job was to report regularly back to the Department of State and the broader intelligence community on my experiences. People who followed the Soviet system and society in the American intelligence community, mainly the analytical side, took great interest in my reporting since I was getting aspects of Soviet society we had not reached before. I identified individuals and issues that demonstrated that even at the height of the Cold War, after the shoot down of the U-2 under Khrushchev, there had emerged intellectual life that showed that the society was coming alive.

….

“He outlined the qualities of the system that were decadent, ineffective and self-destructive that raised for him almost a certainty that it would not survive.”

Impact of the Moscow Underground: When I went to Moscow I really was quite a traditional Cold Warrior and I had a profound dislike for the system and the communist ideology. I wasn’t for bombing them, but I was negative on the structure of society. But because I had gotten to know more of the Russian language, become close to some native Russian teachers in Oberammergau, and traveled so broadly in the Soviet Union, I got to know the political diversity and opposition within the country to the Soviet regime and came to appreciate the real distinction between the Soviet population and the Communist Party. I became ever clearer on the impact that these Soviet popular attitudes were having on the productivity of the country and even its stability.

In 1966 I published in a USIA magazine, Problems of Communism, edited by my good friend Abe Brumberg, under a pseudonym Timothy McClure. I summed up my analysis of the wide variety of political/cultural trends that were forming in Moscow during my time there. The article received wide readership because it was unique and it was subsequently published in several books of essays on contemporary USSR. Looking at the human side of Soviet diversity allowed me the opportunity to help paint the picture of a nation that was not a monolith but a vast diverse collection of ideas, frustrations and dreams that eventually began to become obvious to all following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

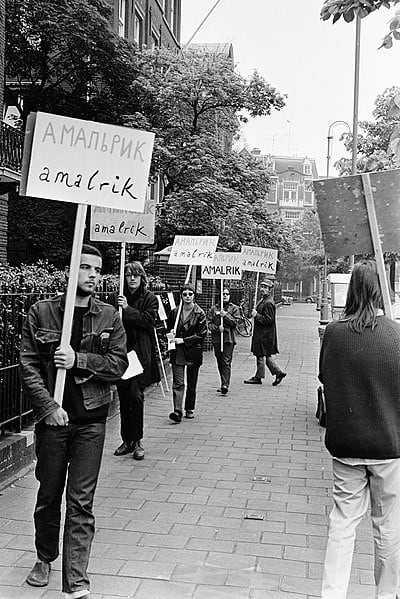

. . . . By the way, Andrei Amalrik was sent back to Siberia after Involuntary Trip to Siberia was published in the West. During his “second tour” there he wrote a book that was later published in the West called Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984, drawing directly from the title of George Orwell’s classic book on the totalitarian experience. Andrei addressed in this book his serious doubts about the durability of the Soviet. He outlined the qualities of the system that were decadent, ineffective, and self-destructive that raised for him almost a certainty that it would not survive. As you recall, the Soviet Union began to collapse in 1989, so Andrei was only about 5 years off in his prediction.

. . . . My view was that the Soviet regime was a terrible regime but the country was populated by many brilliant and fascinating people. And I do believe that my association with Amalrik and his book, Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984, and that whole philosophy, gave me real skepticism about how long they can endure.

….

“It became ever clearer to me over the years that the mentality and mode of operations of the KGB and CIA/FBI were very similar.”

State Department Interest: When I returned back to State Department I had the impression that there were a certain number of people who followed Soviet issues who had come to learn from my reporting. So I told the State Department Security office that I would be willing to brief them on what I had learned about the Soviet system and some individuals during my tour. We had several long sessions about my contacts and thoughts about the operations of the KGB and other intelligence operations. But the questioners kept asking me about this one Sunday evening in Leningrad, which was about six months before leaving Moscow. I remained late on that evening since I had been there to arrange a special event for the ambassador. I stayed longer than originally planned, so I took the overnight train back to Moscow. I had been working on the event with a Russian woman called Lydia Goriva, who had been a valuable contact at the Hermitage Museum over the years. She was a curator at the Hermitage Museum. She got me into the museum easily and introduced me to the director of the museum, whom I got to know. She also had introduced me to several artists in Leningrad. She had become my Andrei Amalrik-like contact in Leningrad.

In their interrogations of me, the Security people finally said that they doubted my story about what I was doing before returning late at night and not keeping with my original plans. I suddenly realized what they were after, “I know. You think I was sleeping with Lydia Goriva.” They said yes. And I replied in shock but with a little amusement, “Have you ever seen Lydia?” Lydia was one of the most physically unattractive human beings I had known. She was slightly deformed and she was certainly not sexually appealing. Indeed, I was comfortable that the Soviets would never be so stupid as to deploy Lydia to entrap me. So it became clear that my entire effort to illuminate the Security people about what I learned was for the purpose of getting me to admit to a sexual entrapment. There was nothing and they found nothing. That experience revealed to me the low-level of interest in understanding the Soviet system and what diplomats in Moscow were dealing with. They had no further interest in my reporting. It became ever clearer to me over the years that the mentality and mode of operations of the KGB and CIA/FBI were very similar.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA with Honors in Chemistry and Math, Hamilton University 1947–1951

MA in International Relations, Columbia University 1956-1957

Joined the Foreign Service 1957

Moscow, USSR—Assistant General Service Officer 1963–1965

Washington, D.C.—Deputy Assistant Secretary for Europe 1977–1978

Caracas, Venezuela—Ambassador to Venezuela 1978–1982

Prague, Czechoslovakia—Ambassador to Czechoslovakia 1983–1986