As we renew conversations in the United States about what liberty and justice for all truly looks like, we must reflect on our past. At the State Department, these conversations have long been important to our diplomats; they have prompted many to speak up, to create changes that make the agency a more inclusive and diverse space, and to be advocates for equality abroad by challenging structures which impede justice.

There is still work to do. At a time of uncertainty about the future, we turn to the past to draw on the experiences of those who came before us.

The State Department has a history of a lack of diversity. Women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community have been under-represented within the Foreign Service. For example, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2019 women made up approximately 50 percent of the overall U.S. population. Yet, according to statistics published by the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) in 2019, only 41.2 percent of Foreign Service generalists were women. Similarly, African Americans (who make up about 13.4 percent of the general population) represented only 5.3 percent of Foreign Service generalists. The statistics for the Senior Foreign Service point to an even greater disparity: just 3 percent of senior-level diplomats are African American and only 5 percent are Latino (who make up approximately 18.3 percent of the overall population), resulting in a diplomatic corps that does not entirely represent the diversity of the American people. Despite these systemic gaps in hiring, records show countless individuals within the State Department taking a stand to report honestly on their experiences and promote positive change. For example, in his oral history, Mr. W. Garth Thorburn shares the challenges he experienced as the first Black professional to serve in the Foreign Agricultural Service; however, he also describes the improvements that he saw in the agency throughout his time there. Similarly, Mr. Leonard Robinson’s oral history recounts the fact that in the early days of the Peace Corps, many Americans perceived it as a “whites only organization.” Through his work as the Director of Minority Recruiting for the Peace Corps, it slowly but surely grew to look more like the United States.

In addition to making positive contributions to hiring practices at home, America’s diplomats have made great strides in “personal diplomacy” overseas, particularly when responding to issues of inequality and injustice. We revisit the experiences of James W. Wine, Peter Eicher, and Aaron Williams to explore how each of them embarked on projects to improve human rights conditions abroad. In the Ivory Coast, James Wine held honest conversations with President Félix Houphouët-Boigny about race, equality, and police brutality. In South Africa, Peter Eicher fought for the voices of prominent black activists to be amplified in diplomatic discussions, while Aaron Williams took on numerous projects to improve access to education on the ground.

So what do diplomats do when they wish to make positive changes to domestic or international policies? How do they proceed when they identify human rights issues that must be addressed urgently? In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” we reflect on how diplomats have fought for justice and equality, both at home and abroad.

James W. Wine’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on April 4, 1989.

Leonard Robinson’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on April 29, 2003.

W. Garth Thorburn’s interview was conducted by Allan Mustard on January 16, 2006.

Peter Eicher’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on May 30, 2007.

Aaron Williams’ interview was conducted by Carol Peasley on February 6, 2017.

For more Moments on notable personal diplomacy efforts, click HERE.

Drafted by Abby McCarter and Natalie Schaller

Excerpts:

The following oral history excerpts detail the historic lack of diversity in U.S. government initiatives abroad as well as the personal experiences of public servants who have witnessed and contributed to positive change in the hiring practices of different agencies.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

***

W. Garth Thorburn

Washington, D.C.—Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS)

Read W. Garth Thorburn’s full oral history HERE.

“To see the transition, where we have people of all ethnic groups in responsible positions in the agency, I think is a 180-degree turn.”

The First Black Professional at FAS: I was the first colored professional – back then, we were colored, then we became black, and now we’re African Americans – that FAS hired. And, as I had mentioned, Dr. Wilhelm Anderson decided that he would hire me because I appeared to be qualified, as everybody else. No other person, no other branch chief of division director, wanted to hire a colored person. So I was very, very pleased when I discovered later on that he had hired me. Two years later, Cline Warren, who was a graduate of Purdue, was hired. There was a period of 10 years before any other minority professionals were hired.

The only Blacks that worked at FAS when I was there were in the code room, or the basement, mailroom. To see that we have incorporated into the agency women, Hispanics, Arabs, Native Americans, normal, run-of-the-mill Americans that we expect to see in a U.S. government agency. The USDA at that time, except for the county agents, and there were Black county agents, was said to be one of the most racist agencies in the U.S. government – said to be. I don’t know. I went in there and I didn’t have any problems, but this was what was said. To see the transition, where we have people of all ethnic groups in responsible positions in the agency, I think is a 180-degree turn.

Racism on the Job: When I was hired, there were a few uncomfortable moments. As a matter of fact, OFAR had transitioned into FAS, and there was a filing system, and Ruth Donovan was responsible for setting up the new filing system in FAS. She didn’t have enough help, so she asked the division directors and branch chiefs if they could provide someone, a secretary or administrative assistant, to spend some time, maybe over a period of a couple weeks, two hours a day, in order to help to structure and restructure the filing system, set it up properly.

Well, apparently, none of the secretaries or administrative assistants liked Ruth Donovan and wanted to work with Ruth Donovan. So, each section had to send somebody. So, being the most junior person there, someone suggested that Garth go over there, so Garth went over there. About an hour later, somebody from the administrator’s office came down and said, “We didn’t hire you to do filing.” I said, “Well, I was sent here. Speak to who was responsible for sending me here,” so things like that happened.

***

Leonard Robinson

Washington, DC—Peace Corps

Read Leonard Robinson’s full oral history HERE.

“I thought it was important for the Peace Corps to look like America.”

Focusing on Diversity: Joe Blatchford, when he visited south India, said to me, “Lenny, I would like for you to come back to the States when your tour is over here and head up our minority recruitment division at headquarters. We don’t have enough Peace Corps volunteers who represent the mosaic of America. We need to be more diversified. I think that you can come back and lead the effort to have the Peace Corps revitalized, re-energized by recruiting more African-Americans, Hispanics and native Americans etc.” So that is what I did. . . I had some definite ideas about how to go about diversifying. I really thought it was important for the Peace Corps to look like America. I became the director of minority recruiting for the Peace Corps. I had lots of ideas and a tremendous amount of energy. I felt a tremendous amount of pressure.

“There is no question that the Peace Corps was bereft of people of color.”

Making Lasting Change: During the time that I was a Peace Corps director, I had maybe three working on my projects; maybe in the entire country there were no more than four or five. So in India we had very few African Americans or people of color serving in the Peace Corps. There is no question that the Peace Corps was bereft of people of color.

Just from the advertising, one could have easily reached the conclusion that the Peace Corps was for whites only. I took a look at that in 1970. One of the first things I did was to look at all of the Peace Corps advertising, the brochures, the commercials we had on television. There was one subject of color among all of that media stuff we had, so the perception was, the image was the Peace Corps was lily white. We changed all of that. We developed ads and commercials and brochures that reflected more of the diversity, more of the mosaic of America in the Peace Corps.

That didn’t necessarily help to bring volunteers in. We had a few, but not nearly as many as I would have hoped for. The Peace Corps today is still struggling today with this diversity issue. Obviously more people of color have joined in the past ten or fifteen years. One of the things we did was to clearly try to tie service in the Peace Corps with furthering the volunteer’s education. I initiated a master’s degree program with Texas Southern University in Texas and with Atlanta University in Atlanta. We created a master’s degree program in international affairs in order to allow the Peace Corps volunteers to get not only a master’s degree, but also two years of Peace Corps service. That worked very well in terms of increasing the numbers for Peace Corps volunteers.

***

The previous excerpts detailed the experiences of diplomats working to improve diversity at home in America. Many diplomats have also worked diligently abroad to further conversations and projects that directly address human rights issues, particularly in the Ivory Coast and South Africa. The following excerpts showcase the notable efforts of diplomats James W. Wine, Peter Eicher, and Aaron Williams in this regard.

***

James W. Wine

Yamoussoukro, Ivory Coast—Ambassador

Read James W. Wine’s full oral history HERE.

“He would say something like, ‘I’ve seen examples of man’s inhumanity to man. It happens in this country.’”

Conversations with President Félix Houphouët-Boigny:

WINE: I think he [President Houphouët-Boigny] was a man that had a world vision. He was a man of deep compassion and I think he knew the limitations of his rule, of his government. He kept extraordinarily well informed about world matters and political matters in the United States and Europe.

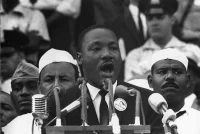

Q: This was the height of the racial problems in the United States, the Freedom Riders, Martin Luther King, etc. As a very sophisticated world leader, how did he view the agony the United States was going through as well as the blatant segregation and animalism?

WINE: I had a long talk with him after the Martin Luther King’s “March on Washington.” He, of course, had seen the television clips of Bull Connor’s episode.

Q: We’re talking about the Alabama police repression of black protesters.

WINE: That’s right, using the water hoses and the dogs, etc. These were not just quick meetings of five-minute visitations. I knew what his signals were when it was time to go, but we talked at great length, most times at his insistence. He would say something like, “I’ve seen examples of man’s inhumanity to man. It happens in this country.”

Police Brutality Across Countries:

WINE: I have been in ceremonies way up-country where his police, when the crowd would come out to view the ceremony and they wouldn’t move back, would take big sticks and whack them.

[President Houphouët-Boigny said,] “I acknowledge these kinds of things. I have an appreciation for the history and the lack of evolving the black persona. It will probably be a philosophical attitude and will probably be a long struggle.”

He was very much impressed with the Martin Luther King leadership. His feeling was that there was a wealth of understanding, good will, and compassion in this country, and that given time, that problem would be not necessarily solved but alleviated in many ways. He was not hostile toward us or openly critical toward the United States, never in my presence. I think he’d seen it all, really, himself. That pretty well explains his views.

***

Peter Eicher

Pretoria/Cape Town—Political Officer

Read Peter Eicher’s full oral history HERE.

“South Africa at the time was very much at the height of the apartheid system.”

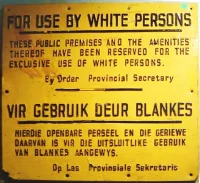

Arriving during Apartheid: The Soweto riots broke out in the summer of 1976, just two or three weeks before I was due to arrive in South Africa, which of course was a huge event. . . South Africa at the time was very much at the height of the apartheid system, officially called “separate development,” but in fact a system of very strict segregation, that was vigorously enforced through a very harsh police apparatus. Apartheid affected all facets of life – where people could live, or work, or eat, or go to school or to the movies, even what public benches they could sit on. It was accompanied by a strict “pass system,” under which blacks were officially not citizens of South Africa. Instead, they were assigned on a tribal basis as citizens of small, unviable “homelands” or “Bantustans,” even if they had lived all their lives in a South African city. They weren’t permitted in “white” areas – most of the country – without a pass; if they didn’t have a pass they could be arrested and deported to a “homeland” that they might never even have visited before.

The Afrikaner-dominated Nationalist Party was firmly in control of the government. It saw the policy of apartheid as a solution to the racial problem in South Africa in the sense that it would strictly divide the races, reinforce tribal divisions within the black community, and create a number of these supposedly independent countries, which would provide a façade to show the world that the blacks really had equal rights.

The Soweto riots of 1976 were the start of a very long period of serious urban unrest in South Africa in opposition to the system. It was the first sustained, widespread, black action in opposition to the regime.

“It was to a large extent up to the younger officers to get out into the townships and meet people and find out what was going on.”

Taking the Lead:

Q: Often when you come to a situation where things are changing, it’s the junior officers at the embassy who sort of get out and around more than the more senior officers, who are sort of trapped in their positions of the establishment. And so they often depend on the junior officers to really get out and take soundings and all that. Did you find that situation in South Africa?

EICHER: We did, yes. . . There, I think it certainly was the more junior officers who were getting out much more and knew people better. The more junior officers tended to be more radical, if you will, more anti-apartheid, or at least more apt to be actively or outspokenly anti-apartheid, than the more senior officers did. It was to a large extent up to the younger officers to get out into the townships and meet people and find out what was going on.

The other less senior political officers and I did, in fact, continually try to push upon the higher-ups in the embassy the importance of giving greater credence to the new black leaders, and to push American policy toward a more equitable stance, and to press the South Africans to more reasonable policies. It wasn’t that the embassy top leadership supported apartheid in any way; they didn’t, of course. But, by virtue of their age, or their experience, or their professional standing, or greater commitment to reflect the carefully balanced U.S. policy, or whatever, they were just more restrained and more careful. In some ways, that translated to us a position that wasn’t sufficiently anti-apartheid.

I remember at one point we had some internal dissent concerning a visit to South Africa by Henry Kissinger, who was secretary of state then. . . He was coming to see the government leaders and this was really just a token meeting with blacks. Three of us in the political section – there were only four officers the political section, the counselor and three younger officers – were aghast when we saw this list of black leaders, which was a list of very nice people but didn’t include people from the emerging leadership, nobody who we considered among the real, more credible leaders of black South Africa. . . I remember the three of us writing a joint memo to the ambassador telling him we were unhappy with the choice of participants in the meeting. He took it seriously enough to meet with us and ask for names of people that Kissinger ought to meet with. It was kind of tough for us.

***

Aaron Williams

South Africa—USAID Mission Director

Read Aaron Williams’ full oral history HERE.

“We had a major program to support historically black universities in South Africa.”

Improving Education, Improving Opportunities:

Q: I know you were supporting some of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities in South Africa. And was part of that program to link them to American institutions, or—

WILLIAMS: Yes, it was. We had a major program to support historically black universities in South Africa. And this a period of time when two trends were quite obvious in the higher education sector. The major white universities in South Africa were starting to recruit heavily top students from the historically black universities in South Africa, which was obviously both progress and at the same time a controversial issue. They were also hiring top black faculty. So a brain drain was underway from the historically black universities to the prestigious, leading universities, such as Wits, and the University of Cape Town.

So our job was to support the local HBCUs, by training faculty and providing scholarships. We also identified overseas visiting faculty to serve as professors in the historically black universities. . . And we also had a partnership with the American HBCUs who partnered with the local HBCUs under the TELP project: Tertiary Education Leadership Project.

The only major contentious issue was the battle over whether or not we should fund a new medical school in South Africa that would be for the black community. And that was a tough battle. I saw the merits of the case, but didn’t have the funding to support this venture. However, the leaders of that initiative were determined to secure USAID funding by any means necessary.

So they enlisted former Governor Doug (Douglas) Wilder to bring their case to the U.S. Government. And he was very persuasive, because he had access to President Clinton, Vice President Gore, Brian Atwood, et cetera. It was decided that during the BNC’s next meeting in DC, that I would meet with Doug Wilder to explain our views on this new project. So we met at Wilder’s law offices, and it was a very interesting meeting . . . There was a lot of mutual respect, and I think the Governor was very open-minded, saw both sides of this issue and resolved it in a very satisfactory way.

“TS [Takalani Sesame]has been praised for its powerful contribution to preschool education, and positive impact on millions of children.”

Focusing on Youth: There is another example that demonstrates the importance of such support, and this was the Sesame Street initiative. We had entered into a partnership with the Children’s Television Workshop to create a local version of Sesame Street, as a co-production with South African Broadcast Company (SABC). This program was envisioned as part of our pre-K education program . . . However, this initiative ran into high profile opposition from Senator Jesse Helms, then the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It would take a novel to retell this story in full, but suffice it to say that Sesame Street was under attack because it was part of the PBS family in the U.S., and this U.S. domestic battle was extended to the shores of South Africa, including several harsh press stories about me and my colleagues. As I often said during this period: “Who could be against Big Bird,” but clearly SABC was concerned about this level of international criticism. Nevertheless, every step of the way, as Michelle proceeded to finalize the project with both SABC and other local partners, Ambassador Joseph and Administrator Atwood were steadfast in their support for this important initiative.

We prevailed, and as a result, South Africa’s “Takalani Sesame,” had a 15-year run as one of the most popular children’s shows in the nation. TS has been widely praised for its powerful contribution to preschool education, and positive impact on millions of children.