For many Latin American states, expropriation has been a hammer in the toolbox of land or labor reform. For the United States, expropriation has been a thorn in the side of its companies’ profitable operations in the region—and, therefore, a threat to its interests.

This conflict has played out many times throughout the region. In 1938, the Mexican government expropriated the oil industry under Article 27, which specified the state owned all natural resources; the Roosevelt administration responded with a boycott of Mexican products. In 1952, Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz enacted Decree 900, which expropriated the land that the United Fruit Company (UFC) had laid fallow; the Eisenhower administration, with close ties to the UFC, overthrew the Árbenz government two years later. And in 1962, the Cuban government expropriated substantial U.S. landholdings, compensated at the declared tax value of the property. However, U.S. companies, who had artificially lowered prices to pay fewer taxes, cried foul that the Cuban government would not pay them the fair market price for their property. As a result, Congress passed the Hickenlooper Amendment to withhold U.S. aid from countries that expropriated U.S. property “without just compensation” the same year.

A long saga over the International Petroleum Company started when Peruvian President Fernando Belaunde Terry initiated a set of on again, off again negotiations with the company over two disputed oil fields in 1963. That saga culminated in 1968 when military dictator Juan Velasco Alvarado overthrew Belaunde for being too soft on the company and expropriated its assets in 1968. Throughout it, the threat of the Hickenlooper Amendment hung over the events, even though the U.S. Embassy in Lima felt reluctant to use it, fearing it would damage relations with Peru and undermine the Alliance for Progress, then a top foreign policy priority. Deputy Chief of Mission Ernest Siracusa remembers the whole saga from start to finish, as his career in Peru coincided with the saga’s prime years.

Siracusa served as DCM in Peru from 1963 to 1969. He became U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia as the saga wound down; he also served as U.S. Ambassador to Uruguay from 1973 to 1977, when he retired.

Siracusa was interviewed by Hank Zivetz starting in June 1989.

Read Siracusa’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Kendrick Foster.

Excerpts:

“[Belaunde] would tirelessly and eloquently expound his theories to all visitors, illustrating with elaborate mockups in full relief.”

Initial High Hopes: Belaunde was a very attractive, educated and sensitive man; an architect, a dreamer, a builder, an intellectual and a wonderful person. He always seemed to me out of place as a politician (somewhat like my feelings for Adlai Stevenson), even though he headed his own party, Acción Popular, made up mostly of young, aggressive nationalistic and leftist intellectuals and political activists.

Belaunde’s great dream was his trans-Andean highway project, along the lower eastern slopes of the Andes on what he called the “eyebrow of the jungle.” Here, he was convinced, was where Peru’s future lay and he would tirelessly and eloquently expound his theories to all visitors, illustrating with elaborate mockups in full relief. Belaunde was of a very good, upper class family, well off, but not big rich or part of the so-called oligarchy. (His uncle had served with distinction for many years as Peru’s Ambassador to the UN and once, I believe, President of the General Assembly. When he died in New York, the U.S. showed him the unusual honor of flying his remains to Peru on a special military flight ordered by President Johnson.

In any case, Belaunde was enormously popular as Peru thus emerged from many years of dictatorship — really since the Odria coup of 1948 — and there was much hope that with the help of resources potentially available from the Alliance for Progress, the World and Inter-American Banks, the International Monetary Fund, etc. and with expanded foreign investment, an era of progress and growth might well be at hand. Also, by the time I arrived, Ambassador [John Wesley] Jones had established a fine working relationship with the new President, a relationship of genuine friendship and mutual respect which was to continue unblemished, in spite of the difficulties which arose, during the five years Belaunde was President.

“Belaunde’s ill-advised promise, setting a deadline for himself on a problem which had been intractable for decades, set the tone for everything that happened in the next five years and led, ultimately, to his overthrow by the military.”

Stirrings of Trouble: The seeds of ultimate disaster were sown by Belaunde when, in his inaugural address on July 28, 1963, he promised that within 90 days he would solve the long-standing, bitter and emotional dispute between Peru and the International Petroleum Company (a subsidiary of Esso) over the oil fields of La Brea y Parinas in northern Peru. The dispute over IPC’s title to these lands dated back to the last century and though submitted to arbitration by the King of Spain, his award, handed down in 1905, settled nothing as emotional and nationalistic feelings opposing any foreign ownership of natural resources, especially oil collided with the legal rights which IPC firmly believed it had and with its willingness to defend them by all means at its disposal.

The policy of the powerful El Comercio newspaper to fan the flames with unrelenting incendiary attacks of any kind was a strongly contributing factor in the controversy. Also, the implacable animosity between the patriarch of the Miro Quesada family, owner of El Comercio, and Pedro Beltrán, ex-Prime Minister and owner of La Prensa newspaper, merely fanned the flames as Beltrán’s efforts to treat the matter at least with some degree of journalistic ethics led to charges and counter charges reflecting on the honor and patriotism of one or the other in this aspect. IPC was unfortunately caught in the middle.

The reality of such an issue was that no one in Peru would speak up for IPC no matter the integrity of its rights and actions, except, perhaps, its higher-ranking Peruvian officials. It was truly a no-win situation for the company counseling every effort to seek a fair solution, and on the whole I believe it really tried.

Belaunde’s ill-advised promise, setting a deadline for himself on a problem which had been intractable for decades, set the tone for everything that happened in the next five years and led, ultimately, to his overthrow by the military. Ironically, this came only weeks after he had, at last, reached a definitive settlement with IPC which did restore Peru’s full sovereignty over the disputed territory and reserves and promised much needed new investment.

“So with these menacing possibilities in the background the U.S. and the Embassy sought to do all it could to keep Belaunde from tripping over the trap — the 90-day settlement pledge — which he had set for himself.”

The United States Becomes Involved: The American Embassy was involved; here we were starting off with a new, democratically elected government in an important Latin American country with which we wanted to have very strong and constructive relationships under the Alliance for Progress. (After all, there were not that many democratic governments in Latin America at the time, and Peru could serve as a model.) We had a large and growing Peace Corps contingent to work at the level of the people of lowest standing, and we saw only two things which could possibly thwart our efforts to maybe make a showcase of Peru; on the one hand was the IPC case and on the other the territorial waters fisheries dispute. Peru, Ecuador and Chile had joined to assert their novel doctrine of sovereignty over the adjacent seas up to 200 miles while our firmly held doctrine was the traditional 3-mile limit asserted by maritime powers for centuries.

The reason that these two cases were so important in the context of U.S. objectives at the time was that either was capable of triggering punitive U.S. foreign aid “amendments” which could cut off all of our assistance, which we hoped might make Peru a model country for progress under the Alliance for Progress. The Hickenlooper Amendment, for example, would require in exactly six months the cutoff of all U.S. assistance in the event of an expropriation without compensation — i.e., confiscation — and this would include not only Alliance for Progress aid but also special quotas under the Sugar Act, which were of real benefit to Peru. Likewise, the U.S. would also oppose international agency loans to such a country since U.S. contributions to such agencies was very large and our vote a powerful one.

So with these menacing possibilities in the background the U.S. and the Embassy sought to do all it could to keep Belaunde from tripping over the trap — the 90-day settlement pledge — which he had set for himself.

The deadline of ninety days would expire sometime on October 28. Ambassador Jones, by the time I arrived, had set the tone of his mission there by establishing excellent relations with the President. He also had good contacts with political leaders in the Congress, with the business community, Peruvian as well as American, and with the opposition, including the Odristas, the Christian Democrats, and, discreetly even, with the APRA Party leaders as well, including [founder of the APRA Victor Raul] Haya de la Torre when he was in the country annually, (he would spend months lecturing at Oxford in England). Ambassador Jones became very popular with all concerned. He was a fine, professional, we had no better in our Service, and ideally suited for the difficult task he faced.

“However, our feeling of relief was short lived as Belaunde, for the first time of what became all too familiar thereafter, pulled the rug out from under the whole thing and shifted his position 180 degrees.”

Initial Negotiations: Our real worry was IPC. The whole five years history of that negotiation is something that I cannot go fully into here, but it was something of a never-never land tale which in retrospect seems not to have been the work of serious people. In part this reflected the often impractical and volatile personality of the President as he reacted to the multiple pressures brought to bear on him from the opposition parties, the media, the military and especially by the hot, nationalistic youth of his own Accion Popular Party.

I have no doubt that Belaunde wanted sincerely to solve this thing, but his technique was highly eccentric, often extremely so. Suddenly, for example, after long inaction he might decide he wanted to negotiate. So he would call the IPC representative and they might spend hours or even two or three days in a flurry of activity. They might even come to an agreement, with everything supposedly solved, and he would say, “We will come back at six o’clock tonight, and we will sign it.” More than once the IPC reps would report with relief such a state of affairs to the Embassy, with a lift of optimism all around.

Then, we would hear, when they went back thinking it was fine, Belaunde would present them with a totally new paper stating with a straight face something like: “What we talked about before was your proposal,” and then, presenting them with a never before seen document, would say, “Here is the final solution” and invite them to sign then and there. Hard as it may be to believe, that sort of thing or slight variation on it happened over and over again during the years of negotiations. To put the best face on it for Belaunde, who I do not believe was a duplicitous person, I would have to say that political forces having a hold on him, especially the leftist elements of his own party, were the ones who reigned him in as whatever he thought he had achieved was not seen by the opposition before his seemingly capricious reversals. (As I got to know many of these young politicians in my years in Peru it became clear to me that the only finish agreeable to them would be the complete ouster of IPC so they could not have liked Belaunde’s various “solutions.”) And there was always El Comercio and the certainty of its powerful attack on anything which did not seize IPC’s titles and investment.

But I’m getting somewhat ahead of the story and should return to the setting and events before October 28, 1963. As far as the negotiations were concerned, the Embassy was never a participant and viewed its role as that of a facilitator or intermediary, a provider of good offices to do what it could to keep the parties on the track and seeking a solution. Our overriding objective was to keep these problems from muddying the waters for the Alliance for Progress, the Kennedy administration’s premier policy for Latin America, which sought to promote accelerated economic progress and social reform in Peru as a means of serving U.S. national interests in that region. As these problems were a major threat to that aim, our role was not to become involved in the negotiations directly, but to keep prodding both sides so they would keep negotiating so the process never completely broke down.

Toward the end of the 90 day deadline, when there was much speculation as to how Belaunde would meet his promise, negotiations went into high gear, culminating at the eleventh hour, or so IPC thought, in a final accord. At the end some high officials had come from New York so as to make needed decisions on the spot. However, our feeling of relief was short lived as Belaunde, for the first time of what became all too familiar thereafter, pulled the rug out from under the whole thing and shifted his position 180 degrees. That was just before his deadline and it had other consequences affecting U.S. policy.

“Behind this “fantastic” claim, in IPC’s view, was the fine, sensationalist hand of the Miro Quesada family’s El Comercio newspaper, in league with extremists of all kinds, who had no desire whatsoever to reach a settlement and who eventually conjured up a claim so large that they could actually confiscate IPC and end up claiming further reimbursement rather than paying any compensation for its expropriation.”

ESSO Brings in a Ringer: ESSO, after the first breakdown in October 1963, sent a remarkable man to head IPC and carry out the negotiations. His name was Fernando Espinosa, a New Deal economist and one-time advisor to President Roosevelt, I understood. He had been with the Esso for twenty years and was a really fine corporate diplomat. Of Cuban birth, he spoke absolutely perfect Spanish and, notwithstanding their adversarial positions, he established a fine and respectful personal relationship with President Belaunde.

He went through all these years of absolute frustration when, sometimes for months nothing would happen, absolutely nothing at all; then, all of a sudden he would get a call from the president and they would go into whirlwind negotiations often leading to apparently real progress. Then, Belaunde might say, “Come back tomorrow afternoon, and we will put in the final touches.” Then, as too often happened, the appointment would not be kept and nothing would happen, maybe for weeks. Then Belaunde might call him back, and, as though nothing had happened before, present a totally new position. What was really going on was that every time Belaunde came up to something, his advisors would weigh-in and take it apart and Belaunde, obviously, would cave in (the dates and nature of each of these incidents is documented in the mentioned airgram).

As an example of how frustrating this was I might interject here that in the background of the pre-October 28 negotiations was a long-standing Peruvian claim that IPC owed $50 million in back taxes. The company absolutely rejected this claim but in an effort to get a solution it offered (in context of the first solution in October, 1963) to pay this amount over the life of the new contract it sought, not as back taxes, but as a premium for a new concession. Also involved was a commitment by ESSO to extensive investment in oil exploration and, hopefully development, in the trans-Andean upper Amazon region.

That early “agreement” however died aborning and, in the ensuing years, this claim for “back taxes” grew and grew until it ultimately became a claim for “unjust enrichment” which at its peak totaled about $840 million. Behind this “fantastic” claim, in IPC’s view, was the fine, sensationalist hand of the Miro Quesada family’s El Comercio newspaper, in league with extremists of all kinds, who had no desire whatsoever to reach a settlement and who eventually conjured up a claim so large that they could actually confiscate IPC and end up claiming further reimbursement rather than paying any compensation for its expropriation.

The “unjust enrichment” idea also was known as the Montesinos Doctrine after a radical professor at the Marxist Centro de Altos Estudios Militares (CAEM), a sort of officers war college which did much to indoctrinate the military with xenophobic, Marxist-influenced political and social ideas. The tragic dividend of such training became all too clear in the failed and disastrous policies undertaken by the military dictatorship which overthrew and succeeded Belaunde-Terry.

The “justification” for all this can be found in the aforementioned airgram and its enclosed or referenced documentation.

“I was sent to see Haya at Oxford in England. I met him there for tea on a Sunday afternoon, and after a long talk, in which I conveyed my understanding of the situation as best I could, Haya did promise that if such a critical point did arise, APRA would not attack the President.”

Meeting with Haya de la Torre: Through it all, the Embassy maintained contact with all elements and was in regular, discreet but not clandestine contact with APRA, the leading opposition party. At one point when Belaunde and Espinosa seemed to be close to agreement, Belaunde was afraid that APRA might viciously attack any agreement, no matter if it actually served Peruvian interests fairly. So both thought it might be useful if the Embassy could contact Haya de la Torre and try to counsel a statesmanlike, non-political attitude for the good of the country.

Espinosa conveyed this desire to the Embassy, and with the Department’s approval, I was sent to see Haya at Oxford in England. I met him there for tea on a Sunday afternoon, and after a long talk, in which I conveyed my understanding of the situation as best I could, Haya did promise that if such a critical point did arise, APRA would not attack the President, and authorized the message to be conveyed, which it later was. This [act, secret at the time] was as close as we ever came to entering the negotiations as such but in reality all we did was deliver messages. However, since that particular flurry of negotiations did not produce anything, the matter continued to drag on. Also, at another time, Walter Levy, an internationally prominent oil economist in New York was brought down to analyze the issues and perhaps give constructive suggestions to both sides. But this also was not fruitful.

The Ambassador was extremely effective in cultivating good relations with all parties; with the President and his cabinet, with all opposition party leaders, with the senior military, with journalists, and with the business community, Peruvian and American. With all of these was but one message, an appeal to support a constructive solution to this problem which could promote stronger relations between our two countries and a better future for Peru. We had reason to believe also that a solution showing respect for property rights and contractual agreements would encourage important foreign investments in Peru by interests carefully watching developments (the Southern Peru Copper Company, for example).

At one point, in order to help focus on whatever reality the numbers might contain, it was arranged for Walter Levy, a renowned international petroleum expert, to come to Peru and consult with all parties in hopes that he might see some light in the tunnel. Levy worked hard at it for some time and interviewed all concerned, but in the end, this effort came to nought as Peruvians especially showed no inclination to modify their more extreme demands.

“In typical Belaunde fashion, he waited until two nights before his deadline and then instituted unceasing, marathon, and whirlwind negotiations. Belaunde, Espinosa, and others continued in sessions for twenty-four hours and then on into the next night. At last, at dawn on [July] 13, they signed this agreement called the Act of Talara.”

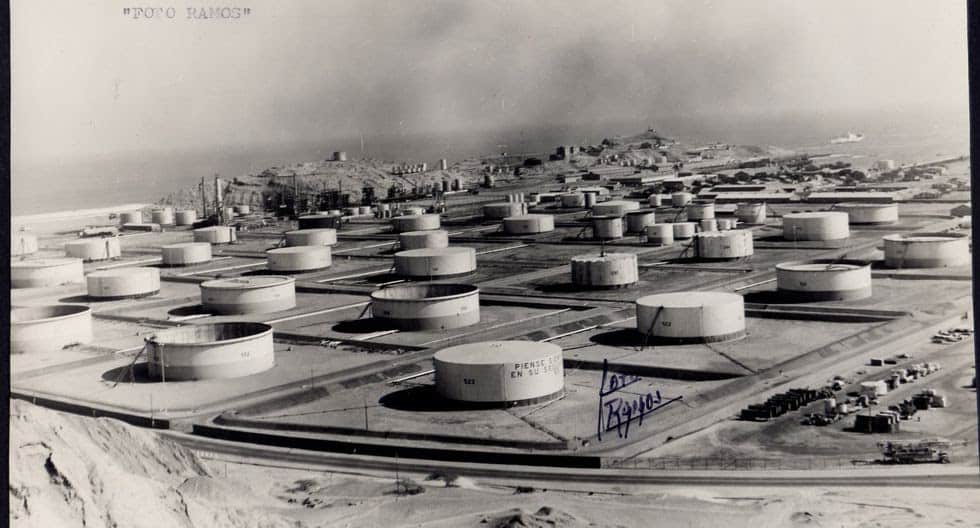

An Agreement at the Eleventh Hour: As the negotiations went on and became more complex with the introduction by Peru of new demands, Espinosa continued to show great patience and flexibility in somehow devising means of dealing with them. Finally, in July 1968, in his annual speech to the legislature on the Peruvian national day, President Belaunde announced dramatically that as a result of the latest negotiations he had an agreement. But again he put the cart before the horse and boxed himself in with a deadline as an agreement really did not then exist.

It was true, however, that there was a new basis for negotiations which showed much promise; but they had been that far before. As if to make matters worse, Belaunde then announced that on August 13 he would go to Talara to the site of the first oil well there and plant the flag, thus symbolizing Peru’s recuperation of complete sovereignty over this area.

In typical Belaunde fashion, he waited until two nights before his deadline and then instituted unceasing, marathon, and whirlwind negotiations. Belaunde, Espinosa, and others continued in sessions for twenty-four hours and then on into the next night. At last, at dawn on the 13th, they signed this agreement called the Act of Talara, which was billed as the final, ultimate solution to this problem. Then they all piled into an airplane, exhausted, disheveled, sleepy, and unshaven and went flying up to Talara.

From the airport they proceeded to the historic well site where Belaunde symbolically “planted the flag.” Then Belaunde and his accompanying ministers by turn, and even Espinosa speaking for the IPC, made emotional, happy, celebratory, and mutually complimentary speeches. I have the tapes somewhere.

“With this, El Comercio, bitter opponent of the IPC and stimulator of outrageous claims, launched a violent yellow journalistic attack which sowed suspicions and stirred up passions claiming the whole thing to be an invalid farce and sellout of Peru’s just national interests. Thus, a few days of euphoria were followed by days of dark charges of secret skulduggery.”

El Comercio Strikes Back: Back in Lima, and after catching up on their sleep, there was a series of banquets celebrating the affair. Then all of a sudden the whole thing began to unravel as one of the ministers declared that the “eleventh” page of the Act of Talara agreement a “critical” page, was missing!

With this, El Comercio, bitter opponent of the IPC and stimulator of outrageous claims, launched a violent yellow journalistic attack which sowed suspicions and stirred up passions claiming the whole thing to be an invalid farce and sellout of Peru’s just national interests. Thus, a few days of euphoria were followed by days of dark charges of secret skulduggery. A page was missing — a page was altered — needed initials to validate changes were smudged — take your choice.

It is true that the document showed real signs of its middle of the night, violent “Caesarean” birth. It was not clean and properly put together as it would have been under calmer circumstances; but insofar as we were able to determine, it was all there as intended and there were no missing pages, clauses, phrases or anything else. In a few days it exploded into an absolute crisis giving the military both opportunity and excuse to stage a coup.

“Quickly, Velasco initiated a series of ever more consequential actions which, within three weeks, resulted in an outright confiscation of the ESSO/IPC.”

The Military Takes Over: I can’t remember the exact date when it happened, but a couple of weeks later, in the middle of the night, I heard tanks rolling and went down to the Embassy. It was a quick, efficient and bloodless coup in which no shots were fired. Tanks simply rolled up to the Palace gates and took over. Belaunde was whisked away and quickly placed aboard an airplane bound for Argentina and the coup’s leader, General Juan Velasco, took over. He was to rule Peru as dictator for a number of fateful years during which the military prospered as a class (with lots of new toys and perks and pay) while the economy suffered and declined and desperate social problems were ignored.

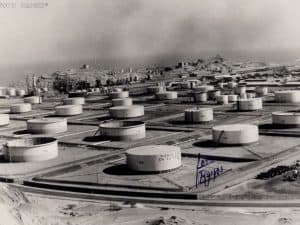

Quickly, Velasco initiated a series of ever more consequential actions which, within three weeks, resulted in an outright confiscation of the ESSO/IPC. First they just took over the La Brea y Parinas oilfields. Then they faced a dilemma because IPC’s refining and distribution system throughout the whole country was owned by the Company and was never involved in the oilfield dispute. The government could not refine or distribute any product of the wells unless IPC participated and service stations were running dry.

They then tried to sell crude oil to IPC but the company refused to buy what it said was legally theirs. To get around this crisis which was putting them in a bad light legalities notwithstanding, IPC offered to take the crude on the basis of paying for production costs but not the crude itself. Well this led to further friction and conflicts so that a couple of weeks later the army sent troops, took over the ESSO headquarters, expropriated all assets in the country and kicked all IPC executives out, including their highest ranking Peruvians.

There we were, and the fat was in the fire. From that moment on, the Hickenlooper Amendment clock began to tick. It gave us six months, from early October when it happened, until early April when, absent “prompt, adequate and effective” compensation, all aid would be cut off for Peru. For the rest of 1968 nothing happened as we marked time and wondered. The Embassy, however, began quiet planning for evacuation of Americans should the application of punitive measures produce a violently anti-American reaction, as we thought well might happen.

“Things seemed to be almost unsolvable until we uncovered a plausible delaying tactic, anything to buy time. There was a final step under Peruvian law which hadn’t yet been taken, and the Hickenlooper Amendment did not go into effect until all recourse had been exhausted.”

Faint Hopes for a Resolution Emerge: When President Nixon assumed office in January things began to move as the new administration did not want to start with a full-blown and possibly dangerous crisis in Peru. And we explored many avenues for a way to resume negotiations, but to no avail.

Finally, responding to the Embassy’s recommendation that the President send a personal representative to explore avenues of settlement, President Nixon sent Jack Irwin (later to become Under Secretary of State) as his special emissary with the rank of Ambassador. Irwin arrived in mid March of 1969 and began talks with the Peruvian government. The objective was to restore IPC-government negotiations or otherwise to avoid if possible automatic application of the Hickenlooper Amendment (which nobody wanted even though it was the law) while at the same time fulfilling US policy obligations toward an American interest which had been confiscated without compensation. In general, the executive branch of our government did not think such automatic, punitive acts such as the Hickenlooper Amendment were wise or effective law; but was nonetheless bound by them. A broadly held view was that such laws were more counterproductive than they were effective.

Things seemed to be almost unsolvable until we uncovered a plausible delaying tactic, anything to buy time. There was a final step under Peruvian law which hadn’t yet been taken, and the Hickenlooper Amendment did not go into effect until all recourse had been exhausted. This step was an Administrative Court procedure needed to finalize the expropriation in Peruvian law and which would not come up for several weeks or months. While a technicality, this could get us past the April deadline and buy time within which something good might happen. While Ambassador Jones did not think much of the chances, he presented the idea to Ambassador Irwin.

“[Nixon] was very relaxed — sat back with his feet on a coffee table — and listened to the presentation given by Ambassador Irwin, in which I participated. Finally, the president said, ‘Fine, that is what we should do.’”

Meeting with Secretary Rogers and President Nixon: Nothing better having turned up to kindle hope, Ambassador Irwin decided to return to Washington to report to the Department and to the President and he took me with him. With emotions running so high in Peru we experienced our first terrorist-type threats, phoned to the Embassy Marines, actually against my wife and children who were then evacuated from Lima for a while. Responding to this and the possible danger of commercial flight, the Department sent a special airplane to pick us up.

On Saturday morning, the day before Easter Sunday of that year, we had a meeting in the State Department with Secretary [William] Rogers and all the high officers with interest in this matter — I remember in particular the Under Secretary of State, Elliot Richardson (later Attorney General during the “Saturday night massacre” of Watergate), and Frank Shakespeare, the Director of USIA.

Ambassador Irwin outlined the situation and asked me to describe the potential means whereby we might bypass the April deadline and buy time for a possible solution. We had been told by the desk officer who met us at the airport that this proposal was not going to fly but it was all we had. In any case when I started to talk I sensed a skepticism around the table until Secretary Rogers, who was listening intently, asked a few questions indicating he might be taken with the idea. And a change in his demeanor seemed to have a magical effect on others. Finally, after much discussion, the Secretary made the decision that we should explore it with company representatives and Congressional leaders if we could find any on Easter weekend) and go the next day to present it to the President. We did see a couple of senators in addition to ESSO reps who expressed no objection.

The next morning we flew to Coral Gables to meet President Nixon at his summer residence. The president’s helicopter picked us up and took us over to a little landing pad close to his house. When we got there he was at church with his family and we were met by Bebe Rebozo, the President’s friend, who, it was said, had been partly responsible for his acquiring that property.

When the president arrived we spent two and a half hours with him. He was very relaxed — sat back with his feet on a coffee table — and listened to the presentation given by Ambassador Irwin, in which I participated. Finally, the president said, “Fine, that is what we should do.” He recognized this as a welcome time buyer and observed that we could, as long as it could be strung out, keep pressure on Peru by not approving any help and blocking that by others. The main thing was to avoid announcing that we were doing so which was the inherent defect in laws such as the Hickenlooper Amendment.

“So, what was finally worked out was that in this context, Peru did provide funds as compensation to IPC, although it was never called that. There were “painted windows on painted doors” so to speak. Everybody emerged satisfied with a solution from his perspective.”

The Endgame: So we flew back to Peru where Ambassador Irwin met with the Peruvian officials and outlined (much to their relief) what we were proposing to do, and with their understanding that the Hickenlooper Amendment was still there, but was not going to be applied at that time. The main thing I saw in this was the chance to avoid the point of no return. As long as you could keep talking you might find some way out of this.

Looking back, to condense the remainder, Ambassador Jones left Peru for his new assignment and I stayed as chargé d’affaires for the last four months of my own stay. The next key day after April when the Hickenlooper Amendment was supposed to be applied was, I think, in late July or early August of that year, when the administrative procedure should have run its course. But by that time we figured another way of stretching it out and with a new President, there was no strong Congressional pressure. Also, ESSO, knowing the U.S. had not given in on its claims and rights, also seemed willing to play for the long haul, and so no great pressure from that quarter.

I left Peru in August of 1969 and turned over the mission to Ambassador Belcher and that continued to be the policy. I went as ambassador to Bolivia after that. I was fairly close by, seeing what was going on. By one means or another the solution, if you want to call it that, stayed in place. One of the points which I had made to President Nixon was that I thought that sanctions were the worst thing in the world to apply, that they only produce terrible animosity, wounded feelings, and probably violence, and that there was no reason for us to follow a policy based on forcibly announced application of sanctions when we could do it anyway without announcing it. So we avoided the Hickenlooper Amendment. But if we avoided the Hickenlooper Amendment there was nothing forcing us to give economic help to Peru. We could still drag our feet on everything. In that way, over time we could apply pressure which would in time bring them to their senses without announcing it as a punitive act.

That is exactly the policy which was helpful. I think it was either four or maybe five years later that the problem was solved. It was worked out through the Inter-American Bank, I believe. The so-called Green Mission was sent to Peru to negotiate on potential bank loans. But there was the fact of the negative US vote because of the IPC confiscation. So, what was finally worked out was that in this context, Peru did provide funds as compensation to IPC, although it was never called that. There were “painted windows on painted doors” so to speak. Everybody emerged satisfied with a solution from his perspective. For Peru, IPC and the long-festering La Brea y Parinas problem was finally over, with Peruvian sovereign ownership fully reestablished over its natural resource. Peru could say it did not pay compensation. But ESSO had money in its pocket which it regarded as compensation and that was that; not as money as they might have wanted, but compensation nonetheless.

I think that the avoidance of the Hickenlooper Amendment at that time was a major achievement. I think that had it been applied, disastrous things could have happened in terms of American lives and property. All that was avoided. And, compensation was achieved without it.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA, Stanford University 1936–1940

Joined the Foreign Service 1961

Lima, Peru—Deputy Chief of Mission 1963–1969

La Paz, Bolivia—Ambassador 1969-1973

Montevideo, Uruguay—Ambassador 1973-1977