For U.S. Foreign Service Officers during the Vietnam War, an assignment to South Vietnam was unlike any other. For some, it was seen as a death sentence. For others, it was a chance to make a real, immediate difference in the world. For Ambassador Kenneth Quinn, it was very nearly both of those things.

After Viet Cong forces stormed Embassy Saigon during the Tet offensive, new FSOs waited with baited breath to hear if their first assignment would send them into the line of fire. At the end of A-100 (the orientation course for incoming FSOs) in D.C., newly minted Foreign Service Officers are read aloud their first assignments. With every announcement made by the course director in a packed auditorium, FSOs would applaud and cheer each post (“Oslo, Norway!” “Tokyo, Japan!”), but they had nothing but silence or whispers of “I’m so sorry,” to the new officers assigned to South Vietnam.

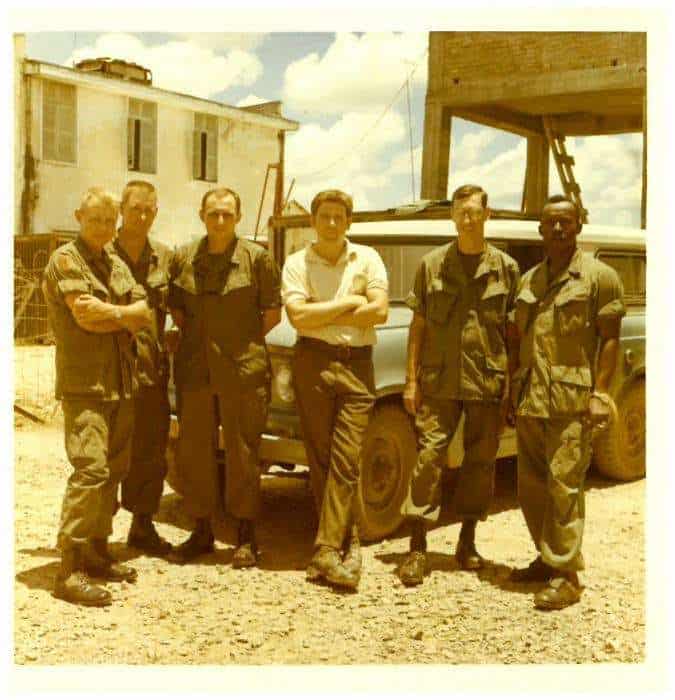

Kenneth Quinn—who would go on to become U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia—was one such young officer. He said he joined the Foreign Service with dreams of swanning about high ceilinged, chandeliered ballrooms in Vienna. Instead, his first tour of duty was to the jungles of Sa Dec Province, South Vietnam. Over the course of his service in South Vietnam, Kenneth Quinn helped to spearhead the campaign to “win hearts and minds,” led combat missions ranging from midnight ambushes to helicopter rescues, and became the only civilian during the Vietnam War to earn the U.S. Army Air Medal.

Ambassador Quinn recounts his time leading combat missions as a young FSO in this exclusive interview with ADST. For more on his role in the ideological side of the war, check out Part 2 of this series about rice, roads, and the war for hearts and minds.

For the second part of Kenneth Quinn’s moment, click HERE.

Drafted by Reagan Ashley

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts

“‘If you’re so sure they’re not VC, then let’s go down and check . . . .’ So the pilot landed.”

Last Light, K-bars, and Eagle Flights / Helicopter Combat Ops

One of the most unusual Foreign Service experiences during my career was my direct involvement in helicopter combat operations in Duc Ton District.

Our district, part of Sa Dec Province, bordered Vinh Long Province, and in Vinh Long there was a U.S. Army airfield on which two U.S. Army helicopter units were based.

One of them was the 7/1 Air Cavalry, which was known by its tactical name and call sign—Black Hawk. Our advisory team military radio at Duc Ton was linked to the command center of the 7/1st, whose radio call sign was Black Hawk 3-0, which was always said as Black Hawk “three-zero,” and never as “thirty.” They were our life line in an attack on our compound, and we were their indispensable partner in protecting the airfield.

…

To this end, the Last Light operation involved flying for an hour or an hour and a half, and using the remaining daylight available to try to find any Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Army units that might be massing together to prepare to attack the airfield once it was dark. The threat was real as the Vinh Long airfield was almost completely overrun during TET. Moreover, while I was in the Delta I saw first hand the devastating results of such an attack at the nearby Can Tho airfield. The base had been penetrated the night before by sappers who infiltrated under the cover of darkness and ran down the flight line throwing explosives on to one helicopter after another. It was stunning to see so many destroyed helicopters.

The Viet Cong forces which might similarly attack Vinh Long were all in the Y base area in Duc Ton District. The 7/1st Air Cav was assigned the job of finding any enemy force that might be planning to attack, and assaulting it to deter it. To accomplish that objective, at the end of the afternoon, one of the companies and one set of helicopters from the 7/1st would be assigned to fly what was known as the Last Light mission

The command helicopter would be a Huey which would fly out to our compound at around 5pm or so to pick up me or one of my deputies along with one of our Vietnamese counterparts, since only we could authorize any U.S. military operation in our area of responsibility

My place would be in the back of the C and C helicopter with my Vietnamese counterpart next to me, who would bring his radio so he could communicate with all the friendly troops on the ground. I was connected to all of the helicopters and back to our base at Duc Ton through the on board radio system. It was from there that I would make the decisions on where to search and whom to engage.

As we climbed in the back on the left side of the chopper, I would probably seem out of place in my usual civilian “uniform,” polo shirt, khaki slacks and combat boots. My counterpart and I sat on these little canvas seats that were bolted to the floor. Most of the time, we didn’t buckle the seat belts. We conversed in Vietnamese and some English, but communication was difficult because of the noise of the rotor blades.

Since we had the most recent intelligence about Viet Cong movements and locations, I would hand the pilot a copy of a map of the district with the areas marked out where we were going to search, where our best information indicated the Viet Cong might be. We had a short hand to describe areas on the map, such as “the base of the Y” to denote where the two main canals converged, and “De Gaulle’s nose” for a long circular tree line that jutted out from a major canal.

After reviewing the map, the aircraft commander said “Coming Up!’ The two crew members in the back would respond “Clear right” and “Clear Left,” after which the rotors started turning more rapidly and the Huey slowly rose up off the deck. Once we were about ten feet in the air, the pilot swung the nose 180 degrees and increasing the thrust pushed the helicopter forward. The choppers would slightly dip as they picked up speed rushing at rice top level away from our base. Then once clear of that area, the Huey would rise up gaining altitude and heading toward the first search zone we had identified.

Our C and C helicopter would be 50 to 100 feet off the ground circling the area to be searched, with the Cobra gun ships hovering above and the light observation helicopters, the “loaches,” just 10 feet the ground, buzzing around trying to find and flush out any Viet Cong who might be hiding in foxholes or hidden under trees.

The LOHs would be used as bait to try to draw enemy fire. Flying at treetop level, they were looking for enemy bunkers or hiding positions, trying to scare the VC and draw fire. When that happened, the Cobra gunship helicopters would dive in and attack. Flying in LOHs was the most dangerous part of the entire Air Cavalry helicopter strategy, and usually the pilots were very young Warrant Officers.

We would try to identify where the Viet Cong had hidden their sampans along the myriad canals, since that meant they would be nearby. Over time by flying with the Swamp Fox FACs, I became acquainted with how to “read” the signs of where the Viet Cong had been moving and how long ago they had been there.

Now flying at very low altitudes, I could see clearly how their small boats would cause a break in the lotus leaves that tended to completely cover the small canals. My Vietnamese counterparts and I could try to track them following these impressions and then find the places where they would sink their sampans to hide them.

Once I gave the go-ahead to search an area or tree line, If the LOHs drew fire, they of course could fire right back and the Cobras could engage immediately. But if we encountered a situation where the pilots wanted to fire on suspicious individuals, I would have to give permission before they could do so.

For example, from time to time we would come across people dressed in black out in open fields or moving on canals near populated areas. They would not appear to be armed, but it would be difficult to know for sure since a rifle could easily be hidden in a rice paddy or in the bottom of a sampan.

Most of these people were likely farmers or fishermen who were trying to eke out a living in these mostly deserted, marginalized lands in which no one was living permanently. We knew the area well, so my counterpart and I could usually discern who was threatening and who wasn’t. But the pilots, who didn’t operate in our district very often, would see these individuals moving and would say to me something like “since they are wearing black, they must be Viet Cong,” and would want to fire on them

If I thought they were farmers, I would say no. And sometimes the pilots would get mad at me for not letting them fire freely. One time a pilot said, “If you’re so sure they’re not VC, then let’s go down and check,” likely thinking I would be afraid to do so. Then I replied something like, “All right, let’s go down.” So the pilot landed. If the individual had been a Viet Cong, he could have easily shot us and killed us sitting there completely exposed.

But my counterpart and I got out of the helicopter and found out that the man was just a farmer, but one who didn’t have his government ID card with him. So we put him on the helicopter and took him back to the district compound. The poor guy probably had a hard time getting back home that night, but he was alive because I refused to let the pilots shoot him

I make the point to emphasize that never once was there what people now refer to as “collateral damage,”—casualties or deaths of innocent non-combatant civilians on any mission I commanded or my team implemented. This could happen by just firing indiscriminately so that you would kill innocent people, but we never allowed that. I felt very proud of that accomplishment.

I spent hundreds of hours of doing helicopter operations, involving over 120 separate missions. And there were times we would make contact with the enemy and be shot at. Hearing the LOH pilots suddenly shout “Taking fire” sent Adrenalin racing through your system and riveted your attention as the gun ships strained to see the enemy location and dive in. The C and C would then fly tighter circles over the incident striving to see other enemy and to guide the gun ships and the LOHs. When this happened, the Huey would tilt dramatically to one side. With the door wide open, it felt like we could easily fall out, but we never did. It was then that shots could come toward our Huey and I can recall the co-pilot saying the aircraft had taken hits.

Indeed, on one occasion, a reporter from a Maine newspaper flew along with me and wrote a feature story about the “Last Light Shoot Up” he experienced. There was a saying in Vietnam that you never felt more alive than when you were shot at and missed. I can remember that feeling, that high that sense of elation and relief.

On a few other occasions, I would be involved in directing much more extended all day pre-planned helicopter assault operations called a K-Bar (which I learned was a big hunting knife). The idea was the operation was like a deadly swift knife- thrust from the air striking the VC. In this case, we would have all the helicopters from a company (either the Cowboys or the Outlaws) from the 214th Aviation Battalion participating in the operation. We would use the “slicks” to pick up provincial level Regional Force (RF) troops and insert them deep in the Y Base Area so they could do a day-long search for the Viet Cong.

We would then circle above the operating area, prepared to call in the gun ships if contact with the enemy were made. Usually, two of my Duc Ton District Team Army advisors would accompany the unit being inserted. When we did this same type of mission with the 7/1st, it was called an Eagle Flight.

There was one particular K-Bar operation when provincial RF troops came to operate in Duc Ton. We had inserted them by helicopter into an area we identified as a likely base. It worked as almost immediately our troops confronted a large Viet Cong force. A significant engagement and firefight ensued that lasted for a full day. It was the biggest firefight in the Delta that day and the IV Corps commanding general, BG Jack Cushman, assigned the Corps reserve gunships to support us, so we would have constant coverage when the gunships from 214th had to return to Vinh Long to re-fuel.

In an effort to surround the VC force, we called the slicks back and lifted the South Vietnamese troops and re-inserted them on the other side of a canal. With this flanking movement, which was extremely complicated to coordinate and execute from the back of the C and C chopper, we appeared to have the main Viet Cong force in the District trapped.

All of our work that long day had put us in the position to deal a knock out blow to the Viet Cong. As night came, however, the South Vietnamese officers on the ground from the provincial level, who made all the operational decisions about the deployment of their troops, broke off the contact, allowing the VC unit to escape when night fell. It was an incredibly disappointing outcome after we had spent the day trapping them, but one that revealed some fundamental issues in the South Vietnamese command structure.