Life as a Foreign Service spouse is constantly evolving, particularly for Foreign Service wives. While the State Department is now having active conversations about how to best support women and families, in earlier days, women’s needs were not always considered a priority. Wives of ambassadors especially bore the brunt of this unfortunate reality.

They were expected to leave behind their careers, enter a new post with their husbands, and focus on matters such as entertaining guests or keeping up their residences (in addition to decoding the written and unwritten rules of social life). This transition was made more difficult due to the lack of clear information provided to wives by the State Department.

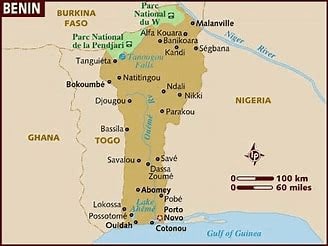

Alice McIlvaine is one such Foreign Service spouse who entered this new world with little to no formal guidance from the State Department. Upon joining her husband Robinson McIlvaine in the Foreign Service in 1961 and heading to Dahomey (now Benin), Alice immediately began to navigate her role as an ambassador’s wife. She was aided by other wives who took her under their wing, and learned new lessons constantly throughout her journey.

In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” Alice McIlvaine discusses the occasionally bumpy, and often humorous, transition into life as a Foreign Service spouse. Alice recounts her experiences getting settled in Cotonou, sharing details of odd living arrangements, entertaining, and everything in between.

Alice McIlvaine’s interview was conducted by Jewell Fenzi in February 1988.

Read Alice McIlvaine’s full oral history HERE.

Learn about her husband Robinson McIlvaine’s experiences as a diplomat in Africa HERE.

For more Moments on Foreign Service spouses, click HERE.

Drafted by Natalie Schaller

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“The girls in the State Department . . . saw to it that I had a few little briefings.”

Being Briefed:

MCILVAINE: The coming in as an Ambassador’s spouse, as an outsider was an intriguing experience.

Q: Well, intriguing because you’ve had your own career for how many years, about 15?

MCILVAINE: Oh, my goodness, about 15 years, yes.

Q: . . . and then all of a sudden there you were in Dahomey with a role to play.

MCILVAINE: . . . the role to play and a whole new world.

Q: And you did mention . . . that you got some extraordinary advice from other senior wives.

MCILVAINE: I think the old guard were quite intrigued when they had this woman suddenly coming in as Ambassador’s wife and they were very good about it. We did not have a Foreign Service Institute in those days, and they didn’t have a regular briefing program. So a couple of them got together and they arranged for me to have a few little briefings. Mind you, we were going to be married one day and heading out for our post the next, so time was of the importance.

So this really was a brand new experience. The girls in the State Department, some of the old hands, Avis Bohlen, June Byrne, saw to it that I had a few little briefings, which were pretty funny. They were giving me the grand old school . . . and I must only sit on such and such side of the car, which side I got in, which side I got out. “Whatever you do, my dear, don’t make friends with anybody but the Minister’s wife, the President’s wife. Please don’t go around with hair dressers, and things of that sort. And you must never let anyone on your staff call you anything but Mrs. McIlvaine. The servants must only call His Excellency, ‘His Excellency,’ or the various titles.”

“Of course, I got there and there was absolutely nothing.”

Arriving in, and Adapting to, Dahomey:

Nobody could tell me what to take. Nobody could tell me what the weather was like. There were no Post Reports. The State Department finally broke down and said, “Well, with great generosity, they would send a little footlocker for me.” You can imagine going out as Ambassador’s wife . . . and I had a hand bag and 44 [pounds] of luggage heading for this strange country. I remember stuffing the funniest things in—books of poetry, needlepoint, and dumb things like artificial flowers. I had a book on protocol.

Nobody briefed me on what the technical requirements were. For instance, did they provide the silver, the china, the glassware? I would write Bob and I’d say, “Bob, what should I bring?” He said, “Don’t worry, don’t bring anything. Just come on out. We’ve got everything here.” Of course, I got there and there was absolutely nothing.

Q: A bachelor’s pad.

MCILVAINE: They had supplied these funny little houses with the silver, the glass, and the china. Then we found the best way of entertaining was picnics, barbeques, dances in the garden. So, I wrote back and asked for some plastic plates and some ice coolers and things of that nature and they said, “Oh, my dear, you can’t do that. The Ambassador’s wife can’t have anything but the gold and white crested china.”

“It turned out that the French manager absolutely hated Americans.”

The French Hotel:

MCILVAINE: In the meantime, we drove through the little town which was very simple, very plain, but it did have trees, and it was on the coast. We drove up to the funny little old French hotel on the coast which would be our home. It turned out that the French manager absolutely hated Americans. We were the only Ambassadors in the country, and we were the first Americans. He had given us the worst possible room in the hotel. It was in the back, it was over the kitchen, and it was on a street. One window was on an open courtyard where they had the outdoor movies at night and all night long you’d hear the roar of the crowd as Marilyn Monroe . . . . The funny little room had a sagging bed, it had a table, it had no closet.

There was no toilet. One had to go out to the hall and down, and there in great splendor, was the public toilet with the toilet itself up several steps, and cockroaches and salamanders, and all kinds of slimy things all over the place. . . And, of course, I immediately got a disease and spent most of my time clutched in agony sitting on this throne.

Q: …wondering why you were there.

MCILVAINE: …wondering why I was there.

“It was a lot to get settled, just surviving and finding the equipment.”

Trying to Survive:

When you first arrive at a post, there is very little to do. We were in the hotel and luckily the wife of the USIS was French and she would come over on a daily basis. Then when we finally did move into our funny little house, two or three times a week I would have whatever wives happened to be there come over and we’d have some wonderful French lessons with whoever on the staff spoke French. We could all update our French. . . It was a lot to get settled, just surviving and finding the equipment.

Oh, I remember when I was going out, I asked Bob, “Should I order any case lots to be sent out?” And he said, “Oh, no, there’s absolutely everything here.” He said he had already ordered a lot before he left the Congo —he’d come from the Congo to Dahomey. He said, “It’s all here.” When I finally arrived, his cases came—he, not being an expert orderer, had ordered a dozen cans of brussels sprouts and there were a dozen cases of brussels sprouts. Somehow or other, everything else had disappeared—no, there were cases and cases of sardines.

Q: Sardines and brussels sprouts.

“Eventually a few other Ambassadors began to arrive.”

Entertaining in Dahomey:

Q: . . . You really had carte blanche to do pretty much what you thought was the right thing to do in Dahomey at the time, as far as entertaining people, or what you did because a lot of what the ladies had told you here in Washington just simply didn’t apply.

MCILVAINE: Absolutely. The wonderful instructions on “don’t make friends with the hairdresser,” were particularly inappropriate because she happened to be the niece of the president and married to a very fine old Swiss family—her husband was from a Swiss family—and she was the president’s favorite person, and a power house in that country. So you definitely wanted to make her your very best friend.

Q: Your hairdresser and your best friend.

MCILVAINE: Yes. She knew more than anybody. There was practically no protocol. I went to try and pay my calls on the foreign minister’s wife, the president’s wife, and they had never heard of an ambassador. We were the first ever there. There was no Diplomatic Corps, we were the only ones. You would go to call and they would present some woman who would receive you, but it turned out it wasn’t the Foreign Minister’s wife at all, but it was wife No. 5, who was the youngest wife who’d been educated and who had learned French, and was the one who was sent out to receive you. It was always about 10:00 in the morning and they were very much under the French influence, everything they did was influenced by the French, and many of them were educated at the Sorbonne . . . traditionally you would go in a very simple little pinout and there at 10:00 in the morning on the tray would be the champagne, the brandy, the cassis, and, of course, you’d gag and have to try and sit out one of these things in this deadly heat.

Eventually a few other ambassadors began to arrive. The French finally came. We had a German charge, and we ended up with a little group of about six or seven. But you are quite right, we could do our own style of entertaining and had to work our own way. Some of the ways I used to entertain were most amusing because we had electricity, and I remember the foreign minister’s wife returning the call was most intrigued so I spent the time letting her turn the light on and off.

“I think I really should charge the State Department for the pairs of shoes that I wore out shuffling . . .”

Just Dance it Out: There were some fabulous trips, particularly going up not too far from where we all lived which was Cotonou, going up to see the old king of Fon in his mud palace. . . One of the great highlights of any visitor’s trip was to take them to see the king and the dancers, and they would go on all day long, and each movement was less interesting than the one before—just umph- umph-umph—so this would be a long day sitting there in your mud hut watching these dancers.

Of course, dancing was another wonderful form of entertainment. They loved to dance and the weather was so hot during the day that to really give a good party, you had to have music and you had to be outdoors. I think I really should charge the State Department for the pairs of shoes that I wore out shuffling on cement school building floors, dancing with the president and the cabinet all night long.

“. . . Lots of more exciting adventures with the different, terrible things that happened in Dahomey.”

The Big Excitement, and Leaving Dahomey:

The big excitement in Dahomey . . . was finding myself pregnant there. The State Department was having a nervous breakdown because Ambassador’s wives: one, don’t get pregnant; two, I was much too old to be pregnant; and then three, what on earth are they going to do with me?

That is the story. . . at the last minute, they did call Bob and asked him to come for the promotion boards. He said, ‘‘I can’t. Alice can’t travel.” They said, “Well, you have to come.” So I had the choice of going or not going and my little local midwife said, “We’ll evacuate you. That’s how we’ll get you on the plane,” because otherwise they wouldn’t have taken me. We were changing planes in Paris when it all started, and I eventually had the baby in Paris. Then we came back and we stayed on with the small baby and lots of more exciting adventures with the different, terrible things that happened in Dahomey.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

Bachelor’s Degree, Sweet Briar College

Married Ambassador Robinson McIlvaine 1961

Cotonou, Dahomey 1961–1964

Washington, D.C. 1964–1966

Conakry, Guinea 1966–1969

Nairobi, Kenya Spouse 1969–1973

Ambassador Robinson McIlvaine’s Retirement 1973