The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is a crucial player in delivering assistance and aid to foreign countries. With a mission to reduce poverty, strengthen democratic governance, and help global communities emerge from crisis, USAID has spent the last sixty years implementing a variety of programs and initiatives to achieve such goals. One of the early programs of USAID was the Housing Guarantee Program (HG).

Responsible for providing loans for trade union sponsored projects, HG began with a specific focus on Latin American regions and the establishment of U.S.-style saving and loans associations in foreign countries. While this approach did achieve some success, under the leadership of Peter Kimm USAID’s Housing Guarantee Program developed and expanded significantly.

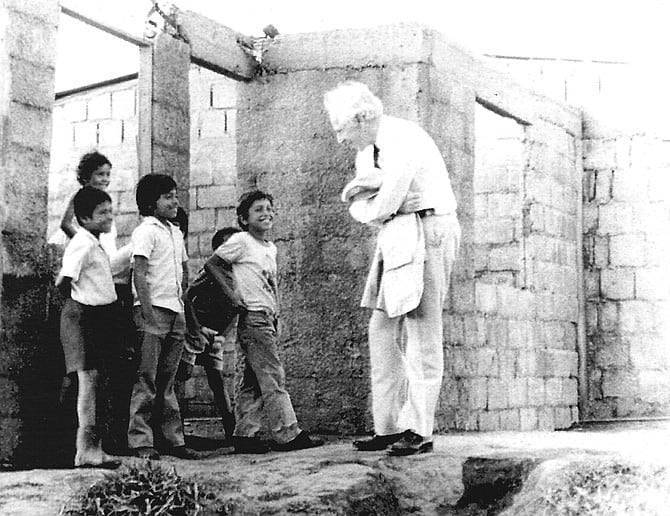

Beginning his career with USAID in 1966, Kimm first felt a call to action following President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address, which inspired him to join the Association for International Development, a volunteer opportunity with a Catholic NGO. From there, he went on to work with the American Institute for Free Labor Development, which would act as his first exposure to USAID and the Housing Guarantee Program. Through leadership, policy change, and the implementation of new legislation, Kimm helped to extend the reach of the program to not only include Latin America, but the entire globe. Simultaneously, Kimm shifted focus to upgrading urban slums into affordable housing for impoverished people in these foreign communities.

Kimm eventually moved away from the Housing Guarantee Program and stepped into other leadership positions within USAID in the early 1990s. By the early 2000s, USAID’s Office of Housing and Urban Programs and specifically the Housing Guarantee Program slowly began to lose traction and lose a significant amount of resources. Nevertheless, USAID funded numerous housing projects that ultimately resulted in an increased standard of living for local communities in locations ranging from Korea to India to various other global regions. In this “Moment” in U.S. diplomatic history, Peter Kimm highlights the evolution of the Housing Guarantee Program, the success he was able to achieve, and the threats the initiative faced that ultimately resulted in its demise.

Peter Kimm’s interview was conducted by Alex Shakow on November 17, 2018.

Read Peter Kimm’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Jacqueline Chianca

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“My new boss at AID didn’t believe that the governments of Latin America could get anything done.”

The Initial Focus of the Housing Guarantee Program:

Q: You had a lot of tangible skills yourself based on having worked in the construction industry and being very involved in development work in Latin America. Those were all things that would influence you in thinking about a career associated with international development?

KIMM: Right and particularly with those international things that were all focused on serving the poor people. Basically, Stanley Baruch, my new boss at AID, didn’t believe that the governments of Latin America could get anything done. He was unwilling to participate in a design that said that a local government was going to do this, that, and the other because he didn’t believe that they would do it. But he did believe in savings and accumulating savings and setting up a network of U.S. style saving and loan associations in any country that they could. AID’s efforts to promote saving and loan associations in Latin America in the ‘60s were very successful.

Q: For people who read this and do not know about housing guarantees and AID maybe you should clarify. Had there been this housing office from the beginning of AID or were there antecedents that go back much earlier than that? I mean, where did the notion of housing come from and what was involved? What did you walk into before you started changing it?

KIMM: At that time, The Housing Guarantee program responded directly to applications from the public. Builders would apply directly to AID. The situation I faced when I went into AID was, the office was overwhelmed with hundreds of applications and they didn’t have a system on how to process them.

Q: These applications were for getting government guarantees. This was not a cash transfer.

KIMM: Yes, not directly. What you won if you did win was a government commitment to guarantee housing mortgages. Say you are going to go and build houses in Guatemala. You get a letter from AID saying if you proceed with project XYZ, we will guarantee a loan of up to X million for that purpose. So, you get a line of credit that you couldn’t possibly get otherwise. Without the guarantee, if you had a pretty good credit rating, you could usually get one-year loans. But with a Housing Guarantee this was X which you could repay over thirty to forty years.

“By adopting such policies, the host country had the opportunity to produce millions of houses every year.”

Changes under New Leadership:

KIMM: At the time I became director, we didn’t have any field officers and the projects that were looked upon most favorably dealt with the development of savings institutions mirroring U.S. savings and loan associations. In the course of shifting our priorities, we were following pretty clear congressional instruction. The legislation indicated that they wanted the program to reach lower income people. In the beginning the program was only able to reach upper income families. So our challenge was to get our impact to lower income slum dwellers. To do that we had to come up with definitions of low-income people and we focused on how to improve the quality of life for urban slum dwellers on a sustainable economic basis. Changing policies was my idea. I wanted to run slum upgrading and infrastructure financing, programs that would help the poor people in urban slums.

Q: This gets to the question of how does this become a low-income program? Tell the story about that.

KIMM: Basically, the idea of low-income housing at real market interest rates in developing countries is unrealistic because the poor in developing countries lack the income to qualify for mortgages for complete housing units. This reality led us to switch our focus from funding individual housing projects to upgrading existing urban slums to improve the quality of life of the poor.

We got to where we had the idea of a deal between AID and host country institutions as qualification for a Housing Guarantees. That is if the host country were to stop subsidizing housing for middle-class and use that money for other low-income projects, then that would meet our goals. Our focus was on projects that provided clear title to the land, basic utilities for electricity and potable water—enhanced security improvements to existing structures and land plans that included space for schools and community facilities, and assumed that the residents would expand over time as their income rose. By adopting such policies, the host country had the opportunity to produce millions of houses every year and create related financing institutions and improved infrastructure.

“I believe the program was the victim of changing political philosophies.”

Threats to the Program:

KIMM: As we entered the ‘90s the composition of the House of Representatives changed. Under Newt Gingrich’s Republican leadership, budgets for foreign assistance were curtailed and the Republicans at that time were very concerned about our national debt; making them particularly concerned about loan guarantees and putting added pressure on AID’s Housing Guarantee Program. We fought with Gingrich. The chair or ranking member of the committee who had jurisdiction over the housing program was a Republican, Toby Roth. He hated foreign aid and was particularly against the U.S. loan guarantee programs because of their concerns with our national debt.

When I left the program, my deputy was Mike Lippe, a Harvard Law School graduate and a first rate guy. He had a great understanding of the challenges the program faced.

Q: But he was not able to carry the ball forward after you left, or do you think that the political circumstances—

KIMM: Yes, I believe the program was the victim of changing political philosophies. The program lost support among Republicans on the Hill. It also suffered a loss of some internal support within AID due to the inevitable bickering over scarce resources as resources for foreign aid were generally reduced.

“The most telling indicator of the result is the number of people who benefitted.”

The Impact of the Housing Guarantee Program:

KIMM: The impact of our program was broad and long lasting, and it received widespread recognition. The most telling indicator of the result is the number of people who benefitted. Over the life of the program over 200 guarantees were issued for a total of $3.1 billion which provided critical assistance to 30 million low income individuals in 48 countries worldwide. In addition, millions of other slum dwellers benefited from the training in the management of municipal facilities promoted by our program. I am very proud of my contribution to these truly significant accomplishments.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

Manhattan College 1948–1950

BS in Civil Engineering, The Cooper Union 1953–1958

Joined the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) 1966

USAID Housing Guaranty Program—Director 1973–1993

USAID Environmental Center—Deputy to the Assistant Administrator 1994–1997

USAID U.S.-Asia Environmental Partnership—Director 1998–2002