Prior to a long career at USAID, Frank Almaguer first gained experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in British Honduras (Belize). But he continued to work with the Peace Corps even as a Foreign Service Officer, returning to British Honduras and then neighboring Honduras as a staff member in charge of training volunteers. His years at USAID and extensive development work in Honduras set him up for one of the highest honors––serving as ambassador to Honduras in 1999.

That’s not to say Almaguer’s appointment as ambassador was in any way over-determined; it’s relatively rare for career Foreign Service Officers outside the State Department to become ambassadors. So it was fortunate that the position of U.S. ambassador, which held considerable sway in a country like Honduras, went to someone like Almaguer who had such a deep knowledge of the country. His extensive experience at USAID also made him the kind of ambassador Honduras needed at the time, as the country was still reeling from the destruction wrought by Hurricane Mitch as Ambassador Almaguer arrived.

This “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” the second in a series of Moments commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Peace Corps and the enduring connection between the Peace Corps and the Foreign Service, highlights the career trajectory of Frank Almaguer, and includes excerpts where Ambassador Almaguer recounts he and his wife’s return to Belize as part of the Peace Corps staff in 1974, his continued work with the Peace Corps in Honduras, his relations with the government of Honduras as ambassador, and his reflections on the Peace Corps––which he proudly describes as “one of the best investments the U.S. has ever made.”

Frank Almaguer’s interview was conducted by Daniel F. Whitman on January 8, 2010.

Read Frank Almaguer’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on Peace Corps volunteers who became ambassadors click HERE.

Drafted by Daniel Schoolenberg

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“Issues like water, poor sanitation outside our home, and lack of adequate support services continued to plague us—my wife in particular.”

Returning to Belize

ALMAGUER: I re-joined the Peace Corps, this time as a staff member, in October 1974. There were a couple of options, but the Peace Corps assigned me to go back to Belize, where my wife and I had served as volunteers less than five years earlier. Both my wife and I were a bit nervous about this, but our finances almost mandated a move and it was an opportunity to break into overseas work.

I was assigned to fill the position of Program and Training Officer. It was a unique situation since I would be the only American on staff. At this point, the Peace Corps was experimenting with having locals fill most positions. In the case of Belize, a small program with only some 45 volunteers, the director, Alex Frankel, was a local hire. (He was actually from Jamaica but had served as a senior officer in the Belize Government civil service for many years.) Hence, I would be in the unique position of reporting to a local employee.

It was an interesting and, in many ways, difficult 16 months (Dec. 1974–April 1976). As my wife in particular discovered, a place like Belize when one is young and unattached could be fun —challenging but not terribly difficult. However, when you have a little baby and there’s no running water for days on end—and this in the days before disposable diapers—it was particularly rough on her.

…things got further complicated at home. My wife was pregnant. While the timing was not planned, we looked forward to having a second baby. Some 10 months after arriving, we now had a baby girl, Nina, along with our 2 ½ years-old son. And issues like water, poor sanitation outside our home, and lack of adequate support services continued to plague us—my wife in particular. Amazingly, my wife opted to have that baby in Belize, which in retrospect was crazy.

Q: It was tough.

ALMAGUER: Yes it was. At that point it became evident that this was going to be too much, and so I began to inquire with the Peace Corps back in Washington. They were very understanding (I doubt a larger bureaucracy like State or USAID would have cared all that much). In the course of our few months in Belize, we had ample visits from Headquarters, including from the Peace Corps Director, and it was clear that they were pleased with the work I had been doing and eager to retain me. Early in 1976, the Peace Corps indicated that they would be willing to transfer us to a more substantive program in a larger setting —Tegucigalpa, Honduras––

Q: [Laughter] Oh boy!

––to do the same thing. I actually went first on TDY [Temporary Duty] in February 1976. When I saw the Maya Hotel near the Peace Corps office, I thought that I was being transferred to Paris.

“We also had a large program focused on social and health needs…”

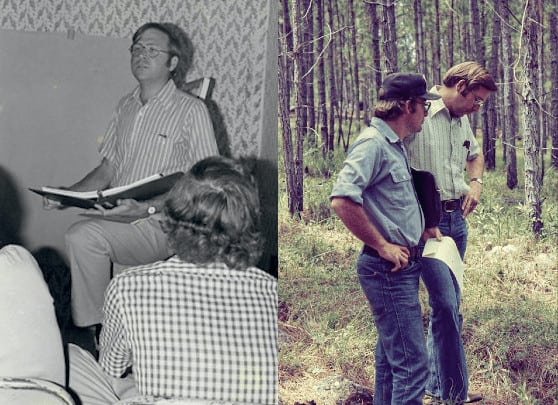

PC Staff in Honduras

We left Belize in April and, after visiting family in Miami and Albuquerque, showing off our new baby girl, Nina, and our growing son, Danny, we arrived in Tegucigalpa in May 1976. At that time (and for several years afterwards) it was the largest Peace Corps program anywhere. On the one hand, the country needed it. At the same time, it was considered fairly safe and welcoming to Americans. There was a quasi-decent hospital and more medical services than in Belize. Further, while not great, housing was far better, as well as support services from the Peace Corps and the fairly large Embassy there. Life was likely to be a bit easier for my wife and for our growing family—and, in fact, that was the case.

Q: What was the Peace Corps doing, and how effective do you think they were?

ALMAGUER: The Peace Corps in Honduras, as in many other countries, was doing a variety of things, but focused primarily around three areas: The first was agriculture at the grass-roots level —working with farmers, for example, to terrace their lands. Honduras is a hilly country, with a relative scarcity of suitable flat agricultural land, and much of the flat lands were owned and cultivated by the banana multinationals, like United Fruit and Standard Fruit, or wealthy Honduran commercial interests. Hence, terracing and improvements to protect watersheds was a big program.

Protecting forest lands—among the last remaining forest regions in Central America—was a second large program (and very much related to the work of the volunteers engaged in watershed management and improvements in agricultural practices).

We also had a large program focused on social and health needs, including the provision of basic health services, improving childhood nutrition and childhood inoculation services, as well as elementary school education.

The vast majority of the volunteers’ work was in the rural areas and designed to favor traditionally disadvantaged communities throughout the country. Our volunteers were well received and most soon learned to speak Spanish fluently—with a “Catracho” (slang for “Honduran”) accent—and to develop a taste for Honduran food and beer.

“I was ideally suited for Honduras.”

Ambassador to Honduras

In late October ’98, I was back in Bolivia, and it was about ten o’clock at night, my time, when I received a phone call at home from Skip Gnehm, the Director General (DG). He informed me that Strobe Talbott, the then-Deputy Secretary, had just finished chairing the “D” Committee… He noted that the Committee had concluded that I was as qualified as anybody under consideration and that, should I accept, my name would go forward as a recommendation from the Secretary to the White House. He added that since I had been Peace Corps Country Director in Honduras 20 years earlier, the Committee had concluded that I was ideally suited for Honduras. He asked if I would be willing to accept the nomination if it came my way after the White House considered it. I said, “Of course, I would be delighted and honored to serve.”

By a sad coincidence, on the night in late October 1998 when I received the phone call from Gnehm that I would likely be the next U.S. Ambassador to Honduras, that country was being buffeted by one of the most devastating hurricanes in 20th century history. Hurricane Mitch not only destroyed much of the infrastructure in the country and killed hundreds, but also flooded Tegucigalpa, where four days of torrential rains had caused massive landslides blocking the normal water flow. The destruction suffered by the Honduran people, along with significant destruction in nearby Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador, was a major news item for months while my nomination was churning through the Executive and Legislative gauntlets.

In the aftermath of this disaster, my nomination seemed like a fortuitous coincidence. It certainly facilitated my confirmation and the follow-up international response to the disaster shaped the first half of my ambassadorship.

My arrival in Tegucigalpa would have been big news in any case. Historically, the U.S. ambassador has played a big role in the country. Most have been well received. Both our sympathizers and our detractors (relatively few in Honduras at the time) wanted to get a “feel” for the person: “Does he speak Spanish? Is he approachable? Does know much about us?” Some (a minority) in the local media were also eager to report that “here comes the next ‘big shot’ from America to tell us what to do.” I was fully prepared for live TV cameras and a bevy of reporters at the airport.

I had hoped to focus my arrival remarks on the continuing commitment of the U.S. to help Honduras recover from the destruction brought about by Hurricane Mitch. My background with the Peace Corps and USAID was perfectly suited for that effort and my fluent Spanish made it easy to convey.

Q: So when did the President receive you?

ALMAGUER: I believe it was about 20 days after my arrival. It was a great ceremony, with some pomp, including a military band and appropriate etiquette for such solemn occasions. [President Carlos Flores] and I exchanged pleasantries and he took the occasion as an opportunity to thank the U.S. Government and the American people for the gestures of support in the aftermath of the Hurricane Mitch disaster. I shared with him that effective execution of the massive U.S. program of assistance would be my highest priority. It was in this exchange that he shared, by way of light humor, that when he learned that I had been with the Peace Corps in Honduras, he worried since, in his words, “Peace Corps people know the country better than we politicians do and it is dangerous to have an ambassador from the U.S. who knows the country and its people so well!” I took it as a compliment and, indeed, our relations after that could not have been better.

“The Peace Corps, working at the grass-roots level, has an incredible history to tell.”

Reflecting on the Peace Corps

As has always been the case with the Peace Corps experience, the volunteer ideally leaves much behind in his or her assigned community, including technical know-how and the ability to plan and organize to get things done. However, what the volunteer takes back after two years of service is of immeasurable benefit to the individual and to the U.S. In most cases, the individual, who is fresh out of college, learns a new language and learns it fluently; becomes familiar with another culture and another way of seeing the world; learns about the challenges confronting the vast majority of the world’s population; and acquires a life-long interest in their particular country of assignment and in the issues that confront less-developed societies.

The Peace Corps, working at the grass-roots level, has an incredible history to tell, in terms of the skills and work ethics the volunteers have left behind, but also at a human level. In most cases, these strangers to the community arrived, began to live much like them, did some good, and learned to eat the local food, drink the local brew, and enjoy the local games and dances. These foreigners, whom most locals assumed to be well off back in the U.S., turned out to be really nice people and, in some cases, fell in love with a local.

I cannot think of too many programs where one can say what I say about the Peace Corps. It has been by far one of the best investments the U.S. has ever made. I remain proud of my association with the Peace Corps and with the volunteers with whom I have had to honor to work, both as a colleague and as a staff member. To this day, many of the volunteers we met in Belize and, subsequently, in Honduras remain some of our closest and cherished friends. While many in the U.S. criticize the work of the State Department or USAID, there seems to be widespread acceptance that the Peace Corps is a good thing all around.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, University of Florida 1963-1967

Master’s in Public Administration, The George Washington University 1974

Peace Corps

British Honduras (Belize)––Volunteer 1967-1969

British Honduras (Belize)––Program and Training Officer 1974-1976

Tegucigalpa, Honduras––Program and Training Officer, Country Director 1976-1979

Joined the Foreign Service 1974

USAID Panama 1979-1983

USAID Ecuador 1986-1990

USAID Bolivia 1996-1999

Tegucigalpa, Honduras––Ambassador 1999-2002