Thomas Hull was undaunted by Sierra Leone’s reputation as “the white man’s grave” when he set out as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1964. After all, he was seeking an adventure––but he ended up coming away with a much deeper understanding of the country and its people. This experience afforded him insight that would serve him well in the Foreign Service, including an essential understanding of the challenges facing people in the country and the continent at large, as well as knowledge of how U.S. embassies operated through his relationships with people there, and even a slight notion of what kind of ambassador he himself would someday like to be––which he would, in 2003.

This Moment in diplomatic history includes some excerpts from a larger and more fruitful recollection of Ambassador Hull’s time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Sierra Leone, and how that set him up to eventually be the U.S. ambassador to the country many years later. Also included is a sampling of some of the aid projects Ambassador Hull was able to implement for Sierra Leone, which had only just emerged from eleven years of civil war.

After Ambassador Hull retired from the Foreign Service, he joined the board of directors of the Friends of Sierra Leone, where he completed one final project he had started as ambassador––an agreement re-continuing the Peace Corps Sierra Leone program, the first time since 1994.

Thomas Hull’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on January 23, 2004.

Read Thomas Hull’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Daniel Schoolenberg

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“Sierra Leone which is also known as the white man’s grave.”

Peace Corps Volunteer (1970–1972)

HULL: I was really surprised that the Peace Corps invited me to join and subsequently––

Q: Surprised?

HULL: Well I didn’t have any international background. I was an undistinguished student and so forth. But anyway I had the good fortune that they said here is a live one who we can send to Sierra Leone. Of course like anybody being sent to Sierra Leone in those days nobody knew where in the world it was. You grabbed the Encyclopedia Britannica in those days. First the map and then the Encyclopedia Britannica where the first sentence said, “Sierra Leone which is also known as the white man’s grave.”

Q: Because of the malaria, right?

HULL: Because of the malaria in the colonial era had killed, that means missionaries, colonial administrators did not last very long. Everybody who has ever served in the Peace Corps has had that same experience of having to explain to their parents why they were going to the white man’s grave.

Q: That didn’t daunt you.

HULL: It didn’t daunt me; I thought it was a great adventure. I wasn’t motivated very much by idealism. I thought it would be great if I could teach some people, but I was primarily interested in the adventure of going to Africa.

We were all very enthusiastic about what we were going to do in this new adventure. But without going into a lot of detail in the course of this I made very good friends with a fellow named Roger Cohen who was a communicator at the American embassy. He was my age and from my part of Massachusetts. Because of a little snafu in my training I ended up having to spend a week or two extra in Freetown and stayed with him in an American embassy apartment. Drove around in his American Embassy convertible. Enjoyed his air conditioner, washer, dryer… I also made lots of friends in the embassy. The DCM later became an ambassador. So did the political officer who gave me some self-help funds to build a school. So anyway, I got a lot of insight on how embassies operated and enjoyed the people in the embassy and thought this would indeed be an interesting career, and not nearly as onerous as being in the Peace Corps where we lived in a very rudimentary village level.

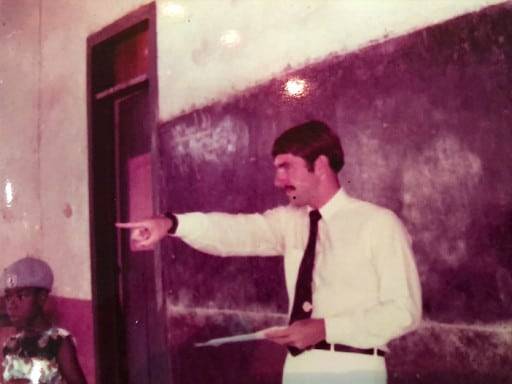

I worked as a primary school teacher, had terrific students, and to this day I stay in correspondence with some of those students. Some have unfortunately died, but again later on in life going back as ambassador, that was a tremendous asset having people who lived at the grass roots whom I could talk to and get unvarnished insight on how people were looking at the country and not necessarily through the eyes of people with vested interest in government or economic positions.

Q: We won’t dwell on whether this was idealistic or not, but it sure was very smart.

HULL: Well it was sure very useful and if it was smart, it was accidentally smart. One does not have the foresight to know one will come back as ambassador, but even when I was in the Peace Corps talking to Ambassador Miner I thought it would be interesting to come back as ambassador, to the country you served in as Peace Corps. Sometimes you can’t avoid it. People are living at impoverished levels all around you, but I think it is very hard to understand that daily struggle to survive unless you have been immersed in it.

I was happy to gain some expertise in Africa because I was interested in Africa even before I joined the Peace Corps, but I knew very little about it. But to make a very long story short, I was extremely grateful for the extreme generosity of people who lived in my village… I was really taken aback, as everybody who serves in Africa, about how generous people can be who have so little… I always felt that I wanted to give back in some way to these people who had been so generous to me. So it is one of the reasons I eventually maneuvered to go back there as ambassador when I might have gone to any other place.

“I just sent him an E-Mail saying… I would appreciate having the toughest assignment you can give me.”

Thirty-two years later––becoming ambassador to Sierra Leone (2004–2007)

HULL: I was never very much of a self-promoter and being from USIA, it was always seen as being unseemly in USIA to go out begging for jobs the way our State Department colleagues had shamelessly done in our view. So it wasn’t the sort of thing I would do. When I was the Director of Africa for USIA, if a USIA officer came to me to plead his case for a position in Africa the instinctive reaction in my mind would be what is wrong with this person that he cannot let the personnel process take its course and would emerge as the best candidate. But there were some USIA officers like that who I could name but won’t name at the moment.

Finally when it was getting close to decision time, I decided that I would bite the bullet, but rather than be so presumptuous as to call the Assistant Secretary of State, I just sent him an E-Mail saying that I hope I am not being too presumptuous, but I have all these qualifications and experience in Africa, and I would really like to be a chief of mission, and by the way I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Sierra Leone, and I thrive on tough assignments, so I would appreciate having the toughest assignment you can give me. The very next day he came back and said, “Well how would you like to be Ambassador to Sierra Leone?” which is what I was angling for anyway, even though I could have had something else.

“They assumed that because I had been a Peace Corps Volunteer… I might be more tolerant of corruption.”

Corruption

Q: …So outside of the embassy what was Sierra Leone going through at that time?

HULL: Well it was recovering from the war. The immediate postwar period was another Ambassador, mainly Ambassador Chavez. He did an excellent job. He had been an Ambassador in Malawi. He had been a Peace Corps volunteer, so he knew his way around Africa dealing with Africa. But I think West Africa is often quite different for a variety of reasons than other parts of Africa. Each region of Africa has some distinctive characteristics. Certainly in Sierra Leone, he had seen corruption in Malawi, but he had never seen corruption on the scale that you had in Sierra Leone. In point of fact, the corruption in Sierra Leone was only limited by the fact that there were very few resources to be corrupt with. So they were not as extremely corrupt, enriching themselves as other places, but corruption permeated society, the more as time progressed.

They were all very relieved to see me because they assumed that because I had been a Peace Corps Volunteer there, that I understood the country better and therefore I might be more tolerant of corruption. I think it was more my approach was a bit different. I have numerous articles headlined about talks and speeches I gave on corruption and human rights critical to Sierra Leone. What they appreciated from the outset when I gave my first remarks and I gave my Letters of Credence were accepted by President Kabbah, on corruption for example. I said “Hey I understand why corruption occurs because civil servants are not paid a living wage, but that does not excuse you for being corrupt in Sierra Leone, and we expect Sierra Leone to perform to international standards of good governance.” So they were much more tolerant of my criticism if I could show that I had some understanding of the situation, but nevertheless, there needed to be reform.

“. . . . the Peace Corps is returning in a few months in June to Sierra Leone.”

Aid Projects

One of my priorities was the restoration of the John F. Kennedy Building at the Fourah Bay College, which was the first college in all of Africa to be established back I think it was 1827, by the London Missionary Society, a largely theological institution originally. But in the 1960s, as in many places in Africa, there was an edifice established by AID in honor of our assassinated President.

This John F. Kennedy Building was there in Freetown. It was in a very bad state of disrepair. The clock had been shot out by rebel soldiers using it for target practice. It was just a disgrace and it was named after President Kennedy. It had a personal connection to me because it was the first place where I went for training when I arrived in country as a Peace Corps Volunteer. It was at Fourah Bay College that I met my wife. So this particular building had some personal significance to me as well as some significance I felt for how our country appeared to Sierra Leonians.

As I was leaving the country the project was being implemented and was soon finished to at least repaint the building and provide new desks and everything else and at least make the John F. Kennedy building look respectable once again. It was the most visible building in Freetown because it was the tallest. It sat on the mountaintop over Freetown. So looming over Freetown is this building, the John F. Kennedy building, the symbol of the United States.

One area of failure was my inability to get the Peace Corps back in the country, which had been another sign of confidence in Sierra Leone. We almost had them back. We had a Peace Corps reentry team come after two prior assessment teams. We had a person designated to be the director, and then the money didn’t materialize. But fortuitously this past year we have had the decision made, and the Peace Corps is returning in a few months in June to Sierra Leone. So even after I was Ambassador through my position on the Board of Directors of the Friends of Sierra Leone, I was able to continue to apply some pressure on this issue.

Q: I know that is a very personal thing for you.

HULL: Absolutely.

“At times I thought of joining the Peace Corps all over again.”

Post-Foreign Service Life

HULL: At times I thought of joining the Peace Corps all over again. I am not sure that my wife’s health would permit it, but I would do it individually.

Q: It would be in Africa perhaps.

HULL: Oh absolutely. It would be back at the grass roots. You know I would emphasize that we do have so many Foreign Service Officers who are former Peace Corps volunteers, and emphasize how critically important that is because of cross-cultural experiences they have had, and their understanding of life at the grass roots in a country. It is very hard when you only deal with elites to understand those elites are only the surface of a much deeper society, and the true issues of countries are the issues of the grass roots.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in History, Dickinson College 1964-1968

MA in International Education, MA in International Affairs, 1970–1972

Certificate in African Studies; Columbia University

Peace Corps 1968–1970

Sierra Leone––Volunteer 1968–1970

Joined the Foreign Service 1974

Pretoria, South Africa––Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer 1978–1980

Mogadishu, Somalia; Public Affairs Officer 1983–1986

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Deputy Chief of Mission 2001–2004

Ambassador to Sierra Leone 2004–2007