In the 1960s, the U.S. was still grappling with its new role as a world leader. For nearly two decades, it had led the effort to contain communism, combat human rights abuses, and build a stronger, freer world. However, when it focused those principles on itself, the picture became more complicated than the “Good” Free World versus the “Bad” Communists. Americans were already beginning to grow weary from the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Act was still young, and Martin Luther King, Jr. was dead. Millions of Americans were still lacking the rights to which they were entitled.

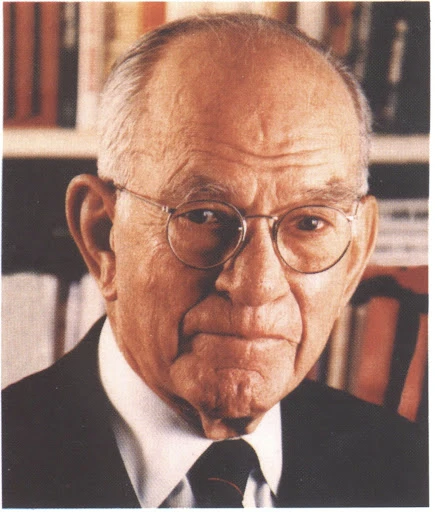

Take Senator J. William Fulbright, for example. By the late 1960s, Fulbright was one of the most influential U.S. Senators and chaired the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. He had started his namesake international fellowship, and led hearings over the conduct and practices of the U.S. in Vietnam. Fulbright had a reputation as a well-spoken, well-informed internationalist, whose leadership in foreign policy played an important dynamic in many accounts of U.S. politics at the time. However, Fulbright was also the senior senator from Arkansas, the state that had seen federal troops escort the Little Rock Nine to school. He was a signatory and editor of the infamous “Southern Manifesto,” and he repeatedly voted against civil rights legislation.

So when America’s calls for freedom and human rights were applied to its own decision makers, black and white began to mix into a confusing gray. In spite of lingering opposition, many employers, including the federal government, plowed ahead in integrating their work forces. The State Department played a crucial role in this trend, because America’s diplomats had never really reflected the demographics it represented.

The late 1960s began an important era in the State Department’s efforts to diversify. Through a program started in conjunction with the Ford Foundation, the United States Information Agency (USIA) began recruiting minority college graduates from around the country to attend graduate school at George Washington University and then enter the Foreign Service. Of the dozens of students sponsored by this program, eight eventually made the Senior Foreign Service, still years ahead of when American corporations began seeing real diversification in their board rooms and corner offices.

The USIA program was not the only push to recruit minority officers for the Foreign Service; a series of internal State Department memos dating from 1966 through 1979 demonstrated the push from the highest levels of the State Department and the Executive Branch to hire minorities. In 1966, shortly before Barbara Watson’s appointment as the first Black woman to be Assistant Secretary of State (then called Administrator of the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs), Deputy Unders Secretary of State Crockett sent a memo to all Assistant Secretaries and Executive Directors informing that all requests for new hires must be “accompanied by an indication of whether minority applicants have been given equal consideration for the position in question”.

The intention behind this new policy was to encourage bureaus to automatically include minorities in their search for personnel, and to be able to brief the Secretary of State on concrete recruiting practices focused on bringing more minority representation into the department.

Several other memos from this time period detail studies conducted by the State Department investigating hiring practices and methods of encouraging more minority applicants to the Foreign Service, tracking employees of minority groups within the department, and outlining specific requests from presidents and secretaries of State for greater minority representation within the State Department. One of these memoranda came from President Carter himself, sent to all Cabinet Officers and all Agency Heads in March of 1977. This memo read “To Cabinet Officers & Heads of Agencies: We are all committed to a continuing effort to hire strongly representative numbers of women and minority citizens. Please be prepared when asked to give me a report on this at all pay levels above GS-15.” This memo was the beginning of a series of reports compiled for Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and President Carter tracking employees from underrepresented groups in an effort to demonstrate changes in hiring practices aimed at increasing minority employment.

A standout hire from this period in State Department History is Barbara Watson, who became the first Black woman to hold the position of Assistant Secretary of State. Watson joined the State Department in 1966 under the Johnson Administration as a special assistant to the Deputy Under Secretary of State for Administration and in 1968 was appointed Assistant Secretary of State for Security and Consular Affairs. In this position she was responsible for the Offices of the Comptroller, Consular Systems & Technology, Executive Director, Fraud Prevention, Overseas Citizen Services, Policy Coordination & Public Affairs, Passport Services, and Visa Services.

Watson still faced prejudice, which fueled her motivation to promote inclusivity and diversity, instill morale in consular officers, and form important connections with political actors in Washington, DC.

Crucially, she renewed the Bureau of Consular Affairs’s image to show that an “unglamorous” job still inspired respect. In an interview with ADST on February 15, 1989, Ambassador Robert T. Hennemeyer recounted how sexist attitudes about management work perpetuated a shortage of talented consular officers. “Let’s make our wives consular officers” was a common quip, reflecting a general disregard for consular officers compared to political officers. Rather than accept the unfair status quo, Watson utilized her political skills and charisma to affirm the value of the consular corps and elevate its status.

One of her main accomplishments is establishing Consul General Rosslyn, or ConGen Rosslyn, to augment consular officers’ training regimen. ConGen Rosslyn converted a space at the Foreign Service Institute into a simulated consulate general so trainees could immerse themselves in real-world scenarios. One such scenario was having a trainee visit and assist an American citizen in a foreign jail. As a result of the unique training environment, consular officers earned greater prestige for realizing their special set of skills and management responsibilities.

Watson was also adept at solving problems while laying the groundwork for improvements. In an interview with ADST on October 9, 1997, Michelle E. Truitt, who worked as the head of Operations at the U.S. Passport Offices, expanded on Watson’s dedication to her employees. She noted how Watson expanded language training to all consular officers after learning about a gaffe at the Saudi Arabia embassy. The story goes that a Foreign Service National employee, in translating for an American citizen wanting to send an interested party cable, said “the consular officer needs a bribe.” When a political officer relayed this to Watson, she immediately took action to prevent consular officers from being embarrassed this way again.

From the State Department to Capitol Hill, Watson’s presence in a room usually drew admiration. In the same interview with Truitt, she elaborated on how Watson managed her colleagues’ prejudice with grace. As the sole woman and person of color in high-level meetings, Watson was adept at sensing whether there was discomfort around her presence. Recounting a conversation with Watson, Truitt noted how Former Secretary of State Warren Christopher was a member of a San Francisco club were Black people were prohibited, so Watson said, “When I go to see him…I plot myself right down on the couch next to him, and I show my big Black face up close to him.” Bold and unapologetic, Watson was a trailblazer throughout her career and let the fact be known.

While America continued to struggle to integrate its workforces and government, the State Department was stepping up to the challenge. Beginning with new recruiting practices in the 1960s and the appointment of Barbara Watson as Assistant Secretary of State, a new age of inclusivity was beginning to emerge. While diversification in the upper echelons of government was by no means complete, and continues to face challenges to this day, these important first steps show a dedication that was lacking elsewhere in America at the time.

Read the Moment about Barbara Watson’s career HERE. For more Moments on women pioneers in the Foreign Service, click HERE.

Drafted by Calvin Heit, Linda Li, Sophia Reitich, and Daniel Choi

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

AMBASSADOR ARTHUR LEWIS was a recruiter for USIA in 1967, and was in charge of a new initiative to recruit minority college graduates to the Foreign Service. His interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on September 6, 1989. Read his full oral history HERE.

“In 1966-67, the Foreign Service, both of State and USIA, was making a historic effort to make the Service more representative.”

New Efforts:

In 1966-67, the Foreign Service, both of State and USIA, was making a historic effort to make the Service more representative. It was looking for both junior (entry-level) personnel, but also mid-level candidates. I fell into that latter group. I came to Washington and talked to State and USIA. I finally decided that USIA was where I wanted to go because the role of USIA appeared to call for greater interaction with foreigners, rather than the more contemplative approach of the State Department. That too was the reason I chose USIA rather than State.

Q: What training or preparation did you receive as you entered the Service? How well did you feel you were served by the introductory program?

LEWIS: In essence, there was no real training with respect to my entry into USIA. I served for a year as a recruiter. I wrote a proposal to the Ford Foundation for a very special kind of minority recruitment program. The Foundation, for the first time ever to my knowledge, joined with a public service institution to give a two million dollar grant to USIA to encourage and to bring into the Foreign Service minority candidates through the “front door” rather than the “back.”

The program consisted of my seeking out bright young minority students who were graduating from undergraduate institutions. Then, we would bring them to Washington and enroll them in a very special two-year course of training at George Washington University. They would take courses in various histories and social sciences to bring them to speed. They would take the regular Foreign Service entrance examination at the end of their first year and again at the end of their second year. This was based on the assumption that they would not pass after the first year.

This program worked out very well. Of the twenty students with whom I was involved—ten the first year and the ten I chose for the second year—eleven remain in the Foreign Service today. Of those eleven, eight or nine are in the senior Foreign Service.

Q: Where did you seek these minority students?

LEWIS: I went to large public and private Universities. I went to Emory, for example, which was graduating its first two black students. I went to Tulane which was also graduating its first two black students. I got one from Emory and two from Tulane. I got some students from Berkeley, some from historically black institutions. We took ten students the first year, of whom five were black, four were Hispanic-American and one was Native American. In order to find them, I went to schools from Puerto Rico to Hawaii. We got ten students the first year, of whom eight made it through that year. The other two discovered that they were unsuited.

The peculiar aspect of the program was that I, who was not a career member of the Service, was extolling the virtues of a Service I barely knew.

AMBASSADOR ROBERT T. HENNEMEYER was Deputy Administrator of the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs under Watson from 1978–1980. His Oral History was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on February 15, 1989. Read Amb. Hennemeyer’s full Oral History HERE.

“Barbara was a very strong political leader––very charismatic in her desire to make the consular corps believe in itself and not keep thinking it was a second-class citizen in those days, and to change the perceptions of the rest of the Service, as well.”

The Battle over Consular Officers:

Barbara was a very strong political leader––very charismatic in her desire to make the consular corps believe in itself and not keep thinking it was a second-class citizen in those days, and to change the perceptions of the rest of the Service, as well. So, she wanted somebody who would relieve her from some of the management chores, and that essentially was my job.

…There was a time in the Service where it was accepted that a first-tour officer had to get that. In a way, it was a good first tour because of all the jobs in a post, it gave you the most opportunity to use your language. Second, it gave you the greatest exposure to local people. Third, it teaches you a very hard lesson that some people who have not had the experience never learn, and that is how to say “no.” So I thought there was nothing wrong with a consular tour the first time. It was rather unusual, but nevertheless, it was standard practice. I think it’s good training. But a lot of people didn’t like that, so it used to be resisted. The resistance and management’s willingness to not impose discipline resulted frequently in shortages of consular officers. People would come up with ideas about how to solve that. One of the standard ones that comes up all the time is, “Let’s make our wives consular officers. They can take care of that routine sort of work while we concentrate on high policy.” Well, you can imagine what that would do to the morale of a career consular officer who believes, rightly, that there is something very special about his work, that requires some very, very extraordinary skills, that it involves probably more management responsibility than any political officer gets to exercise. Obviously, he’s not going to like it, and you’re not going to attract good people to a Service that’s treated that way. That was Barbara Watson’s battle. I’m giving it to you in shorthand. It had many ramifications. That’s the one I helped with, despite the fact that my background was more political than consular. It was a fight that I was glad to fight in good conscience, because I thought it was a real one, the issues were real, and it was worth doing.

… I think a major contribution that was made on Barbara Watson’s watch, and which she and I strongly supported, but the credit for which belongs to a consular officer, was the creation of ConGen Rosslyn, a unique training environment and training system for consular officers, which the other functional cones are to emulate now. But I think that did more for effective training of consular officers and, hence, their prestige in the field, because the product we sent out was a better one, than almost any other innovation. That is, one of the duties of a consular officer is to visit and assist, to the extent he can, any American who finds himself in a foreign jail. Well, to emulate that, we had role playing. We actually had a small simulated jail. One of the trainees would play the role of prisoner, the other would play the role of consular officer. You would act these things out. It made it a far more realistic kind of training. The same was done with playing visa applicant and visa officer. It was a well-designed, structured, real-life training experience. It took a set of training rooms over at the Foreign Service Institute, turned them into a consulate general, and tried to emulate what really happens in a consulate general. I think it’s a very successful training program.

MICHELLE E. TRUITT was Chief of the Office of Operations at the Passport Office from 1978 to 1982. Her oral history interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on October 9, 1997. Read Truitt’s full Oral History HERE.

“When I go to see him, he is sitting on his couch. I plop myself right down on the couch next to him. And I shove my big black face up close to him.”

Facing Racism from the Secretary of State:

When Barbara Watson heard this story, she said: “We need language training for our consular officers. We cannot have our officers embarrassed in this way.” We knew that we were doing something that was on the published schedule of fees. Barbara Watson was a real major shaker in that regard. It was the first time that anyone had said that we needed language training across the board for consular officers, no matter where they were going. She also began urging Congress to appropriate funds to hold consular conferences […]

Barbara was a feminist. . . . She had it all together. Once she and Pat Derian––whom I thought was great––were at the Secretary’s weekly staff meeting. She said to Pat: “Apart from you and me, look who’s sitting around the table. Only Caucasian men.” She liked Vance. She thought Senator Muskie was excellent. She did not much like Warren Christopher. She said, “You know, Hume, I can tell right away when somebody feels uncomfortable around me. And Warren Christopher is one of those people. So, when I go to see him, he is sitting on his couch. I plop myself right down on the couch next to him. And I shove my big black face up close to him.” God bless her! I was present once when she and Christopher had a meeting. Christopher seemed almost catatonic, while Barbara animatedly filled the room. Christopher had been a member of a club in San Francisco, where blacks were not admitted.

BARBARA WATSON CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA from Barnard College, 1943

JD from New York Law School, 1962

Joined the Foreign Service 1966

Assistant to the Deputy Under Secretary of State for Administration 1966–1967

Deputy and Acting Administrator of the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs 1967–1968

Assistant Secretary of State for Security and Consular Affairs 1968–1974, 1977–1980

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia—U.S. Ambassador to Malaysia 1980–1981

Died February 18, 1983