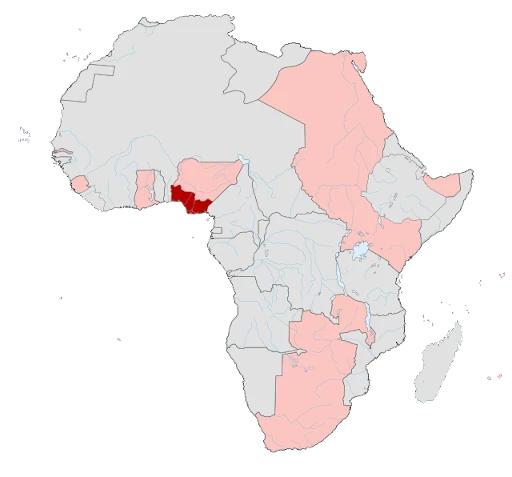

During the Scramble for Africa (a period lasting from 1881 to 1914 that brought colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers) Great Britain acquired a substantial colonial empire in Africa during the late 1800s through coerced diplomacy and military invasions. In efforts to rule the vast territory, Britain’s policies varied according to regional conditions and the nature of British settlement. In some areas, colonial officials gave local African rulers some power, while British officials controlled all aspects of society in others. In the case of Northern Rhodesia, Great Britain administered the region primarily through local African authorities. Southern Rhodesia, by contrast, saw the settlers take over themselves and gain complete political and economic control. Nyasaland, another British colony in southern Africa, did not attract as many white settlers as the Rhodesias. Still, it was home to several European-owned plantations and served as a source of labor for other colonies. Hence, Northern and Southern Rhodesia white settlers relied on Africans from Nyasaland to work on mines and farms.

Frustrated, indigenous Africans began to rebel in 1915, and revolts against colonial rule grew more robust in the 1960s. By the early 1960s, Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia’s colonial administrations yielded to the pressure and gave Africans greater participation in government. Both regions won independence in 1964 and changed the name of the countries. Nyasaland became Malawi, and Northern Rhodesia became Zambia. In Southern Rhodesia, however, the white settlers fiercely resisted any attempts to allocate power to Africans. Defying Great Britain’s request to allocate power to the majority African rule, the white minority unilaterally declared independence from Great Britain in 1965. African insurgency and nationalist groups such as the Zimbabwe African National Union and Zimbabwe African People’s Union launched an armed rebellion against the Rhodesian government, sparking the Rhodesian Bush War. Following diplomatic pressure, sanctions, and trade embargos from the United Nations, the administration’s power began to crumble. By 1980, the Zimbabwe African National Union, a majority black African government, ruled Rhodesia, modern-day Zimbabwe.

Among those pushing for desegregation were Great Britain and the labor movements. Herman “Hank” Cohen was also involved. He entered the Foreign Service in 1955 and later became an ambassador to Senegal and Gambia, worked in the Labor Department and served in several colonies such as Uganda, Kaire (modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo), Southern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe), and Northern Rhodesia (modern-day Zambia). In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” Cohen describes the impact of Labor Diplomacy throughout the decolonization stage and the calls for independence of British colonies, especially in Southern Rhodesia.

Herman Cohen’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on March 13, 2022.

Read Ambassador Herman “Hank” Cohen’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Aminata Diallo

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“They blockaded it with naval ships. The only way the whites could get in and out and get food and everything was through South Africa. The whites there were sympathetic. Okay, and then to punish them, we cut down on our diplomatic presence.”

Want to Become Independent? End Segregation First!

Q: You were in Uganda during the Cold War. At that time, some labor unions were associated with the AFL-CIO and its sister unions throughout the world. But others were affiliated with socialist parties and communist parties. Were you involved in promoting the free trade union movement?

COHEN: Yes, I was involved because we got some grant money to bring African labor union officials to the U.S. for training. In addition, we could bring some American labor leaders over to Uganda for public speaking tours.

Uganda, the University of Makerere, which was one of the first universities in East Africa. They had courses. I wasn’t directly involved in trying to keep African labor leaders within the pro-democracy camp…

Q: Now, you’re there for two years, until 1964?

COHEN: Yes. Then, I was transferred to a white minority-ruled country called Southern Rhodesia. It wasn’t as bad as the apartheid regime in South Africa, but minority rule was bad enough. Fifteen percent of the population ruled everything . . . .

In Southern Rhodesia, I finally had a labor attaché position. And this one was responsible for a region. I should note that the three countries in my region were still British colonies. Southern Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, Northern Rhodesia became Zambia, and Nyasaland became Malawi . . . .

Q: To what extent were the labor movements involved in the movements for independence and the end of segregation?

There were significant groups of workers on the railways and others working in mines. These had segregated unions—black and white. And, of course, they never talked to each other. However, I achieved a wonderful thing. I gave a reception, and I invited both of them there. And they were thrilled. That started something. But, to answer more directly, yes, in Rhodesia, Zambia, and Malawi, unions were very active in pro-independence. Well, at least as pro-independence as they could be when political parties were still authorized by the British. But in Zimbabwe, the movement for black majority rule included active support from the black unions. They were pushing for that. And there was a turning point in 1965. The white people suddenly said, “Okay, Malawi is independent, Zambia is apparently; how about us in Southern Rhodesia.”

The British said that they would not grant independence until you reform and bring about black majority rule. They would not give independence to a white minority regime. But then, the whites did not accept that. They declared themselves independent unilaterally. They even had initials—UDI, Unilateral Declaration of Independence. The British reply was that this is illegal, and they placed sanctions on the minority government. So what they did was they blocked the only independent port available to the whites, which was Mozambique.

They blockaded it with naval ships. The only way the whites could get in and out and get food, and everything was through South Africa. The whites there were sympathetic. Okay, and then to punish them, we cut down on our diplomatic presence. And I was, so they left only about two Foreign Service Officers.

That’s it. The rest of us were sent out. But I was assigned since I was a regional labor attaché, they sent me to one of my other embassies, which was Zambia. So my family and I got in the car, and we drove up to Zambia, where I resumed my labor attaché work in the U.S. Embassy in Zambia. And we had a problem there because all the automobile gasoline came from Rhodesia through that port. We were rationed, I couldn’t drive my car to the embassy. I had to take an embassy bus. And there was about a year of that. For a while, even the Americans airlifted gasoline. It was crazy . . . .

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, City College of New York 1949–1953

MA in International Relations, American University 1958–1962

Joined the Foreign Service 1955

Kampala, Uganda—Administrative Consular Officer 1962–1964

Southern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe) —Labor Attaché 1964–1965

Gambia and Dakar, Senegal—Ambassador 1977–1980

Washington, D.C.—Senior Director for Africa 1987–1989

Washington, D.C.—Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs 1989–1993