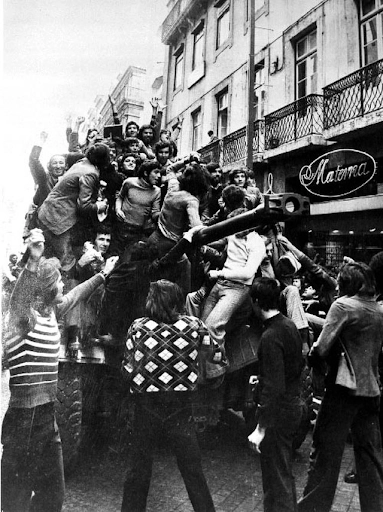

On April 25, 1974, the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MAF), composed of Portuguese civilians and military officers, successfully overthrew the fascist Estado Novo regime without firing a single shot. In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” we see that Public Affairs Officer James D. Conley, who was stationed in Portugal three years prior, witnessed every stage of this revolution and worked to cultivate Portugal’s democratic transition in the face of communism and political dissidence.

Unlike other European nations that largely withdrew their international conquests in the 1940s and 1950s, Portugal’s Estado Novo regime maintained a colonial presence into the 1960s and 1970s in the Congo, Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea. Continual presence in Africa required continual financial support. Roughly 40 percent of the annual budget went to the military instead of focusing on domestic issues such as rampant poverty and a faltering healthcare system. The Carnation Revolution ushered in significant change during the Ongoing Revolutionary Movement. After the colonial wars ended, Portugal adopted a new constitution guaranteeing fundamental rights in 1976.

James D. Conley served as a public affairs officer at the embassy and detected the buildup of political unrest before the revolt by speaking to local journalists and lawyers. He pioneered cultural exchange programs that focused on teaching English to individuals interested in hospitality and an educational training program for Portuguese teachers to bridge U.S. and Portuguese interests. Conley went on to serve in Zaire before retiring in 1978, ending a twenty-two-year career with the U.S. Foreign Service.

James Conley’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on January 27, 2000.

Read Conley’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Vishnu Dandi

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Signs of the revolution:

Q: You were the new boy on the block and when you arrived did you find that the political officers, and maybe the economic officers, were seeing that this place could blow up or were they pretty comfortable with the way things were?

CONLEY: We sensed a possible blow up because we had very good political and economic people. I will mention two names.

Wingate Lloyd was political counselor, and a gifted reporting officer by the name of Tom O’Herron, a real linguist and a political reporter who could just as well have been an ace reporter for the “New York Times.” Tom knew dissent lawyers who represented people who had gotten themselves on the wrong side of the government on various civil rights issues within Portugal. We also talked to young reporters and young military people. Around 1973 there were concerns that the country was very unstable, but no one was predicting from what corner the instability would come.

Q: Well, one does get the feeling that the Washington establishment, particularly Kissinger, became extremely concerned about the development there. Did you see a re-emergence of the communist party at this time?

CONLEY: Oh, sure. They were the only organized party. In July, I went home for an abbreviated home leave and had cabled the agency asking for an appointment with Congressman John Brademas, who had been on the Hill for 18 years. I had known John for years. I got the appointment for one reason. I thought since the communist party was the only organized party, wouldn’t it be good to provide some organizational manuals, how-to-do-it material, from both the Democratic and Republican sides in our country and make them available on a first-come, first-serve basis to any of the democratic parties back in Lisbon. That was my goal. John invited me to lunch and I explained what was going on. He said, “No problem.” When I got back to Lisbon boxes started coming in with all these organizational manuals from the Democratic and Republican National Committees. We called the fledgling political parties, who had not a clue how to organize. Their idea of effective television was a talking head. So, I got the agency to define good examples of good political television advertising. There was a collector in the United States who lived in Wisconsin who had a magnificent collection on this and the agency got it for me with the idea of showing it to these parties who had to now compete at the ballot box with one very well organized and disciplined party, the Communist Party.

Fortunately, for everybody, the communist party in Portugal was headed by a communist leader who was to the right of Joseph Stalin. He was a Stalinist in the ‘70s. His adherents tended to be inflexible, older or very opportunistic people, and ended up getting 16 or 17 percent of the vote. But, the fear back in Washington was that they were going to do a lot better than that. As I remember, Secretary Kissinger’s fear was not Portugal but the example Portugal would set for the more fragile democracies like Italy, and who knew what was going to happen at that time in Spain. Part of the problem was that the governments that were being formed in Portugal did have at least one communist as a member of the government and Portugal was a NATO country. This troubled the Department and Washington very much.

African Involvement:

Was there an emotional attachment to Africa?

CONLEY: Sure there was. The Portuguese had been there for centuries, and had a lot invested there, both emotional and economic capital. Many of the Portuguese that I knew had relatives living in Africa. They had gone there for economic opportunity and didn’t leave. They felt their purposes were noble and decent and that the world didn’t understand that. So, the Portuguese expended great sums to fly opinion makers to Mozambique and to Angola to show how they were aiding in the development of their colonies. That their policies were benevolent. It didn’t work, of course.

Q: What was the feeling? Was it that Portugal was playing catch-up in Africa? Did we feel this was a losing policy at that time?

CONLEY: Oh, I think so. By the 1970s it was a losing policy. It wasn’t a question of that policy ever succeeding. It was only a question of when they would change the policy and grant freedom to their colonies. That had to come.

Cultural Celebration:

Q: There must be a file somewhere that every time this Azores negotiation comes up is dragged out. There must be a set of speeches, demands, etc. It is always a very tough negotiation, but I think both sides realize we are going to be there. How did we feel about that?

CONLEY: I had nothing to do with the political aspects of that at all.

I just remember reading, maybe the Kennedy memoirs, where he negotiated the original base rights as a freebie so that we would have a landing field in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. As I remember we were going to negotiate in good faith to get landing rights, but if the negotiations broke down we were going to simply go in and take it. We were going to have basic rights in the Azores with or without their agreement. The Portuguese probably understood that. By the time 1973 rolled around I think there was an understanding that both sides needed to benefit from it, and that was what the negotiations were all about.

There were monies made available from us to the Portuguese for a handsome educational training program. I was the point person on that part of the result of the agreement. In fact, when April 1974 came up we were just on the verge of organizing with professors coming to town to organize a program for training Portuguese teachers, I believe, at the University of Texas. I was dealing with the minister of education and his deputy to get an agreement together.

Another example on the cultural side: the first jazz festival in Portuguese history was being held out on the coast, far enough from downtown Lisbon. There was an American group there, the Ornette Coleman Quartet. He had a bass by the name of Charlie Haden who was the only bass I know of who ever won a Guggenheim scholarship. At one point Coleman calls Charlie Haden up front from the back of the quartet and says, “I now introduce my friend and bass, Charlie Haden. He is going to go play an original composition.” Haden comes up there with his instrument and says, “My composition is called ‘Food to Che’ and I dedicate it to the freedom fighters in Angola and Mozambique.” Well, the government had suspected something like this would happen. They had no idea what it would be but that there would be an event. So, they had filled the first four or five rows with veterans from the African wars, many of them with crutches, loss of limb, etc. The huge amphitheater just went up for grabs. Charlie Haden was taken to the secret police headquarters. I got a call the next morning asking me to get him out, which I did, with the guarantee that he would leave within 24 hours. I put him up overnight and we got him out the next day. In the early ‘70s the [subject of] African wars was a tinderbox. Portugal, a beautiful secret garden of Europe with a tremendous culture and wonderful warm people, was permeated with the united policy they had towards their African colonies.

Q: Were we pushing this idea?

CONLEY: I don’t think we could, no. It was very difficult to talk to members of the opposition. One of the ways USIS’ section of the embassy was able to be helpful was the Portuguese forget politics at the door of the opera house. They are ardent opera goers and music lovers in general. So, if a musician came to be part of an opera in Portugal, I invited that person to lunch at my house where I could then invite Portuguese who represented the spectrum of thinking. They could accept even though there would be guests at my lunch table who couldn’t be at the same table in a restaurant. The ambassador would come to the lunch along with Wingate and others, so there would be an opportunity to get these people together and talk to them.

The aftermath:

Q: There is a surprisingly large group of Portuguese-Americans in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, did you find that you had senators like Senator Pell or Senator Kennedy giving a lot of attention to Portugal while you were there?

CONLEY: Senator Kennedy, in fact, embarrassed the Department. The revolution was in April, 1974 and I think it was October, 1974 that Senator Kennedy came over and met with members of the junta and announced a small aid program. It was only about $100,000 or less, but it was the first and it was coming from Congress, not the administration.

Kennedy went around and was, of course, on every front page and attracting tremendous press attention, because of who he was but also because the Portuguese were almost desperate for some signal from Washington that they supported their effort, taken at great risk, to overthrow a government primarily because of its African policy and because of the way they organized things at home, it was a dictatorship, and to free the press, free the judiciary. They thought, “Please give us a signal saying you are on our side and support those goals.” And, we were being silent. Then Kennedy came. He was the first one.

Q: Once the revolution started were we able to crank up the cultural side or were things pretty much on hold?

CONLEY: I thought we were fairly creative in what we were able to do. I started an English language program in the embassy for the Portuguese, which people expected to fall flat on its face because the British council had a long time reputation of doing a wonderful job of teaching English. But we filled a niche. That is to say, young Portuguese who wanted to get jobs in hotels, for example, we taught them how to speak English although we didn’t teach them to write well. We taught them how to understand and speak English quickly.

Q: We did that on purpose?

CONLEY: We did that before the revolution. I created what was called the American Cultural Council which was a little corporation into which the profits for teaching English after paying salaries, etc. could be used to fund cultural programs. And, we did. After the revolution, Regina Resnick, the opera soprano, was in Portugal. She had a leading role in the first opera performed in free Portugal. She became a friend. She was staying in a little hotel opposite the secret police. The only blood shed during the revolution was when the revolutionary side surrounded the secret police headquarters in downtown Lisbon and the police decided to fight and they were overwhelmed. There were two or three people killed in that skirmish. Well, CBS called saying they understood there was a building under siege and wanted to know what was going on. I said, “Well, I can put you in touch with an eyewitness who can give you an account of that. I’m sure she would love to hear from you. Her name is Regina Resnick.” “You mean the great opera star?” “Absolutely, her bedroom window looks right over the building.” Well, Regina was delighted of course because she got national exposure by giving an eyewitness account of what was going on. American artists came, pretty much on the music side, to Portugal. The exchange program went on. I was chairman of the Fulbright commission there.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political science and international relations, University of Notre Dame 1955

Joined the NSA 1955–1957

Joined USIA 1957

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1957–1959

Brussels, Belgium 1965–1968

Washington, D.C., United States, Special asst. to the USIA Deputy Director 1970–1971

Lisbon, Portugal 1971–1975

Zaire, Congo 1975–1977