“The Troubles” between Northern Ireland and Ireland date back to 1167 when England first laid roots in Ireland, but in recent history “The Troubles” refer to the 30 years of conflict over the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. The Unionist side wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom, while the Nationalist and Republican side wanted Northern Ireland to become a part of the Republic of Ireland.

Discrimination against Catholics and lack of solutions led an increase in violence and terrorism from both the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Ulster Defense Association, which led to a death toll of more than 3,600 and maiming of tens of thousands.

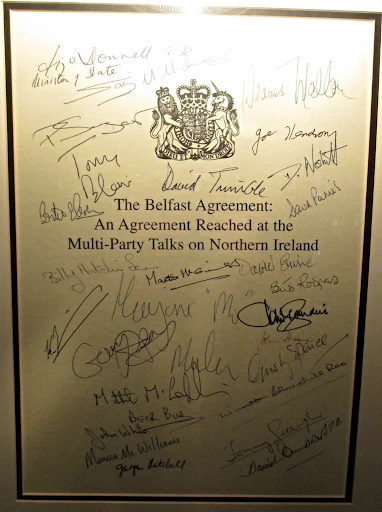

An agreement was finally reached on Good Friday, April 10, 1998. The Good Friday Peace Accords laid out a compromise that established relationships between the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom. Issues of civil rights were also central to the agreement.First, a Northern Ireland Assembly was created, with elected officials taking care of local matters. Second, a cross-border relationship between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was created to cooperate on issues. Finally, the British and Irish governments agreed to continue discussions.

Larry Colbert, Chief Consular Officer in Dublin, gives some background to the conflict and explains his frustration he encountered in trying to refuse some IRA members a visa, given that the Irish did not want to pass on information as they did not trust the FBI, which was “full of Irish-Americans.” Robin Berrington notes the IRA’s Marxist leanings and the difficulty in dealing with visiting Americans. Eleanore Raven-Hamilton talks about the dangers of working in Belfast in the 1980s while Katherine Kennedy recounts her efforts to support women legislators.

Charles Stuart Kennedy interviewed Colbert beginning in November 2006, Berrington in April 2000, and Katherine Kennedy beginning in September 2001. Edward Dillery interviewed Raven-Hamilton beginning in November 2009.

You can also read about how Berrington got into hot water with the Irish because of his Christmas letter.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

A Brief History of ‘The Troubles’

Larry Colbert, Chief Consular Officer, Dublin — 1978-1981

COLBERT: The IRA dates back in various gyrations to the 19th century under various names. In the 20th century the IRA was…[made up of] those people who did not agree to the founding of the Irish Free State and signing an agreement with the British, which lead to the founding of the state.

They didn’t agree with the terms and they thought it was a sell-out, and they then tried to undo the agreement and the so called Irish Civil War began which lasted…maybe four or five years and was bloodier than the fight against the British which preceded it.

Over time the people who opposed the Irish Free State became the opposition party and got into power under [Éamon] De Valera, and there was in term yet another — a splinter group that came into being which continued to be the armed opposition. These people who were opposed to British influence and the terms and their relationships existed on both sides of the border, the six northern counties…the northern counties and the southern counties, which comprise the republic. In both states it was considered a subversive force.

There were more IRA people in prison in the Republic of Ireland than there were in Northern Ireland, which was controlled by the British. The Provo’s, the Provisional IRA, is a split-off from the bigger IRA and it comprises the violent folks. When I was there the Provisional wing of the IRA were considered to be the fellows who were shooting the place up and robbing banks and shooting soldiers and killing policemen and so on.

“There were constant shootings, assassinations, knee-cappings”

Robin Berrington, Public Affairs Officer, Dublin — 1978-1981

BERRINGTON: [When I arrived] things were no better or worse than they had been in previous years, meaning the IRA was still in full bloom. The IRA was still very much in the business of terrorism and intimidation. Of course the Protestant extremists were equally in the business. It was very much a tit for tat.

In the three years I was there, you know, there were constant shootings, assassinations, knee-cappings. It was always very Byzantine who did it. You know, did the IRA do it to implicate the Protestants? Did the Protestants do it to implicate the IRA and make it look like the IRA had done it? Did in fact the IRA shoot their own? Did the Protestants shoot their own? Were they just shooting the other side? I mean it was more convoluted than a basket of fishes. You could never tell what was really the story.

Then in addition to that of course, occasionally the IRA would send their parties of organizers south to recruit, or in more extremist tactics, to rob banks to pay for their activities up north. Even though the south had no terrorism, there was no threat to any of us — Irish or American in the south — unless those things like forays south to rob banks or whatever would in effect contribute to a tense atmosphere regardless.

This was at the time when the British were cracking down even further on the IRA. So the things like those movements in the H Block, the prison. The called it that because it was in the shape of an “H”. The H Block where so many of the IRA prisoners were incarcerated, they would do hunger strikes. Some of them would do such things as take their own feces and spread it over the walls of their cells.

It was just a time when feelings and tensions were constantly high and it took very little of any kind of spark to set off something which usually happens about once a month or once every other month. A spark meaning something a bit bigger than your typical knee capping or shooting some guy in a bar….

“Americans had no idea the IRA and its allies were quite left-of-center”

Q: I would like to turn to the Irish American connection in terms of support for the IRA. The bars of south Boston…

BERRINGTON: Correction, not bars, pubs. Of course that was a constant problem. Because for most Americans, and you really should say Irish-Americans, because very few other hyphenated Americans contributed to NORAID, the Irish Northern Aid Committee.

For most Irish-Americans, the “Troubles” up north were a British problem. They never saw it as being an Irish problem. When I say a British problem I mean it was the British fault, the British trouble that was forcing the issue. Most Americans had a very naive idea at best and ignorant, uninformed at worst, attitudes about the IRA or any of the so-called nationalist parties that favored expelling the British and restoring Northern Ireland to the republic.

For example, the IRA, which a lot of Americans still don’t realize, its antecedents are basically very Marxist, socialist approach to government, democracy, human rights. If most Americans had known that, of course, they would have been horrified because most of the Irish-Americans that supported these causes were among the more conservative Americans here in the United States. They had no idea the IRA and its allies were quite left-of-center and quite proud of being left-of-center. They didn’t dispute that identification.

Needless to say they didn’t talk about this when they were in the U.S. “They” meaning IRA or their surrogates when they were in the U.S. NORAID and the others that raised funds in favor of these groups just, of course, played all the stereotypes and all of the anti-British tunes as loudly as they could and didn’t try to make anybody more aware of what was really going on up there.

As far as most Americans that attended these fund-raising dinners or contributed to the pubs in south Boston or whatever, the whole thing was the British oppressors and you know, the poor and suffering Irish. You would have never thought that the Irish had assassinated or shot anybody on their own. It was the British that were causing the problem. So the Americans who contributed to most of these causes didn’t really have a clue of what was going on, and despite the efforts to inform them, they did not accept this.

Of course, we the U.S. government had a very close relationship with the Irish government; we had an even closer relationship to the British government. So as far as the U.S. government image to most Irish-Americans, we were seen as part of the problem because of our close alliance with the British. So, anything on our part to try and inform or open up the issue so there was a better understanding was seen as suspect or propaganda or pro British fiction. So we were constantly dealing with this problem, the whole image of the Irish.

Q: I suppose with the visiting Irish-American Congressman and Congresswoman you would explain some of what the IRA was and all. I imagine you didn’t get very far.

BERRINGTON: Exactly. Of course the smart members of Congress, whether Irish-American or not, knew perfectly well what was going on, but for various political reasons might not have expressed this vocally in public forum, in order to retain the support of their Irish-American constituencies. They might very well sit on the fence and not really come out and criticize NORAID or the other pro IRA groups.

Others were braver and more courageous and did speak up and say, “Wait a minute, let’s really talk about what is going on here.” Of course, then you had the Irish-American businessman or you know, Joe and Jane Doe on the street who would visit their homeland. They, of course were probably among the most ill-informed and naive about what was going on. They were constantly eager to go into the embassy and talk to us and tell us so that they knew what was really going on.

Yes, one of the problems I think in an assignment like Dublin, and I hear it is not that much different in Italy or Israel or other countries where there are large second- or third-generation immigrant communities is dealing with the Americans who come back to the homeland and want to have some impact there. Particularly Ireland, the Americans tended to see Ireland in a, I don’t know if you remember the old John Ford movie The Quiet Man. That is very much a fictional portrayal, romantic kind of green idea of what Ireland is. Most Americans tended to buy that line hook, line, and sinker….

“’Don’t trust the FBI at all, it’s full of Irish-Americans’”

COLBERT: There was the party IRA, which was called Sinn Fein, and then there was the armed group, which was called the IRA. We had lists of names of people who we were not supposed to issue visas too either because they had committed crimes or because they were professional fundraisers and criminals.

What would happen would be a person coming in for a visa, and he would either be in our look-out system or more likely we would get a tip from the Irish police that he would be coming in, then take down his particulars and send a cable in to report that, say, Shane McBride, a very famous one, had come in to apply for a visa. He would apply for a visa in the south because if he applied for a visa in the north he would have to go through the British police to get to the consulate and they would probably grab him.

So he would come in and we would send in a report saying that he so and so forth and then try to get the visa office in the State Department to agree that we shouldn’t issue him a visa because he was going to do fundraising or try to get arms and all that kind of nasty stuff.

Often the State Department blinked. Their track record was so-so. They kept wanting a smoking gun. I would go over to the Special Branch, that’s to say the equivalent of the FBI in Phoenix Park [near the Dublin Zoo], because they wouldn’t come to see me, I would have to go and see them and I would take over this case.

“Yes, he is a Provo, he’s a killer, he did this, this and this. But you can’t quote us; you can’t quote me, Commissioner Hugh O’Brien.”

“Why not?”

“Well, you see if you tell them in Washington that I told you this, then I’ll get killed.”

“Why would that be?”

“Well, your FBI is just a sieve,” he said. “Don’t trust the FBI at all, it’s full of Irish-Americans, it leaks like a sieve, we don’t trust them.”

So I would have to say ‘Sources told me this persons is a bad guy.” Then they would come back and say, “We want the file. We want this.”

Then I would have to say, “Well, it’s unavailable.” They would show it to me but they wouldn’t let me send it back because they didn’t trust the FBI and that was an on-going problem. The FBI, as far as the Irish Special Branch, it was just hopelessly compromised, too many Irish-Americans who had this romantic idea about the lads. The lads were killers and thugs and they weren’t nice people at all in my humble view.

Q: Did you run across blow-hard American, Irish-Americans who would come in?

COLBERT: ….More typically you get the newly naturalized American citizens who come back as an American citizen who was originally Irish. They were much more of a challenge for me and for my FSNs [Foreign Service Nationals] and particularly for their fellow former citizens in the sense that they wanted to lord it over everybody else.

A lot of people came back looking for their roots, we had a hand-out; we didn’t do the roots thing. But people always wanted to go back and find their relatives and hopefully prove that they had done better….

“The situation was literally explosive”

Eleanore Raven-Hamilton, Consul General, Belfast 1985-1987

RAVEN-HAMILTON: Belfast, a major UK ship-building site, had been badly bombed by the Germans during WW II, and forty years later, areas around the port were still in a bad state. The situation was made worse by the sectarian conflicts and riots. There was a lot of effort to bring people together, but strife was a fact of life, and there were some bad periods of bombs exploding, riots and other violence, and heavy army and police patrolling.

The city was divided by a “peace wall” intended to keep the religious factions apart. The Belfast “peace wall” is still there, but now there are openings in it — physical openings as well as emotional ones….

When I arrived in Belfast in the summer of 1985, politicians had been struggling over next steps in the dialogue between the British government, the Irish Republic, and the leaders in Northern Ireland. There had been some steps forward, but then Prime Minister [Margaret] Thatcher had broken off the process because she felt it would compromise UK sovereignty. There was also a great deal of suspicion in some circles that the Irish government would make a grab for Northern Ireland. Not likely, I thought.

After that debacle, some very forward-looking people agreed that an Anglo-Irish Agreement was the only way to go, and the dialogue was resumed. The Irish government and John Hume, who was the head of the SDLP (Social Democratic Labour Party — basically a Catholic party), and others worked out another draft agreement, in which the British government invited the Irish government to “share in the burden of administering the troubled province of Northern Ireland.”

The Anglo-Irish agreement was signed in Dublin on November 15, 1985, by Margaret Thatcher for the UK and Garret Fitzgerald for the Irish Republic. The agreement was an umbrella agreement and was very European in structure in the sense that it was an over-arching framework agreement and not too specific.

I was Acting Consul General in Belfast at the time and hastened to report to Washington about the reaction to the agreement in Northern Ireland. This was an agreement between the UK and Irish governments, and Northern Ireland political leaders had not been involved in drafting it.

Reaction in Northern Ireland’s political parties reflected their sectarian character. The Protestants were divided. They did not want any diminution of their power in Northern Ireland. Many in the North did not like the structure of the agreement and its lack of specificity.

However, supporters of the agreement, who came from several countries and several interest groups, including churches and reconciliation groups in Northern Ireland and abroad, had helped prepare the ground for this breakthrough agreement. The Anglo-Irish agreement was the first really successful agreement between the Irish Republic and the British government, which had control over Northern Ireland (also referred to as Ulster).

Of course, Embassy London was also informing Washington, but few people from the embassy had been in Northern Ireland. There was really a dearth of interest in Northern Ireland across the UK and in the embassy too. Embassy London had a lot of other issues on its agenda with the British government.

When we asked for volunteers to come to Belfast to help out — I was acting Consul General again — and I needed help for a month, only two Foreign Service Officers, both women, volunteered. They enjoyed their two week TDY’s [temporary duty] in Belfast, but it was not on Embassy London’s regular circuit, although the Consul General in London, Ed Kreuser, used to visit us and we had a few other visitors.

I think it should have been on the embassy’s regular circuit. Northern Ireland was being governed from London, by Parliament, and the situation was literally explosive. There really were bombs going off, and there were police checks in stores and checkpoints on streets.

The British army was rolling through the streets in armored cars or personnel carriers and patrolling on foot. The army did not bring in tanks, which would have looked really bad — and would have torn up the streets too….

Northern Ireland was one of the very few places that I had ever been where no one was going after Americans. In fact, I felt fairly safe, even as a woman. My husband was working in Washington for more than half of my tour, so I was generally on my own. When I would leave dinners and drive home across the countryside late at night, I would be more worried about drunk drivers than about terrorism, but I knew there were bombs, sometimes, set along the roads, generally placed by the Irish Republican Army or one of its affiliates. One could be in the wrong place at the wrong time….

The consulate handled the various exchange programs sponsored by the United States. In addition to the usual programs, such as leader grants for travel in the U.S., there were extensive programs in Northern Ireland sponsored by American groups to bring together Catholic and Protestant young people. These young people were invited to vacation in the United States in the summer as guests of American families. Catholic and Protestant students went together to their host families in the hope that young people who made friends “across the religious divide” would help bridge that divide at home. The American hosts were so generous, and the young people were often given amazing experiences….

I got to know the leadership of the SDLP (Social Democratic and Labour Party), and I became friends with several SDLP politicians and party officials and with John Cushnahan, head of the nonsectarian Alliance Party. I also used to see Gerry Adams, head of Sinn Fein, a Catholic party, which has been linked to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), in church a lot, but we studiously avoided each other.

I used to see people from the Ulster Unionist Party (Protestant) too. I had one special contact there, who would talk to me, unlike some of his colleagues who boycotted us because the U.S. had strongly supported the Anglo-Irish Agreement from its beginnings and the Unionists were strongly opposed to it. My friend was a bit on the outs for a while with his more rigid Unionist colleagues.

Supporting Women Leaders

Katherine Kennedy 1982-1984 Belfast

Manager of the Northern Ireland Exchange Program

KENNEDY: I have been doing an ongoing project [in 2001] with a woman named Mary Boergers. She served at the Maryland state legislature for 16 years…. She is the Director of Political Management in Leadership at George Washington University. We have been doing this ongoing project with the women elected political leaders of the Northern Ireland Assembly, after the Good Friday Agreement was signed, and the local legislature of the Assembly was set up.

The Good Friday Agreement, which was signed in April, Good Friday, 1998, a political agreement that gave back political power to Northern Ireland so the people there could govern themselves. It broke the formal link of the British government overseeing Northern Ireland.

There was a legislature set up. There was an election, and people ran for what would be just like our House of Representatives….Mary having served in the Maryland legislature where there were very few women, and knowing the Irish culture, wanted to do something to support them. She wanted to help them develop as politicians and as leaders.

So, we have been doing an ongoing project and we have had representation from every political party except for Ian Paisley’s. There is a woman from his party who refused to participate in anything we’ve done. But, we have been bringing the women together from the different political parties, trying to help them build….

First of all, get to know each other as human beings. We also give them leadership training, political training; Mary does that. We have done some conflict resolution and negotiation training, and we have done stress management for them….

The growth in confidence of these women as leaders, as politicians, as individual human beings… You know, the Shin Fein IRA woman who is agreeing with the official Unionist woman publicly in front of people, representing all sectors of the community and the political divide, and their growth. The support that we have given them, and the structure that we have given them.