William E. Schaufele, Jr. was the Congo Desk Officer at State  from 1964 to 1965, when 330 people, including the staff of the U.S.consulate, were taken hostage by Congolese rebels in Stanleyville (now Kisangani). Held for 111 days, they were eventually rescued in a joint U.S.-Belgian operation codenamed Dragon Rouge. Schaufele, who later served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, from 1975 to 1977, was interviewed by Lillian Mullin on November 19, 1994.

from 1964 to 1965, when 330 people, including the staff of the U.S.consulate, were taken hostage by Congolese rebels in Stanleyville (now Kisangani). Held for 111 days, they were eventually rescued in a joint U.S.-Belgian operation codenamed Dragon Rouge. Schaufele, who later served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, from 1975 to 1977, was interviewed by Lillian Mullin on November 19, 1994.

This excerpt is taken from ADST’s Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Reader. Michael Hoyt, principal officer at the U.S.consulate in Stanleyville at the time of the takeover, describes the ordeal of the hostages in his oral history interview and his book Captive in the Congo.

“Our consulate people were taken as hostages”

SCHAUFELE: So the war went on. The advance down the Congo River by the white mercenaries was steady. The ultimate crisis came, of course, when the Simbas captured Stanleyville and our consulate. They took 330 hostages — all whites. They killed the Congolese officials in Stanleyville. Our [five] consulate people were taken as hostages…. Mike Hoyt was the acting consul…. So they were held with the rest of the hostages, including American and Belgian missionaries. The Simbas actually accused one American missionary, whose name was Carlson, of being a spy…. He was an ordained minister and a doctor. So for the first time we really became concerned about the fate of our people.

We talked with Mike Hoare [Irish mercenary, hired by the Congolese Prime Minister to fight the Simbas] and the white mercenaries and asked them if they could get to Stanleyville. If they got to Stanleyville, would they be able to take the town rapidly enough to prevent any harm to the hostages? Hoare didn’t think that that was possible….

That’s when we set up the airdrop with the Belgians. That was done when Paul Henri Spaak was Prime Minister, with Governor Harriman [and Under Secretary for Political Affairs] doing most of the negotiating. We had, not so much a difficulty, but we had to discuss how this was going to be done. The American concept for dropping paratroopers in an operation like this is a large-scale thing. The Belgians didn’t like that. In the first place, it was going to become public knowledge that much sooner. Secondly, you don’t need all of those people. So the final agreement was that the Belgians would supply the paratroopers, and we would supply the planes from which they dropped.

The Belgians supplied 300 paratroopers — that’s all they had. They would jump with little motorized tricycles. They would race right into Stanleyville on these tricycles. No armored cars or anything like that. This operation was all, obviously, “hush hush.” The Belgian paratroopers were picked up in Belgium by our planes. That was all right because Belgium is a NATO country. Then they were flown down to Africa. The planes refueled somewhere in southern France. We think that that was where one of the Belgian soldiers, who was a stringer for a Belgian newspaper, let the cat out of the bag…. The operation had not been publicized. We think that that’s where he made contact with his paper. Obviously, the Belgian papers were very reluctant to publish this story. They didn’t want to cause any trouble for their own people — and, besides, nothing had happened yet.

The next stop for the Belgian paratroopers was Ascension Island. I guess that they stayed there for a couple of days. Ascension Island is a British possession in the South Atlantic Ocean…. Then, on the following day, the Belgian paratroopers jumped on Stanleyville. There was one interesting aspect. I still kid him about it when I see him. Bruce Van Voorst of “Newsweek” came in after the jump. He said, “You lied to me the other day.” I said, “What do you mean, I ‘lied to you?'” He said, “I asked you this question.” I said, “Do you remember the question you asked me?” He said, “Well, no, not specifically.” I said, “Well, I can. You said, ‘We have a report that there are Belgian paratroops on Ascension Island. Is that true?'” He said, “Yes, and you said ‘No.'” I said, “That’s right. They’d already left.” He was kind of chagrined by that. That’s right. He should have asked the question in a different way.

So I remember the night when the paratroops dropped over Stanleyville. It happened about 11:00 PM, Eastern Standard Time. Secretary Rusk and Deputy Secretary Ball came into the Operations Center, wearing black ties. That’s another thing that I really should mention. That was the first time that I worked out of the Operations Center. It’s a lot better now, but even then, they could reach any place in the world and wake up anybody. It’s a real concept, the Operations Center. It was the military, essentially, who had developed the idea and expanded it into our embassies and consulates. It’s incredible — the reach of these people in Washington and the United States. So that took a big load off us. We could say, “Get us somebody, somewhere.” We didn’t have to do it ourselves. That can be very time consuming. As I said, Secretary Rusk and Deputy Secretary Ball arrived in the Operations Center. [Assistant Secretary for African Affairs]”Soapy” Williams and everybody else were there. At some point — I can visualize it, but I can’t recall exactly what time it was — the die was cast. There could be no further change. The Belgian paratroops dropped at the Stanleyville airport, got on their little tricycles, and raced into town. Meanwhile Mike Hoare and his white mercenaries arrived at the outskirts, though they had not gotten into town.

“There probably would have been more people killed if we hadn’t gotten there in time”

Q: But the Simbas were in Stanleyville?

SCHAUFELE: Oh, yes. They controlled the city.

Q: And that was quite a large force of Simbas at the time.

SCHAUFELE: I don’t recall how many Simbas there were. We couldn’t figure out how many there were, because they would pick up some people and drop others off. Stanleyville always was kind of a “revolutionary” town…. The Belgian paratroops raced into town, right to the place where the hostages were. We knew where the hostages were. They were concentrated in one small area — I suppose about a city block, in various buildings, surrounded by Simbas.

Q: Had their families left, or were their families there also?

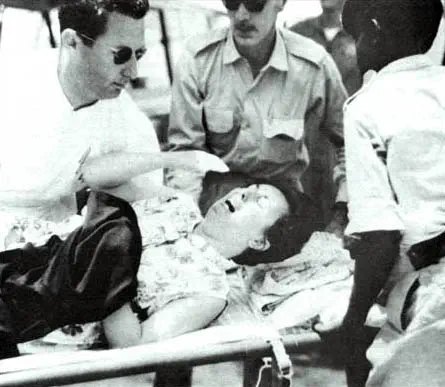

SCHAUFELE: Mike Hoyt didn’t take his family up there to Stanleyville, as he only expected to be there temporarily. However, there were missionary families there. I seem to recall…that there were 23 hostages killed. The Simbas just started firing indiscriminately. One of those killed was Carlson, the man they accused of being a “spy.” But the State Department people in our consulate were not hurt.

Q: But were they in any danger?

SCHAUFELE: Oh, yes. They were shot at, too. They ducked down behind cover and weren’t hit. I don’t think that the Simbas had any thought of sparing them. The Belgian Consul was freed safely. I don’t know how many people he had in the Belgian consulate there. So, as much as we regretted the death of any of the hostages, it was a “reasonable” operation from the overall viewpoint. There probably would have been more people killed if we hadn’t gotten there in time. The white mercenaries then came in and took control of the town.

Q: How did they get the hostages out?

SCHAUFELE: They flew them out in C-130’s, because we had dropped the Belgian paratroops from the C-130’s. The planes circled overhead until they were sure that they could land safely at the airport. They landed and took the hostages out. Two more airdrops were planned. The code name for the air drops was “Dragon,” and they had colors.Stanleyvillewas “Dragon Rouge” [Red Dragon]. Another place was “Dragon Noir” [Black Dragon], which was supposed to be in Paulis, a place which was also held by the Simbas. The Belgian paratroopers did drop on “Polis.” A few people were killed up there — not as a result of the landing. The Simbas had already killed some hostages there. The third drop — Bunia — was cancelled. It was no longer necessary. The Simbas kind of “evaporated” into the mountains. In three days the Belgian troops were back in Belgium. That’s the way that kind of operation should go. One Belgian paratrooper was killed.

Q: So the Belgians went away….

SCHAUFELE: That’s right. We tend to overdo this kind of thing. It’s like fighting the Gulf War. We take six months to gather an overwhelming force, and then the operation takes two days, or something like that. No, I think that the Belgians were right, for this kind of operation. Dropping 10,000 American paratroops who didn’t speak French or any other foreign language would not have done much good….

The Congolese government kind of reverted to their old, corrupt ways. The big thing was that President Kasavubu was dropped and Mobutu became the president. That determined the direction of events for a long time…. People would say, “Why isn’t the Congo democratic? Instead of interfering in their affairs, why don’t we let them decide by a democratic process? Let them have ‘grass roots democracy.'” In the first place, we couldn’t decide a lot of things that these people thought we could decide. The Congolese were in control of the country. Secondly, the Congo would immediately break down into their tribal groupings. You wouldn’t have a Congo anymore. You’d have a bunch of little fiefdoms. Some people find that very difficult to believe.