Michael Hoyt was Commercial Officer in Leopoldville from 1962 until 1965 and was serving as interim Principal Officer in Stanleyville (now Kisangani) when he and his staff, along with 320 other people, were taken hostage by the rebel Simbas. Held for 111 days, they were eventually rescued in a joint U.S.-Belgian operation code-named Dragon Rouge on November 24, 1964. He talks of how they had to destroy classified material and fight off the rebels at the consulate before they were taken hostage, the many times they thought they would be executed or fed to the crocodiles, the daring rescue, and the less-than-positive feelings he had toward the ambassador who ordered him to stay at the consulate. Hoyt is a recipient of the Secretary’s Award for his actions and was interviewed by Ray Sadler in 1995. These excerpts were taken from the Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Reader.

(Note: The name “Simba” comes from the fact that the tribal fighters were told by shamans that they would be immune to bullets, and would be transformed into “simbas,” Swahili for lions, when they were in battle.)

“We were busy destroying, burning, all classified materials”

Q: Did the Agency try to run an operation designed to extricate you?

HOYT: Yes. There were various designs for an operation. They thought of everything they could possibly think of. One of the operations was to drop people up river from Stanleyville and have them come down on rafts. That is until somebody pointed out to them that the reason Stanleyville existed is because it just down-river from Stanley Falls. It would have been the raft trip of the century. Stanley made it but he made it by portering around.

The [rebels] took [Stanleyville] on Sunday. Tuesday I had people evacuated. The Ambassador had said Monday night that I was to stay with the vice-consul and the communicator. So we were busy Tuesday day destroying, burning, all documents, classified material. I didn’t have very much in my files, but the CIA station had bunches and bunches of them. They burned all day. [We had] just barrels lined with incendiary material. You filled it, then lighted it. We had to keep refilling the things because we had so much material….

That evening, about 6:00 p.m., at nightfall, I got a call from the airport. It was the Air Attaché from Brazzaville, who had been sent up to help in the evacuation. “I’m here to take you out,” he said. I said, “In the first place, I’ve been ordered to stay. Secondly, I don’t think I can make it through.” The airport was on the other side of town, another mile or so beyond, and I wasn’t about to drive through that city with the ANC [National Congolese Army] about…. So this attaché said, “You guys are out of your minds, come out!” I stopped to think for a moment. I knew it was foolhardy to stay…. Actually, we ran out of time. By the that time it was dark we were stuck. I told the attaché “We’re not coming.” I heard something like “idiot” and the phone went dead. …

This is the 5th of August 1964…. It was David [Vice-consul, CIA], saying that, “I think you’d better come over here pretty quick.”… “Come now. They’re attacking.” …

“We could hear [them] outside of the vault still shooting”

So I dashed out the back. Normally the back was closed off from the consulate so that we’d have privacy. There was a swimming pool in the back yard to the residence. When we were burning everything, we tore down the fence and opened the back door to the consulate. I ran out without telling Jim, the communicator, anything. He had apparently caught on and was right behind me. I go into the back door of the consulate to the reception area. There was a burst of gun-fire, and I drop to the floor. Jim rushes by me, dives into the vault. On the floor, I saw two or three Congolese employees huddled in the corner. I said, “Come quick.” I motioned them to get into the State safe, the smaller safe. [A tight box connected the two vaults so that messages could be passed from the State side to the CIA side]. I shoved the Congolese into the small vault and closed the door and then dove into the big vault. All this time, I could hear shots being fired all around me. The others had been standing in the vault door shouting, “Come quick, come quick.” As soon as I got in the vault, they closed the door. They moved safes up against the door.

David whispered to me that he had seen a group of what he thought would be the rebels. They were dressed in ANC uniforms but with branches and stuff attached to their uniforms — furs and stuff like that. They had automatic weapons and they were firing as they came. We could hear them outside of the vault, still shooting, breaking into the front door, people stomping around and yelling and so on…. We assumed they had cleared out the employees from next door, because we heard nothing of them. We could hear them at our vault door. To hide the fact there was a vault in the room, a wooden door was installed in front of it. That was torn down and someone started firing at the door. Then the lights went out. We learned later that David’s driver had told them the door was electrified. Somebody had pulled the main switch.

Actually we had been trying to send out a message. Jim had typed a short message saying the consulate is under attack, connected the tape in a loop, and put it on the teletype. It thus ran continuously, repeating the message. But Jim said had said he thought the people he had on the line when the attack started were transmitting themselves and thus could not receive our message. As far as I know, nobody ever got that message. All our equipment went down because they pulled the plug. We sat there for several hours, with them banging on the door, shooting at it, sometimes with a fairly heavy caliber, because it sure made an awful noise. They kept this up for several hours. We kept, in a low voice, trying to talk on the telephone, to reach somebody to tell them of our plight. The people we did reach later said they had tried to reach somebody, but no one could do anything. Everyone was staying indoors and out of trouble…. Time went by; it got dark. I said, “Well, let’s bite the bullet. Let’s do it.”

I told them to very carefully pull the safes away from the door and to unlock it. I opened it a bit, slowly and cautiously, and peered out. I could see nothing. It was dark and there wasn’t anybody around. I opened it all the way, walked into the room. I could feel the floor was covered with bullets that they fired at the door and into the building. I told Jim to go outside and turn on the juice, the electric power. Very little happened because they had shut it off during the day so there weren’t any lights on. We turned on lights. We saw that they hadn’t really made a mess of the consulate. There were mainly a lot of spent bullets and cartridges on the floor — I still have a small collection of them — a lot of glass, broken glass. We could see the bottles of wine that they had left. There was nothing else disturbed….

There was no question of escape

In the afternoon a couple of guys came to the consulate. For the first time we heard the word “simba,” the Swahili word for lion. They called themselves Simbas…. They took a couple of our vehicles. Every time they’d come in they’d yell “Simba” three or four times. So we had seared into our brains the word “simba.” That is a word I still have trouble hearing. I haven’t seen the movie “The Lion King” where the word is used often…. It was pretty peaceful in the early part of the night, but then suddenly the city was being bombarded. We couldn’t figure out for a time what it was. Then, we figured out that there must be some elements of the ANC across the river, on the left bank, and were lobbying mortars indiscriminately into the city….

Stanleyville, being where it is, is the heart of darkness. It is all the way up-river, it is in the middle of the biggest rain forest in Africa. It is literally in the midst of almost a thousand miles in every direction before you get anywhere. So where would we have gone? There is no place to go. In Bukavu they are on the lake, Kivu, and they had a boat. So at the last minute they could slip down the embankment to the boat and they’d be in Rwanda in five minutes. But we had nowhere to go. There was no question of escape…. [A] band of four or five Simbas dashed into the driveway in a jeep and started yelling and screaming at us. They started beating at us with their rifle butts…. I tried to tell the Simbas we were the American consulate, that we were not to be “disturbed,” that General Olenga had said the consuls were not to be bothered….

I was talking to them in French and, of course, they understood very little French. They said, “Okay, sit there.” They beat us a little bit. They said to wait there, and then drove off to Camp Ketele, leaving two behind to guard us.

They had rifles, they struck us a bit. Not viciously. I had seen ANC, other people, beat up people and they do it quite well. They’re quite adept at it, and I had seen the sorry results of these beatings. What they were doing to us was quite gentle compared to that….

[The consulate staff members were taken prisoner and held in the airport terminal, then moved to the Sabena Airlines guest cottages at the airport.]

On the 25th of September, we could see from our cottage that a Red Cross plane did land. From our cottage window we could see the terminal and the plane. We were elated with the prospect of seeing someone from outside our closed world. The occupants were driven away, presumably downtown. Nothing happened with us. I was beginning to get the feeling we would not meet the Red Cross officials. The next day, the 26th of September, two Simba officers came to us, handing us Red Cross forms…. We then saw the Red Cross people come back to the terminal. They got into the airplane. It taxied away and took off. This was one of the darkest days for us. Here we were, very hopeful that something might happen. We were utterly devastated. We knew we were there for the long term.

Q: How long, at this point, the 25th of September, had you been held?

HOYT: The attack on the consulate was on the 5th of August, six weeks….

“We found out they had been fed to the crocodiles”

Back in Stan, it was fairly quiet until about the 30th of October when the rebels decided to take all Belgians and Americans hostage. We found out when the Belgian consul, Nothomb, and the vice-consul, Duque, were brought to our cell. We found out that the previous day the order had gone out for all Belgians and all Americans to be taken hostage, a very large operation…. Up to now we had been the only hostages. They made it very clear that we, the Americans, were to be hostages and if the town was re-taken we would be used as shields….

Now, the whole Belgian and American population was put into the same status. As a matter of fact, in regard to our personal safety, this was a welcome development. I immediately saw that, before, their fury would be concentrated on us, the few of us. If the town was re-taken, either a bomb or whatever, we would be killed immediately. But now we had numbers. We had now at least…hundreds of people. There was now safety in numbers, I thought. I saw a group of fifty Belgians being marched into prison with us. I welcomed them into the fold. This, I knew, would improve our chances of survival greatly….

At one point, one night, we could see out in front of our cell from a little window high up on our cell, a sort of a silence fell on the prison as when something extraordinarily ominous was about to happen. We looked out and saw about 30 or 40 prisoners being hurried out the door. Silence. Something very serious was happening. These people had been kept in the “cachot,” the dungeon, the punishment cells, which are very cramped cells, for the last couple of months. They had been rounded up because their pictures had appeared on a poster for a political party which is known for backing the former prime minister, Adoula, one of the parties backing Belgians. The next day we found out that they had been taken out and thrown over Tshopo Falls and fed to the crocodiles down below. They wouldn’t have survived the fall, it was very high. So they were executing their prisoners. We knew that at one point the guards from Osio came into the prison yard to collect prisoners. The place had a very bad reputation. The guards had rhino whips. As they passed us, they said, “You’re next. You’re next.” People rarely returned from Osio.

We stayed in the prison over the next several weeks. We heard many rumors. We communicated with a bunch of what we imagined were trustees who were in a cell right opposite the little window. We talked a lot to them. They had a radio and would tell us what was being said. We found out that there was an election. That Johnson had been elected president against Goldwater. We knew there was a campaign but did not even know the candidates. That was one election I was forced to miss….

Q: How many days had you been jailed up to this moment?

HOYT: This go around was a month and 10 days….

On the 18th of November, two days later, a hush went over the prison. You could tell something was about to happen, as I had said when they brought out those 30, 40 prisoners and executed them, I remembered the same silence. The same when we were being held in the women’s toilet out at the airport and the crowd descended on the airport…. Everything all of a sudden went silent.

“They talked about which parts of our bodies they were going to cut off and eat”

And then we were aware of the noise of a very large crowd outside the prison…. A Simba rushed up to our cells and said he wanted the Americans. He said the Americans were to come out…. We were told to write our names on a sheet of paper. It was very ominous. It was the first time this formality had been required. Before this, it was always in prison, out of prison, no formalities. Outside the prison there was a legless midget pushing himself around on a little cart. He yelled and screamed what I guessed were obscenities, at least by the tone not very nice things. We were loaded into a jeep — six of us in a jeep and the two others in a Volkswagen. We weren’t told anything but we knew this must be it.

In my heart I somehow felt that it wasn’t, likely, but not necessarily. I tried to tell an obviously nervous Carlson and the others to calm down. “We’ve been through this many times, maybe again we will survive.” The jeep pulls up to the Lumumba Monument, where there is an enormous crowd filling the entire square. The other two guys in the Volkswagen were put in with us. We were piled in the back of the jeep. The crowd gathered outside. Those close by started poking at us. Through gestures and yelling at us they were describing what was going to happen to us. It wasn’t very pleasant. They talked about which parts of our bodies they were going to cut off and eat. Some pointed to their genitals. We knew, very likely, what was to come. They managed to get through the curtains of the jeep and jab at us….

We were headed for the Presidential Palace, the driver told me. “You have General Olenga to  thank for saving you,” he said. At the palace, there was another big crowd filling the vast lawn. We were unloaded from the jeep, lined up….It looked like a Portuguese or Greek, photographer. He’s snapping pictures. We lined up and we get our pictures taken. These pictures later appear in Life Magazine….

thank for saving you,” he said. At the palace, there was another big crowd filling the vast lawn. We were unloaded from the jeep, lined up….It looked like a Portuguese or Greek, photographer. He’s snapping pictures. We lined up and we get our pictures taken. These pictures later appear in Life Magazine….

Gbenye is giving a speech to the crowd. He says that we were supposed to have been executed that day. He spoke some in Lingala, some in French, so I could understand only part. But he said that Kenyatta of Kenya had appealed for our lives, so he was going to spare our lives until the next Monday. This was Wednesday.… We got back into the jeep to go back to the prison….

[On the 24th of November] at 6:00 we awakened to the sound of airplanes flying overhead. We know this poses an immediate danger to the hostages. We all get up, get dressed, and have a quick breakfast of beer and sausages–a typical Belgian working man’s breakfast. We don’t know anything of what was happening. We telephone around town. All we hear is that airplanes are flying around. Somebody says they saw paratroopers….

[On the 24th of November] at 6:00 we awakened to the sound of airplanes flying overhead. We know this poses an immediate danger to the hostages. We all get up, get dressed, and have a quick breakfast of beer and sausages–a typical Belgian working man’s breakfast. We don’t know anything of what was happening. We telephone around town. All we hear is that airplanes are flying around. Somebody says they saw paratroopers….

We were told to start marching down the street. Alongside the column was this security type who had driven us to the Lumumba Monument. He told me, “We were trying to work with you. And, now–this.” What “this” was I don’t know, but I sensed I was targeted for whatever was about to happen.

We started walking down the street. A pickup with a machine gun mounted on the bed drove up, loaded with Simbas. A deaf-mute Simba, whom I had noticed before, and those with him began to argue with Opepe. It was obvious to us that they wanted to shoot us, right then and there. But Opepe was able to persuade the group in the pickup to leave. We marched down the street a little bit further and when we turned the corner another argument took place with some other group of Simbas. I heard something like, “But they’re already here.”

It was apparent that Opepe’s orders were to take us to the airport and use us as shields against whoever was attacking. With that, we were to sit down while they decided what to do. We had been seated for a few moments when I heard gunfire and saw chips fall off the corner of a building above us. I looked over and one of the young Simbas with a rifle still at his waist started shooting at us, shooting into the crowd.

Before I could move, Grinwis shouts, “Let’s go, Michael!” So we started running, going down a gravel alley. I fell down, picked up and ran some more. David also fell down. I looked around, and David was gone. I ducked behind a little wall and waited a few minutes. I heard the sounds of firing and yelling. I looked to the side. My rear was exposed to the whole street there. Anybody walking down that street would have seen me.

Before I could move, Grinwis shouts, “Let’s go, Michael!” So we started running, going down a gravel alley. I fell down, picked up and ran some more. David also fell down. I looked around, and David was gone. I ducked behind a little wall and waited a few minutes. I heard the sounds of firing and yelling. I looked to the side. My rear was exposed to the whole street there. Anybody walking down that street would have seen me.

I waited about 15 minutes and then I saw a couple, looked like an Asian couple, come out on a balcony above me, looking down on the street. I think they’re not African people exposed there. There must be something friendly there. So I got up, and then I saw a soldier across a field. Without my glasses I couldn’t make out what he was. I raised my hands and he motioned me on, still his rifle pointed at me. I climbed over a fence, crossed a field and came to him. By that time I could see his beret and assumed he was Belgian. I said, “I’m the American consul; take me to your leader.”

“There had been a massacre of our group in the street”

A Belgian paratrooper who took me to his commander, looking at a map on his jeep. I realized that we were safe.

My immediate concern at that point was the American missionaries who were out on the outskirts of town. I said, “Look we’ve got some missionaries out there. Give me some troops and let’s go find them and bring them in.” The colonel said his orders were to stay right where they were, to secure the city. They weren’t going to move, to go out of town or anyplace else.

One of the little three-wheeled jeeps drives up. I could see that it was Clingerman, my predecessor as consul there, in fatigues, and a pistol strapped on his side. He didn’t recognize me at first, then he did and we embraced. I again explained to him that we had to go out to Kilometer 8 and get those missionaries. He said, “Look, we’ve just spent four million dollars getting you out of here. You go out to the airport, get on the airplane and get out of here.” Which we did, David and I….

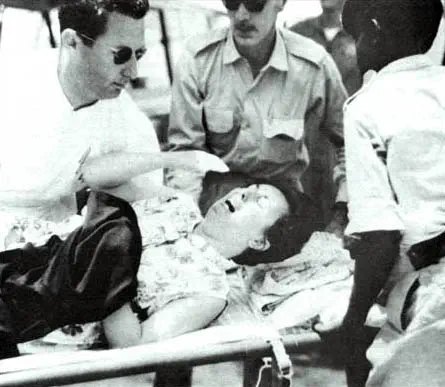

David and I started on the road to the airport per instructions. There had been a massacre of our group in the street. There were probably 20 killed and another 40 wounded. A number of them died on the way to Leopoldville. I saw one woman with her baby in the street. Someone led her away. We went out to the airport. There was still firing heard around. Not all the Simbas had fled.

David and I started on the road to the airport per instructions. There had been a massacre of our group in the street. There were probably 20 killed and another 40 wounded. A number of them died on the way to Leopoldville. I saw one woman with her baby in the street. Someone led her away. We went out to the airport. There was still firing heard around. Not all the Simbas had fled.

The enormity of it began to sink in to both David and me. This was a massacre of innocent people. Somebody told us that Carlson had been killed. He’d been the last to go over a wall and had been shot dead. Terribly sad not to survive the final moment.

When we got out to the airport, we went to the same baggage room where we had been before, in front of the women’s toilet. We had to keep our heads down because bullets were still firing over us…. David and I were led to the second airplane out. We climbed up to flight deck and sat on a bench behind the flight crew.

These were C-130s. The most beautiful plane in the world. Here we were, transformed. An hour earlier we had been in mortal danger, had been in prison, and now were here in this most modern marvelous equipment, flying back to Leopoldville.

It took some days before they cleared the Simbas from the runway and from the city. In fact, it took the mercenaries and the Congolese army a full year to get the remnants of a few hundred Simbas confined to a small area in the Fizi Baraka hills on the edge o f Lake Tanganyika. It was during part of this year that Che Guevara went to the Congo to work with the Simbas.

Q: Was there any cannibalism?

HOYT: There certainly was some ceremonial cannibalism. But these were undisciplined troops. The paradrop had been finally decided on because we were being held hostage. Gbenye had made public pronouncements over the radio that all the hostages would be killed if the city were attacked….

Over the next year, the Simbas would slaughter the white missionary hostages whenever they were threatened to be overrun. Very few of the hostages survived, English, Belgians, Americans. It wasn’t just because of the paradrop. Before the paradrop, the Simbas said they would kill everybody if they were attacked. There was an international furor over the paradrop, led by the Soviets and radical Africans….

Once in the air, we were told that the other three staff guys had survived the massacre and had gotten out on the first plane. Ernie had just stayed right in the middle of the street until the paras arrived. Mac Godley was overjoyed to see me. He took me to his residence, and before I knew it, there I was, still in my shirt with blood on it from the dead child, at the white linen dining table with the cream of the Belgian business community. I was, of course, the center of attention. The only thing I could say was that the devastation by the Simbas would make the task of the restoration of the Stanleyville economy a tremendous task. In fact, if you read Naipaul’s “A Bend in the River,” it never recovered anything of its former status. In fact, the Congo never really recovered….

Q: Were there U.S. paratroopers and Belgian paratroopers?

HOYT: Belgian paratroopers flown in American C-130s. The only Americans involved were the  flight crews and the aircraft guards. Of course, the former consul, Clingerman, also went in with the planes. The refueling took place at Ascension Island and the final jump-off was from Kamina, a big Belgian air base in the southern Congo. The final “go” wasn’t given until early that morning. It was almost an inevitable “go,” because everything was set and, primarily, because the rebels had broadcast over the radio, and published in the papers, the very terrible things about what they would do to the Europeans if Stan were taken, like making lampshades out of their skins. The land column, which eventually arrived just before noon, was certain to have taken the town, even without the paradrop, but it was thought they could not do it fast enough.…

flight crews and the aircraft guards. Of course, the former consul, Clingerman, also went in with the planes. The refueling took place at Ascension Island and the final jump-off was from Kamina, a big Belgian air base in the southern Congo. The final “go” wasn’t given until early that morning. It was almost an inevitable “go,” because everything was set and, primarily, because the rebels had broadcast over the radio, and published in the papers, the very terrible things about what they would do to the Europeans if Stan were taken, like making lampshades out of their skins. The land column, which eventually arrived just before noon, was certain to have taken the town, even without the paradrop, but it was thought they could not do it fast enough.…

“One thing kept us going was the thought that if we got ours, you’d get it too.”

After the lunch at the ambassador’s residence, David and I had a press conference…. With the press, I tried to get through the character of the Simbas, making it clear that these were not the sort of people that should be sympathized with. Not only did they murdered whites, but they were very brutal to their own people. Of course, when Mobutu and his people flew into Stanleyville, there was a terrible massacre of all those suspected of being rebels or sympathetic to them.

That night after everything was quiet, and we had a few drinks, I finally had a chance to talk to [Ambassador] Mac Godley. “Well, you know Mac,” I said. “One thing kept us going was the thought that if we got ours, you’d get it too.” He didn’t say anything. I don’t even know whether he heard me or not. We had had more than a few drinks. The DCM [Deputy Chief of Mission], Blake, tried to disappear in the sofa. I never had a chance to talk to Mack again.

Subsequently, he has told different stories. Sometimes he admitted he had ordered us to stay. At other times, he denied it. My wife remembers very well, that when she was still at the embassy after being evacuated, she met somebody in the hall who said, “Jo, isn’t Michael so brave for staying.” Mac said, “No, I ordered him to stay.” Jo said, “Well, I’ll remember that and I have witnesses.”