The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a landmark international climate treaty which entered into force in March 1994, provided the basis for future agreements, including the one reached in Paris in December 2015.

Robert Reinstein, the United States’ top negotiator at the United Nations, and Stephanie Kinney, one of the State Department representatives, recount the considerable obstacles the U.S. faced in reaching an agreement, including demands by developing countries for an upfront guarantee of money and technology and how they were able to finesse this with well-crafted language — after a high-stakes poker match. They note how then-Senator Al Gore followed the U.S. delegation everywhere and was often critical of its bargaining positions, in part because the U.S. kept to its position of “no on targets, no on money and we’re going to come back to you on technology.”

Read Parts I and III here. Read more on the Montreal Protocol. Go here for other Moments dealing with negotiations.

“The U.S. was being hung out to dry”

KINNEY: In January of 1990, President Bush comes to the meeting of the IPCC and essentially identifies himself and his administration with an intention to respond to the findings of the IPCC.

Fast forward to June, and because we had nothing else to offer, he announces at a meeting in Malta that the United States will host the first session of the UN negotiations on a climate treaty. No one at the State Department had been consulted on this. We wake up and say, “Oh, my God! Did you hear what just happened? The President announced that the United States is going to host the first negotiating session of the Framework Convention on Climate Change!”

That was in June of ’90. In September of ’90, we still had no money and no venue. We actually did serve as host, and the President attended and spoke to the opening session of the negotiations, which was held at Chantilly, Virginia, in February of 1991. Once again, the thermometer topped 70 degrees, a brilliant Washington “January thaw” in February.…

REINSTEIN: In Chantilly, there was a crisis. We were establishing the organization and structure of the negotiations, along with the terms of reference for the negotiating groups for the convention….There were Working Group I and Working Group II, Negotiating Group I and Negotiating Group II. The Europeans wanted two groups, one on carbon dioxide and one on the other gases. I said no, and we basically stiffed them on that, and we got commitments and mechanisms as the two groups. All of the really tough stuff went into commitments. That’s the one I watched.…

The big crisis was on money and technology. That’s the standard developing country agenda. The Group of 77 of the 130 or more developing countries had agreed they would go for the jugular in Chantilly, and they picked the Indian chief negotiator [Chandrashekhar Dasgupta] as their spokesperson. He was an old UN hand, old 1970s New International Economic Order….Very, very bright. He wanted in the terms of reference of the Working Group on Commitments an up-front guarantee of money and technology.

KINNEY: An example of the importance that other countries attached to the UN is that they do send only their best and these individuals become skilled and adept and rely on both history and experience. They have an opportunistic approach so that if, for example, you don’t get what you wanted in UNCTAD [UN Conference on Trade and Development] in the ‘70s, you keep trying for it whenever and wherever you can, and climate was just another opportunity to return and get what you had been denied earlier.

REINSTEIN: He very articulately laid out, “We need to have this. It’s a matter of principle. We have to have the money and technology without which we can’t even play in the game,” and so on. All of the others of course put their signs up and, “Yes, yes, yes.”

I said, “I’m sorry. These are indeed topics on the agenda. We will need to address them in the context of the negotiations. We agree that they are on the table. How they will be resolved cannot be agreed up front because they must be a part of the whole package. Everything in the convention. The answer to the question will not be known until we come to the end of these negotiations, and cannot be put in the terms of reference. We do not accept that.”

The British put up their sign to speak. They were indicating, “Yeah! Yeah!” and were going to say we strongly agree. The Dutch, however, were in the EC presidency (they were then 12 members), and they came back and actually put the British sign down and said, “We will speak for the Community as President for these six months.” They just said, “Well, this is a problem between the U.S. apparently and the Group of 77. We’ll just have to see.” In other words they did not support the U.S. position.

Then the Canadians and Australians made similar interventions. We, the U.S., were being hung out to dry because we were the only OECD country that had not agreed to a CO2 stabilization target. This was their message back: “You want to play that way? You can take on the G-77 alone.”

“By body language and intonation, I communicated the fact that I had the authority at any time to walk out”

KINNEY: The EC and others could posture. They could play the good guy to the hilt because they knew they would never have to fulfill what they were seeming to advocate because the United States would take the negative and never agree.…

REINSTEIN: Those votes in the General Assembly — back then there were fewer countries– like 144 to 1 with the U.S. being the 1, were pretty common. We’re tough. We don’t cringe. We’re not embarrassed because we’re the only one willing to tell the truth.

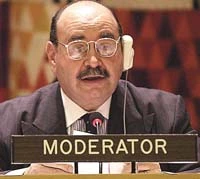

On the next to the last day, the meeting broke up at 2:30 in the morning unresolved. We went outside the meeting room. The meeting was being chaired by Ambassador Raul Estrada from Argentina (pictured), who was the Vice Chair of the Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee (INC). The INC was the body which was established by the UN General Assembly resolution to negotiate the framework convention.

Estrada and I and Dasgupta went out in the hallway. This was in Chantilly. Estrada said, “We have a problem here. Are we going to resolve this?”

I said, “Well, we have to resolve it, I agree, but it has to be resolved in a way that is acceptable.” By body language and intonation, I communicated the fact that I had the authority from the White House at any time to walk out and take the member U.S. delegation with me even though we were hosting the meeting.

I never said it. I never threatened anything. I communicated it by body language, and I looked at Dasgupta, and I could see he was listening. He was nodding. His eyes were blinking very frequently, and I knew he was going to compromise. I could read it. That was at 2:30, 3:00 in the morning.

“I didn’t know how good poker players they were”

About 6:30 the phone rang. I was staying there at the center in Chantilly, and it was Allen Bromley, the Chief Science Advisor for the White House, who was chairing the sort of cabinet-level group and reporting to [White House Chief of Staff John] Sununu. He said, “What happened yesterday?”

I said, “Well, we got a little problem,” and I explained it.

He said, “What are you going to do?” I said, “We’re going to finesse it. We’ll be okay.” I didn’t tell him how. He said, “Okay.” He informed Sununu, “There’s a problem, but Bob will take care of it. No problem.”

Then about 7:30 or something the Chair of the negotiations called me to his suite and said, “How are we going to resolve this problem?”

I said, “We’ll have to work around it.”

He said, “Have you got any thoughts on language that might do it?” I made a few notes I thought might work, and then I went out. He called Dasgupta in and met with him. Then he called us both like two school boys. He said, “I listened to both of you and thought about it, and I have some language that I think might resolve the issue,” and he put a text in front of us that reflected my thoughts expressed to him earlier.

But I did not tell my own negotiating team, the U.S. delegation, that I had total authority to fix the problem. Not because I didn’t trust them but because I didn’t know how good poker players they were. You know, you can go out and you’re having coffee, and you kind of smile a little bit inadvertently, and you reveal that there’s something going on, how we have might have fixed this.

I trusted them absolutely on anything they said, but I didn’t know how well they could control their body language such as not to reveal this, so I didn’t tell them.

After this meeting having the compromise text shown to both of us, I said, “Well, I know how the White House is very concerned about these things.” We took 20 minutes, so my people said, “Well, are you going to call the White House?” I said, “I’m going to get a cup of coffee first.” Then I disappeared, went to the bathroom and stuff, and killed 20 minutes and came back and said, “Okay, the language went through.”

It was an example of — I don’t know what you call it, kabuki?—where it had to appear there was this great crisis and that the Chairman of negotiations had intervened to get a compromise, whereas in fact it was in the end arranged by the United States very quietly….

“Al Gore was feeding the European Environment Ministers the script to use against the United States”

Q: Did you have anybody breathing down your neck from Congress?

REINSTEIN: [laughter] Al Gore? [Senator from Tennessee] John Dingell? [laughter] [Representative from Michigan, Chairman of the House Energy Committee]

KINNEY: They traveled with us!

REINSTEIN: Al was so obsessed he would follow me around the world! He’d be in Geneva outside of where we were meeting, holding a press conference in the street condemning me. I invited him to a couple of our delegation meetings, and he came into one negotiating session in Geneva.

There were two seats at the front table, and I let him sit next to me at the table next to the microphone. I said, “Do you want to say anything?” consistent of course with our instructions because we’re not allowed to say anything that’s inconsistent with our instructions. He was a Senator. Al and I got on a first-name basis.…

I will not say too much about Al on the record. I will give only one anecdote. I had a meeting with the Italian Minister of the Environment in Milan in a quiet little room about this size off of the lobby of the hotel. He and about three other people were on the other side of the table, and about two or three of us on our side, and I saw he was reading from a piece of paper. He spoke English pretty well.

I saw that it was a fax. A fax has a signature on the top and bottom of each page. What it said at the top of the page I could read upside down— my eyes were better then — was “From the Office of Senator Al Gore.” Al was feeding the European Environment Ministers the script to use against the United States. I suspect it was unconstitutional. There is some prohibition about the Congress engaging actively in foreign policy as opposed to overseeing from Washington.

“With enough beer, we managed to come up with a finesse on language on targets”

REINSTEIN: Back to Chantilly, the session ends with the establishment of the working groups and their terms of reference and certain language, for example, on money. The governments will seek for ways to “facilitate” looking at the money and “facilitate” technology transfer….

At the Second World Climate Conference in December 1990, prior to the beginning of climate negotiations, there was a worldwide meeting, on the environment and climate, and such noted “meteorologists” attended as Margaret Thatcher, King Hussein from Jordan, people like that. All of the “weather” people….

The negotiations on difficult issues were over the weekend prior to the Monday when the conference began. The target question was finessed on Friday night after a reception in Geneva. Four of us went out to dinner and ate some steak and drank a lot of beer, with me for the U.S., Keiichi Yokobori for Japan, Pier Vellinga who was Dutch (and also an IPCC subgroup chair) for the Dutch EC presidency and Per Bakken from Norway, representing EFTA [European Free Trade Association], which was still a fully functioning separate organization..…

It was everybody but the EC-12. Anyway, the four of us, knowing each other personally and all friends, some from the Montreal Protocol days, with enough beer, managed to come up with a finesse on language on targets. We had to fight not to have it undone by some people who didn’t understand that there was a deal.

Then the question was how to deal with the developing countries on money. During the backroom negotiations, there was a working group on the money and technology chaired by Mexico, Victor Lichtinger (pictured). Victor and I were friends, and we had lunch together. He said, “How are we going to finesse this money and technology problem? You got any ideas?”

Again, I’m a language guy. I can often find ways to bridge differences through carefully chosen words. “Okay, let me try my hand,” so over lunch I wrote again some notes for that paragraph. He came back from our lunch as chair and said, “Based on consultations, I have some language that maybe we’ll see if we can agree on.”

He put a text reflecting my notes in front of the group. It said, “New and additional resources should be mobilized…” It did not say they should be “provided” or who (industrialized countries) should provide them, or what kind of resources. But it contained the key words sought by developing countries – “new and additional”—and this was the important signal to get the language accepted by the G-77.…

REINSTEIN: About the second session, which was in Geneva in June of ’91. It illustrates the importance of these personal relationships. I went around in April and May, and I met with friends. Basically all the key players were friends by that time, and I said, “It would be very helpful if an idea that was originally floated by the Japanese — known as ‘pledge and review’ — could find its way into the negotiating history here. This could help facilitate the U.S. finding a way to participate.”

The idea of pledge and review was essentially the best efforts the countries would commit to would illustrate what they intended to do if they could deliver. In our case, the fact that we have separation of powers of the branches of government, with Congress independently controlling legislation and passage of any new law that might be required by a treaty, forces the U.S. to essentially commit to best efforts to implement any agreement that it signs. If Congress fails to agree and provide implementing legislation, then the U.S. cannot ratify the treaty.

Negotiating Tactics: Pledge and Review and the Proverbial ‘Non-Paper’”

KINNEY: We are describing the process by which the Framework Convention on Climate Change was negotiated by the United Nations Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), a process that began in February of 1991. The INC was set up by the UN General Assembly in the end of 1990 as the forum for negotiating a framework convention on climate change, which was to be signed in Rio de Janeiro at the Earth Summit in June of 1992. Backing up a month from the date for Rio, we had basically 15 months in which to reach an agreement.

I think it’s very important to underscore that Rio and the framework negotiations were on two totally separate tracks. They only came together for the official signing at the Rio conference. People very often confuse the two.

REINSTEIN: Yes. They don’t understand that the text of the convention was adopted in New York in early May and was merely opened for signature by the respective heads of state or equivalent at Rio. The Convention had already been adopted by all governments.

In other words, there was nothing more to negotiate, which is why the two of us and some others didn’t even go to Rio. Some said we probably shouldn’t be seen in Rio by people that want to reopen the climate treaty language.…

I’ll give you a little more details just in passing to give you a flavor of the game and the way it works. I had planted or gotten both Japan and the EC — still the European Community — to introduce the idea of pledge and review; that is, countries propose what they are willing to commit to and willing to have the rest of the world come and ask them questions and things about what they had done through their best efforts as opposed to legally-binding, top-down targets….

Both Japan and the Europeans introduced it in the June negotiating meeting in Geneva, and it just went into the record which is all I wanted….

Q: Why did you just want it in the record?

REINSTEIN: Because at the end I wanted to pull it out, and I wanted to have a negotiating history. In other words, my end game is I wasn’t sure how much I was going to be able to get people to agree to, how much I was going to have to create it myself or ram it through, and we’ll come to that today. I needed to have some key concepts and approaches in the history so they were not totally out of the blue in the end game.

KINNEY: With so many actors, and so many egos, one could not just pick an idea out of the blue and ram it through, especially if one were the United States. Having certain language in the negotiating record or minutes of the meetings gave that language legitimacy beyond the one or more countries who may have been involved in introducing it. Once part of the record, the concept or language or formulation could more easily be accepted because it had in fact been introduced earlier and at least minimally discussed by all.

REINSTEIN: Yes. Introduced and rejected, But the alternative wasn’t flying either, so you could come back and say, “Well, if that isn’t going to work, then what is?” What has been here on the table and could be looked at again?

In other words I had already in the spring of ’91 pretty much the whole game plan in my head. I had never written it down until very close to the end, for Bob Zoellick, the [State Department] Under Secretary who was acting for [Secretary of State James] Baker. Baker had recused himself, so Bob Zoellick was the acting Secretary-level person.

He said, “I want you to write down your end game plan.” I said, “I don’t want to write it down.” He said, “You’ve got to write it down. You’re out of the country 50% of the time. If I get called to the White House, I need to know where you’re trying to go in order to protect your interests.” So I did write it down in the end, only for him on plain white paper from Bob R. to Bob Z. Plain white paper, no clearances, not through anybody, but classified secret.…

KINNEY: The proverbial “non-paper,” which is a tradecraft term of art used to refer to a text on paper with no identifying marks, a paper the authorship of which is claimed by no one and therefore a paper of no official standing or accountability. Non-papers are most often used to test language or ideas for feasibility or to convey information one is not supposed to be conveying officially.

REINSTEIN: Anyway, that was the only time I wrote it down, and that was maybe six weeks before the end, eight weeks before the end. It was a plan, and it was a staging.

“The U.S. position: No on targets, no on money”

What I’m going to do is try and walk through how both the negotiating process itself but all the related parallel domestic and international tracks were also being tuned to line up in this direction. Or at least we were protecting ourselves from problem things being introduced in ministerial declarations here and there or in the UN system or UNCED [United Nations Conference on Environment and Development] or OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development].

I had to do a lot of running to places to basically just bracket ministerial declaration drafts and say, “The United States can’t sign them today.”…

The whole world was against us and for various reasons. The developing countries wanted the money and technology for free, and the Europeans wanted the binding targets because they had already decided that they were no longer competitive in energy-intensive industries, and were going to be de-industrializing. Also they were jealous of us because we were energy rich and they were energy poor, and they wanted to hobble us in the same way.

KINNEY: Western European countries knew that, as a region, they would eventually have the advantage of Eastern Europe coming into the play, which was important because Eastern Europe’s industrial base was very underdeveloped and less energy intensive compared to that of France and Germany, for example….

REINSTEIN: Basically I had to beat the EC/EU on the targets, and I had to finesse the developing countries on money and technology. I met already with Sununu who asked me what my general approach was going to be on targets, money, and technology. I told him no on targets, no on money. The Constitution didn’t have the authority anyway in the Executive branch.

Technology was an area where we could actually use our leverage as being the major source of innovation and technology in the world to gain a presence in the developing markets outside of the OECD countries, so that was the plan on technology.

Anyhow, that was broadly the U.S. position: no on targets, no on money, and we’re going to come back to you on technology.