Throughout the 1970s, trouble was brewing in Chad. President François (N’Garta) Tombalbaye was the first president of Chad following its independence from France in 1960. His authoritarian regime became increasingly distrustful of and alienated from Chad’s military and Tombalbaye had jailed several prominent commanders. An insurgency in the north led by the Libyan-armed FROLINAT [National Liberation Front of Chad] guerilla group underlined the frustrations of the northern population with the regime. At the same time, a drought had set in and wheat crops were failing, beginning a long famine across many Saharan countries and increasing the political unrest.

All this led to a coup d’état on April 13, 1975 that violently deposed Tombalbaye. General Felix Malloum seized control of the state and took over as head of a seven-member junta. The coup left many issues unaddressed and their lack of resolution led to more conflict. Years of power struggles ensued.One of those who witnessed the coup was Richard A. Dwyer, Deputy Chief of Mission in N’Djamena from 1974-1977. Charles Stuart Kennedy interviewed him in July, 1990.

Please follow the links to learn more about Africa, coups d’état, the perils of being PNG’d, or another moment in Richard Dwyer’s storied career.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

RICHARD A. DWYER Deputy Chief of Mission (1974-1977)

“Why didn’t the United States take over this country?”

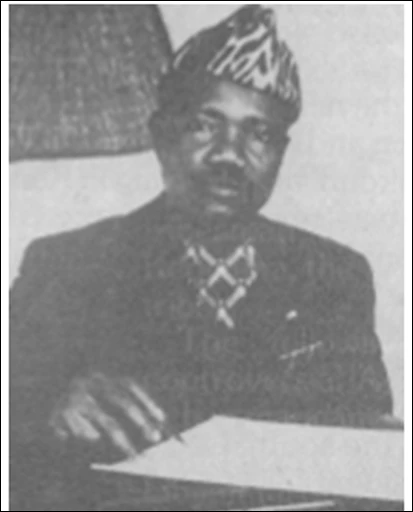

The President of Chad, Tombalbaye (seen left), was one of the last, if not the last, remaining civilian presidents of those West African countries that had become independent in 1960. All the other countries had had their military coups d’état and the military or somebody else had taken over.

Tombalbaye had managed to survive principally by splitting up the opposition into several groups. For example, we not only had a Chadian army, we had a frontier force, or militia, a gendarmerie and a presidential guard, each of which was a counter balance to the others.

Secondly we had the French army. Chad sits in the middle of the African continent and had the largest airport in the area. It is the airport where most north/south African traffic stops. So we had one or two regiments of the Foreign Legion there and at least one other regiment, and we had an on-going civil war that went in fits and spurts and had been since shortly after independence.

In effect in these countries… there is not a true government, in the sense that there is in the western countries. The villages were neither oppressed nor very much helped, so you are talking about the government establishment as a couple of big towns.

But Tombalbaye became, or was when I got there, an alcoholic — but half the government was and so was half the next government — but he became increasingly incapable of governing the country. He became increasingly paranoid. He was out in this isolated place waiting for them to come, and the more isolated he became, the less effectively he could even attempt to govern the country.

He suggested to the ambassador before I got there: why didn’t the United States take over this country, just call him president and the United States could do whatever we want. The telegram was called, “Chad on a Silver Platter,” which we didn’t want.

Chad, like Sudan, is one of the African countries that is Arab in the north and black in the south. The belt that became famous because of the drought in those years, the Sahel, basically is that belt that goes across Africa where, to go north, the crops need irrigation, and to go south they do not. Of course it was the movement of that drought belt south that brought the horrendous famine as it has done before.

The black population became the governing population upon independence, offsetting centuries of de facto if not actual Arab rule. The Arabs of the north had always considered the blacks as inferior citizens from the time of slavery — and I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if there were still some black slaves somewhere up near the Libyan/Chadian border.

Although the French alleged in 1923 that the country was pacified, it never really was. From the Mediterranean straight south to Chad are traditional caravan routes that are still used by trucks and land rovers, which go right through civil wars and everything else, so you would find in the bazaars of the capital, N’Djamena, dates from the north and carpets from Turkey, etc. at most times during the civil war.

Tombalbaye had appointed black governors to the north region, and from a time when the Arabs could consider themselves first rate citizens, they in some respects became second class. This area of northern Chad had never been pacified. You went up there at your own risk.

As a matter of fact, when we arrived in Chad there was the Claustre affair. Madame [Francoise] Claustre (seen right) was a French archeologist. She and a couple of West Germans were being held hostage by Hissènne Habre and the rebels in the north. The German government simply flew an airplane in and brought their countrymen back. Of course, the Chadians immediately broke relations with Germany which the Germans didn’t particularly care.

But this the French couldn’t do because this was their client state. In effect the French were paying for the government of Chad. The only money crop to speak of was cotton, through which most of their foreign exchange came from, but most of it was subsidized by the French government.

At the same time we had Conoco, an American oil company, looking for petroleum, which they actually found up in the desert and in several places, and this had the prospect of making the Chadians possibly independent in terms of foreign exchange at least. The American government had very little interest other than the fact that it was an American company.

There was a small AID [U.S. Agency for International Development] program there. We were putting in about $10-15 million a year. The program really wasn’t formally established until after I got there. We also had 50 or 60 Peace Corps volunteers–an excellent program. Superb young people, and some not so young.

I still rankle when I think of these kids out in the boonies where there was no way we could get them back if they got sick and really wanted to come back. When Nixon commented about the Peace Corps being a draft dodger’s paradise or something, I often wished he could have seen these kids up there, because I thought the world of them.

“Maybe I should just say nothing, but that is not what I am paid to do out here”

…[T]he overthrow of Tombalbaye was a military coup d’état despite the fact that he had gotten the forces divided. He was overthrown and I will never forget it because I had sat there on a Friday in this modest little country. However, the situation was tense.

I talked to our military attaché and our station people and our political people–is this guy going to last or not? We weighed the pros and cons–he had just jailed the top militia, gendarmerie officers and top army officers. I sat down and said, “You know, maybe I should just say nothing, but that is not what I am paid to do out here.” Maybe there is somebody who is interested back there.

I wrote a long analytical piece that said that in effect I think he is good for another three to six months. I gave it to the communications clerk, and of course we were still dependent on telex there; we didn’t have radio communications. Went home.

About 3 o’clock Saturday morning the firing begins and I said to my wife, “God damn it to hell.” My house was between the army camp and the President’s lot. I went out and stood on the road and the troops were going by, and the shooting, etc. Boy, was I ticked off.

There was a French intelligence colonel across the street from me. He walked over and I said, “Are you doing this?”

He said, “If we are, I don’t know about it.”

I think the answer was that he may have known about it but he wasn’t doing it. At about that time the commanding general of the Chadian Army pulls up and he says, ignoring me, to this French intelligence colonel, “Which way do I jump?”

The colonel says, “I don’t know, but jump one way or another.” So fortunately, the general jumped the right way. Tombalbaye was overthrown, he was killed in his bungalow and his body was taken up in one of the old Chadian Air Force DC-3’s and jettisoned somewhere out over the desert so that it could not be a form of pilgrimage.

“There was no way I was going to let these people stay there”

As the civil war began to heat up a little bit and the rebels began advancing towards the south, I became concerned about two Peace Corps volunteers we had up in Faya Largeau, which was up in the central part of the country–in the Arab part, original Beau Geste country.

The military in their wisdom had decided to give our DC-3 to the Ethiopians, before the Ethiopian revolution, of course, and had promised to replace it with a Lockheed King Air. But the Lockheed mechanic took one look at the country and said no way he was going to be there and the Air Force wasn’t going to assign an airplane without a mechanic there, so we lost our airplane, which meant that I lost the ability to get these people, which I could only do in the dry season anyway.

When it became time, I thought, to get them out — the French had withdrawn their teachers, it looked like the government was going to lose at any time the rebels made a push — I sent them word through the Foreign Ministry that they were going to come out.

About one o’clock that morning the Foreign Minister called me up and said, “Mr. Dwyer, I am speaking on direct orders of President Tombalbaye.”

I could hear the music blasting in the background and the glasses clinking and it was obviously a great party. He said, “I am formally instructed to inform you that if you pull those two Peace Corps volunteers out of Faya Largeau, the President will expel the whole Peace Corps and maybe your aide with it.”

I said to the Foreign Minister, “Fine. We will talk about it in the morning. I will see you tomorrow and let you know then.”

There was no way I was going to let these people stay there. I didn’t even bother to ask Washington. That would have just held things up for days. I went down the next morning and I said to the Foreign Minister, “Mr. Foreign Minister, thank you for your call. I have informed Washington that it is the decision of the Chadian government that they would be very unhappy were we to withdraw our Peace Corps volunteers from Faya Largeau…”

The Foreign Minister said, “Well that wasn’t what the President told me last night.”

I said, “My French isn’t quite up to snuff Mr. Foreign Minister, I guess I misunderstood you.”

He said, “Well, maybe you didn’t.”

But then we wondered how we would get them out. They are a couple of hundred of miles up in the desert. Fortunately, that year was the Soviet’s year to deliver drought aid up there and the Soviets had a couple of Soviet transports. By coincidence, the Soviet Ambassador was a great friend and he, unfortunately, had the habit of giving me a great big kiss every time he saw me — he had been the economic counselor of the Soviet Embassy in Sofia. He was terribly bored in Chad — he had almost nothing to do. He was a pretty nice guy.

I said, “Vladimir, old buddy, would you go and shanghai my Peace Corps volunteers and bring them back?”

He said, “Certainly, would be happy to do so.” And he did so.

The next flight to Faya Largeau, the Soviets picked up the Peace Corps volunteer — fortunately one was in town so there was only one up there — and brought him back kicking and screaming.

He said, “They wouldn’t have hurt me, I have members of [rebel leader Hissène] Habré’s family in my English class. They wouldn’t have captured me.”

I said, “Listen, they have a whole bunch of people up north who said the same thing. I have been around these parts of the world long enough. You may think you are half Chadian, but you are not half Chadian to me and not half Chadian to the Chadians. I am delighted to talk to you and get a briefing on what is going on in Faya Largeau but I want you out of there and you are not going back.”

Whereupon the kid went out and wrote a letter back to someone in the United States that said that son of a bitch in the Embassy has been a real pain in the ass. He is just like all the other State Department people, but he will get around him because he knew Habre… Well, of course, what the kid doesn’t realize is that all his mail is being read.

I liked the Chadians, but I never quite forgave them. Ambassador [Edward Little]’s wife was not well and had been taken back to the United States. The Ambassador had decided that he had to follow. He left and I was again Chargé. He had just gone the week before when the kid wrote this particular letter including me and the public affairs officer, who had a high profile, too.

The Ambassador gets on the plane, having been decorated by the new military regime with the order of the Golden Camel, or something, and two days later the Foreign Minister calls me in and says, “Dick, this has nothing to do with you personally, but we are PNGing [declaring Persona Non Grata] your public affairs officer, your station chief and the brat who was in the Peace Corps.”

Of course I knew nothing about the letter. I had no idea what had happened. I called these three people into my office, individually, and said what did you do? Nobody could account for it. I knew the public affairs officer, a big fellow about 6 feet 3 inches who wore cowboy boots, adding another couple of inches, with a red beard, spoke good French and learning Arabic, knew everybody in town and in short, made the new government very nervous. In addition to which he had gotten into a fight with the Minister of Education, because the Minister of Education’s wife, who had been a long time employee of the USIA library, was grilled by the police after there had been a theft.

So I could understand why they would get rid of him. They were getting rid of the station chief because he was declared (and by declared I mean he was identified to the government of Chad) as an employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, and was there with their permission and consent.

But we had had the coup d’état and the government change and it looked like a good time to get rid of him. And the Peace Corps volunteer, I didn’t know what happened to him, although I could guess. After a while I finally got a copy of the letter. The only thing that was confusing about it was that the Peace Corps volunteer identified me as the CIA chief.

“The whole cabinet jumped out of an airplane”

Basically what happened to the new government is that it lost the war. The government was composed of military officers. Felix Malloum, who had been in jail and had been a general, became the president. The Foreign Minister had been a Lieutenant Colonel in the Guard, but all of them had been in the French Army at one point or another. Most had served in Algeria and a few in Vietnam.

They were basically military men who simply could tolerate this highly corrupt and incompetent government no longer, as is often the case, only to find running the government is much more difficult than anyone had imagined. For the most part they were decent people.

I will never forget the Independence Days, which I lived in dread of after the military took over. I had heard rumors about the first one to the effect that the whole cabinet was going to jump out of an airplane and land in the stadium for the Independence Day parade. I laughed at it, but when Independence Day came, the whole cabinet jumped out of this airplane and did a pretty good job of it too. They were all paratroopers.

On the second Independence Day — by then things were getting to be a little dicey. My daughter was home from school, from prep school abroad, and so she and my wife had decided to take advantage of the long weekend and take a look at the animals in the game part in the Cameroon. I was, therefore, a bachelor there.

“What is the French word for mattress?”

The next ambassador, Bill Bradford, came as a fresh breeze. He was an old Africa hand and he asked if I would stay on another year. I said “with the greatest of pleasure.” Except for the horrible diplomatic incident I involved his wife in when he first got there, we got along wonderfully well….

The French Ambassador had our new Ambassador and the whole Embassy over for dinner shortly after their arrival. Our Ambassador decided to reciprocate and we had the whole French Embassy staff over for a lovely dinner. Jody Bradford [the ambassador’s wife], who was an effervescent, attractive, active, good looking blond woman, who was great fun, had at the time pretty rusty French, but this didn’t stop her from using it.

Here we were having drinks before dinner and the French Ambassador’s wife and Mrs. Bradford were talking. Jody grabbed me by the arm as I was going by and said, “Dick, what is the French word for mattress?”

Thinking quickly I said “matelot” and went on my way.

The French Ambassador’s wife had said, “How are you getting on in Chad?” And Jody had said they loved it. The only problem is, she said that ‘We have the most uncomfortable bed in the world, and we have finally gotten a new mattress for it and it is nice and firm and has made all the difference in the world.’

Now I had just told the Ambassador’s wife that the French word for mattress was “matelot” which happened to be sailor and not “matelas,” which was mattress. A series of giggles came out of the circle surrounding my Ambassador’s wife. Unfortunately, she couldn’t figure out what was so funny, but the new firm “matelot” made all the difference to her happiness in Chad. Fortunately she had a wonderful sense of humor.

“I saw the guy throw what I thought was a rock at the President that turned out to be a fragmentation grenade”

[In 1977] things were getting dicey again and my wife was saying, “When I lose count of the coup d’états it is time to go home.”

She had been shaken up by the fact that we had gone to a party at one of the embassies, a bridge party. I was feeling a little under the weather and besides I don’t like playing bridge in French particularly anyway. We left early and the guy who took the place at our table and his wife were machine gunned as they were crossing the square that we crossed a half hour before. It would have been us if we had been there. That got my wife kind of excited, although she is pretty good.

She was stalwart, you know, during the first coup d’état. She took in all the wives and the families–we had about six in our house and none at the Residence, I might add. So we had a house full of people. She is pretty good–not all that nervous.

Then on the second anniversary, as I said before, we got to the parade and the tribunal was up there. The President and the Vice President were in the first row, second row was the cabinet, third row the diplomats — and I was Chargé and in the third row — and everybody else was sitting there.

I saw the guy throw what I thought was a rock at the President. The rock turned out to be a fragmentation grenade … It hit all the press. I am sorry to say I didn’t realize at the time, but several of them were killed and it was kind of messy. Then I’ll be damned if the guy doesn’t heave two more grenades at us. Some misguided patriot, on the fourth one, grabbed his arm and patriot and grenade thrower disappeared in small juicy pieces together.

I had been extraordinarily fortunate because I was sitting behind the Minister of Health’s wife and she was a great big broad woman. She got pretty badly hurt but I just ruined my last blue suit and the papers I had. I,being kind of fat by this time, decided that I would simply lie on the floor for a bit, which I did. By the time I got up, I was the last one on the viewing stand….

All this time the army was there waiting in formation for the parade to begin. Ambulances came and took away the wounded and the dead and picked up the pieces. Out in the Place de la Nation again were two thousand pairs of shoes where the whole African population had run out of their sandals. I have a slide at home that I took showing nothing but shoes out there.

The whole diplomatic corps and cabinet had gone over the rear of this reviewing stand which was about, by the time you had the rail up, eight feet. They were all arms and legs. The Italian had landed on the Egyptian, and the West German had landed on the East German and there were shouting and cries. I said to myself in isolated splendor out in the reviewing stand: “I think I will go home. I wonder where my car and driver are.”

So I am walking down the steps of the reviewing stand when the Soviet Ambassador comes charging up and says, “Dwyer, I just want you to know that I would not have left the reviewing stand had it not been for the fact that my wife was with me and I wanted to get her to safety.”

And I know Sally [his wife] is in the Cameroon and I said, “Ambassador Sokolov, let’s go home and have a drink.”

He said, “Well, why not.”

So the seven of us and the Vietnamese head of security sat there and reviewed the parade. I was just dying because I knew the whole diplomatic corps was sending out telegrams and here I was stuck reviewing the bloody parade for two hours.

My wife and daughter were in the Cameroon and it, of course, hit the radio which mistakenly said a few diplomats had been killed. Sally gets in the land rover with my daughter, secretary and chauffeur charged back over to the river only to find that the border is closed and that there is no way you can get across.

Sally, therefore, hired a dugout canoe and with my secretary, who was a woman about 63, enormous, who always wore a girdle, I never saw her without one– Lavona was a lovely person, a dedicated Foreign Service secretary — Lavona was in the front end of the canoe with the paddler in the rear and my wife and daughter in the middle came across.

The next day she walks in the door and I am having a glass of champagne with the new East German Ambassador because it was his turn to call on me. We are sitting there in air-conditioned splendor drinking champagne. My wife comes in with her hair down and muddy up to her knees and she looks in and says, “Are you all right?”

I said, “I’m fine, Sally.”

And she says, “God damn you!” It can be hard on family.