The art of diplomatic relations and negotiations is as old as civilization itself. However, the State Department did not have any formal training facility until the Consular School of Application was founded in 1907. Then came the Wilson Diplomatic School (1909), the Foreign Service School (1924), the Foreign Service Officer’ Training School (1931) and the Division of Training Services (1945). By the mid-1940s, the need for an enhanced and permanent Foreign Service training center became apparent. As a result, Secretary of State George Marshall announced the establishment of the Foreign Service Institute under the authorization of the Foreign Service Act on March 13, 1947. FSI consists of five schools: Leadership and Management, Language Studies, Professional and Area Studies, Applied Information Technology, and the Transition Center.

For years, FSI occupied two increasingly inadequate high-rise office buildings in Rosslyn, Virginia, just across the Potomac from Foggy Bottom. While it became clear to many that FSI had to find a new home, the task of relocating, especially given budgetary constraints and bureaucratic resistance, was far from a done deal.

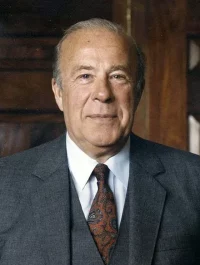

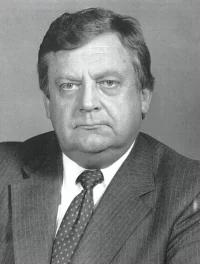

FSI was eventually able to relocate to Arlington Hall, the site of a defunct girls school and later the headquarters of the U.S. Army’s Signal Intelligence Service (SIS), largely thanks to the inspired efforts to two men: Secretary of State George Shultz, for whom the National Foreign Affairs Training Center (NFATC) is named; and Ambassador Brandon H. Grove, who became Director in 1988.

Today, the educational and training sanctuary on 4000 Arlington Blvd offers a wide variety of courses, ranging from half-day instruction on computers to training in more than 70 languages.

Interviewed by Thomas Stern beginning in November 1994, Ambassador Brandon H. Grove, Jr., who served as Director from 1988-92, discusses his frustration in trying to convince his colleagues of the usefulness of training, his design ideas to keep FSI integrated, and the fights he had within the Department when Secretary Shultz stepped down. You can read this and other personal accounts in his book, Behind Embassy Walls. Ambassador Grove died in May 2016.

Read other Moments dealing with the Foreign Service and this profile of George Shultz. Go here for Amb. Chas Freeman’s views on diplomatic amateurism and its consequences. Learn how Sputnik gave a push to teaching languages at FSI.

“There is a traditional lack of interest in training among the Department’s senior managers”

GROVE: When Secretary of State [George] Shultz offered me the directorship of the Foreign Service Institute in the summer of 1988 after my service as ambassador in Zaire, it was the job I wanted most. No other secretary was as committed to strengthening training as he and the senior team around him. Thanks to his efforts with Congress, and those of two of my predecessors, Ambassadors Stephen Low [who helped found ADST] and Charles Bray, we had before us the prospect of constructing a training facility for FSI from the ground up, at nearby Arlington Hall in Virginia. (Brandon Grove at left)

Here was probably the only chance to give training an appropriate home. I also knew that the FSI directorship until then had been a career dead-end leading to retirement but thought little about it, buoyed as I was by Shultz’s engagement and support.

My involvement with the Foreign Service Institute began in April of 1959, when I joined some twenty other recruits to the Foreign Service in the A-100 orientation seminar for junior officers….FSI was located at that time in a converted basement garage at Arlington Towers, an apartment complex in Rosslyn, Virginia [just a few minutes from the State Department]. Before that, a former private residence in Foggy Bottom served as a school for novice diplomats, and much earlier, training took place in the Executive Office Building next to the White House….

And now, while the Cold War was not yet over, one could sense that great changes were imminent and would originate in Central Europe. These, in turn, would profoundly affect training needs.…I had begun my career nearly thirty years earlier at the height of the Cold War, and would have an opportunity to apply what I had learned to every aspect of training as that struggle ended.

I did not at all anticipate the difficulties FSI would encounter once George Shultz left office.

There is a traditional lack of interest in training among the Department’s senior managers. It would be the battle of my career to maintain support for the desperately needed facilities we were planning to build at Arlington Hall.

Training must constantly change to reflect the times. No sooner has a course of instruction been designed than it needs to be reviewed for relevance and brought up to date at the edges. The cowboy in a Cormac McCarthy novel who is asked whether he knew the world would never be the same, wisely replies: “I know it. It ain’t now.” A modern-day Heraclitus, that man….

The challenge is to get ahead of the curve and find funding to match needs. While training imparts knowledge, its primary focus is on building skills…. Training at FSI is also intended to develop professionalism, the motivation that comes from being engaged in worthwhile work — with its own values, standards and rewards — that is not just another job. Two hundred and twenty years of American diplomacy are on record. FSI should be a place of inspiration for everyone who goes there. Each student should emerge with enhanced knowledge, skills, and motivation.

No other part of the State Department is capable of transmitting the values of the Foreign Service, its ethos and esprit de corps. Paradoxically, few at State think of FSI as having this function, or are concerned about perpetuating a common core of values, or even seem to care what these might be. This leaves a great deal in the hands of FSI’s staff, and never more than at a time of revolutionary change such as the ending of the Cold War which, as it happened, occurred on my watch.

“The A-100 course occupied a cavernous, windowless room with blue walls that reminded me of the hold of a cargo ship”

Two high-rise, converted office buildings in Rosslyn accommodated the Foreign Service Institute in the 1970s and ’80s. One of these was a narrow 14-story structure, which we occupied entirely. We also rented one-third of a similar building two long blocks away.

Both buildings’ elevators, which were not designed for heavy traffic, took notoriously long to arrive and caused problems of delay and frustration for students and staff each day. Anyone wanting to get from consular training to Chinese language class in a rainstorm got wet. In the main FSI building, senior management was located on the top floor, isolated from other operations in appearance and fact. Our offices had spectacular views, but were in the wrong place.

Both buildings were overcrowded. The halls were dingy, with walls that needed paint. It was either too hot or too cold in the classrooms. The furniture was terminally tacky. The A-100 course, which was conducted in the second building, occupied a cavernous, windowless room with blue walls that reminded me of the hold of a cargo ship….Despite deplorable conditions, people working there showed remarkable enthusiasm and energy. The credit for this goes to staff and students alike.

We were inspected shortly before moving to the new campus, and Foreign Service inspectors made a particular point of praising morale throughout FSI. The staff knew they were engaged in work that mattered, and their enthusiasm proved contagious.

Each year, the language school held a Christmas party in the hold-like A-100 classroom. It was crowded by tables with dishes from all over the world, prepared and served by teachers and their families from many different countries. For a day, FSI offered the best ethnic food in Washington. Such generosity comes only from people who love what they are doing and are proud of their roots.

FSI had a discretionary yearly budget of over $16 million for training, beyond the fixed costs of salaries and expenses. With this, FSI provided 1.6 million instructional hours every year. We thought of our resources as money, people, time, space, and ideas; all were in play as we planned ahead….

[We] took the senior staff each year to an off-site overnight retreat in the countryside. There, we could lean back in our chairs, discuss the present, and plan ahead. Before we left for our off-site conferences, the deans of our specialized schools and their executive directors held meetings with their own staffs to elicit ideas and build consensus on objectives and budgets. Senior managers came to these conferences with the considered judgments and targets of their staffs.

At the end of our first off-site meeting I was asked what my vision was. On a large paper chart I wrote: “One FSI,” because I was concerned about compartmentalization between our schools caused — but only partly — by the physical barriers of separate, multi-storied office buildings.

After the second off-site, I added “…doing things differently,” meaning that our training needed to reflect changing priorities at the Cold War’s end. At the third annual off-site, I wrote “…at Arlington Hall.” By then we had nearly completed construction of our new home. “One FSI doing things differently at Arlington Hall” thus became our corporate vision for four years beginning in 1988, one that was fully realized.

Following our off-site conferences, I invited FSI staff and students to a general meeting held in a church across the street from the main FSI building in Rosslyn. This church, a well-known landmark, was perched on top of an Exxon gasoline station at a major intersection. We rented it for large meetings and fondly called it “Our Lady of the Fumes.” [Also referred to as “Our Lady of Exxon.”]

At these meetings, we provided summaries of what took place at the off-site sessions, described the conclusions we had reached about future directions, and tried to build broad-based support. When we were routinely inspected in 1991, Foreign Service Inspectors took a close look at this process and, in their report, cited it as a model for other State Department bureaus to emulate because it uniquely brought goals, priorities, resource requirements and responsibilities for implementation together in one process.

This inspection was the first time a State Department bureau, as opposed to an overseas post, had been singled out to receive the Department’s annual “Secretary’s Award” for excellence in management. Here, immodestly, is what was said about me: “Morale at FSI is high. [The Director’s] confident and cheerful bearing, his enthusiasm and genuine sense of job satisfaction are infectious. His style is consensual; he is a good listener; he is willing to make decisions and take risks.”…

We were independent of other agencies, concentrating on our educational and professional objectives, but we consulted them and got what guidance we could from them. We were, unfortunately, never able to create a board of advisers drawn from other agencies such as Agriculture and Defense, or even from our foreign policy sisters in USIA [U.S. Information Agency] and AID [Agency for International Development], a board that would support and help us shape our training. No one at sufficiently high levels in these bureaucracies wanted to spare the time.

At State and elsewhere, managers remained indifferent to the training function, except when it came to their particular concerns, as in developing specific and urgently needed language, consular, or administrative skills.

“The ambassadorial seminar, the A-100 course for new officers, and the DCM seminar formed a training triangle”

Our first task, always, was to maintain the quality and relevance of 1.6 million hours of instruction annually.…We expanded and improved our executive development and leadership programs for supervisors at all levels. We started a course for people in their first supervisory responsibilities, and improved upon already sophisticated courses for deputy chiefs of mission (DCMs) and ambassadorial seminars for newly appointed chiefs of mission. These were about leadership and effective management of resources. Attendance was mandatory.

Recruiting for our other leadership offerings was an uphill struggle, because most State Department people incorrectly believe they are already good managers. In my view, the ambassadorial seminar, the A-100 course for new officers, and the DCM seminar formed a training triangle. Each needed to understand the obligations and concerns of the others and how they were linked in differing roles. The lines connecting them bound together people at varying stages in their careers, yet performing within a common area of professional standards and expectations.

My colleagues at FSI instilled these standards and provoked discussion, at each level, of institutional values and responsibilities to others: the President, Congress and ultimately the American people. From a training standpoint, FSI becomes the link between ambassadors, DCMs and junior officers.

I met three times with each A-100 class: on their first day to welcome them and set the tone; during a brown bag lunch at midpoint to get their reactions to the course and field their questions; and at graduation to talk about assignments they had just received, some of them as exotic as my own, in earlier days, to Abidjan.

It mattered a great deal who the FSI course leader was in terms of what that individual could impart by word and especially attitude, over ten weeks [now six weeks], to such an eagerly receptive group. I have consistently been impressed by the high caliber of people joining the Foreign Service, and by speedy progress in achieving racial and gender balance. We could not have had better women and men as trainers.

I joined the DCM Seminar at its off-site session on the first day, and spent an afternoon and dinner with these prospective deputies to ambassadors to talk about their future roles and relationships, emphasizing the central management responsibilities of the DCM. I talked at length about the ambassador-DCM relationship, the most delicate and potentially troublesome pairing of people in diplomatic life. There is a saying that the largest graveyard in the Foreign Service is filled with DCMs….

During the late Reagan and Bush administrations, I designed and led 13 two-week seminars for over 150 newly appointed ambassadors and their spouses. The indispensable private sector co-chairman, Langhorne (Tony) Motley, and I emphasized the leadership responsibilities of an ambassador over all elements of the U.S. government at the embassy, especially the intelligence function, and the critical nature of a successful relationship with the DCM, “who, aside from your spouse, is likely to be your only other true friend at post,” to quote Motley.

We stressed to politically appointed ambassadors, initially suspicious of the Foreign Service, that the future prospects of the embassy’s professionals rested on the success of the ambassador. They could be counted on for support, as well as advice worth listening to….

“It is Secretary George Shultz who is the godfather of this facility”

By the time I arrived at FSI in the summer of 1988, the State Department had obtained agreement that land for a construction site would be transferred to it by the U.S. Army, then occupying Arlington Hall as a signals intelligence facility, INTSCOM.

There was already a footprint for new buildings, and a comprehensive construction budget. We worked closely with Congressman Frank Wolf (Republican, VA), in whose district this facility was to be built. By 1988, we thus had a concept, Congressional backers, and the full support of George Shultz’s State Department from the top down….

My greatest concern at FSI throughout my tenure was the design and construction of Arlington Hall, a task that became increasingly time consuming. My predecessor, Steve Low, took the first steps in this direction by finding the Arlington Hall, Virginia, property on Route 50 between Glebe Road and George Mason Drive, which is now the site of the new institute [a 20-minute shuttle ride from the Department]. Ronald Spiers, the Under Secretary of State for Management, supported Steve at every turn.

But it is Secretary George Shultz who is the godfather of this facility. He dealt with Congress on the issue initially, and made the case for it because he believed in the need for training. Deputy Secretary John C. Whitehead once told me Shultz considered himself to be primarily an educator, despite several top-level government posts after his deanship of the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago. Whitehead said Shultz regarded the FSI campus as his legacy to the State Department.

It fell to me to take the project through the design, funding and construction phases. Our concern was to design a facility that made sense in training terms. We placed language training and testing next to each other, and area studies alongside. We located the Director’s office and administrative offices at the heart of the complex. We put the classrooms for the A-100 course for junior officers nearby, so they would feel they were at the center of our activities.

We installed a satellite dish to deliver inter-active video training, live, to Foreign Service posts throughout the world. We wired the new buildings with as many computer outlets as possible, even though we knew we could use only a fraction of this capacity initially.

We required the architects to design the buildings and interiors to provide classroom flexibility in size and function, through movable panels, which would permit our successors to adapt readily to changing requirements. The cafeteria would be large, modern and open to sunlight and the broad meadow outside. The temperature could be controlled in every room, and there would be a centrally regulated clock in each part of the facility. Controlling the clocks was a big point with me. The State Department has hundreds of wall clocks, few of which are accurate. I will never forget overhearing a visitor say in an elevator, “These people don’t even know what time it is!”

“Our anticipated financial resources were reduced, requiring us to scale down plans”

On October 25, 1989 the U.S. Army formally transferred 72 acres of Arlington Hall to us, and we began our work. Arlington Hall had been built in the early 1920s as a girls’ finishing school. It was never very successful.

The campus then consisted primarily of one yellow brick building, “Old Main,” which still stands, a gymnasium, and a riding stable which no longer exists. The white-clad ghost of a girl named Mary, who according to lore became pregnant and committed suicide, is said to roam the halls where we now have the Overseas Briefing Center. The school ran into financial difficulties during the Depression. The property was ideally situated near Washington.

The Roosevelt administration took it over in the early 1940s to house the Communications Analysis Unit, the operation that played a key role in breaking the Japanese “Purple” code before World War II. Arlington Hall remained a cryptographic installation until its Army unit left for larger quarters in October 1989. When the State Department took it over, it reverted to its educational function, an appropriate closing of a circle in Arlington County’s history.

We began by demolishing more than fifty World War II barracks in run-down condition. Once when [Deputy Director John] Sprott and I went out there, we found ourselves standing in the rubble of what had been the officers’ club — the last building to be abandoned by its former owners, of course. I saw a scrap of wallpaper on the ground, picked it up and had it framed alongside a picture of the pile of rubble as a salute to the past….

About one-third into the project, our anticipated financial resources were reduced, requiring us to scale down plans for the three wings that now house the main training activities, and eliminate a fourth wing entirely….We wanted to put a pond in a natural drainage depression in the middle of the large green meadow, but that too, had to be given up. Someday I hope it will be built, because for engineering as well as aesthetic reasons it belongs there.

We made arrangements to acquire a seated statue of Benjamin Franklin, then lost in shrubbery in front of the State Department’s entrance, and to place it prominently in the main court where it has become a magnet for class pictures and the simple pleasures of sitting on a bench with Ben, the first and one of the most effective of our nation’s ambassadors.

So many of our limitations and problems at Rosslyn served as cautionary lessons in our planning for Arlington Hall. Having to get from one FSI building to another in open weather in Rosslyn led me to the idea of building two glass covered bridges to connect the buildings on our campus.

Now, every part of FSI is accessible without having to go outdoors, and those who walk the bridges can see the trees and colors, the rain and snow. These connections are also important to the concept of “One FSI.” I insisted the facility be seen as a whole, not as a collection of discrete training activities, and its buildings had to reflect that vision. We wanted people to feel they were all part of a single, integrated activity called foreign affairs training….

We involved everyone at FSI as we developed our plans. We wanted staff and students to feel they had contributed to the design of the facility in which they would work, and we got excellent ideas from them. As we developed this project at Rosslyn, excitement about what the future would hold began to mount. Offices and people outside of government became involved and were crucial to the project’s success.

One such group was the Virginia Historical Association, in Richmond. They required us to keep the old main building of the girls’ school. The Association found it to be of historic value as architecture of a bygone era, and a landmark in military history for the cryptographic work done there during World War II. This requirement presented a challenge of its own: How could the large, yellow brick building be integrated in a functional way into a newly built red brick campus?

In fact, saving the old building turned out to be a major asset to the complex for its usefulness and dignified appearance that evokes an earlier era. There are two white and ugly cottages abutting Route 50 we were also obliged to keep. The Historical Association believed they were Sears Roebuck prefabricated houses dating back to 1929, and therefore of historic interest.

I found it curious, even unsettling, that something built in 1929, the year of my birth, was already designated a “historic” site. To this day, they stand there and house the property managers. [Now completely redone, one houses ADST.] We also had to keep the narrow little gymnasium, because it had been part of the girls’ school….

“George Shultz decided that ‘Foreign Service Institute’ sounded too parochial”

One of the requirements, in a venture like this, is to hold an advertised open meeting for neighborhood residents. We held ours in a rented church in Rosslyn in the winter of 1989, on a particularly cold evening as it was beginning to snow. About fifty people braved the elements and showed up. I chaired the meeting. Some expressed reservations and were antagonistic about such potential problems as traffic, parking, destruction of trees, noise, and the impact on back yards adjacent to the property.

One long-time resident was particularly incensed, and condemned our project roundly. I recognized an elderly woman sitting in the front row, having no idea who she was. She introduced herself as Louise Hale, telling us she had graduated from the Arlington Hall girls’ school.

Silence descended. She went on to say she thought our proposal was wonderful and had the full support of the Alumnae Society. For us, this was the crowning moment. We knew the community would be behind us, and they were. God bless Mrs. Hale! We invited her and all other graduates of Arlington Hall we could find to our inauguration as a successor educational institution, and they came.

When George Shultz first presented the concept of a training center to Congress, he decided that “Foreign Service Institute” sounded too parochial. He wanted to emphasize that the new facility was not just for the Foreign Service, or even primarily for the Department of State, but rather that it would serve all agencies of the executive branch. He believed this approach would gain support from Congressional Budget and Appropriations Committees.

For that reason, the name “National Foreign Affairs Training Center,” a tortured appellation, came into being. People usually refer to the campus now as Arlington Hall, and still call it the “Foreign Service Institute,” but formally it is the “National Foreign Affairs Training Center,” with the unfortunate acronym “En-fatsy” [NFATC]….

“The low level of interest in training on the part of the Department’s new senior managers became evident”

The [George H.W.] Bush administration brought with it unexpected problems for FSI and the Arlington Hall construction project. The transition from Secretaries Shultz to [James] Baker imposed such sweeping changes in senior appointments one would have thought the Democrats had won. It took us at FSI several months to understand the magnitude of what had happened.

Under Shultz, we had thrived in heydays of support for training and, in hindsight, were slower than we should have been to realize that it was going to be different under Baker. The signs were there.

As Ivan Selin, the newly designated Under Secretary for Management, was preparing for his Senate confirmation hearings, I invited him to visit FSI, see what we were doing and receive briefings on the construction project from a training perspective. He chose not to, and in fact did not come to FSI during his tenure in order to meet the staff, walk through the facilities at Rosslyn, or receive a comprehensive briefing on the Department’s training and its future. He appeared once to visit the Russian language section, claiming enough skill in Russian to “get the job done.” The linguists were not impressed.

Ivan Selin had been one of [Secretary of Defense] Robert McNamara’s “whiz kids,” the young, highly intelligent and impatient systems analysts in the Defense Department in the mid-1960s whose quantification skills revolutionized abilities to deal with enormous amounts of information in systematic ways….

During his first off-site management meeting at a country retreat called The Woods, Ivan indicated that funds for Arlington Hall were not a top priority for the Department’s building program. The Department was working under serious budget constraints, I argued, but the development of a new training facility was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and Congress had already committed itself to funding the project. I left this session disturbed about our prospects and it soon became clear the campus project was in trouble.

After the departures of Shultz, Whitehead, and Spiers in early 1989, the low level of interest in training on the part of the Department’s new senior managers became evident. Before the changeover, I met weekly with Shultz and his Under Secretaries, usually on a Friday morning for fifteen minutes, to bring this small group up to date on training and get their views on issues as they came up. Sometimes I would take an FSI colleague along to give the Secretary a first-hand report, and make our staff visible to him.

This atmosphere evaporated in the new administration. There were no regular meetings on the Seventh Floor [where most Department principals, including the Secretary, have their offices] to address training or progress on the construction project.

What we did encounter was unexpected opposition to construction of the training facility on the part of Ivan Selin, and his new Director General, Edward J. Perkins…. Selin, who had no previous State Department experience, determined before his arrival that the Foreign Service Institute should be made part of the Director General’s office, rather than remain an independent entity reporting directly to him.

In my first meeting with Ivan, I argued that such a move would be a mistake for many reasons, not least that the training staff was larger than the Office of Personnel and their combination would be unmanageable….

A fundamental flaw in this proposal, I suggested, would be elimination of a natural and healthy tension between responsibilities for assignments and training. If FSI were to become integrated into the Director General’s office, the assignment function, with its real and imagined pressures, would always win over training.

It was already difficult enough for FSI to insist on training in discussions with the assignments division, whose first priority was to fill vacancies. Training does consume time, but to assign people when they are inadequately prepared for their responsibilities is wasteful and unfair to the employee and prospective supervisor.

Selin’s argument boiled down to the fact that since we trained people, anything to do with people belonged under one supervisor, the Director General. It was the same argument that caused the Medical Division and Family Liaison Office to become appendages of Personnel, although the issues in these instances are different….

“There is an anti-intellectual bias in the State Department, which is surprising given the nature of its work”

As Director of FSI, I was nonetheless cut off by Ivan from senior management councils, no longer participating in weekly management staff meetings….

Selin viewed the training function largely as “nuts and bolts” and “dirty fingernails” work, as he described it to me. He saw FSI’s function primarily as providing language training, and instruction in technical matters such as secretarial, consular, and administrative skills. This view put FSI’s Senior Seminar and Center for the Study of Foreign Affairs in jeopardy. Obtaining funds for these programs was a continuing challenge, and eventually the Center was abolished by Selin’s successor, John F.W. Rogers.

Secretary Baker took an hour and a half to visit FSI early in his tenure. He met the senior staff and gave a warm talk to combined A-100 and DCM classes on his views of the role of training in foreign affairs, all of which was helpful. Baker was personally supportive of training. Not a manager by instinct, he had policy issues all over the world demanding his attention as the Soviet Union imploded.

Selin visited the campus construction site once or twice, and remained skeptical about the need for such a project, although by this time demolition of most of the old barracks had taken place and initial funds were committed. Ivan told me that if the campus were not so far along, he would have stopped it. The Director General was equally, and loyally, skeptical.

There is an anti-intellectual bias in the State Department, sometimes among its best and brightest, which is surprising to encounter given the nature of its work. This bias is most strongly held by people responsible for the budget, whose inclinations are to shy away from priorities in training beyond its trade school aspects.

When the Department’s leadership is not vocal in supporting training, which means insisting on funds for it, and that training be provided, the system takes over. Training becomes a low priority, particularly in the personnel function, of all places, which feels the heat to fill vacancies promptly, often disregarding its responsibility to insure that people are qualified and prepared for their assignments.

If one were to assign blame, it would be to the Department’s Foreign Service Officers themselves who often care little about their own professional development through training, greatly needed in management and leadership skills, much less that of their subordinates.

Getting a warm body into the job, as the expression goes, is the short-sighted goal. The howls and screams come later, when it is discovered that these hastily placed warm bodies lack needed skills and are performing poorly. And nowhere is this more evident than with secretarial and administrative staffs, where poor performance is highly visible. Not fair!

“The biggest problem was opposition by Management to the construction of the training facility”

Selin’s successor, John F.W. Rogers, adopted the views of his predecessor, by whom he had been briefed…. As soon as he was confirmed, Rogers tried to subsume FSI under the Director General. This was once again blocked by Congress for the same reasons. All of this was going on while we were struggling to build the campus, which was further along when Rogers became Under Secretary. Rogers went to the campus site once, briefly, during my tenure to make sure the Director’s office was not too large, and thus a potential embarrassment to Baker. It wasn’t….

John Rogers eventually reached a more thoughtful assessment of FSI’s role. He came to understand the relationship between training and achieving the Department’s objectives. In a meeting with senior FSI staff shortly before he resigned, he said that to subsume FSI under the Director General would have been a mistake. He had listened too closely to Selin on this issue, he admitted. By then I had left, categorically excluded by Rogers, as before, from management’s meetings and decisions regarding training.

By far the biggest problem for us at FSI during the Bush administration was opposition by the Under Secretary for Management and the Director General’s office to the construction of the training facility. Each year, the State Department had to obtain appropriations for the project. This gave opponents at State opportunities to shoot it down. Twice, we all but lost the funding, once in 1989 and again in 1991, both times during Ivan Selin’s tenure…. The second time we nearly lost our funding, in 1991, seemed a fatal blow.

I attended a budget meeting in Selin’s office during which he announced that the Department’s request for funding the training center would be dropped, despite arguments to the contrary from Admiral Fort, whose Administrative Bureau was responsible for construction, and myself. The matter was decided. He would shortly be going to a budget meeting in Deputy Secretary Lawrence Eagleburger’s suite to which I was not invited. I left Selin’s office completely discouraged. There would be no chance for me to make FSI’s case to Eagleburger because I would not be attending the meeting.

The dream of Arlington Hall was over, and it was the State Department, not OMB [Office of Management and Budget] or Congress, that was ending it.

I walked down the hall to Larry’s office and asked his secretary for stationery and an envelope. Seated in the Deputy Secretary’s empty conference room, which I had first come to know thirty years earlier as a junior staff assistant to Chester Bowles, I wrote a note to Larry saying that something immensely important to the Foreign Service was about to be decided in his budget meeting.

If we did not take advantage of our present opportunity at Arlington Hall, we would never find a comparable site, or get money from Congress. By surrendering our funding request, we would deny the Foreign Service much of the training a new world situation demanded. A supportive Congress would be annoyed. I put my note in the envelope and asked his secretary to take it in to him. I never heard a word from Eagleburger, but the funding remained in place.

The story of the new campus has a happy ending. When I left FSI in 1994, construction was 90% completed, nearly four years after George Shultz had drilled the first test hole. It is now a thriving facility, and I find it immensely satisfying, even thrilling, to watch students walk through the glass connecting passageways to their classrooms. The National Foreign Affairs Training Center is one of the great domestic accomplishments of the State Department, and I feel privileged to have had a role in its creation. How rare it is to leave something behind in bricks and mortar!

The most intractable problems facing Department training

Here are the two most intractable problems in the effort to provide proper training in the Department of State. First, except for rare leaders like Secretary Shultz, there is little support and often disregard for training by the Department’s senior managers. An ethic in the State Department validates the avoidance of training because there are always “more important” things to do. These matters are called “substantive.”

Training, moreover, is not in the present scheme of things seen as career enhancing. Long-term training, as in the Senior Seminar and advanced economics program, is too often viewed as taking up valuable time that could be spent on activities thought to be judged more favorably by promotion boards who are, in fact, supportive of training assignments and reward them.

Second, training too often is not linked to the assignment process. I would like to see specific training requirements mandated for every job in the Department’s civil and Foreign Services as prerequisites to be met by anyone filling a given position. Only if training requirements are established for each job, and insisted upon by personnel managers, will the State Department change its culture and place training in its proper place in career development.

When a position description shows up on Personnel’s computers, the training courses needed should appear alongside and be required. No work in the Department can be considered too unimportant to require training, and employees need training throughout their careers as their assignments and responsibilities progress.