Sudan’s long history has been riddled with internal conflict. The United Kingdom and Egypt controlled Sudan for the first half of the twentieth century, then agreed to cede it self-government in 1953. In December 1955, the premier of Sudan declared unilateral independence. The newly independent Republic swiftly fell into a pattern of civil wars, coups d’état, ethnic conflict, and government instability that continues to affect the region today.

The government that formed in 1956 led by Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari was short-lived, soon to be replaced by a fractious and ineffectual coalition of conservative leaders. In 1958, the forces of Lieutenant General Ibrahim Abboud overthrew the parliamentary regime in a bloodless coup. Abboud worked to improve Sudan’s economy and foreign relations but did not return the country to civilian rule. Resentment over repressive domestic policies began to build, especially among non-Arab ethnic groups in the south and student activists, leading to riots and strikes. James Moceri served as Public Affairs Officer (PAO) at the United States Embassy in Sudan’s capital of Khartoum from 1962 until 1964, during which he witnessed the beginning stages of an overthrow of the government. Moceri recalled his experiences involving Sudanese unrest in an interview with G. Lewis Schmidt in May 1990.

To read more about Sudan, Africa, post-colonialism or coups, or to read James Moceri’s oral history, please follow the links.

“Washington viewed the Sudan with complacency as a quiet backwater country”

James Moceri, Public Affairs Officer [PAO] for Sudan, (1962-1964)

MOCERI: Evidently Tom Sorensen [Thomas C. Sorensen, United States Information Agency Deputy Director, 1961-1965] had decided in his wisdom that I should fill the first available opening in the field, the PAO position in the Sudan, replacing Henry Hudson. (Moceri is at left.)

Especially after my briefings in the Agency [USIA] area office and at [the Department of] State, I felt rather strongly that my work in my earlier field assignments and my two years of Washington duty had earned me the right to a more important assignment than the Sudan. I knew nothing about that part of the world or the Arab world and Northeast Africa.

It was unmistakably clear from my briefings that Washington viewed the Sudan with complacency as a quiet backwater country that was not expected to present any problems. All I really got in terms of briefings and preparation was “You go out there and have an easy, pleasant time of it.”

This was a State Department officer, Cleo Noel [Cleo A. Noel, Jr., seen right], if I recall correctly, that was his name. Many years later, he was an ambassador in Khartoum and was killed by a terrorist.

And he said, “We’re perfectly happy with that regime [Ibrahim Abboud’s military regime]. We’re perfectly happy. We have no problems. You’ll have a nice, quiet time there. You won’t have to do a thing. You just put in a couple of years. It’ll be nice.”

It wasn’t my idea of what I ought to be doing at that stage of my life in the Foreign Service. I didn’t know anything about the Sudan. I got there in November of ’62 and remained for two years as PAO.

In terms of guidance from the remote Washington vantage point, everything was going fine. There were no problems. We had no problems with the Sudanese Government . . .

Even if I were the most brilliant man in the world, I still shouldn’t have been put into that kind of a situation because there were too many problems. One can say, “Oh, but you’ve got all new people. You can mold them the way you want.”

No, that’s not the way to do business, in my book. And there had been nothing that prepared me for USIS [United States Information Service] Khartoum.

I knew that I had a lot to learn about the Sudan and our USIS program before I could venture to open my mouth about anything in the ambassador’s staff meetings. The bemused, seemingly indulgent contempt with which senior Embassy personnel looked upon USIS and its activities was quite transparent . . .

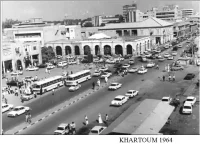

For the current fiscal year any new program initiative was virtually impossible, thanks to insufficiency of funds. So I went about the business of trying to establish contacts with people, find out what was making this country tick, and so on. Thanks to some of the local staff, I met a number of people and most importantly some who had been senior civil servants trained under the British. (Khartoum in 1964 at left.)

Well, one fact I learned that was especially interesting and indicative for me: the Abboud military regime had gotten rid of over 65 percent of all the civil servants trained by the British. One may say what he wants about British imperialism and British colonial administration, but people they trained they generally trained pretty well. And these were good people.

And I thought, “Well, something will have to give in this situation. These military people won’t really know how to run a government. They get rid of all their trained bureaucrats. And bureaucrats have a function, after all.”

And I got in touch with university students. Got to know quite a few of them, including a few university girls, and then southern students, the blacks of southern Sudan.

I was really fairly careful at this point, because I realized that, like all authoritarian regimes, this regime could be quite restrictive and very intolerant of certain things. So I moved rather carefully.

I did quietly arrange for people to come out to my house for dinner, music or just conversation. We talked of their problems, and I learned much about their country. Within four months I came to the conclusion that this regime’s days were numbered.

“The conflagration will take place. And this regime is finished”

So I sat down and wrote a lengthy paper on the coming coup d’état, the conditions that were its seed-bed and why it would happen. By this time I’d become quite friendly with the CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] station chief, in part because of the warm friendship between our wives.

One day I said, “Look this paper over because I want to give it to the ambassador. I think it’s a good reading of the situation, as I know it. And I want your reaction.”

He read it and he says, “You’re right. You should give it to the ambassador.” And I figured, well, the ambassador will send it in. The ambassador was William Rountree.

And I didn’t know, before I went there, that Rountree had been ambassador to Pakistan and had been removed at the insistence of Lyndon Johnson when Vice President Johnson on his swing through the South committed several gaffes—to the barely concealed delight of the accompanying American press corps.

Rountree had had a remarkable career in the [State] Department and he was very able. But at this point, I think he was gun-shy. He just wanted everything quiet, didn’t want to raise any hackles or call undue attentions to himself.

The argument I advanced in the paper was along these lines: “The government has alienated every segment of the public sector, apart from the army, and that too may be in question. There isn’t an element in this country that supports this regime anymore.”

And I added, “Some incident will occur. Probably something like a student being killed or something like that. It’ll be just like a leaf falling somewhere. The conflagration will take place. And this regime is finished.”

Well, my guess is that Ambassador Rountree simply filed the report, buried it. At the time I was still very much the newcomer, our relations were formally correct but just that.

Rountree (seen left) was as always correct, very courteous, and generally quite a reserved Southern gentleman. I hesitated to ask about my paper and he never mentioned it. But word of my thesis did get around; you know, the wife of one of the political officers needling: “Oh, Moceri and his revolution.”

And I was pointedly reminded of this when the revolution, coup d’état took place.

And it happened some eighteen months later. The regime just disintegrated when it was confronted by an angry but unarmed mob, perhaps because it had no stomach for a bloody massacre.

Well, I felt this was simply a question of my objectively trying to read what the climate, political climate, of opinion was. And that this was one of my proper functions. And I felt that the political people weren’t doing this.

All I was hearing were expressions of considerable satisfaction with the way things were going, in spite of the growing unrest in the South in the spring of 1963. The ambassador came to me at that time and said, “Why aren’t you doing more to persuade the people, the Sudanese people, that we are giving our assistance to them?”

I said, “Because they don’t believe it. And there’s no way of making them believe that. They see our assistance going to a government, which then diverts the equivalent amount of resources for its own little war in the southern Sudan.”

The estimates in 1964 — when I left — were that already half a million people had been killed in that civil war. There had been, I think, a total of a couple stories in The New York Times.

Hedrick Smith [a journalist at The New York Times, seen right] came up from Cairo to cover the unfolding crisis in the South. I gave him a complete briefing on the southern problem, the problem of Arab-black relations in the Sudan, of the missionaries and so forth.

He said, “Don’t give me so much detail. I can only file a 500-word dispatch a day. I can’t explain all this in 500 words.”

I said, “Well, that’s your problem.” But he was very good about it. I went at considerable lengths to brief him.

“In the meantime, all hell had broken loose…”

On our wedding anniversary — I’m sorry for introducing this personal note; there always has to be some personal element in this — I was taking Modesta [Moceri’s wife] out to dinner; one of the few times we went out to dinner in the Sudan. And there was a restaurant a block away from the Embassy, up on the 14th floor of this new building.

I’d made an 8 o’clock dinner reservation, but I got home later than I had expected. We hurried back to the center of Khartoum and drove to a round circle from which we could go directly down a street to the restaurant and Embassy. We were about five blocks from the Embassy, at the time.

The street was completely closed. There were tanks all around. Every car parked on that street, as far as the restaurant, and the Embassy were ablaze.

Had I gotten there fifteen minutes earlier, either we would have been in the car and injured or killed, or the car would have been burned while we were having our dinner. And we would have been stuck up there.

In the meantime, all hell had broken loose: gunfire, a seething mob, tanks maneuvering, troops getting into position around government buildings. Dropping my wife off at a friend’s house, I picked up my Information Officer and circled the city for several hours, gathering impressions and information.

From that moment, the 22nd of October, all foreign missions lost all contact with the Sudanese. Our CIA lost all its contacts with the army and the police. The ambassador lost all his contacts.

Things were so bad that the British ambassador was calling our ambassador to find out what he knew and our ambassador was calling him. Nobody knew. Curfew was imposed. Yet I went out every night, seeking information from my Sudanese contacts.

This was the coup that I had foreseen and it had started with a protest staged by university students. Three university students had been killed by the military because they were protesting certain government actions. There was sporadic gunfire, and some shots came through Embassy windows. Our flag was pulled down. Large angry crowds milled around our building all day.

But I thought and pointed out to my colleagues, “You know, it’s all very methodical. All you have to do is get here at 7:00 and the mobs arrive at 8:00. Then they go off at 3:00. And then you go home. So there’s no real danger.”

With the curfew, nobody traveled. Yet I went out, for more than a week, every night. And I’d run the barricades and the check points. I’d come in to the Embassy in the morning and report to the ambassador on what I’d learned the night before from my contacts.

Because I still had my contacts, and I thought they were good. My best source was this one person, who said to me, “I’m in hiding. I don’t want to be part of the new government because I don’t approve. But here is what I’m learning.”

So I’d brief the ambassador. He’d call in his secretary and dictate a telegram to Washington. That was the one communication for the day with Washington. After a week, he got pretty nervous about it.

And he said, “You know, I don’t want you to risk your life just to take…”

I said, “It’s all right. If I don’t go out you’re not going to learn anything. And I’m careful.”

You know, as I drove down any street I’d make sure that I had a place to turn around if I suddenly encountered something suspicious or threatening.

“In that kind of closed society you have to take certain risks”

Well, that was over, and I soon left Khartoum, with the new government installed and taking actions against our interests in the Congo. Six months later, I saw Ambassador Rountree in Washington. He didn’t remember that I had been there during the coup. I was appalled.

He had, incidentally, in early 1963, authorized only me to address any Sudanese group on the question of the blacks in America . . . The Embassy had been invited to address a group of very prominent Sudanese on the problems of the blacks in America. It was not an invitation the Embassy could refuse.

The DCM [Deputy Chief of Mission] was designated to speak on behalf of the Embassy. The ambassador asked me to draft a speech for the DCM and I was honest in developing my account of the nature of the problem and the prospect for the future.

I talked about the problem of the blacks, the problem of political power, the riots in American cities; you know, things were burning. I said there would be a lot more burning until the blacks realize they have to organize themselves politically. This is the way you got to power. You acquire power in a democratic country through political organization. And I pulled no punches.

I knew what the problems of the northern Sudanese were, what troubled them. They were afraid, because of their color, that we Americans would look on them as blacks . . . In this respect, I had played a really useful role. I had a lot of people out to the house for all kinds of briefings on these particular problems.

My time came, and, as I say, I left.