Rebuilding Rwanda after the genocide was no easy task. USAID tasked George Lewis to head up that agency’s efforts to help a nation heal after one of the most horrific episodes in recent history. He faced extreme ethnic animosity, a destroyed country, and an “epic event in the history of human movement,” the return of a million refugees.

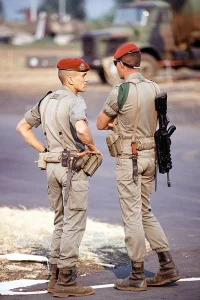

In April 1994, members of the numerically dominant Hutu ethnic group in Rwanda began a genocide against the Tutsi minority and any moderate Hutus who defended the Tutsi. Rwanda had struggled with a longstanding ethnic hatred between both groups, a hatred that was exacerbated by Belgian colonial rule, which had historically empowered the Tutsi minority. In 1994, the shooting down of the plane of Hutu Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, and the insurrection of Uganda-based Tutsi refugees, were used as a justification for the killing of the Tutsi population. It is still not known who shot down the plane, but what is known is that approximately 800,000 Rwandans were murdered in a short, 100-day period. The response of the existing UN peacekeeping force was valiant but woefully inadequate, as its commander later detailed. France mounted a belated and controversial intervention, with primary focus on protecting French citizens. The genocide ended when predominantly Tutsi forces under Paul Kagame retook the country, prompting a massive outflow of Hutu refugees. Rwanda became a symbol of the failure of the international community to act.

George Lewis was named head of the USAID mission to Rwanda in 1996 after 25 years with the agency. Lewis discusses the difficulties in reconciliation and the successes of USAID in a time and region marked by despair and tragedy. In a 1998 visit to Rwanda, President Clinton declared, “We can and must do everything in our power to help you build a future without fear, and full of hope.” It was George Lewis’s task to help deliver on this promise. Lewis’s interview was conducted by John Pielemeier on January 11, 2018.

Read George Lewis’s full oral history HERE

Excerpt:

“My first sight was the exterior of the USAID office. It was a two-story building — not large, not sprawling — and the outside walls were riddled with bullet and shrapnel pockmarks.”

An ambassador, and a USAID director, on a hit list: “I don’t know that the mission was officially closed. However, it was non-functioning during the height of the genocide. American and Rwandan staff were no longer there. The office had been raided and anything that was portable and of any value had been carted off by the Hutus involved in the killings. They also ransacked Rwandan government offices, and destroyed buildings and other infrastructure.

My first sight was the exterior of the USAID office. It was a two-story building — not large, not sprawling — and the outside walls were riddled with bullet and shrapnel pockmarks. It was located right in the line of fire during the 1994 Tutsi invasion from Uganda. I believe the Hutu Interahamwe were holed up in the parliament building and were exchanging artillery fire across town at the Tutsi-occupied military barracks just above the USAID office…. There were bullet holes in our bedroom drapes in the director’s residence just down the road. The streets of Kigali had been cleaned up by 1996, but the town itself still showed considerable destruction: no street lights, shot up street signs, abandoned buildings, little commerce. Across the country, devastation of physical infrastructure was widespread.

Your question [about hit lists after the genocide] does make me chuckle because the embassy had very good intelligence, and it came to light the Hutus had put prices on the heads of the ambassador and me. When the ambassador mentioned this to me, he said he was piqued. “Ah”, he said, “They’re not high enough. I’m worth more than that! Besides, the Hutus couldn’t afford to pay it!” (The bounty was about $15,000 on the ambassador and $10,000 on me.)

My first day on the job, passing the pockmarked walls of the mission and entering into the reception area, I noticed a plaque on the wall above the door. It was a valor award from AID Washington commending 15 or 20 Rwandan employees by name, listing them on the plaque for their bravery and dedication to USAID just prior to and in the aftermath of the genocide…. A number of the names had been scratched out. I hadn’t even walked in the door, and here is this defaced plaque intended to honor our local staff. This was my first sense of the exceptional team building challenges that lay ahead for me and for all of us. So at our initial full staff meeting, I asked the Rwandans if the scratched up plaque at our entrance was the first impression we wanted visitors to have of us. They all agreed, “No.” So I offered to take it down, they agreed, and I put it in a locked safe in my office.

They [the scratched-out names] were thought by some of their Rwandan colleagues to have been complicit at least, if not participatory, in the genocide. Some were merely family members, relatives, of those who had purportedly committed killings. It seems safe to say, that the names scratched out were Hutus and those on the staff who did the defacing were Tutsis.”

“This became an assignment that would call on everything I had ever learned over 25 years with AID.”

A million refugees flooded Rwanda, all on foot: “In that first

conversation he and I had, Ambassador Gribbin articulated three overarching objectives or “tasks”, as he lightly termed them. I think of them as the “3 Rs” — Refugees, Reconstruction, and Reconciliation. These three, as he points out in his book, are linked, but without return of the refugees, the other two Rs — reconstruction and reconciliation — would not, could not, occur. Return of the refugees, daunting as it was to contemplate, had to come first. I should mention that I also received guidance from the Africa Bureau of AID. This became an assignment that would call on everything I had ever learned over 25 years with AID.

Over the next few weeks a million refugees flooded Rwanda, all on foot. Young kids were tied to parents on long strings so they wouldn’t be separated. The roads were impassable to vehicles. I think of it as an epic event in the history of human movement. By far the large part of it occurred over the course of days, trailing over a few weeks. The population of Rwanda at the time was 8-10 million people, with a million more flooding home.

In short order, I received one of those late night calls from Washington that directors sometimes get, at 2 a.m. to be precise. “Oh, what time is it there?” asked the home office. They called to inform me that our budget had just jumped from $4.5 million to a fiscal year 1997 level of $125 million. $125 million was worth getting out of bed for!”

Drafted by Connor Akiyama

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, Oberlin College 1962-1967

MA in Developmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1969-1971

Joined USAID 1971

Mbabane, Swaziland—Assistant Program Officer 1973-1975

Washington, D.C., USA—Morocco Desk Officer-in-Charge 1978-1983

Washington, D.C., USA—Deputy Director of East Africa Office 1993-1996

Kigali, Rwanda—Mission Director 1996-1999