Allan Reed’s extraordinary relationship with Sudan can be traced all the way back to the late 1960s, when he joined the Peace Corps as a twenty-something university graduate. Volunteering for three years along Ethiopia’s western border to assist Sudanese refugees fleeing the conflict of their homeland, Reed became highly invested in the country and its people. Following this service, he walked over 3,000 miles through Sudan with the people of the Anyanya Movement and Dr. John Garang. He worked with both the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the World Council of Churches to film and research the conditions he observed.

Soon thereafter, Reed joined the Foreign Service, taking postings in Mauritania, Swaziland, Guinea, Russia, Sri Lanka, and Senegal, before finally making his way back to Sudan. There, he worked closely with Dr. John Garang and witnessed the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which ended the Second Sudanese Civil War, and the eventual Referendum for Self-Determination, by which South Sudan gained its independence from Sudan in 2011.

Below, Allan Reed discusses the Addis Ababa Agreement of the First Sudanese Civil War, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of the Second Sudanese Civil War, and the 2011 Referendum on Self-Determination that followed six years after its signing.

Allan Reed’s interview was conducted by Carol Peasley on September 10, 2018.

Read Allan Reed’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Ashley Young.

Excerpts:

“What is needed is a Sudan people’s liberation movement, so that every Sudanese, whether African or Arab, Christian, Muslim, or with traditional beliefs, whether North or South, are all equal Sudanese citizens.”

Birth of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Second Sudanese Civil War: The Addis Ababa Peace Agreement gave political autonomy to South Sudan with its own government. Everything was fine for several years. It was a backwater. It probably would have just limped along that way, but then they discovered oil, and the oil was primarily in the South. President Gaafar Nimeiry said, “You have three provinces. We’re going to create 10 states, and we’ll carve out the oil, and it will be part of the North.” Of course, the Southern Sudanese said, “Well, we’re not saying the oil belongs only to the South, but those people in the oil area are Dinkas and Nuers, they’re not northerners. You can’t say that’s part of northern Sudan.” And they protested. So Nimeiry ripped up the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement, dissolved the regional government, established ten states instead of three states – divide and rule – and ultimately, by the spring of 1983, after Nimeiry had imposed Sharia law on Sudan, the former Anya-Nya units in the Sudanese army mutinied in Bor District in the South. This was in the spring, just as John and Rebecca Garang went down to Bor, where they are from, to cultivate their fields for the spring rains. The Sudanese army told John Garang “You know these ex-Anya-Nya folks. Put down this mutiny.” John Garang then went to the mutineers, and they told him, “We’ve bitten off more than we chew. You’re the one who should lead this movement.” Garang said, “I will do that only on one condition. We change the terms of the argument.”

The first war, fought for 17 years, was North versus South. The north is two-thirds of the country, two-thirds of the population. The Southerners fought to a stalemate. They didn’t win the independence they were fighting for, but they didn’t lose the war, and they were granted the regional government in the Addis Ababa Agreement. Garang asked, “What happened? President Nimeiry shredded the Addis Agreement when it served his own political purpose. Why should we do the same thing again? The argument is not North versus South. We should look at the country in terms of demographics. Two-thirds of Sudanese people are African. One-third 25 are so-called Arabs. If we are one-third of the population, where are the other half of us? They are the Africans in the north. The Nuba, the Funj, the Fur, the Beja in the Red Sea hills.” He said, “All of these groups are just as disenfranchised as Southern Sudanese. What is needed is a Sudan people’s liberation movement, so that every Sudanese, whether African or Arab, Christian, Muslim, or with traditional beliefs, whether North or South, are all equal Sudanese citizens.” He said, “If you’re willing to fight for a Sudan people’s liberation movement, that’s what I’ll lead.” Well, the Anya-Nya still believed, in their heart of hearts, in independence, but they swallowed hard and said, “Okay, if that’s what it takes.” And that’s how the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) was born.

“John Garang led the Comprehensive Peace Agreement negotiations, which were very complex, with a security protocol, a wealth-sharing protocol, a power-sharing protocol, the Three Areas protocol, and the Machakos protocol allowing for a Southern Sudanese Referendum on Self Determination.”

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement and Southern Sudanese Referendum:

Q: So it was to create a freer, better Sudan rather than to split the country? That was the intent originally?

REED: Yes, but the war [the Second Sudanese Civil War] then went on for 23 years, and it was brutal…. There was at least one to two million people who died in the first war, maybe more than that in the second war. The Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, ending the first civil war, was patched together very quickly. It did not address the fundamental issues between North and South – for example, it didn’t give the regional government any revenue generating authority – it only stopped the fighting. John Garang led the Comprehensive Peace Agreement negotiations, which were very complex, with a security protocol, a wealth-sharing protocol, a power-sharing protocol, the Three Areas protocol, and the Machakos protocol allowing for a Southern Sudanese Referendum on Self Determination, and it laid out everything that needed to be addressed…. I went back in 2010-1011 to support the Referendum on Self Determination….

“It’s six years because we want to give peace a chance. If we were to vote today, we all know which way we would vote.”

A Six-Year Wait:

Q: Again, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement called for there to be a referendum in six years?

REED: In six years…. In 2011. It was interesting. Before the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed. It was signed in January 2005. In 2004, after they had been negotiating for a little more than two years, all the complicated protocols that came together to be the CPA, John Garang went on a speaking tour to the liberated areas of South Sudan, and I went with him. We went to towns like Yei, Rumbek, Mundari, Padak. At each location he would explain for hours what all the protocols were that were being negotiated so that people would understand what they were working on. Then he answered every question that people had. These would take hours. I remember when we were in Rumbek, an old Dinka man asked Dr. John—they called him Dr. John—“Dr. John, you say that six years after the agreement is signed there will be a referendum on self-determination, and we can choose independence or remain united in Sudan.” He said, “That’s right. That’s the Machakos Protocol.” “Why do we have to wait six years to vote? I know how I want to vote now. Why can’t we vote now?” John Garang said, “Well, it’s six years because we want to give peace a chance. If we were to vote today, we all know which way we would vote. But if we give the North enough time for them to demonstrate they understand, it will be their responsibility to show us why unity is attractive. And if they do that well, then that’s an interesting choice. Maybe six years isn’t even long enough, but let’s give them six years.” The man said, “How do we know then? What should we look for?” In May 2004, John Garang said, “Watch what they do in Darfur. By that you will know where their heart is.”

(Omar al) Bashir was subsequently an indicted war criminal, there was genocide in Darfur, and John Garang was dead within a year. It was no wonder that when they voted, 98 percent of the people voted for independence. That was a genuine expression. He was prescient enough to say, “You’ll know where their heart is by what they do in Darfur.” What they did in Darfur was what they had done for two wars in South Sudan.

“They all voted for independence. Ninety-eight percent of the South Sudanese voted for independence.”

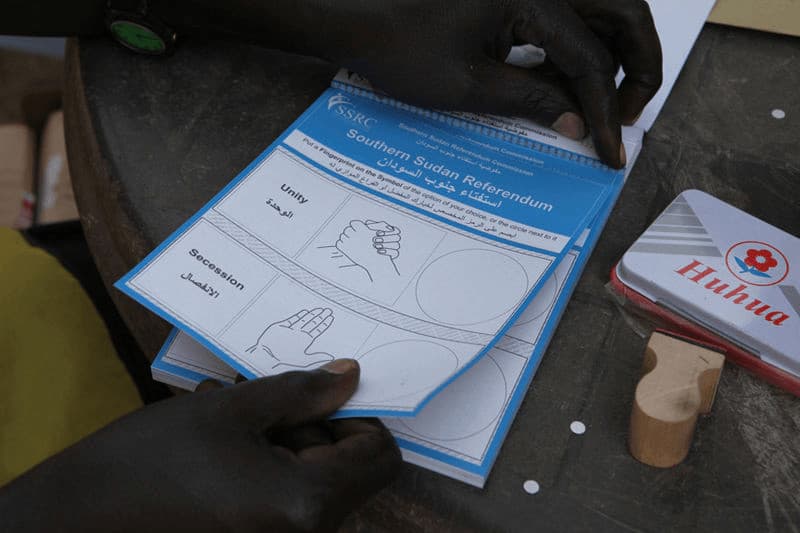

The Vote: When I was there in 2010 as the Southern Sudanese Referendum on Self Determination was due to come together as the final protocol in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, it was supposed to have been developed the year before, and Khartoum just dragged its heels. Nothing was being done. There was high anxiety…. I came to Washington and got an orientation to what was happening. When I got to Khartoum, while there was such panic in Washington about the situation, I found that USAID did have it together. There was still nervousness about whether the referendum was going to happen or not. The division of labor between USAID and the UN system was that one group would support the development of materials for the registration process, which had to go well, and the other group would develop the training for registrants who would man 4,000 sites, not just in Southern Sudan, but in northern Sudan, in America, and in Europe and Australia because the diaspora overseas could vote as well. They had to develop what the ballot would look like. So many people were illiterate, so a picture of clasped hands was a vote for unity, while “ma salama,” a picture of a hand waving goodbye, was a vote for independence. And then it was written in Arabic and English. Only Southern Sudanese could vote, but they had to develop a system of registration.

Q: So only Southern Sudanese? It was their decision what they wanted to do?

REED: Yes, even if they were Southerners in the north or in the diaspora. They had to develop a registrant’s card with the name, the date, the site, coding number and a thumbprint or signature, and it was embossed. This registration was done in November. Voting took place in January. They had to come back to the same places where they registered at the polling station. Sixty-five percent of those who registered would have to vote, otherwise it would not be considered legitimate. Sixty-five percent of those who registered had to come back to the same place 10 weeks later to vote. Sometimes it was a two-day walk from your village to the voting center. There was some question as to whether even that many would be able to do that. In the referendum itself, in early January, Kofi Annan was there as an observer. Jimmy Carter was there as an observer. The referendum was widely monitored internationally. As I mentioned earlier, I was in Malakal observing the governor of the state of Upper Nile cast the first vote, Simon Kun Puoch. He was my best 8th grade student in Gambela, Ethiopia, at the refugee hostel in 1968. I proudly watched the Governor cast his vote! In fact, Jeremiah Changjwok, the refugee student who, when he found out I was going to walk with the rebels in 1969 said, “Don’t go unless I go with you as your bodyguard.” I said, “Jeremiah, stay in Ethiopia and get an education.” He said, “No, you don’t know what you’re getting yourself into.” I probably owe my life to Jeremiah’s good counsel. He subsequently finished his education after we came out of the bush and he became the director of roads and bridges in Upper Nile. He voted in the referendum in Malakal, too. They all voted for independence. Ninety-eight percent of the South Sudanese voted for independence. Kofi Annan, Jimmy Carter, everybody in the European Union said it was free and fair election. When you see that number of people voting the same, you think of North Korea or someplace, but this was a genuine expression of public will.

Flying the Flag:

Q: Had there actually been campaigning? Was there anyone arguing for unity, or people really didn’t try to make that case?

REED: Some people in the national party from Khartoum, who were Southerners working in the South, actually said they would prefer to vote for independence. This, I think, was a very genuine expression of the public will…. When I left after the referendum, the Southern Sudanese gave me a big South Sudanese flag, which I flew on the balcony of our terrace in Sarajevo, Bosnia, when they voted…. When they got independence.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, University of California, Berkeley 1963–1965

MA in Public Administration, University of California, Irvine 1965–1967

Joined the Foreign Service-USAID 1977

Nouakchott, Mauritania—Program Officer 1978–1982

Conakry, Guinea—Deputy USAID Mission Director 1990–1992

Dakar, Senegal—Deputy USAID Mission Director 1997–2000

Lusaka, Zambia—USAID Mission Director 2000–2003

Khartoum, Sudan Field Office at REDSO/East Africa—Officer in Charge 2003–2005

Sarajevo, Bosnia—USAID Mission Director 2009–2012