Guns, cocaine, and kidnappings—this was the state of much of Colombia in the early 1980s. Medellín in particular, home to the rising Cartel de Medellín and leftist guerrilla insurgents, was the bedrock of anti-Americanism in the country during these years. Strikingly, Medellín was also home to a U.S. consulate at the time, hosting a total of four Foreign Service officers. Among them was Peter DeShazo, a public affairs officer and consul dedicated to improving the local perception of the United States and of Americans.

Amid the growing insecurity and tense environment, DeShazo’s goal was to retain a high profile as director of the U.S.-Colombian Bi-national Center (BNC). Kidnappings, murders, and violence were the norm in the epicenter of Colombia’s illegal narcotics trade. Yet surprisingly, the left-wing guerrillas were the main concern for Americans in Colombia; organizations such as the FARC and most notably M-19 posed the greatest security threat for DeShazo and his colleagues. Nonetheless, DeShazo confronted the rampant anti-American sentiment as the BNC gradually became a vital cultural institution in Medellín under his directorship. The center effectively disseminated U.S. culture through literature, film, and language programs as well as through visiting cultural attractions. After DeShazo left Colombia, the BNC continued to grow and ultimately became one of Latin America’s most successful centers, despite several attacks conducted by M-19 shortly after DeShazo’s departure. Once DeShazo’s tour in Medellín concluded, the Department of State decided that he would not be replaced as a result of the deteriorating security situation, essentially making Peter DeShazo the last U.S. diplomat in Medellín.

A graduate of Dartmouth College and the University of Wisconsin, DeShazo entered the Foreign Service in 1977 and spent much of his diplomatic career in Latin America. This included postings in Bolivia, Chile, Panama, and Venezuela in addition to his position as Public Affairs Officer and Consul in Medellín, Colombia from 1980-1983. DeShazo went on to be the Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs from 2003-2004 before retiring from the Foreign Service and working as the Director of the Americas Program for the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Peter DeShazo’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on August 14, 2013.

Read Peter DeShazo’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Alei Rizvi

Excerpts:

“Since me, there has been no U.S. diplomat stationed in Medellín.”

A Deteriorating Situation: At the time, I understood what the threats were and felt confident enough to be able to do my job quite freely. The largest threat to my security was probably from left-wing insurgents—guerrillas, especially the M-19 that had attacked the Medellín bi-national center more than once. When travelling outside Medellín, I was concerned about the FARC—the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—that was slowly taking control of rural areas in the Department of Antioquia—of which Medellín was the capital. Common crime was also a large concern. I was not as concerned about the drug cartels—at that point it did not make much sense for them to move against me—although they clearly could if they had wanted to.

To put this into perspective, when my tour in Medellín was about to end, the Department re-evaluated the presence of an American officer in Medellín and decided that the security situation was such that I should not be replaced.

The consulate was closed a year into my tour and the State Department officers were withdrawn. So I was there by myself for the last two years still with the diplomatic title of consul. And I ended up doing everything. I did political reporting, some economic reporting, reported on security, provided U.S. citizen services as needed, plus all the USIS stuff—running the bi-national center and the outreach to the newspapers in Medellín, relations with universities, the cultural community—all that.

“The murder rate in Medellín reached astronomical levels.”

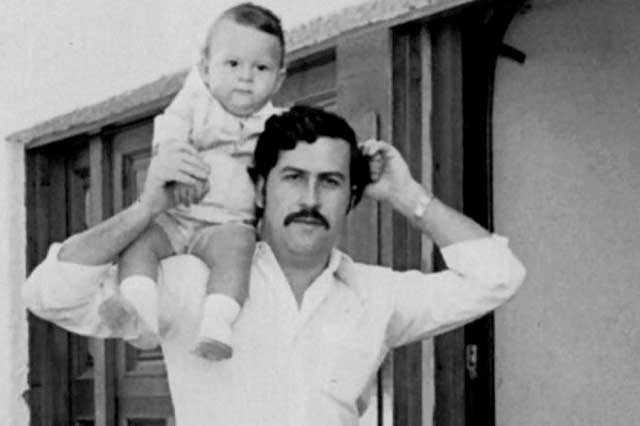

The Rise of Escobar: My three years in Medellín was a time in which the Medellín Cartel was really ramping up. They had pretensions of being a legitimate business concern but at the same time used any and all means, especially rampant violence. Drug-related killings were an everyday matter—

But at the same time, for example in 1982, Pablo Escobar, the leader of the Cartel, ran for the Colombian congress and was elected as an alternative representative out of Medellín. It was incredible that he sought to portray himself as a legitimate business and political figure—and also that he could be elected. I had no contact with any of the members of the Medellín Cartel, at least that I was aware of. It would have sent a terrible message.

In Medellín at the time, there was great concern about cartel money and influence penetrating legitimate institutions and organizations. Rumors about who was what were rampant.

“I did not think that my family was at risk – I would have been the target.”

Risky Business: I assumed that if someone wanted to eliminate me, they would find me somewhere other than at home. We had security at home and at the office, but the care that I exercised personally was also a key variable. I maintained both a low and a high profile—high on the cultural side as director of the bi-national center and low on the diplomatic side.

My greatest concern was the M-19 and the attraction that the bi-national center had as the key symbol of the United States in Medellín.

It became a place where a lot of people went, which was the goal. They studied English in large numbers and the BNC became a key cultural institution in the city. We had a good library, refurbished our art gallery and inaugurated a dynamic program in American film. USIA at the time was well-funded and many high-level U.S. cultural attractions visited under U.S. government auspices. I’m very proud to say that after I left, the BNC continued to expand in size, in the number of students, in its cultural presence, and became perhaps the most effective and dynamic bi-national center in all of Latin America. For me personally, running an institution with 60 employees and being responsible for generating its income, meeting payroll, covering administrative expenses and putting away a sizable reserve was a new and welcome challenge.

The M-19 attacked the BNC some years after I left, so it clearly had no qualms about striking against what it considered to be a U.S. presence.

“If somebody told me I couldn’t go someplace that’s where I wanted to go.”

Tackling Anti-Americanism: I did considerable programming at the universities, even the University of Antioquia, which was a center of support for the Left in Medellín and where anti-Americanism was the strongest.

When I heard “It’s a place where Americans don’t go and we never do anything there,” then my goal was to do something there. It was like catnip.

I remember doing a program there about the El Cerrejón mining project on the Atlantic Coast that was being developed with U.S. capital and we wanted to get our views across. If a group of people had a poor view of the United States, I wanted to do something about it.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

Dartmouth College 1965-1969

Study in Salamanca, Spain 1967

Student and researcher in Chile 1970-1971, 1974-1975

Joined the Foreign Service 1977

La Paz, Bolivia—Cultural Affairs Officer 1977-1980

Medellín, Colombia—Branch Public Affairs Officer and Consul 1980-1983

Santiago, Chile—Cultural Affairs Officer, First Secretary 1983-1987

Tel Aviv, Israel—Counselor for Public Affairs 1997-1999

Washington, D.C.—WHA Deputy Assistant Secretary 2003-2004

Retired from Foreign Service 2004