In 2000, the Clinton administration made the decision to release an undisrupted Global Positioning System (GPS) for civilian use. Since then, GPS has become an integral part of our commercial economy and everyday life. Hans Binnendijk, who served from 1999 to 2001

on the National Security Council, was involved in the decision making process.

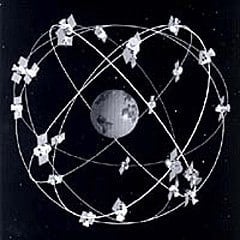

GPS was developed by the military for military use during the 60s and 70s. The system has its origins in the Space Race era, when U.S. scientists observed the Doppler effect created by Sputnik. The U.S. Navy launched its first experimental satellites in the mid 60s to track their nuclear submarines. The Department of Defense embraced the Navy’s program, and in the early 70s began developing a military-wide navigation system called NAVSTAR. The then-24 satellite system would be fully operational by 1993.

In 1983, President Reagan opened GPS (still in its experimental phase) to civilian use following the Korean Airlines Flight 007 disaster. However, starting in 1990, civilian GPS was purposefully degraded by the Department of Defense (DoD) for national security reasons. This was called “dithering.” The civilian version of GPS was intentionally kept much less accurate than its military counterpart to prevent adversaries from using it to attack the United States. By the time Hans Binnendijk was on the National Security Council, the government was realizing that the commercial and domestic value of an accurate civilian GPS was too great to ignore. In addition, the European Union was developing their own global navigation system that would compete with GPS. By 1998, DoD was seriously considering removing the restrictions on civilian GPS, but over a period of five years. Hans Binnendijk became convinced of GPS’s true civilian potential, and pushed for an acceleration of the timeline.

Binnendijk and the NSC played a role in encouraging DoD to find another method of security and ultimately providing greater accuracy to civilian GPS. In 2000, President Clinton signed a memorandum to remove the dither. GPS demonstrated its true military potential in Operation Desert Storm; the quick and decisive coalition victory could not have been achieved without GPS guidance. Today, GPS is still owned by the United States government and operated by the U.S. Air Force.

Hans Binnendijk’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on September 14th, 2009. Read Hans Binnendijk’s full interview HERE. Read another account of Hans Binnendijk’s career HERE.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Drafted by Merrill Rabinovsky

Excerpts:

“The concern was that our enemies would be able to use the civilian system and attach it to precision weapons and we’d lose the precision strike advantage we have”

BINNENDIJK: Another one that surprised me was GPS. You know we made some big decisions on. . . .

Q: These global positioning systems.

BINNENDIJK: Yeah, right.

Q: Which you could drive the car around and get great missile directions for as well.

BINNENDIJK: This was one of the things that happened on my watch that really made a difference. At that point we had two parallel systems: there was a military system that was highly accurate down to the size of a tennis court; and we had a system to be used by the public which intentionally had a dither put into it called selective availability and it was accurate down to the size of a football field. The concern was that our enemies would be able to use the civilian system and attach it to precision weapons and we’d lose the precision strike advantage we have. And yet we had this huge domestic industry that wanted to use GPS for cars and air navigation, sea navigation, and everything you now see. The plan was to retain the designed inaccuracy for at least another five years or so. We were able to change that and provide civilian GPS five years earlier than had been planned.

“American industry was quite eager to use this capability.”

Q: You say dither is—?

BINNENDIJK: That you build into the signal a mistake so that it is not as precise as it could be, again to protect your defense interests. American industry was quite eager to use this capability. So, one of the issues that landed on my desk when I was at the NSC was should we indeed continue with the existing time frame with this intentional inaccuracy built into the civilian system for at least another five years? Jim Schlesinger stopped by my office for a long conversation about all of this and after that conversation it became clear to me what the potential was in terms of transportation and everything else. So the issue was: can you protect your defense interest in another way? And so we asked the Defense Department to do a major review on that question: how else could we protect our defense interests? And the answer was you can regionally jam that system with a fairly small and simple device. So the military agreed to accelerate the accuracy of civilian GPS by about five years from the planned timeline. As a result of that, President Clinton signed a decision memorandum and we removed that intentional dither from the civilian system and the industry was able to step in very quickly and take full advantage of it. The other reason incidentally was that this move would provide better competition against the European Galileo system.

“. . . we’d rather have them spend their precious defense euros elsewhere.”

Q: The Galileo System being—?

BINNENDIJK: It is a European Union system.

Q: Developed separately from us?

BINNENDIJK: Yes, it was developed in the 1990s in large part because Europeans were asking “why do we have to rely on American technology for everything, and there’s money in it for European industry.” So they were basically going to develop a parallel system and they were going to charge people for it. The only reason it made any sense to do that was if somehow the American system was inadequate or had problems. We didn’t think it made any sense for the Europeans to do this because we’d rather have them spend their precious defense euros elsewhere. The commercial reason was by far the biggest, but a secondary reason was that if we could present the world with a very accurate system for, it really significantly reduced the logic behind the Galileo system. So out of that mix came a presidential decision to proceed with what we now know as a very accurate GPS system.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in History, University of Pennsylvania 1964(?)–1968

Ph.D. in International Relations, The Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy 1968–1972

Director, Institute for National Strategic Studies 1994–1999

National Security Council 1999–2001

Center for Technology and National Security Policy 2001–2009