Every American is familiar with the excitement and patriotism that sweeps across the nation on the Fourth of July. Many spend the day with family and friends, eating BBQ, and watching the fireworks explode in the night sky. Around the world, different peoples celebrate traditions for their own national holidays, which are shaped by unique cultures and histories.

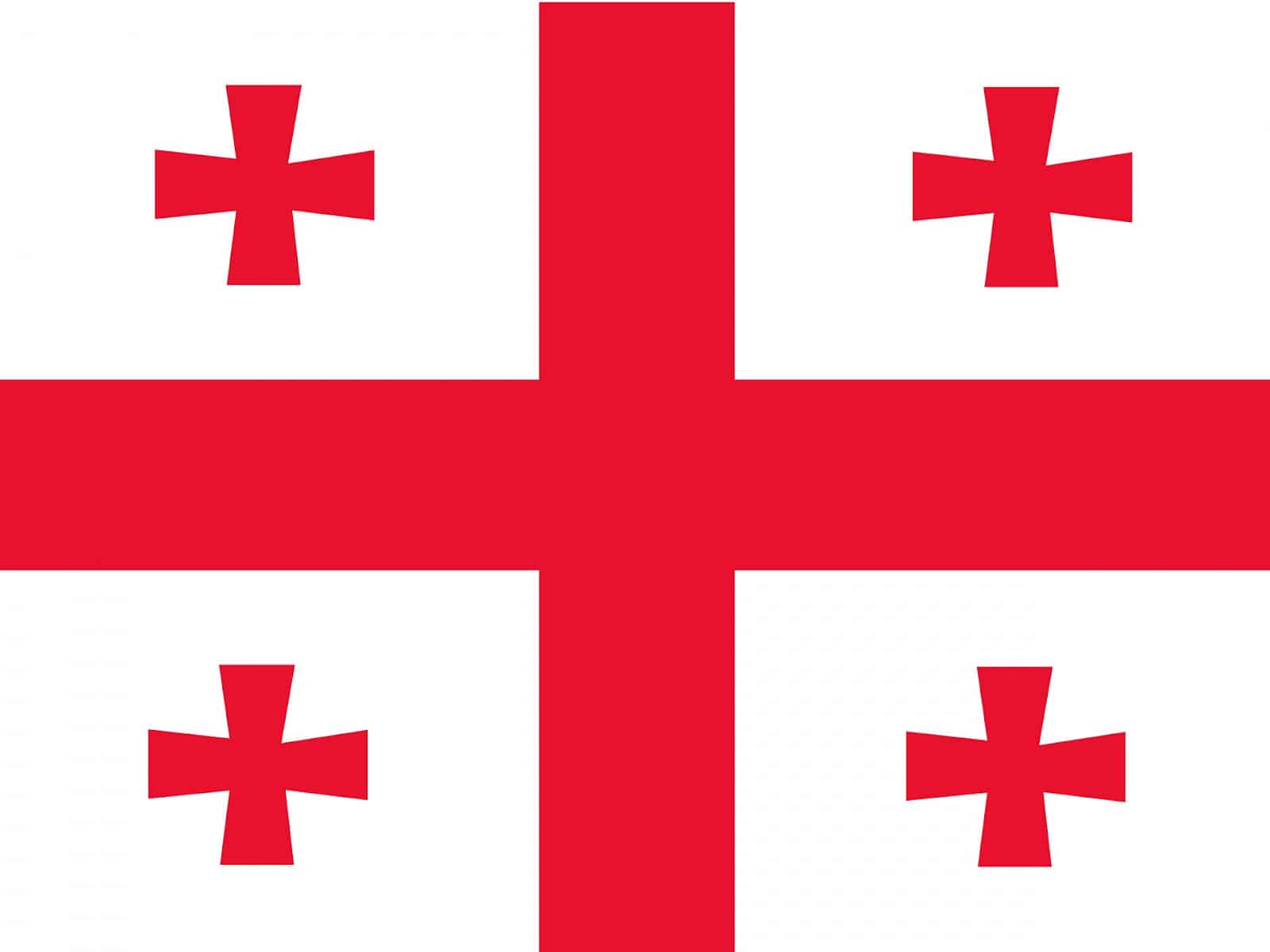

Georgia waited seventy years for its turn to celebrate its independence from the Soviet Union, and the patriotic festivities did not disappoint. However, declaring independence proved to be easier than actually living it. On May 26, 1918, following the chaos surrounding the 1917 Russian Revolution, Georgian government officials signed the Act of Independence, which declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of Georgia from the dying Russian Empire. Much to the Georgians’ dismay, this newfound freedom was short-lived. In early 1921, the Red Army invaded the country and annexed it into the Soviet Union. Under six decades of Soviet oppression, Georgians were unable to openly celebrate their independence until May 26, 1989, just a month after the infamous April 9 tragedy which left twenty-one Georgians dead at the hands of the Soviet government. Georgia officially seceded from the Soviet Union on April 9, 1991, just months before the final lowering of the Soviet hammer and sickle flag over the Kremlin on Christmas day.

Foreign Service Officer Constance Phlipot and her family coincidentally made a trip to Georgia. She was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Helsinki in 1987 as an Economic Officer, and often traveled to the Soviet Union to visit her husband, who worked just across the border at the U.S. Consulate in Leningrad. She was in Tbilisi on May 26, and witnessed the celebration first-hand. In this “moment” on U.S. diplomatic history, Phlipot describes the atmosphere of Georgia’s long awaited independence day celebration.

Constance Phlipot’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on February 5, 2016.

Read Phlipot’s full oral history HERE.

Read more about Georgia’s current internal ethnic conflicts HERE.

Read more about the Soviet Union’s final days HERE.

Drafted by Sophie May

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“And unbeknownst to us, it was the day of Georgian independence from 1918 and the first time that they were able to celebrate it.”

Party Crashers: In May of 1989 Doug’s [Phlipot’s husband] parents and his brother came to visit and we wanted to take them on a trip. We decided to go to Georgia. Now, in April of that year they had had a demonstration, they called it a massacre, quite a few people were killed and some people were in jail. We didn’t think we would get permission to travel, but we did. The embassy didn’t, but we were coming from the consulate, I guess the Soviets just saw this as, which it was, a family trip. And unbeknownst to us, it was the day of Georgian independence from 1918 and the first time that they were able to celebrate it. And I don’t know if you know, Georgians don’t celebrate things quietly, so everybody was out on the street in the main square or in their cars with the flags out the windows, and the whole place was just so alive. All the speeches in Georgian. We started to talk to some people next to us, in Russian, and asked if they could tell us what was going and they did. They then adopted us for the weekend. They took us out to dinner and they organized some outing to the ancient capital that was nearby, such a quintessential Georgian experience.

“I don’t remember what he said, except that it was a little crazy, and xenophobic, and anti-Muslim.”

Meeting a Future President: But we also took the opportunity to do a little political investigation there. Doug had run into a Leningrad opposition leader who happened to be on the plane on our way down. That actually is how we first heard that there was indeed going to be this celebration. The politicians said to us, “Well, you should call up Gamsakhurdia [first democratically elected Georgian president, 1991-1992 ],” the dissident who was under house arrest. Gamsakhurida’s father had been a famous poet, so the home was a “house museum” as the Russians call it and lovely, lovely surroundings. So, we talked to him a while and I don’t remember what he said, except that it was a little crazy, and xenophobic, and anti-Muslim. That was quite something. Gamsakhurdia who then became quite famous.

“A thing that struck us was how different it was from the rest of Russia.”

Expectations vs. Reality: No, Tbilisi was quite a place. A thing that struck us was how different it was from the rest of Russia. There were these sort of dry laws, anti-alcohol policies in the Soviet Union. But in Georgia you could buy alcohol anytime, anywhere. I learned later from some other people that had served in Moscow, how the Georgians would just completely flaunt laws. You know, create enterprises that only existed on paper in order to collect the inputs, but there was no enterprise to produce the products. It is kind of amazing that in the U.S. we always had the idea that the Soviets had a grip on everything and in fact they did not.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA Bowling Green University 1973–1977

MA in Science Policy, George Washington University 1977–1978

Joined the Foreign Service 1979

Helsinki, Finland—Economic Officer 1987–1990

Riga, Latvia—Economic Officer 1994–1997

Moscow, Russia—Deputy Economic Counselor 2000–2003

Minsk, Belarus—Deputy Chief of Mission 2004–2006