Is anything ever truly up to chance? Or are these moments of chance instead a culmination of one’s hard work? Possibly both? Regardless, these moments of chance—or rather, serendipity—are something with which former U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Counselor Kelly Kammerer is familiar. Throughout Kammerer’s career in the Foreign Service, he describes several notable moments of serendipity that substantially changed the trajectory of his life.

While it is possible that these moments were simply a result of Kammerer being in the right place at the right time, it is undeniable that his persistent work ethic and charisma were a large factor for why Kammerer received these opportunities.

Kammerer began his Foreign Service career as a Peace Corps volunteer in Colombia where he worked in the “most isolated and poorest” part of the country, Chocó State. Here Kammerer was primarily concerned with assisting the community to build infrastructure such as schools, teaching English at the public schools, and volunteering at the tuberculosis hospital. After two years, Kammerer went on to law school where he obtained his degree before joining the Peace Corps and then eventually applying for a position with the U.S. Department of State. Upon leaving this interview, Kammerer serendipitously ran into USAID Assistant General Counsel Denis Neil, an old college friend. In learning that Kammerer was looking for a job, he offered him a position.

After this chance encounter, Kammerer forgot about the State Department job and went to work for USAID, where he stayed for the remainder of his career. At USAID Kammerer focused on numerous pieces of legislation, most notably the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA)—or the so-called “New Directions” policy—which was designed to “promote the foreign policy, security, and general welfare of the United States by assisting peoples of the world in their efforts toward economic development and internal and external security” (U.S. Senate). In working on this act, which took a considerable amount of time, Kammerer experienced yet another moment of serendipity.

Early one Sunday morning Kammerer was working on the FAA on Capitol Hill when, “Mark Ball, who was the [USAID] general counsel at the time, showed up. He was on his way to church and had left something in his office . . . he came up to get it and there I was at 9:00 am on a Sunday working away.” This left such an impression on Ball that he then promoted Kammerer to deputy general counsel. In this new position Kammerer continued to work on legislative affairs. He later went overseas, serving in Nepal as mission director. Following the Nepal assignment, Kammerer returned back to USAID where, through another serendipitous moment, he was appointed to the position of counselor to USAID where he finished his career.

In this “moment” in U.S. diplomatic history, we see that overall, Kammerer had an extremely influential career as he travelled the world, focused on meaningful legislation, and formed meaningful relationships that he still maintains today. Kammerer’s hard work led to various serendipitous opportunities, which he parlayed into an enjoyable thirty-seven year career with USAID.

Kelly Kammerer’s interview was conducted by Alexander Shakow on December 16, 2016.

Read Kammerer’s full oral history HERE.

Read more about the Foregin Assistance Act HERE.

Drafted by Madeline Thompson

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“Life is full of them [serendipitous moments] if you examine it.”

Serendipity:

Q: Anyway, so let’s go back again to where you went to work for the Peace Corps and you were there for a couple of years.

Kammerer: I was there for five years … And this also proves my point about your life direction being affected by events you have no control over. I knew my five-year period with the Peace Corps was coming up and I looked at a few law firms and what not and I was then focusing on the Legal Advisor’s office of the State Department. I had an interview in the State Department and it went okay, I guess, I don’t recall, but as I was leaving the building I bumped into Denis Neill, who was an AID assistant general counsel at the time. He was a close friend of my roommate in Washington, Joe Sahid, who had also been my roommate in law school. Both of them served as lawyers in the Coast Guard when they first came to Washington, and I had gotten to know Denis pretty well through that connection. So, I bump into Dennis in the hallway and he asks what I was doing there? I told him I’d just had an interview in the Legal Advisor’s office. He said, “why don’t you come work for AID?” I said well, maybe … So, a few days later he organizes a lunch with Art Gardiner and Chuck Gladson, the general counsel and the deputy general counsel at the time. We had a nice lunch and they offer me a job on the spot, which never happens. There’s a hiring process in the general counsel’s office where you have to interview three different assistant general counsels and then it goes up the line and blah, blah, blah. So, that’s what happened. I got the job.

Q: That’s wonderful. So, if you hadn’t run into Denis no telling what would have happened.

Kammerer: Yes … Life is full of them [serendipitous moments] if you examine it.

“. . . . by the time I left if you were seen in the office of somebody of a different party you’d be in trouble with the other side.”

Political Polarization:

Q: Yes. So, you saw an enormous amount of change on the Hill…

Kammerer: When you and I were working on the authorization legislation in the late ’70s, the Congress was almost like a fraternity, between us and the staff and the members. Both sides were collegial and experienced. The members were very knowledgeable about the Foreign Assistance Act, about foreign aid, about foreign policy, and you’d have substantive discussions about legislation. You could talk to staff members from both parties at the same time. By the time I left you couldn’t. In fact, by the time I left if you were seen in the office of somebody of a different party you’d be in trouble with the other side.

Q: Now, when did this change?

Kammerer: It changed in the early ’80s. It wasn’t because of Reagan. It was more because of Newt Gingrich and a few others … I remember there was a Congressman from Pennsylvania named Bauman, who was a real bomb thrower. He started the period where there was so much animosity and you couldn’t trust the other side … everybody was so suspicious. These days almost nothing gets done in Congress, period. You don’t get any legislation on anything. You have continuing resolutions year after year after year. Maybe around the margins you can get this or that passed, but there are very few major legislative initiatives anymore.

“If that happens one time your reputation is shot forever.”

Trust on the Hill:

Kammerer: Most of what I was able to accomplish resulted from the relationships I developed over time with members and staff, particularly, after the demise of the power of the authorizing committees, with the members and staff of the foreign operations appropriations subcommittees. I’m probably the least likely person you can imagine as director of legislative affairs, but somehow, maybe because I started off in a legal capacity and I made contacts with people with whom I developed relationships of trust, I was able to work well with those committees when I became director of LEG. Trust is the most important attribute one needs when working with the Hill. You see lots of lobbyists who are smart, glib, but who really turn out to be a flash in the pan because they do something silly like grandstanding and busy Members and staff on the Hill conclude they can’t trust you. If that happens one time your reputation is shot forever.

Q: But how did you manage to- trust- but when you’re dealing with people like that you try to find ways to meet their needs …

Kammerer: I remember one time Skip Boyce, a very talented guy who went on to be ambassador to Indonesia and Thailand, but at the time was working for Undersecretary Schneider on Function budget issues, and he was asked by Undersecretary Schneider to be his liaison with the appropriation subcommittees. Skip came to see me because somebody in the State Department had said “we don’t know how the hell they do it but Legislative Affairs in AID manages to get things done so go talk to Kammerer down there and see what it is they do.” I remember telling Skip that there was really no big secret to it other than building trust, which I’ve already mentioned, but one thing I also told him I did was to make it a point to go up to the Hill and visit when I didn’t have to be there. When I didn’t want anything. Even though it’s a pain in the neck to get in a cab and go up to the Hill and wander around. But you have to be there at times when you’re not asking for anything, you don’t need anything, for them to get used to you and think of you as somebody will be there when they need you …

Q: So, if you were trying to suggest lessons for the legislative team in AID today what are the three things you would suggest to them since you’re not dealing with specific legislative issues but in terms of building this relationship?

Kammerer: It’s hard to say. It’s not a science. You have to be trusted so your word is your bond. You have to be willing to give and take. And you have to be able to leave your ego at the door. When something gets done, give credit where it is due. And always know your facts and the issues. Never be afraid to say you don’t know the answer to a question—it’s much better to say: “I’ll get back to you on that” than to try and wing it and maybe get it wrong. You also have to have the sense that you can share information. Not secrets, not giving away the store, but you have to be confident enough in yourself that you can tell the people that you’re dealing with what’s going on.

“Getting controversial legislation passed is so hard. Kennedy was lucky to have gotten it done in 1961.”

Foreign Assistance Act:

Q: … One thing I always identify with you is the monumental effort to examine the Foreign Assistance Act, reviewing each provision to determine who the author was, whether that person was still alive, all part of your effort to move towards a rewrite of the Foreign Assistance Act … When were you doing that? Late ’70s?

Kammerer: Yes –maybe 1977. That would have been when Dante Fascell was chairman of the committee. Key staffers Lou Gulick and George Ingram were talking with us about rewriting the entire Foreign Assistance Act. They said if you’re serious about this, it has to happen next year, and if we’re going to be taking up a bill to rewrite the Foreign Assistance Act we will need to have a complete legislative history of every provision of the FAA. The Committee will want to know whose ox is going to be gored if we propose changing or eliminating any provision. By that time the FAA had been around for over 15 years, and many of its provisions dated back to earlier legislation enacted after WWII. It was hundreds of pages long. I took on the job of compiling a complete, detailed legislative history of the FAA. I worked very hard at it for almost a year …

I had a few interns working with me but mostly I’d work weekends and nights on it. It’s the reason, in a very direct but unanticipated way, I was promoted to be Deputy General Counsel. This is another of these serendipity things. I was quite junior in the General Counsel’s office at the time, had only been there three years, and there were a number of senior lawyers around who were quite well thought of.

Then early one Sunday morning, it was around 9:00 am and I’d already been there for two hours working on this project, and Mark Ball, who was the General Counsel at the time, showed up. He was on his way to church and had left something in his office. So, he left his wife down in the car and he came up to get it and there I was at 9:00 am on a Sunday working away. And that made such an impression on him—hardly anyone in GC worked weekends, much less Sunday mornings—that when Eldon Greenberg suddenly left soon after as Deputy GC, because his wife died unexpectedly, Mark promoted over all these other people like Herb Morris, Judd Kessler and John Mullen, who’d been there, it seemed, forever.

I kept it [FAA] up to date for a few years because each year there’d be a few new provisions that changed the FAA, so you’d have to amend it and send out the updates. We distributed the two volumes around the world to our lawyers and other people, but as far as using it to help rewrite the Foreign Assistant Act, that never happened. There was an election, Reagan came in, and the project didn’t go anywhere. But the two-volume Legislative History is still around and still used by AID GC lawyers. We must have tried three or four times in my career at AID, most recently with Brian Atwood when I came back from Nepal in 1993, to rewrite the Foreign Assistance Act. Getting controversial legislation passed is so hard. Kennedy was lucky to have gotten it done in 1961.

“I remember getting to Nepal and asking, what can we show for having worked here over the last 40 years?”

Nepal Peace Corps:

Q: … So, why Nepal? I mean, was it just what opened up or—?

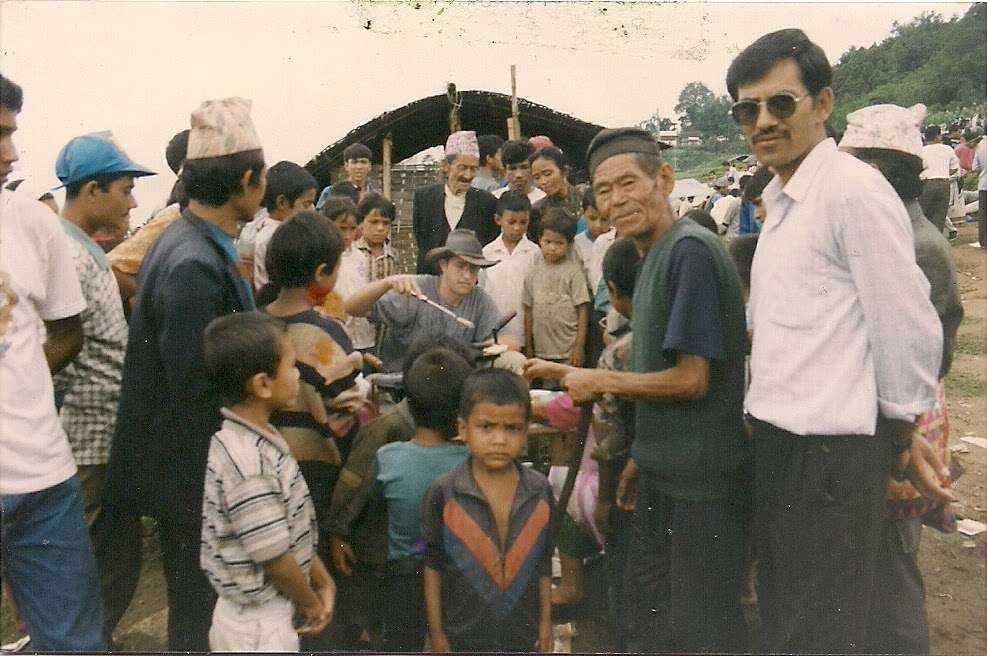

Kammerer: It was where I wanted to go and the Mission Director position was available. I didn’t want to go to a “political” program like Egypt or someplace where we were putting money in for political purposes. And that counselor back at Notre Dame my freshman year was right; I liked being outdoors. So, the idea of being in the mountains in a small development assistance program that was manageable, it had a $25 million a year budget, something like that, and nobody cared much about it, was very appealing. No political interest whatsoever, other than Senator Hatfield, who had put some money in an appropriations bill for some trees from Oregon … When I got to Nepal I discovered that one of my predecessors had decided that USAID should not be identified as the sponsor of any particular project, with the not unreasonable, at least to him, idea that everything should be credited to the government of Nepal. I remember getting to Nepal and asking, what can we show for having worked here over the last 40 years? What can you see that’s tangible? And it turned out it’s quite a lot; there was an awful lot. But nobody had ever really compiled a list. We built the airport and we built the ministry of health and we built this and that and the other thing. We made a map of Katmandu that put on it all of the things that AID had financed over the four decades that we’d been there and it was quite impressive. It was a good thing to have. I’d give that to visitors and say here, look at this, these are some of the things USAID has done over the past 40 years.

Q: … Were there any outstanding things that remain in your mind about that Nepal experience?

Kammerer: One of the first things that struck me was that Nepal was a favorite country for donors. Every conceivable donor in the world was in Kathmandu. We would go to the ministry of finance to see the minister and they had developed a system where they had the waiting room on one side of his office and an exit room on the other so that the donors wouldn’t be bumping into each other. Nigel Roberts, the World Bank representative, and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) representative, did a good job coordinating the donor community, but I often wished I was in charge of all of these donors so that we could combine all of our resources and make sure that we were focusing on the most effective thing. Nepal is an extreme example of that but I suppose donor coordination needs to be more effective everywhere because every donor has their own ax to grind and their own special areas of focus.

Q: … The focus of the program was what, agriculture for the most part?

Kammerer: Family planning, agriculture, rural development, yes … my role was to deal with the Embassy and Washington, to make sure that we got our budget and kept good relations with the people at the top. So, once I sorted out that I wasn’t supposed to be micromanaging the agriculture program or the health program, but I had good people that were doing that, and supported them, things worked smoothly.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA from Notre Dame University 1959–1963

JD from University of Virginia 1965–1968

Joined the USAID Foreign Service 1963

Chocó State, Colombia— Peace Corps 1963–1965

USAID — General Counsel 1975–1989

USAID—Nepal Mission Director 1989–1993

OECD Development Committee — U.S. Representative 1999–2003