During the 1990s, there were many international agreements created to limit nuclear weapons and the potential consequential effects of deploying these weapons. This began with the signing of the second Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START-2) in 1993, continued with the indefinite extension of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1995, and the creation of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996. Notwithstanding the views of major regional actors, Southeast Asia also reached an agreement to restrict the buildup of nuclear weapons in the region.

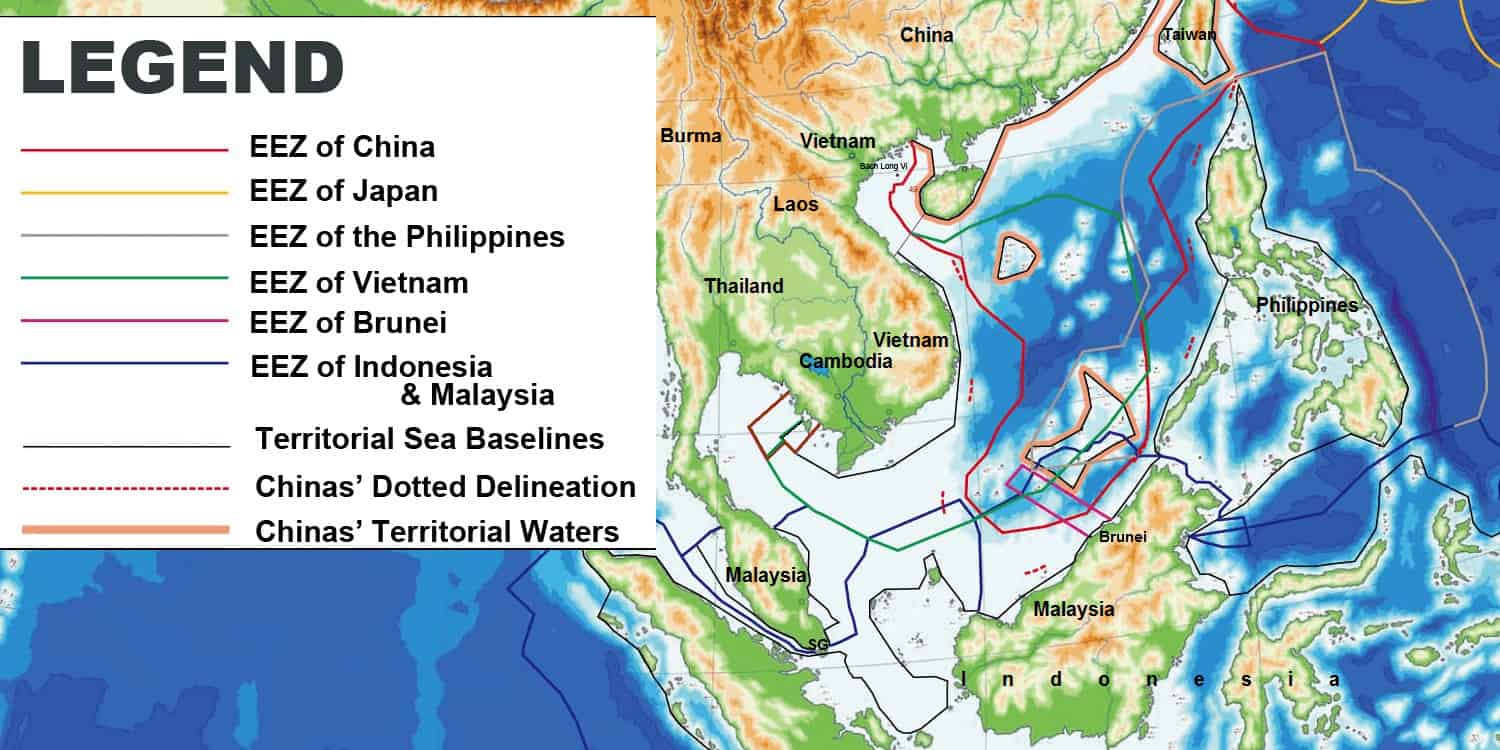

In 1996 and 1997, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) worked diligently to create a nuclear weapon-free zone. The issue was that these nations demanded that this zone be extended two hundred miles from land, which was to the outer limits of their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This would become known as the Treaty of Bangkok. The treaty, however, created issues for the two major powers in the region: China and the United States. China objected as this would interfere with their claims to the Spratly Islands and areas of the South China Sea. The U.S. Navy was unsatisfied as the treaty would mean that U.S. ships, submarines, and airplanes would have problems transiting the area with nuclear weapons on board. The other permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (P-5) also supported the United States on this matter in solidarity.

During this time, Ambassador Thomas Graham led a small delegation to Jakarta, Indonesia to join the P-5 for the purpose of presenting their issues regarding the Treaty of Bangkok. Ambassador Graham made an important presentation at the beginning of the formal meeting and had to deal with issues involving China.

In the end, Ambassador Graham was not able to change the minds of the ASEAN states. The Treaty of Bangkok entered into force in 1997 and established a nuclear-weapon-free zone for Southeast Asia and the members of ASEAN.

Thomas Graham’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on May 15, 2001.

Read Thomas Graham’s full oral history HERE.

Read more about Thomas Graham’s role in non-proliferation HERE.

Drafted by Nathaniel Schochet

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I promptly led them in a false direction.”

Problems getting there: In the fall of 1996 and into the spring of 1997, I tried to work out the differences over the Southeast Asian nuclear weapon free zone. I led a small delegation to Jakarta to join in a P-5 presentation to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the emerging treaty. We were going to have a meeting with the Chinese before the meeting with ASEAN. I was leading the U.S. delegation. I promptly led them in a false direction. While we were changing planes in Detroit (I thought Detroit was in the Central Time Zone) so I assumed we had an extra hour before our next flight to have a little discussion among ourselves. But Detroit is in the Eastern Time Zone. When we got back to the gate, there was our plane pulling away. It was Northwest Airlines. Highly perturbed, I said to the airline official that the gate, “We have a really important meeting in Jakarta. How are we going to get there now?” She said, “I can’t get you on this plane, but I will send you the other way.” We went on KLM, a partner airline, with a six-hour stop in Amsterdam and then we flew to Jakarta. We arrived three hours before our meeting with the Chinese. We were supposed to be there the day before. So we had just enough time to get to our hotel, change clothes and show up for the Chinese. But I guess all’s well that ends well, as they say.

“The U.S. Navy couldn’t live with that.”

Issues: Then we had our presentations to ASEAN. The issue was that the ASEAN nations insisted on extending their nuclear weapon free zone to the outer limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone, (the EEZ), 200 miles from land. This meant that U.S. ships and airplanes would have a problem transiting the area if they had nuclear weapons on board. The U.S. Navy couldn’t live with that. The Chinese, for their own geopolitical reasons, couldn’t live with that either because there are were lots of arguments going on about the Spratly Islands and who owns what parts of the ocean in Southeast Asia with their oil reserves and so on. So they supported us. The British, the French, and the Russians, for the sake of P-5 solidarity, supported us. They didn’t really care, but the Chinese did care.

“How can you negotiate with a country and reach a compromise if you don’t know what they want?”

Understanding historical perspectives: I opened the formal meeting with ASEAN with a long presentation. Then there was a break before the other four made their presentations. In the break I spoke with the deputy Singapore Ambassador, a woman in her 40s and said, “Why are the Chinese so difficult? Why do they never tell you what their position is? How can you negotiate with a country and reach a compromise if you don’t know what they want? Why won’t they tell us?” She said, “Two reasons—one is the Chinese tradition, “to find out anything, you have to travel to see the emperor or, in modern times, you have to go to Beijing; and the second reason is that they are very suspicious of the West and that is not going to change. The U.S. is the leader of the West and so they are going to be very suspicious of you. You might as well get used to it.” I said, “Do you mean because of the Korean war and Taiwan?” “Of course not, no; because of the Opium War and the Boxer Rebellion.” That was a memorable comment.

“It is known as the Treaty of Bangkok.”

Creation of Treaty: ASEAN never changed its position and at the end of 1997 they signed the treaty in Bangkok anyway. It is known as the Treaty of Bangkok. It establishes a nuclear weapon free zone for Southeast Asia—for all ASEAN countries. It retains the provision extending the nuclear free zone to the EEZ. I made four trips to the region to try to persuade them to change that provision. One of the trips was to Malaysia and the Philippines. The Philippines indicated flexibility but said Malaysia was the problem. I spoke with the acting Foreign Minister in Malaysia and he said, “We are not going to change our position. This is an anti-Chinese move and you can tell Washington that and we’re not going to change.” So they never did change and, as a result, none of the five nuclearweapon states supported the Southeast Asian nuclear weapon free zone by signing the relevant Protocol, unlike the free zones for Latin America, the South Pacific and Africa. Unfortunately the Senate has never ratified the Protocols to the Pelindaba Treaty (Africa) nor the Rarotonga Treaty (South Pacific)—even though the U.S. signed them almost 20 years ago.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University 1951–1955

The Institute of Political Science in Paris 1955-1956

JD, Harvard Law School 1958–1961

Started working for Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA) 1970

Washington, D.C.—Assistant General Counsel for Congressional Relation 1970-1974

Washington, D.C.— ACDA, Head of Public Affairs and Congressional Relations 1980–1983

Washington, D.C.— ACDA, General Counsel 1983–1993

Washington, D.C.— Special Assistant to the President for Arms Control Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, Ambassador 1994–1997