The end of the Cold War is sometimes thought about as a dramatic and rapid event marked by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the USSR. While these were notable moments at the end of the Cold War, the reality was much more complicated. Charles O’Mara’s stunning account of his time as trade negotiator for the U.S. government proves just how complex and intricate the end of the Cold War was.

The Cold War’s end occurred in an array of differing nations, which had different ramifications depending on the country and context. The decline of the Soviet Union did not come as a surprise to many, given that the massive military budget it had been running to compete with the United States was simply becoming unsustainable. Steady pressure on the Soviet Union by U.S. President Reagan, British Prime Minister Thatcher, and German Chancellor Kohl also contributed to the historical outcome: ending the Cold War with “a soft landing.”

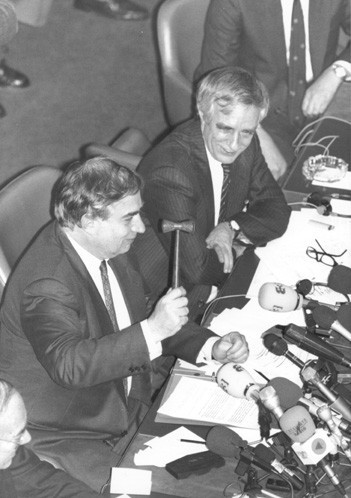

In this “Moment” in U.S. diplomatic history, we see that U.S. Foreign Service Officer Charles O’Mara had a long career in both the United States and abroad, with a focus on trade policy. O’Mara was pivotal in the negotiations leading to the Uruguay Round. While this trade deal had larger implications for the post-Cold War international order, the negotiations were much more complicated. While negotiating the Uruguay Round, O’Mara had to pay special attention to the specific agricultural interests of different states; he referenced this with a quote from a secretary: “suds and spuds . . .” (meaning potato and beer). O’Mara also encountered agricultural resistance from Japan, Australia, and New Zealand on an array of agricultural products with clashing interests. He negotiated around two of the three white commodities, sugar and dairy. Apart from his time in Washington, D.C., he served in Brazil, Argentina, and Switzerland. On his final return to D.C., he served as Under Secretary of Agriculture under President Clinton, ending a storied career in American trade policy.

Charles O’Mara’s interview was conducted December 8, 2017 by Allan Mustard.

Read O’Mara’s full interview HERE.

Drafted by Jordan Miner

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“The problems we had with Japan were enormous; of course, we couldn’t even export rice to Japan at that stage.”

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade: Well part of the problem in those days was the GATT rules with respect to what members of the GATT could do with respect to agriculture, particularly on import protection. The rules were not clear so it was relatively easy for a member those days to find ways to increase protection with quotas, particularly in the EU, and one of the areas where we had particular problems was oilseeds and in those days the EU market was our largest for soybeans. The problems we had with Japan were enormous; of course, we couldn’t even export rice to Japan at that stage. The other part of the issue was the use of export subsidies, which were completely free of any obligations under the GATT and in those days both the European Union and the United States, we had very very beneficial, let’s say, subsidies to produce particularly wheat and then with the excess supply the world market was basically governed by how much subsidies either the U.S. or the EU would apply to export primarily wheat but also other grains. It was a growing growing problem, plus we had in the late 1960s or early 1970s we had about 2½ times the world consumption of grains in CCC (Commodity Credit Corporation), just an example of how the domestic support was overwhelming frankly the ability at the time under U.S. law to, shall I say, manage the market in a much more reasonable way.

“The military probably, although I don’t know the exact number of people they murdered, but it was around 250,000 people.”

Argentina under military rule: Well, of course I was assigned there as the agricultural counselor. That time in Argentina was most tumultuous, to use that term. The military had taken over the government. It was the time of what was called the era of “desaparecidos,” which means disappeared in English. The military probably, although I don’t know the exact number of people they murdered, but it was around 250,000 people. It was just incredibly aggressive. Our two older children had to go to school with an armed guard because there was a very very very difficult, to use that term, relationship between the United States and Argentina at that time. The embassy functioned very well in the sense that we did communicate very well with each other, the staff and the ambassador. Many times, there were efforts to try to communicate more effectively with the military regime, but they didn’t want any communication. It was interesting too, the Archbishop of Buenos Aires at that time is now the current Pope Francis and he, I found out later, he worked very effectively behind the scenes to try to protect people from what the military regime was doing, most of whom were Catholics as it turned out.

“The role of the Uruguay Round and its effect economically was in many ways the first time that the objective of the United States and major European leaders had what was called to end the Cold War with a soft landing given the history we had with the USSR and the essential need to have a unified position between United States and European—well I should say the UK France Germany particularly.”

Soft landing of Cold War: The role of the Uruguay Round and its effect economically was in many ways the first time that the objective of the United States and major European leaders had what was called to end the Cold War with a soft landing given the history we had with the USSR and the essential need to have a unified position between United States and European—well I should say the UK France Germany particularly. This also signified how essential it was to resolve the differences we had in the Uruguay agriculture negotiation with our nine European Union partners and this is why the—I was asked or should say told to go to several summit meetings that took place among the leaders and it was it was amazingly how effective they communicated with each other even though there were political perspectives that were quite different. François Mitterrand was very much to the left for example. Margaret Thatcher much more to the right. President Bush was sort of in the middle. But it was amazing to go to these summit meetings because even though there is all the formality in the staff running around, saying, “Well, Mr. President, to your left is Chancellor Kohl, in the United States we would call him President,” you know that was standard procedure they never, none of those leaders needed to have any of that kind of help plus they never spoke with, him talking, they had agreed by telephone conversations several days before the summit meeting took place that these are the two or three issues we must resolve at this meeting and particularly as it related to the Uruguay Round and particularly as it relates to the agricultural provisions, so their summit meetings were very effective and even if they couldn’t agree to a particular solution at that meeting they did give instructions to me and to my European counterpart, Brussels’ counterpart, what we needed to focus on to get a solution.

“One is that Japan had no interest in finding a solution to the agriculture problems generally speaking because their Diet, their parliament, their Congress, at that time was totally controlled by ag interests..”

Japanese nationalism: There were two major sticking issues. One is that Japan had no interest in finding a solution to the agriculture problems generally speaking because their Diet, their parliament, their Congress, at that time was totally controlled by age interests and if the eleven prime ministers didn’t have effective relations with them he couldn’t get anything through the Diet that he wanted. And the other complication was that to make any significant international rules on the import protection that we were working on with the EU to get any effective rules in place, Japan had to fundamentally change their domestic support system from day one because all their almost all their trade restrictions had to use of term benefit of raising domestic prices substantially which benefited their farmers if those were reduced significantly then the Diet had to come up with a budget to support farmers, another huge political complication for them. But fortunately my counterpart, Hiro Shuwaku, he not only well understood the political complications he had domestically and he had me come to Tokyo—I don’t know how many times—so that I also understood that reality and whether I liked it or not I had to accept it if we were to find a solution and that was one of the reasons why we on domestic support rules separated the Green Box from the domestic support that was subject to strict rules.

“I mean we had on the European side it was the French that were the most determined to continue the status quo even though Germany wanted to change England wanted to change but France wanted absolutely no change.”

French desire for status quo: And that also happened on the EU side and that’s what happened in Tokyo too. I mean we had on the European side it was the French that were the most determined to continue the status quo even though Germany wanted to change England wanted to change but France wanted absolutely no change. And fortunately with Guy Legras not only did I understand how significant the political influence in those days was in France, it was also the pathway that we eventually found to have a Green Box so there would be some way to provide funding to producers as long as it wasn’t crop related so one of the most interesting lessons certainly in my experience was really understanding how significant political complications were for my counterparts and I really appreciate all they did to make sure it wasn’t just them telling me what the political reality was for them. They wanted me to see it firsthand. They wanted me to talk to the producers, which I did in Japan and I did in Brussels and it was the basis then for what we were able to develop as the solution and a final agreement.

“It was in one word very difficult. I think it was also a very significant learning experience for me,”

Department of Agriculture: It was in one word very difficult. I think it was also a very significant learning experience for me, you know, comparing Secretary Espy, his background and experience when he came to be secretary and say Dick Lyng, when he became secretary. Dick Lyng had a very active role in California agriculture before he became secretary. Mike Espy really didn’t. I mean he certainly understood the cotton pressure and so forth. I think one of the biggest consequences too with Secretary Espy was that he had his Chief of Staff who was with him on the Hill at the Department and that was a huge difficulty in many respects because being a Chief of Staff when you’re a member of Congress and being a chief of staff when you’re head of a department with how many thousands of employees all over the United States and in some cases all around the world it’s a totally different world and I think Mike I think it was an effective way for me to convince Mike that he really had to understand the significance of the broad powers that he had and it wasn’t just you know sitting in the secretary’s office and making X, Y, or Z decision. If you don’t have the support, understanding of the bureaucracy any of those decisions may never be implemented effectively. He learned that.

“NAFTA that we had in fact a legitimate free-trade agreement with Mexico even though the sugar people did wind up finding a way to get Congress to impose some quotas a…”

Sugar lobbyists: Well, the major change was international rules that govern how trade would take place and international rules that govern how domestic support would be implemented and you know prior to that you know it was how much money we would use to fund PL 480 or export subsidies where they existed. That all changed with the Uruguay Round agreement and even though we had some complications obviously with the implementation of NAFTA that we had in fact a legitimate free-trade agreement with Mexico even though the sugar people did wind up finding a way to get Congress to impose some quotas and even though we had problems with dairy and wheat, the Canadian Wheat Board is now gone, and I think those all those speak to how important it is that in today’s very interconnected world and to cut back quickly to the Uruguay Round and American leadership President Bush European leaders recognizing the geopolitical significance of an effective Uruguay Round agreement. That was the recognition of all that’s a recognition of what we have in today’s world. We have a totally interconnected world whether it’s supported or it’s not, but that is the reality and it you know the Uruguay Round is a good example of if we don’t have international rules that govern how in the case of agriculture with this trade policy or domestic policy it becomes a battle between you and me or Country X and Country Y that that doesn’t advance economic interest of Country X or Y.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA, University of Maryland 1961–1965

Joined the Foreign Service 1966

Buenos Aires, Argentina—Attaché, Agriculture Counselor 1977–1985

Geneva, Switzerland—USTR, Special Trade Representative 1989–1990