In early August 1990, the president of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, ordered the invasion of Kuwait. Some of Hussein’s contentious justifications ranged from accusing Kuwait of stealing crude oil from Iraqi territory to the idea that Kuwait was an artificial state originally a part of Iraq carved out by western powers. In the eyes of many countries, this reasoning did not justify Iraq’s actions; in addition, Iraq’s failure to adhere to the UN Security Council’s resolution calling for its withdrawal from Kuwait resulted in NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] allies, as well as several Arab nations, conducting Operation Desert Storm and the beginning of the Gulf War. Nearly a year after Iraq invaded Kuwait, Iraqi forces were pushed out and forced to retreat on February 28, 1991. President Bush then declared a ceasefire.

Colin Powell remained deeply involved throughout the Gulf War conflict as he was serving as the Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff. During this time, he developed the Powell Doctrine, which was based upon the U.S. experience in Vietnam. It stated that if the United States goes to war, it needs to have a clear military objective. The Doctrine’s purpose is to ensure an appropriate amount of troops are deployed, the military has popular public support, and that it has an exit strategy. This was to ensure that the function of troops would be solely focused on military operations rather than non-military activities, like building schools.

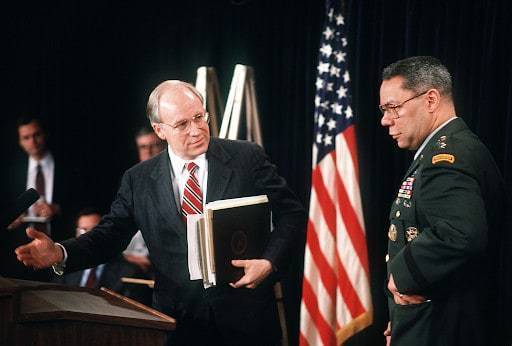

This “moment” in U.S. diplomatic history examines the situation from the perspective of Ambassador Arthur R. Hughes, a career foreign service officer who had taken an assignment in the Office of Secretary of Defense as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for Near East and South Asia. Hughes recalls a conversation between Powell and then Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney regarding transmitting information to President Bush, highlighting the tension in the administration. There was a conscious effort to avoid repeating the same mistakes made by the military in Vietnam. Hughes remembers, moreover, another conversation he had with Colin Powell and Ambassador Skip Gnehm about the disagreement on removal of troops from Kuwait. The three ended up having a very lively conversation and Ambassador Hughes’ argument “became the policy.”

When Ambassador Hughes transitioned out of the Defense Department, Colin Powell stopped him and said, “Well, Art, we always didn’t see eye to eye on things, but we got some things done anyway, didn’t we?” Even though Colin Powell may not have agreed with everyone he worked with, he made sure to put these differences aside and work with people to achieve the best outcome—which earned him great respect from those he worked with.

To learn more about Colin Powell click here.

To learn more about Ambassador Arthur H. Hughes click here.

To learn more about the Powell Doctrine click here.

To learn more about the Gulf War click here.

Drafted by Nathaniel Schochet

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“And Powell sat back and said, “Yes, sir, Mr. Secretary,” and that ended the meeting.”

Q: This was seen as a great victory, and why prolong where there would be chances of losses?

HUGHES: Well, there was this fact too quite frankly, and I saw it up close even at the very beginning, the next day after, on August 2nd. Secretary Cheney never served in the military. He had a series of student deferments. I think that plus the fact of who Colin Powell was, who Cheney selected to be Chairman—recommended to the President, that is, to be Chairman—meant for a great amount of care and work on making sure that the relationship was a positive one that worked and that was a collegial one. But I can remember that first meeting on August 2nd when Cheney called in Powell, Wolfowitz, and Wolfowitz took me along, and there must have been about six or eight people in his office. He said, “Okay, where are we? What do we know?” And he kept asking Colin Powell, “What are our military options?” and Colin Powell kept saying—this was all a very free-flowing, informal conversation—”Tell us what you want to do, and we’ll see if we can do it.” Cheney said, “What are our options? We owe it to the President to tell him what the options are.” And Powell said, “No, you tell us what you want to deal with,” and finally Cheney said, “Look, I need to have those options, and would you please give me those options?” And Powell sat back and said, “Yes, sir, Mr. Secretary,” and that ended the meeting. That was the first time in that meeting that he said, “Yes, sir,” or “Mr. Secretary.” Before that, it was all very informal. I mean it wasn’t a Colin and Dick kind of thing, but it was, “Yes, sir, Mr. Secretary.” This has got to be seen in the historical context, too, of Vietnam and all the things that had happened and the fear of the military being pushed out ahead and then look behind them and no politicians are back behind them. That’s all understandable, so I’m not making a judgment here, I’m just saying that’s what happened.

At the end, to come back to your question, everything was happening very, very fast. I think JCS wanted to do certain things. They surprised Schwarzkopf. I think when they went to Cheney, my judgment is that he was probably a little surprised. The guys, the commanders on the ground, were surprised. I also had a very interesting, very lively meeting with Colin Powell when I heard that he wanted to try to get the troops out of Kuwait just as soon as possible. Skip Gnehm, who was the ambassador without a country, was in town, and I called and I said, “Skip, we’ve got to go see Colin Powell. I don’t think I can do this alone. I’ve got to have you there too. I think maybe we can do it together.” So Skip and I went to see Colin Powell. We said, “Mr. Chairman, this is absolutely wrong. This is absolutely wrong. We’ll talk about the political aspect. We’ll suggest it also is wrong militarily. You can ask your own guys. We can’t pretend to give you advice on the military side, but politically it’s absolutely wrong.” And we let out hammer and tongs. In fact, Powell’s military assistant, who was a colonel and to the general officer, said, “I’ve never sat in a meeting like that with the Chairman.” As it turned out, I think the fact that Skip and the Ambassador were there was key, was absolutely critical. Colin would have listened to me, but you know. As it turned out, what we were trying to do became the policy, the schedule. When I went to go see Colin when I left the Defense Department, the first thing he said was, “Well, Art, we always didn’t see eye to eye on things, but we got some things done anyway, didn’t we?

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Entered Foreign Service 1965

The Hague, The Netherlands—Deputy Chief of Mission 1983–1986

Defense Department—International Security Agency [ISA] 1989–1991

Yemen—Ambassador 1991–1994