In 1938, in the shadow of the Great Depression came rumblings from Europe of a great war and with it the open hatred and extinction of several groups, most famously Jews. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his administration remained largely focused on recovering from the Depression and desired to remain uninvolved in the chaos in Europe. This, unfortunately, led to heavily restricted immigration and the State Department’s refusal of tens of thousands of Jewish refugees. However, there were dozens of brave consular officers who chose to defy regulations and save the lives of Jewish refugees by granting them visas and entry into the United States.

In 1917, the first nationwide legislation restricting immigration passed. This early form of immigration regulation introduced a literacy test that prospective immigrants were required to pass, as a way to ensure that only “skilled” workers were being brought into the United States. In the early 1920s, Congress felt that more restrictive immigration laws were needed, and introduced a quota system. The 1924 Johnson Reed Act defined a quota system with lower quotas, using census data from 1890 for calculating these quotas. European immigrants were not the sole targets of this legislation as the act also targeted Asian immigrants, specifically Japanese.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Breckenridge Long began advocating for even more restrictive immigration laws and lower quotas. A common fear across the nation was that immigrants fleeing the violence and impending war in Europe would burden the system and take jobs from Americans struggling to feed their families and recover financially. Long was well known to harbor hatred for Jews, having written appalling slurs in his diary regularly and sharing his opinions with his subordinates—many of whom shared his views.

As the war in Europe erupted in 1940, concerns of espionage mounted. FDR and Long shared concerns that some amongst the tens of thousands of refugees from Europe coming into the United States could be Nazi spies sent by the German government. This paranoia gave Long leeway to introduce several more restrictions on immigration from Europe, aimed at reducing the number of Jews entering the country. These secret policies forced consular officers to cut the number of visas given almost in half. One of the policies put in place was called the “relative rule”—a policy which meant that a refugee seeking entry into the U.S. who had any relatives still living in Nazi occupied territory would be automatically denied entry. In 1940, days after France surrendered to the Nazis, Long circulated a now infamous memorandum to all his State Department colleagues in which he outlined a plan to completely shut down immigration during times of national crisis. In this memo he advocated for consular officers to “put every obstacle in the way, require additional evidence, and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas.” Luckily, Long’s memo was never put into effect. The restrictive set of immigration policies remained in place well into the Second World War, until pressure from Jewish members of the federal government mounted enough of a response to force Congress and President Roosevelt to investigate and reconsider these rules.

Perhaps the most visible example of the devastating effects of American immigration policy towards Jewish refugees is the turning away of the M.S. St. Louis in 1939. On May 13, 1939 the St. Louis sailed from Germany towards the United States with plans to dock in Cuba to await the processing of U.S. visa applications for the over 930 Jewish passengers on board fleeing persecution. The majority of refugees on board had already applied for visas to enter the United States and were hoping they would be welcomed upon docking in Miami. After being turned away in Cuba, the ship was not even given permission to dock in Miami. An attempt to contact President Roosevelt was made, but his office never responded, and a State Department telegram stated that the refugees had to return to their countries of origin to wait for their visa applications to be processed. Over one third of the passengers on board the St. Louis that day would later be killed in the Holocaust.

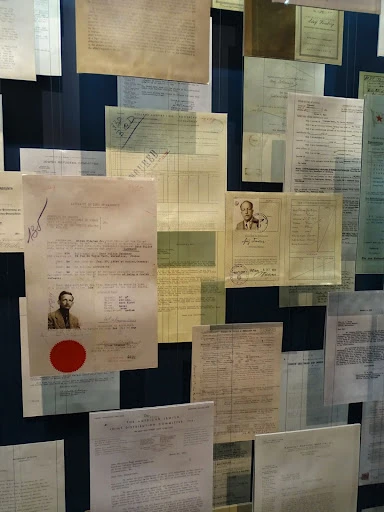

There were, of course, still those who actively resisted these policies. Consulates were flooded with tens of thousands of Jewish refugees attempting to escape the raging anti-Semitism spreading through Europe. The legal system of quotas and visa applications could not withstand the mass amounts of people seeking refuge, so visas were given more leniently than before since Foreign Service Officers knew that the rise of Nazi power was approaching—and fast. Stretching the visa laws and regulations became the new norm, and different procedures (i.e. literacy tests, familial ties with a citizen within the country, country of origin quotas) that normally stood no longer took effect.

One notable example of consular officers disregarding quotas is at the U.S. Embassy in Paris in 1939 and 1940. Consular Officer William Trimble spoke about bending regulations, “… we twisted regulations. We really twisted regulations, and we got an awful lot of people out. And I’m sure it was done in other posts, too. Then war was declared.” In dozens of consulates all around the world, there would be a relaxation of visa application regulations for the especially large influx of refugees, where Foreign Service Officers attempted to funnel as many refugees as possible to safety, stretching quotas to the fullest possible extent. History shows that, unfortunately, many were still turned away.

Drafted by Sophia Reitich and Shae Bianchi

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

AMBASSADOR WILLIAM C. TRIMBLE

Paris, France—Consular Officer 1939–1940

“Immigration law was bent. Regulations were bent.”

Bending the Rules in Paris:

TRIMBLE: Because of my work in graduate school, the courses there in economics and finance, I was transferred to Paris.

Q: This was in 1939.

TRIMBLE: We arrived four weeks before war broke out.

Q: As I say, it’s a vintage 1939.

TRIMBLE: Yes, it was. My wife and I went over leaving the children. We were hoping to get an apartment somewhere in Paris. Of course, they never got there.

I was meant to be working on financial matters, but then when I got there, there was such a rush of people—immigrants, refugees, the German Jewish refugees wanting to get into the United States—that I was put on the visa desk, as were several other officers. And we did that until war was declared.

Q: Could I ask you a question? Because this is really a very crucial part of American policy in this period. What was our attitude? I mean, you know, there you were on the visa desk, and you had people trying to get out, particularly the Jews. And, of course, we know now what was waiting for those that didn’t get out and that was the gas ovens for many.

TRIMBLE: We didn’t know that.

Q: We didn’t know then?

TRIMBLE: No.

Q: And it’s been claimed that the State Department was indifferent and all. What was your feeling? And what were your instructions at that time in dealing with that situation?

TRIMBLE: Well, we knew about Kristallnacht and having served in Europe.

Q: Kristallnacht being—would you explain what it was?

TRIMBLE: Kristallnacht was when Hitler’s Brownshirts attacked and burnt synagogues and broke the windows of Jewish stores in Germany. And that was the beginning, really, of the persecution of the Jews and the Jewish population in Germany. Many of them had gotten out mainly to France, but most of them remained in Germany. Our job was to do everything we could to help them get out. Immigration law was bent. Regulations were bent. For example, there used to be a provision of the law that said that skilled agriculturists had a preference. Jewish groups in this country formed a school in Paris where in three months refugees studied agriculture. Well, that school was a subterfuge and we knew it. But we overlooked that. There was also an institution called the New School For Scientific Research in New York, and people would come to join it. I gave so many visas to so-called “professors” that I’m sure the number of people on the staff of the New School For Research was far greater than the number of students. Yes, we leaned over backwards. Indeed I was criticized several times by the Immigration Service for being overly lenient. And the rest of us were doing it, too. We were doing everything we could to get the refugees out.

Q: I come from a basic consular background, and often you get people at the top who get very consistent on the regulations within an embassy, but down below the vice consuls who are dealing with the problem, see what the problem is and do everything they can to help.

TRIMBLE: Yes.

Q: How about in the Embassy? Were you getting any sort of pressure from above, say, “What are you doing?” Or even from Washington?

TRIMBLE: Well, the Ambassador, Mr. Bullitt, William Bullitt, was very much in favor with what we were doing. Actually, he had Jewish blood, but that had nothing to do with it. But he believed strongly in what we were trying to do. He gave us all the support he could. Washington wouldn’t tell us directly. But, yes, it was unwritten that you do all you can.

Q: You had that feeling?

TRIMBLE: And we twisted regulations. We really twisted regulations, and we got an awful lot of people out. And I’m sure it was done in other posts, too. Then war was declared.

Q: This was September 1, 1939.

Read more from William Trimble’s Oral History HERE.

AMBASSADOR DOUGLAS MACARTHUR, II

Paris, France—Consular Officer 1937–1942

“In retrospect, we perhaps were too strict, but we stretched the immigration law that the Congress had passed to the maximum extent possible, I think.”

Surpassing the Quota:

Q: Were there any instructions on how you were to deal with this?…The Foreign Service and the State Department has been criticized, particularly after the war and after the extent of the Holocaust was known, for their…strict adherence to the immigration.

MACARTHUR: All of us in those days, when you entered the Foreign Service, you entered as a probationary vice consul after you passed your oral and written examinations.

Your first assignment was invariably at a consulate general where you did visa work, commercial work, shipping, protection work, citizenship, and the like. We were under very formal training and instructions at that time about the requirements that were required of people who were applicants for visas. But in retrospect, we perhaps were too strict, but we stretched the immigration law that the Congress had passed to the maximum extent possible, I think. We encouraged these people if they had friends or relatives in the United States who would undertake to see that they didn’t become a public charge to fulfill that requirement, and so forth. The public charge requirement, I think, was the most difficult problem. The rest of the thing, there was a relaxation on temporary visas for refugees…The basic requirement was that they show that they would not arrive in the United States and become a public charge.

Read more from Douglas MacArthur II’s Oral History HERE.

WILLIAM BELTON

Havana, Cuba—Visa Officer 1938

“I never felt there was anything but sympathy for this tremendous problem and the people involved in it.”

Sitting on Benches in Cuba

BELTON: Havana was flooded with European refugees. This was just before the outbreak of the war. The city was just full of German Jews who had been unable to get U.S. visas while they were still in Europe, so had come to Havana to wait until their numbers came up on the quota system for the United States. So we had a really big and extremely active, busy visa mill going there. That was my principal duty… I never felt there was anything but sympathy for this tremendous problem and the people involved in it. There was a difference between our attitude toward these people, how we handled them, and what the laws enabled us to do for them. Thousands of people were eventually going to get into the United States, one way or another. We knew that. It was a tragedy that we had to keep them sitting there on the benches in the parks of Havana for years on end sometimes, before they could come. When they walked into the office, we did the very best we could under extremely difficult circumstances. Understandably, the visa applicants themselves weren’t always models of patience.

I remember on one occasion we received a complaint from the United States about how somebody was treated at the reception desk. The Consul General, Coert du Bois, was a very imaginative and gung-ho officer. When he got this complaint he had a photographer come and take a picture of the receptionist at work.

It was a very dramatic picture. There was this young woman at her desk surrounded by at least twenty people, all with their arms out, shouting at her, trying to get her attention, trying to get in. The poor woman was trying to cope with this great crowd of people.

I honestly don’t feel that there was anything untoward about the way we handled the people in general under the circumstances that existed at the time, which were extremely difficult for everybody, on our side and theirs as well…

The people were swarming into Cuba, not only from Germany but from many other countries. We had people from thirty or forty nations, it seemed, all lined up there waiting for their visas. As far as I can recall, Cuba was a very hospitable place for them. It was comfortable, warm; of course they had to have some means and I am sure a lot of them were in difficult economic circumstances, but I don’t think the Cubans were giving them any particular problem.

Read more from William Belton’s Oral History HERE.