In 1978, the Carter administration passed the Airline Deregulation Act, which deregulated the airline industry, stripping away federal control of a number of important functions such as creating new airlines, setting airfares, and establishing new routes. Before this act, the federal government’s Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) regulated the routes of airlines that flew internationally and state governments regulated airlines that flew only intrastate. Additionally, the CAB could regulate ticket prices. It could lower them for short haul flights or raise them for long haul flights. CAB did what it thought was best for promoting air travel. However, the bureaucratic nature of the CAB contributed to delays in airlines getting approvals for requests such as changing or adding routes.

While this system seemed to work decently for a number of years, the 1973 oil crisis and stagflation pushed it to the limit. Big airlines benefited from the fixed federal prices and stagflation. However, consumers, economists, and the Carter administration were pushing for the deregulation of air travel. The administration was concerned that if the industry remained regulated, it would decrease so drastically in popularity that it would go bankrupt like some of the biggest railroads did just a few years prior.

By 1978, the Act was passed. Airlines were now in control of adding and changing their routes and fares. New competition was also brought into the market, challenging some of the older airlines who once held a monopoly in the industry. Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) was one of these old airlines with a strong grip on the international flight market. Pan Am was at its peak from the late 1950s to the early ‘70s. However, the Deregulation Act of 1978 brought about its slow downfall, causing the airline to declare bankruptcy in 1991.

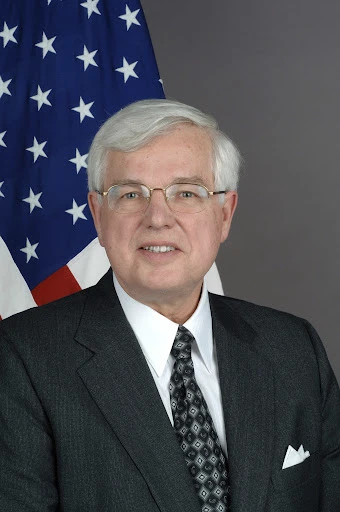

Donald Bliss witnessed firsthand many of the changes brought about by deregulation of the airline industry. With experience in government affairs, transportation, and aviation, Bliss reached the rank of a U.S. ambassador by the end of his career journey. In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic in History,” Bliss provides insight into the effects of deregulation. In 1978 he was representing Pan American while working in the private sector at O’Melveny & Myers. His prior experiences at organizations such as the Department of Health, Department of Transportation, USAID, and American Bar Association informed his views. As he neared the end of his career, he served as the permanent representative of the United States to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

Donald Bliss’ interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on November 21, 2013.

Read Donald Bliss’ full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Kaitlyn Flynn

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“What happened was airline deregulation. Through his political connections, PanAm’s founder Juan Tripp created a U.S. monopoly on most international routes.”

Monopoly and Deregulation:

Q: When did you start representing Pan Am?

BLISS: We handled the first merger after airline deregulation in 1979, Pan Am’s acquisition of National Airlines. The purpose of the merger was to enable Pan Am to develop a domestic system that would feed its international routes in competition with United and American airlines which were initiating competitive international service.

Implementation of the merger, however, proved difficult because the airline cultures were so different.

Q: Could you talk a bit about the culture as you saw it at Pan Am? Because we’re talking about—at one point this was the bright and shining star of American aviation. And something happened. What—

BLISS: What happened was airline deregulation. Through his political connections, Pan Am’s founder Juan Tripp created a U.S. monopoly on most international routes.

TWA had some international routes too, but they did not compete that much. Northwest also had routes to Tokyo. Pan Am had a wonderful international franchise under our protective bilateral aviation agreements with other countries, but no domestic service. The fares were very high and set by IATA, the International Air Transport Association, then a price fixing cartel sanctioned by the bilateral agreements and granted antitrust immunity by the U.S. government. Only a small percentage of the population could afford to fly, and the airlines agreed to generous union contracts, imbedded layers of management, and passed through the costs by raising fares. With few cost control incentives, Pan Am had many vice presidents and large departments that engaged in statistical analysis and planning.

Then in 1978 Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act. The first bill was introduced in Congress during the Ford Administration. I had worked closely with John Snow, the task force leader at DOT, who later became secretary of the treasury under George W. Bush. John had a PhD in economics as well as a law degree. John led the effort to send to Capitol Hill deregulation bills for airlines, railroads, and trucking. We worked closely with Steve Breyer, then an aide to Senator Kennedy who was a strong supporter of economic deregulation. (He is now a Supreme Court Justice.) The Carter administration carried through. Carter appointed Alfred Kahn, head of the CAB (Civil Aeronautics Board) and succeeded in getting deregulation legislation through Congress. They always gave us a lot of credit for initiating it.

Open Skies:

As deregulation was phased in, the Carter administration also began negotiating “open skies” bilateral aviation agreements that allowed competitive international service by other U.S. airlines. United, American, and Delta began to fly international routes, feeding their airport gateways with their extensive domestic service. This was the demise of Pan Am.

When United started flying to London from Chicago they had hundreds of flights bringing in people, collecting them in Chicago, and sending them off to London. Pan Am’s Chicago to London service had no traffic feed. Plus, fares could be set more competitively. Pan Am also was undercut by Freddie Laker and other low cost carriers that would come in and offer much lower fares. Meanwhile Pan Am had contracts with their unions to pay high salaries to their pilots and other employees represented by the teamsters and the IAM (International Association of Machinists). As I have indicated, in my judgment, Pan Am made a mistake by trying to buy a domestic system when they entered into a bidding war with Frank Lorenzo of Texas Air to acquire National Airlines. Pan Am wound up paying way too much for National, a small airline based in Miami with a very southern, easygoing culture in contrast to the high pressured New York culture of Pan Am. The different unions also had a hard time integrating the work forces. A lot of factors went into the eventual demise of Pan Am. The proverbial nail in the coffin, though, was probably the terrorist act that brought down flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. With its worldwide brand, customers feared that Pan Am was a prime target of terrorism.

Q: Did you work exclusively for Pan Am?

BLISS: Oh no. At different times, I represented United Airlines and US Airways on a whole range of domestic and international matters. I worked on a half dozen airline mergers and on suits between airlines. I also did some appellate litigation for Delta, Flying Tiger, Alaska Airlines, and American, indeed most of the major carriers at one time or another. Bill Coleman and I also represented the Washington Metropolitan Airports Authority on issues of governance. When the regional authority was created by Congress to take over the operation of National and Dulles [airports] from the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration), Congress did not want to relinquish complete control and established a congressional board of review that could overrule decisions by the airport authority’s board. Noise activists challenged the structure under the constitutional separation of powers doctrine We defended the authority twice before the Supreme Court and eventually worked with Congress to amend the statute to satisfy the constitutional critics. In working on this case, I got to know house transportation committee chair Norman Mineta, who later as secretary of transportation asked me if I would serve as Ambassador to ICAO.

Table of Contents Highlights:

Education

B.A. Principia College, 1963

J.D. Harvard Law School, 1966

Career

Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) 1969–1973

U.S. Department of Transportation, 1975–1976

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Council 2006–2009

Appointed by George W. Bush as Permanent U.S. Representative to ICAO, held rank of Ambassador