Documenting Human Rights Abuses in Argentina’s “Dirty War”

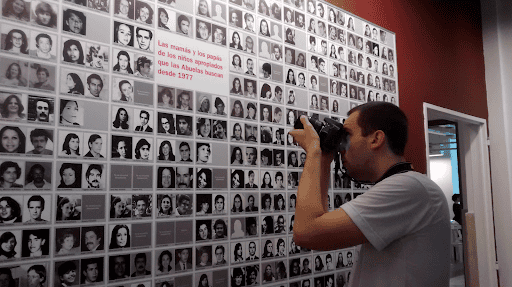

Franklyn Allen Harris, known to his colleagues as “Tex,” was born in Glendale, California and raised in Dallas, Texas. Harris joined the Foreign Service in 1965 and arrived in Argentina in 1977 during the so-called “Dirty War.” Alongside a colleague from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Harris documented nearly 14,000 cases of “disappeared” Argentinians who were kidnapped, tortured, and clandestinely executed by the Argentine military during the conflict. Thanks to these documentation efforts, thousands of families of the missing were given a platform for voicing their grievances.

During the late ‘70s, the Argentine government found itself embroiled in a fight against two communist guerilla insurgencies. One tactic employed by the Argentine military during the conflict was to “disappear” those suspected of collaborating with or assisting insurgents. As American Foreign Service Officer “Tex” Harris described it, “people were arrested and then disappeared, or people were just abducted from the street… a car pulled up, generally a Ford Falcon, several people got out of the car, grabbed the person, put him in the back seat of the car, and the individual was never seen again.”

“People were just abducted from the street… several people got out of the car, grabbed the person, put him in the back seat of the car, and the individual was never seen again.”

Tex Harris

When the Carter administration took office, the protection of human rights became a top policy priority. Harris, newly arrived in Argentina at the time of the administration change, opened the doors of the U.S. Embassy in Argentina to the concerned families of those who were believed to have disappeared.

“We worked the operation like a high turn-over doctor’s or dentist’s office,” Harris recalled. “We had two inside offices. Blanca Vollenweider (USAID) put the people in the office, and she took down on a five-by-eight card” personal information about them and their vanished loved ones. Harris would then personally interview every complainant in Spanish to document facts about each disappearance while Vollenweider was taking down information from the next person into the other office.

Throughout this process, Harris became close with a number of mothers who would regularly protest the disappearance of their children at the Plaza de Mayo – a prominent city square in Buenos Aires. “I would go to the Plaza de Mayo,” Harris said, “a 250-pound, two-meter fellow who is easy to spot, easy to point to, and lo and behold, the United States of America is interested in the disappearance of their children. That meant a lot to them.”

Despite attempts by Argentine authorities to intimidate him, Harris continued documenting cases. In the end, he and Vollenweider interviewed nearly 14,000 individuals. “We sent what was probably the largest airgram ever sent to the Department of State listing the names of the Disappeared,” Harris recalled, “about seven hundred pages in length.” Most individuals reported “Disappeared” were never found, but Harris and Vollenweider brought international attention to the human rights abuses of the Argentine state. Moreover, the families were able to take some solace in the fact that their disappeared loved ones had not been forgotten.