“With Ukraine, Russia is an empire. Without it, Russia is just another country.” The history between these two is long and often fraught with conflict. Before the current protests in Ukraine over relations with Russia, Ukraine had to fight to free itself from the Soviet Union. Official independence was declared August 24, 1991 and with it came its own host of problems. The United States was split between keeping the Soviet Union intact (and its reformist leader Mikhail Gorbachev in power), versus supporting Ukrainian democracy and self-rule. This ambiguity was highlighted by President George H.W. Bush’s much-criticized “Chicken Kiev” speech, in which he warned against “suicidal nationalism.” Eventually Washington decided to recognize Ukraine. However, its sizable nuclear arsenal, lingering Communist sentiments, the situation in Crimea, and the nature of the future government all became salient issues post-independence.

Jon Gundersen was the Consul General in Kiev (later spelled after independence in the Ukrainian way, Kyiv) at the time and tells of high-profile U.S. visits, including by Richard Nixon, working with Communist and nationalist Ukrainian leaders, and the development of a newly independent nation, including control over Crimea. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in April 2012.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“There was a real movement for independence”

Q: Was the ending of the Soviet Union sort of in the wind, did you see it at that time?

GUNDERSEN: I did begin to see it when I went to Ukraine, in late ’90. Initially there were just two of us, so I had a staff of one. By the end of my tour I had a staff of 80. So myself and the other officer, who was a fluent Ukrainian speaker, lived in an old Soviet-style apartment on the third floor. Ukraine was still very much a Soviet republic in the eyes of Embassy Moscow. And we began to report facts on the ground.

We gradually got a sense that the Ukraine was going to go independent. We’d talk to Party leaders, dissidents, labor leaders, and members of the Rada [Ukrainian Parliament]. They were beginning to sense that the center could not hold. Then CODELs [Congressional Delegations] began to come in.

[Ukraine] had a vote on sovereignty in March 1991, which was fairly overwhelmingly voted in favor of. This wasn’t independence, it was still under sovereignty… in the Soviet Union, but because the vote was so overwhelming, you had a sense that they weren’t going to stop there.

We started reporting about that, that there was a real movement for independence. Embassy Moscow didn’t agree. The conventional wisdom in the Bush I administration was that we could work with Gorbachev; we were beginning to sign arms control agreements and Gorby was a known entity. The thinking in Washington was, “Let’s deal with the devil we know, we’re getting these agreements, let’s not deal with this nationality, independence issue.”

Because we didn’t have classified communications capabilities in Kiev, my colleague, John Stepanchuk, and I had to travel virtually every weekend to Moscow to write secure cables….Sometimes Embassy Moscow would put “We do not agree with this” in a comment on our cables. So there was a little tension there.

We weren’t saying, “They will become independent,” Foreign Service people don’t make such categorical statements, but “There is a good chance that they will be pushing for more and more independence and we have to deal with this reality and have think about what our policy should be.” Would we recognize Ukraine’s claim as an independent statehood? What are the criteria for recognition? How do we coordinate with our NATO allies, etc. So it was an interesting time to be there….

Q: What were the Ukrainians saying? Was there a Ukrainian government at the time that could easily split off and become an independent government, or was there sort of a creature of Moscow?

GUNDERSEN: Well, they had a leader named [Leonid] Kravchuk. He used to be the ideological secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, but he was a crafty character and saw the way things were going. So he became more and more independent; he quickly changed to a black Nationalist hat, and discarded his red Communist hat. Meanwhile, the Rada had elections and elected some Rukh [a Ukrainian democratic, pro-independence party] people. So there was real, pretty open discussion on independence. And we were reporting that even the Communists were moving in that direction.…

Many of our cables were sent directly to the White House and shared in NATO. So there was a lot of ambivalence about whither Ukraine. I got what they called O-I’s, official- informal notes outside of channels from fairly high ranking people, who’d say, “Right on!” and “We agree with you.”

Bush’s “Chicken Kiev” Speech — “You can push for democracy, but not for independence”

Q: To my mind, if Ukraine goes, Russia’s no longer a threat. It’s like in the Middle East, if Egypt’s not going to fight, there isn’t going to be a war. This meant sort of our entire geo-strategic assumptions would have to change. Were we looking at it that way?

GUNDERSEN: I think that reflects exactly some of the discussion. In fact I have a letter from Paul Wolfowitz, who was at the time the Assistant Secretary of Defense for international security policy.

He was using our cables against some at State who would say, “Well, we have to work with the Soviets and Gorbachev. Let’s not push it too much.” The Pentagon’s thinking, in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, was driven by military, not political objectives. If Ukraine becomes independent, the thinking was, Soviet forces would have to retreat a thousand miles from NATO and it would no longer be a strategic threat.

And so they looked at it from a military perspective; they were less involved with arms control or other considerations. There were some in S/P, State’s Policy Planning Council, who agreed. However, most at State and the NSC [National Security Council] wanted to stick with the existing policy toward the Soviet Union. So we understand there were some real tough “Whither Ukraine” discussions in Washington. It came to a head when President Bush came to Ukraine…

Q: This is his “Chicken Kiev” speech?

GUNDERSEN: Yes… Bush I visited the Soviet Union in early August 1991 (it was still the Soviet Union) to work with Gorbachev, because they had come to the recognition, from their perspective, that they liked Gorbachev’s reform policies. We were signing arms control agreements. Bush was someone who placed great stock in personal relationships and he was comfortable dealing with Gorbachev.

But we also knew that they had to deal with the nationality issue. So Bush scheduled a trip to Kiev after Moscow. He was greeted by a million people in Kiev because he was seen as pro-democracy. The route was lined with people; it was a very joyous occasion. And he gave a speech to the Rada. He talked about democracy and self-determination and human rights and Ukrainian history. Not a bad speech generally.

However, two things he said became famous: he warned against “suicidal nationalism” and said that “Democracy does not mean independence.” So he was, in effect, telling the Ukrainians, “You can push for democracy, but not for independence.”

I only saw the speech a couple of hours beforehand. I told the speechwriters: “This is going to go down really bad, because of these two lines.” And those were the things that were picked up by the press. I think it was Washington columnist Robert Novak who called this speech the “Chicken Kiev” speech. The Ukrainian-American community here reacted very strongly and negatively to the speech as well. All the good things in the speech were soon forgotten.…

One of the results of the Bush meetings was that the Soviets were becoming increasingly suspicious of the Ukrainians and where they were going. So they sent down [Soviet politician Gennady] Yanayev, one of the leaders of the subsequent coup to remove Gorbachev from power, to spy on what Bush and Kravchuk were talking about.

Kravchuk and Bush wanted to have a one on one meeting, so they told me to “Talk to Yanayev, so we can have a private discussion.” I have a picture of a very worried looking Yanayev sitting there with Bush and Kravchuk. Then Bush and Kravchuk disappeared. I think that was one of the key events that caused the coup makers to act. I think Yanayev reported back to his buddies in the Kremlin, but not Gorbachev, that: “Ukraine’s going to go independent, we need to do something about it.” The coup occurred a month and a half later.

Nixon, Kravchuk, and the “Goddamned Intellectuals”

Q: From your perspective, were you able to get out in Kiev and get a feel about what would happen?

GUNDERSEN: I think we were given an unusual and almost unexpected degree of access, because this was a time when the Soviet Union was changing, Gorbachev was encouraging this more open attitude. Although obviously they didn’t want to go all the way.

Gorbachev believed you could have a reformed, more open, kinder society and keep the Soviet Union together. And initially, it was two of us, myself and a guy named John Stepanchuk, who was a fluent Ukrainian and Russian speaker. We traveled all over. We talked to Party people and Rukh dissidents….

Q: How about the Party, the Communist Party in Ukraine? Where was it coming out?

The Party had always been very loyal to Moscow, very hard line, because they knew that many Ukrainians, especially Ukrainians in the West, were anti- Party, anti-Russian, so they needed to prove their loyalty to Moscow. Vladimir Shcherbytsky, the Ukrainian Party leader until 1989, was one of the most loyal followers of [General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid] Brezhnev and a member of the Soviet Party Politburo [governing body of the Soviet Union]….

After Ukraine voted for sovereignty in the spring of 1991, it was clear where they were going. We started getting visitors like [former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew] Brzezinski, Kissinger, Nixon and all sorts of CODELs [Congressional delegations].

Nixon, for example, came on his own. This was a unique opportunity for a Foreign Service officer to sit down with a former president and escort him around for two days. Despite his obvious flaws, Nixon, even at 80, was a very sharp, realpolitik guy. We met with Kravchuk.

After we came out of that meeting Nixon said, “This guy is smart and he will be the type that will break with the Soviet Union if he thinks it’s necessary for his survival.” Kravchuk was a cynic, sort of like Nixon, who recognized they were kindred spirits. As much as anyone, Nixon probably foresaw what was going to happen regarding the breakup of the Soviet Union.

We also saw some of the dissidents, as Nixon wanted to see everyone…. They were mostly intellectuals with little idea about governing. In front of Nixon, they argued about what sort of Ukraine would emerge, whether it would be along the lines of a Jeffersonian democracy– they were quoting Rousseau and Montesquieu.

And Nixon asked, “How do you run the government? Who’s in charge? Where are your alliances?” And Nixon sort of turned to me and he said, “Goddamned intellectuals!”

“How do you collect the garbage?” It was funny, you’re sitting next to a former president and he turns to you and says something like that. And this was after he had met with Kravchuk, they sort of, I wouldn’t say bonded; let’s say they understood one another….

Flying the Coup

The head of the KGB, I think his name was [Vladimir] Kryuchkov,[Sergey] Akhromeyev, former military Chief of Staff, and [Gennady] Yanayev, Gorbachev’s Vice President, who had just been to Kiev, decide to act while Gorbachev was vacationing [in the Crimea].

When that the coup happened in August ‘91, Ukrainians basically were set on independence, so Kravchuk immediately denounced the coup. Unfortunately I was in Washington on consultations when this occurred, so I rushed back to Ukraine….

My first thought when it occurred was, the hard-line Communists are going to return to Brezhnev-era policies and it would be difficult for us to influence the course of events.

At the same time, RUKH, the democratic movement we had been helping, basically took over the government in Kiev. I got a call from the head of RUHK telling me, “We know you’re looking for a building to house your consulate. Would you like a building? And they offered us the Kiev Communist Party headquarters, which is the current U.S. Embassy there. So that’s how we got that building….

There were concerns that there was not a democratic or ethical tradition about how one governs [in Ukraine]. There wasn’t the idea that governments should be held accountable. As an optimist and believer in the better nature of human beings, I must admit I did not foresee the extent of the current corruption…

We did report a little about the corruption in the society, about the weakness in the democratic forces, about Kravchuk and the local KGB being interested in holding power and getting the fruits of selling state assets. But we didn’t say, “Well, this is going to doom the Ukraine.” We thought that Ukrainian independence was a positive thing, which I think in the larger sense it certainly was, but we didn’t prophesize Ukraine would have all these problems.

We actually reported something along these lines: “Ukraine has the potential to be a stabilizing force, because it’s a rich country, it’s got cultural resources, it’s got a lot of smart people, and it has a strategic location.”…

Independence and the Nuclear Arsenal

So we thought they would muddle through and they did muddle through, but obviously they’ve never developed into the type of… reasonable, stable country, as we had hoped.

And we saw progress right after independence. Businessmen came to open hotels and to invest. But we began to hear that most of the officials were all on the take; you had to pay money to get things done, that a Ukrainian mafia was developing. So we sensed that there were real problems in the society.…

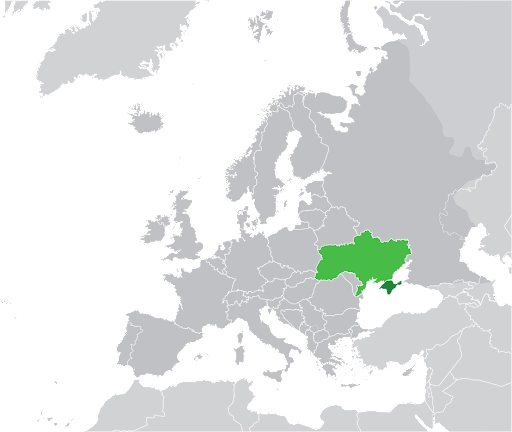

Here’s this big country of 52 million in the heart of Europe, which, when it became independent, became the third largest nuclear power in the world, because of all the nuclear weapons on Ukrainian soil. And they were sister Slavs, “little Russians” they would say. So when Kiev declared its independence, we at the consulate wanted to recognize Ukraine right away.

Embassy Moscow wanted to check with the Soviets first. They delayed recognition to allow for meaningless things like getting our defense attaché in Moscow accredited to Ukraine. We felt these little things were both unnecessary and small ball as this was a historic moment. So when Ukraine voted for independence on December 1, 1991, in overwhelming numbers, the Canadians and Scandinavians recognized them right away, but NATO as an alliance was reluctant to do that as was Washington…

The State Department eventually came around to accepting the reality of independence. Secretary Baker came to Ukraine– he visited it and the other newly independent states in January ’92. He turned the policy around 180 degrees and basically declared: “Yes, Ukraine’s going independent, obviously the Baltic Republics are and probably these other constituent Soviet republics are and we have to be ahead of the curve.” Right after his trip we recognized Ukrainian independence immediately and we said all the right things. The Ukrainians were very happy about it and so it was a sea change and we started getting aid programs the Ukrainian-American community and ourselves had been pushing for….

I was very much involved, sometimes as a policy maker, sometimes delivering messages directly to Kravchuk, such as: “We will be able to do all these things if you abide by international covenants and agree to get rid of the nukes on your territory.”

Q: You basically wanted them to go to Russia, where we would deal with them?

GUNDERSEN: Or to be destroyed. Remember at the time we were negotiating bilateral treaties with Moscow which would allow us to control nukes more closely in Russia. However, there were forces in Ukraine, on both the right and left, who were saying, “Let’s keep the nukes, they are how we will get respect as a new state, by having these nukes.” Of course, the Russians were also pushing to get the nukes out of Ukraine.

There were also a lot of countervailing forces. There was a strong anti-nuke movement because of the reaction to the Chernobyl reactor explosion. At the same time, as I mentioned, some politicians believed that the nukes could give Ukraine legitimacy and perhaps great power status or, at least, that they could be used as a bargaining chip with the Russians.

So we worked out what was eventually called the Lisbon Protocol in early ’92. The Ukrainians agreed to get rid of all their nuclear weapons. In exchange they would get certain aid and would have a pathway to membership in international institutions. Those negotiations were very delicate and touch and go. I remember midnight calls to Kravchuk’s villa delivering a curt message from the Secretary of State: “You’ve got to agree to this by this date or else.” And he signed. Of course, Moscow was also pressuring him as well….

“It was a point of contention about who controlled the Crimea”

It was a point of contention about who controlled the Crimea. The Crimea had been Russian territory, but had been given to Ukraine as a gift by Khrushchev in the Fifties. Of course, Moscow could never imagine that control of Crimea would have be an issue, because the Ukrainian Communists were very loyal. It was just sort of an offhanded gesture.

We had no real problem about the Russians maintaining a fleet there, as long as it didn’t jeopardize our Sixth Fleet and Ukrainian sovereignty.

That negotiation went on for a few years after I left and they eventually agreed to a long-term lease of Sevastopol [Ukrainian port in Crimea on the Black Sea].

Q: Were there forces in Ukraine that wanted to preserve the Soviet Union?

GUNDERSEN: There were forces. There were still members of the Communist Party who would have liked to have kept the Soviet Union. But they were in a minority and we felt that they would not be able to win any parliamentary election.

The former Communists under Kravchuk and [Leonid] Kuchma, the next Prime Minister, liked being independent. They weren’t democrats, but they didn’t want to be under Moscow. So we didn’t think that was a real possibility to restore the Soviet Union….

We were also aware that the dissidents were not united. Ukraine didn’t have a figure like a [Vaclev] Havel or a [Nelson] Mandela who might have led the country to more stability. You had a lot of petty infighting even among the democrats, as well as the Communists….

All the military had been trained in the Soviet Union by Moscow using their military approach, which is a top-down approach. We never felt that there was a Napoleonic coup possibility, where the military would take control, because they always had operated at the behest of the Party, so they weren’t like in Egypt or Turkey an independent force….

I probably have to admit I was more optimistic than I should have been. We had fought the good fight, we knew the people involved. We thought it was and I think it remains very much in the U.S. national interest to have an independent Ukraine.

So we felt that it would become a relatively stable, relatively democratic country which would be increasingly integrated into Europe. It has maintained its independence. It hasn’t been a total disaster.

So in a larger sense, I think the record has been mixed, but obviously it’s disappointing that Ukraine hasn’t developed into a more democratic society and that corruption is endemic.

Nonton Movie I think it’s a good thing to do, how about you?

Nowadays there must be a change for us all, therefore your article very useful thank you Daftar Poker

Thank you for sharing your info and i hope u can visit my website

my website :

bokep kualitas hd

movie kualitas hd

nonton movie bokep full hd

I would be so thankful if you did that