It was one of the most horrific events in U.S. diplomatic history. On August 7, 1998, between 10:30 and 10:40 a.m. local time, suicide bombers parked trucks loaded with explosives outside the embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi and almost simultaneously detonated them. In Nairobi, approximately 212 people were killed, and an estimated 4,000 wounded; in Dar es Salaam, the attack killed at least 11 and wounded 85. The attacks were later traced to Saudi exile Osama bin Laden and took place on the eighth anniversary of the deployment of U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia.

On August 20, President Bill Clinton ordered cruise missiles launched against bin Laden’s terrorist training camps in Afghanistan and against a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan, where bin Laden allegedly made or distributed chemical weapons.

In November 1998, the United States indicted bin Laden and 21 others, charging them with bombing the two U.S. embassies and conspiring to commit other acts of terrorism against Americans abroad. To date, nine of the al Qaeda members named in the indictments have been captured. Prudence Bushnell was Ambassador to Kenya at the time and relates the harrowing events of those days. She was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in July 2005.

Read her complete oral history here. To see a video interview with Ambassador Bushnell, go to our sister site, usdiplomacy.org. To listen to a podcast, go here. For another perspective, you can read the Accountability Review Board on U.S. Embassy Nairobi bombing. Read about other Foreign Service officers who died in the line of duty and about the threat against Embassy Rabat that the Department did not respond to. Read about the 1996 Khobar Tower bombing.

Prelude to a Disaster – Glaring Problems with Embassy Security

BUSHNELL: In the ’90s, President Clinton felt compelled to give the American people their peace dividend, while Congress thought that now that the Cold War was over there was no need for any significant funding of intelligence, foreign affairs or diplomacy. There were discussions about whether we needed embassies now that we had 24-hour news casts, e-mail, etc. Newt Gingrich and the Congress closed the federal government a couple of times. Agencies were starved of funding across the board.

Needless to say, there was no money for security. Funding provided in the aftermath of the bombing of our embassy in Beirut in the ’80s that created new building standards for embassies and brought in greater numbers of diplomatic security officer dried up.

As an answer to lack of funding, State Department stopped talking about need. For example, when we had inadequate staff to fill positions, State eliminated the positions, so we no longer can talk about the need. If there’s no money for security, then let’s not talk about security needs. The fact of increasing concern at the embassy about crime and violence was irrelevant in Washington. So was the condition of our building.

“I thought it was dumb to invest more capital in a building that would never be considered safe”

The first day I walked into the Chancery I knew something had to be done. Here was an ugly, brown, square box of the concrete located on one of the busiest street corners in Nairobi. We were situated across the street from the train station. Street preachers, homeless children, muggers, hacks and thousands of pedestrians came by our threshold every day.

The security offset prescribed by the Inman Report in the aftermath of the truck bombing of our embassy in Beirut in the ’80s, was non-existent. Three steps from the sidewalk and you were in the embassy.

In the back we shared a small parking lot with the Cooperative Bank building which was a 21-story building. We may have had about 20 feet of offset from the rear parking lot, but no more. We had an underground parking lot, which was inadequate, and we were squatting on some space in the front, but that was it.

I had learned before I got to Nairobi that the Foreign Buildings Operation, now Overseas Building Operations, was planning a $4-7 million renovation of this building that was unsafe and much too small for us. Having spent three years in African Affairs dealing with an assortment of disasters, I thought it was dumb to invest more capital in a building that would never be considered safe. There just was no way to protect the building. I suggested that FBO sell the building and pool the proceeds with the money proposed for the renovations to buy a new site. Washington’s response was somewhere between “Are you nuts?!” and “Get out of the way, the renovation train has already left the station.”

In 1997, I was told that we were under what was deemed to be a credible threat from a Somali quasi-humanitarian group called al-Haramain. I was also told that the intel side of the Washington interagency wanted to let things unfold to see where the leads would go. I reported this back to State, along with measures we were taking, but got no response. When I learned that the arms the group was waiting for were allegedly on their way, I asked the Kenyan government to break up the organization. [Kenyan President] Moi personally assured me they would comply. Some of the members of al-Haramain were deported and life went on.

Then I got word of a threat from the Lord’s Resistance Army, a rebel group in northern Uganda. Again, we advised Washington and again we got nothing back. Meanwhile we continued to do everything we considered reasonable and cautious. I remember that in early 1998 a delegation of counter-terrorist types visited. I met with them in the secure conference room, and when they ended with the pro-forma , “Is there anything we can do for you”? I angrily declared they could answer the god-damn mail. The cursing was intentional because I wanted them to see how frustrated and annoyed I was.

When I returned to Washington on consultations in December of ’97, I was told point blank by the AF [State’s Bureau of African Affairs] Executive Office to stop sending cables because people were getting very irritated with me. That really pushed up my blood pressure. Later, in the spring of ’98, for the first time in my career I was not asked for input into the “Needs Improvement” section of my performance evaluation. That’s always a sign! When I read the criticism that “she tends to overload the bureaucratic circuits,” I knew exactly what it referred to. Yes, the cables had been read, they just weren’t appreciated.

In the years since the bombing, I learned just out just how much I did not know about U.S. national security and law enforcement efforts against al Qaeda. The information was highly compartmentalized, on a “need to know” basis and clearly Washington did not think the US ambassador needed to know. So, while I was aware of the al Qaeda presence and various U.S. teams coming and going, I did not know, nor was I told, what they were learning. When the Kenyans finally broke up the cell in the spring of ’98, I figured “that was that.”

August 7 – “I was pretty sure I was going to die”

On Friday, August 7, we started another business day as usual. The DCM [Deputy Chief of Mission] was on leave. Our Political Counselor was acting DCM and I had asked him to preside over the Friday Country Team meeting [with senior representatives of the sections and agencies at post]. I was finally successful in scheduling a meeting with the Minister of Commerce to talk about an upcoming U.S. trade delegation, a big deal given how we stiff-armed Kenya –so I was not present.

I remember asking that the Country Team discuss how our newcomers were settling in and whether we were reaching the right balance on issues of security alerting but not paralyzing people to the dangers. In retrospect, that was a very ironic conversation.

The office of the Minister of Commerce was in the high-rise building across from our small rear parking lot. I walked across with two colleagues from the Department of Commerce, teasing my driver Duncan who was escorting us that he should be holding a little American flag we flew for official government calls. The Minister’s office was on the top floor.

As was the case in many official meetings, the Minister had invited the press to ask questions and take photos before the real talk began. A few minutes after they left, we heard a loud “boom.”

I asked, “Is there construction going on”? It sounded like the kind of boom you get when a building is being torn down.

The Minister said, “No, there isn’t.” He and almost everybody else in the room got up to walk to the window.

I was the last person up and had taken a few steps when an incredible noise and huge percussion threw me off my feet. I’ll never know whether I totally lost consciousness or whether I was semi-conscious, but I was very aware of the shaking of the building.

I thought the building was going to collapse, and I was pretty sure I was going to die. At the same time I was calmly thinking “this building is going to fall and I’m going to die,” I was physically steeling myself for a fall. I vaguely remember a shadow, like a white cloud, moving past me and the rattle of the tea cup.

Then I looked up. With the exception of a body prone on the other side of the large office, I was the only person left in the room that had held about a dozen people before the explosion occurred. Almost simultaneously, the man I took for dead raised his head, and one of my Commerce colleagues returned.

My colleague rushed in saying, “Ambassador we’ve got to get out of here!” I tend to be calm in emergencies and I was probably in shock and maybe denial because I didn’t want to leave the floor until we made sure that everybody else was out. We met up with a couple of people including the elevator operator literally wringing his hands saying, “Sorry, I’m so sorry, oh sorry, sorry!” For some reason I thought the building had been bombed because of a nasty banker’s strike that was taking place.

We were, after all, in the Cooperative Bank Building. So, off we went, down an endless flight of stairs. I have no idea how long it took, literally no idea. At every landing we would have to climb over the steel fire doors that had been blown in. Debris, blood, shoes and pieces of clothing were scattered at every floor.

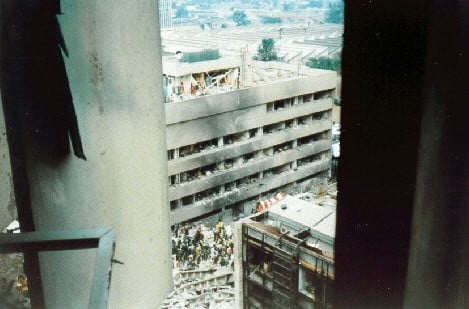

What I did not know was that around 10:32, as the Country Team was meeting in my office, a truck with 2,000 pounds of explosives drove into the small rear parking lot I had walked across earlier. The lot was squeezed between the embassy, the Cooperative Bank Building, where my Commerce colleagues and I went to meet with the Minister of Commerce, and a seven-story general office building.

The truck drew up to the guarded entrance to the underground parking lot of the embassy. One of the two occupants got out and demanded entry. The guard refused and tried to alert the marines via radio. The perpetrator then hurled a stun grenade (the noise we and thousands of other people first heard), then ran. Seconds later, his companion detonated the explosives. The two tons of energy that hit the three buildings surrounding the parking bounced off and over the bricks and mortar with devastating effect.

Two hundred thirty people were killed instantaneously. Over 5,000 people were injured, most of them from the chest up and most of them from flying glass. Vehicles and their occupants waiting for the corner traffic light to change to green were incinerated, including all passengers on a city bus. The seven-story office building next to the embassy collapsed and the rear of our chancery blew off. While the rest of the exterior of our building had been constructed to earthquake standards, the windows shattered, the ceilings fell, and most of the interior simply blew up.

Forty-six people died — about a quarter of the occupants — while others were struck or buried by rubble. All of the cars in the parking lot caught fire, which spread to the top of our generator. On the opposite side of the building, all of the windows blew in. In my office, the Country Team ducked as the windows blew, then crawled downstairs and exited the building along with everyone else who was still able. The acting DCM asked for volunteers to go back in and rescue colleagues, as the medical unit staggered onto the sidewalk and set up triage and medical help.

The two front office managers began to record the names of people as cars still fit to drive were flagged down and the injured sent to hospital. Thousands of people were drawn to the scene, many of them crawling over the rubble of the collapsed seven-story office building to try to save those who were buried. Some of them climbed into the rear of the embassy to lend help and, some, to loot. All this went on while, unaware, my colleague and I descended those endless flights of stairs in the Bank building with hundreds, maybe thousands, of Kenyans pressed together so tightly that I could barely keep my feet on the ground.

All I kept thinking was that I just needed to get out of there, to get to the Medical Unit and we would be okay. At one point, the slow parade of people came to a standstill. Some people yelled, “Hurry up, move; there’s a fire”! As smoke wafted up the stairwell, I thought for the second time that I was going to die. Again, it was a peaceful thought because at least I’d be asphyxiated and not burned to death. Everyone around us remained just as calm.

When we finally exited the building, I looked across the street to see thousands of people behind a cordon gawking in shock. My colleague exclaimed, “Ambassador, there’s press, put your head down!” He took the back of my head and literally pushed it down. Members of the press present at the beginning of the Minister’s meeting were still in the area when the bomb was detonated. (Much later a group of Kenyan photographers won the Pulitzer Prize for the bombing photographs, the first time that black Africans had ever won the Pulitzer Prize.)

Because I was looking down, my first sight of the bomb’s impact were shards of glass, twisted steel and, all of a sudden, the charred remains of what was once a human being. That’s was caused me to look up. What I saw was fire (hence the smoke in the stairwell), rubble, destruction and the remains of what had been the rear wall of the chancery. A few steps further and we met the acting DCM coming around the corner. He looked at me very calmly and said, “Hello Ambassador.” I was astounded and very reassured that he seemed so calm. Maybe things were not as bad as they looked. What I didn’t know was that, having organized and helped the team that returned to the building to help the buried, dead and wounded, he was now searching for his wife, like us, in shock.…

The information about what had happened and how people were doing came in waves. It got worse and worse as time went on. I mentally kept track of the people I saw or heard from and those I didn’t as I learned that there were looters as well as people who wanted to help who got into the embassy from the rubble in the parking lot.

I learned that our Marines had been sitting in their van outside the embassy waiting for one of their colleagues to cash a check when the bomb went off. The one who went in to get the money was killed. Another fell down the elevator shaft but returned with broken ribs from the hospital to help in the rescue. I learned about the janitor who put his life at risk to turn off the generator before the water hit our electrical wires. I learned about acts of incredible courage and terrible deaths.

As to security perimeter…that had been taken care of during the first hour. The Marines and a visiting security team donned helmets, flak jackets and guns and grimly kept people away. Kenyans who arrived on the scene to help, or not, were incensed.

Too many dead, too many wounded

As the day went on, the nightmare grew. Too many dead, too many wounded. Hospitals were flooded with thousands of walking wounded, most bleeding terribly from wounds to chest and face. … I returned to our operations’ center at AID as soon as I could. Can’t remember everything we did but I know I was incredibly grateful for the fact that we had a large mission with lots of willing hands and a senior team that was alive and experienced enough to take over when necessary.

I was also thankful for the experience of having handled disasters before so I could provide the kind of instructions that would hopefully help save lives. About ten that night, I left the ops center in the good hands of AID and embassy officers who could cope and went home exhausted. I was too tired to even wash off the clots of blood stuck in my hair.

Q: The second day you woke up, I assumed washed your hair?

BUSHNELL: The next day, yes, I washed my hair. To be exact, Dick, my husband, washed my hair. Bandages on my fingers, hands and arms from superficial wounds prevented me from putting them in water so Dick did it — one of those moments that would be accompanied by schmaltzy music in the movies.

It had been a horrible night. The phone in our bedroom kept ringing and when I answered, I’d get silence. I honestly thought that perps were telling me there were more of them out there and they knew I was still alive….

Downtown, people had worked all night to dig survivors out of the collapsed office building. At our operations center, the night shift had been relaying information to the Washington task force (because Nairobi was eight hours ahead we usually interacted during evening and night hours) and keeping tallies our dead, wounded and missing. We had reached forty-something and were still looking for both Kenyans and Americans.

I needed to see the embassy so I went there first. Reinforcements for the Marines providing perimeter security had still not arrived but everything was calm. Our Security Engineer had established a lean-to office on the sidewalk and escorted me through the remains of our building. The devastation inside had a deathly stillness to it. I laid roses sent to me by Sally, the Permanent Secretary of the Foreign Ministry, on the steps leading into the building because it had now become a sacred place….

American members of the community had gone to sit with those waiting for news of the whereabouts of loved ones, or reeling from information of the death toll. I visited a couple of them that day. Sue Bartley, spouse of our Consul General, Julian Bartley, was already aware that her son had been killed and was holding out the hope that Julian would be found alive. We were sure that he was not but did not want to stamp out that hope until we found the body. Julian, like other of our African American colleagues, had been mistaken for Kenyan and taken to one of the many over-crowded morgues around the city.

It was not until Sunday afternoon that he was found. One of our newcomers, Howard Kavaler, having learned that his wife, Prabhi, had been killed, decided to leave post immediately with his two daughters. Howard was amazingly kind to me when we said goodbye….

Dealing with Grief

The U.S. military had sent a number of doctors and counselors to help the Kenyans, because the Kenyan medical establishment was overwhelmed. Some of them did a good job and some did not. Grief counselors were pretty much an anathema to the Kenyan communities.

The very first person to arrive to help the embassy community was the Regional Psychiatrist from Pretoria. He decided that all employees of the mission should go through debriefings and he used military counselors to help.

I think the results were mixed. We decided to do it at the Residence, because we wanted a safe comfortable place, and the Residence was a very pleasant spot. We also decided to have mixed groups of Americans and FSNs. Our motives were good but I’m not at all sure the decision was the right one.

I was desperately trying to make good decisions – we all were – but I’m not sure all of them helped as much as we had hoped.

I did have a separate debriefing for the Country Team because I could not talk as openly with other groups. Plus, some happened to be out of country that day and we wanted to integrate everyone into one team again.

My husband, Dick, played an important role in getting people to these debriefings. He is one of the most cheerful souls I have ever come across, the kind of man who almost literally wakes up singing, full of energy and enthusiasm. He made sure that all of the FSNs attended the debriefings and made all of the arrangements at the Residence. At one time we had five or six debriefings going on simultaneously.

Q: Did you find this briefing therapeutic?

BUSHNELL: I found it very useful. In the psychiatric community now there is some controversy as to whether these debriefings are good or not, but I’m glad we did them because I thought the “stiff upper lip” and “move on” tradition of the State Department was completely inappropriate to us.

Q: Which is the old attitude, I mean get on with it.

BUSHNELL: Right. So, as a gesture that I cared enough about the people under my leadership to take advantage of this was important to me, and I will stand by that. The concern was that there were some people for whom debriefing may discharge really high emotion and be more negative than positive, and I understand that. I’m still glad I did it and I would do it again tomorrow.

The briefing went like this. Everybody in the group was asked the question, “Where were you at the time of the bombing?” So, one would simply get the information out. By doing that one was able to see the different perspectives people had from those who were in the building to those who were out of the city or even out of the country.

The next question was, “How did you feel then and what are you feeling now?” That’s probably the part that could be more controversial. It was for me a critical question to address. I was the only woman on the Country Team and I was the leader. I was so aware of the fact that I had failed in my mission to keep people safe. Even though I had tried, I had failed. It was helpful to share that and to get the full-fledged loyalty of the team.

While we never put words to it, it was certainly obvious in retrospect that we would have done anything for one another. I had a senior staff committed to dealing with the incredible challenges in ways that focused on taking care of our people. How much was directly due to the debriefing, I’m not sure but I know it was important.

Q: Was there a different attitude toward this from the Kenyan side of things? I mean, Americans are pretty prone to speak out, particularly the newer generation.

BUSHNELL: Dealing with post-traumatic stress and talking openly about feelings continued to be a big issue in the community for a long time to come. Among the Kenyans, therapy is not a part of the culture. We had counselors available for months, and once the military counselors left we tapped into the local Kenyan counseling community — not just for embassy employees but the Nairobi community at large.

A study on the effectiveness of the counseling that was done after I left post found that Kenyans did not take advantage of it, nor did they find it particularly helpful. Far more helpful for them was their church community and their families’ support.

Q: I think Americans have been almost trained to accept counseling.

BUSHNELL: Americans maybe, but Foreign Service people, no. After all, if you see a counselor, you have to ‘fess up for a security clearance. A lot of American employees feared that getting counseling would jeopardize their careers and so refused to go….

Managing Chaos and “Disaster Tourists”

That evening the FEST team — I think it stands for Federal Emergency Support Team –and the Fairfax County Search and Rescue Squad finally arrived, along with a host of military personnel, as well as FBI agents. Suddenly, we went from having to manage chaos and tragedy to managing chaos, tragedy and hundreds of people.

The fact that no one came with a specific role or objective made things worse — something I subsequently talked about

at length: if you’re going to help people in chaotic circumstances you really need to have your act together because, if not you create additional management issues for people already in crisis. (Read also about Ambassador G. Philip Hughes’ experience with First Lady Nancy Reagan’s ill-timed trip to Mexico City after the earthquake.)

The Department at this time had very little experience with the kind of situation Nairobi and Dar were in. We’re very good at evacuating people and we’re good at taking out our dead. But a terrorist attack that leaves some dead and some not was something we had much less experience with. So, there were inevitable run-ins.

Our Security Officer, for example, was prohibited from entering the AID building, to which we had transferred operations, because his embassy ID been lost in the attack. One of my most senior people, meanwhile, wanted to resign out of frustration that no one in the new group was listening to him. I pulled everyone into our operations center and laid down the law.

I told everyone to “Take a good look at me. I am the Chief of Mission. This is my mission and nothing happens unless I say it happens. Here is the Acting DCM. If I’m not here, he’s the one who says what’s going to happen.” We then organized the visitors so that rather than meeting with all these little groups separately, they would coordinate among themselves, and I would meet with a couple of them every morning or twice a day. Over a period of hours and days things settled down.…

The worst three days of the crisis were the first three: Friday, when we were blown up; Saturday when the rescuers finally arrived to create even more chaos; and then Sunday when we held a memorial service for the Americans and dealt with the international news media. Of course they wanted a press conference. I did not want any photographs taken, because I looked pretty banged up but was persuaded otherwise.

I smile, because about a week later my OMS came up to me and said, “You know, Pru, I really shouldn’t be saying this, but I’ve been seeing pictures of you on television and in the newspaper and I have to say it’s good that you got your hair done a few days before we were bombed. As bad as you looked, your hair was okay.”…

When Secretary Albright did come I had two conditions: that we not have to prepare briefing papers, because we had lost all of our computers, and we had nothing, nothing. And the other, that she not spend the night, because the security involved in that would have been so astronomical. As it turned out, the plane had problems in Dar, where she had first stopped, and she had to cut her trip short.

Rather than meet with the opposition political figures one by one, we invited them to a wreath-laying at the site of the embassy and the building that had collapsed. They were further outraged. I, in turn, became almost as angry with them. We had personally supported all of them and funded quite a few.

I was so mad at them that I refused to see them until Christmas. I didn’t invite them to my house, I cut them off. The Country Team advised me to contact them earlier but I had decided to hell with being ambassador. These politicians were human beings to whom I had paid respect and support who chose to make a spectacle of circumstances for no reason but political show. Others at the embassy continued meetings but I didn’t until December when we finally reconciled with all but one.…

We also had to manage Washington, because once the press left and the crisis task force disbanded, we lost a cohesive way of dealing with the myriad of issues we faced. The Africa Bureau was as usual flooded with problems all over the sub Sahara and we were just one of many problems.

The Department returned to business as usual much faster than we were ready and we felt that there was a lack of understanding as to just how blown away we literally had been.

People would start saying, “Well, you didn’t respond to our cable, what’s wrong with you”?

“Well, our communication system had been blown up.” For a while I was interacting with the Department via Hotmail — we were lucky that AID had an Internet link.…

Once the Secretary and her entourage came and left, we received what I began to call the “disaster tourists.” Well-meaning people from various parts of Washington who couldn’t do a thing to help us.

In November I sent a cable to Washington requesting by name the people we wanted to visit. The response was “Now wait a minute, you’re complaining about the visitors who are coming and now you want others. You’re sending very mixed messages here.”

They didn’t seem to understand the difference between those VIPs who could be part of the solution and those having their photographs taken in the remains of the embassy….

“We don’t do memorials!”

FSNs, in particular, were concerned about the transfer cycle and how their new bosses would interact with them. Would they understand the extent of the damage and trauma? Johnnie Carson (at left), who had been DAS [Deputy Assistant Secretary] in African Affairs, was to replace me which was great news, but many of the others were unknown.

On the Washington end, MED held briefings to alert people as to what to expect. In Nairobi, the DCM – who, fortunately was staying – and I met in small groups with all of the FSNs to give them whatever information we had about the building to which they would be moved pending the construction of a new embassy, and to listen to their concerns.

One, which had come up earlier, was the disposition of the old chancery and grounds. Fortunately, it was too damaged to every use again, so we pulled it down. (Among the myriad of decisions was whether to blast it down or chip it down. I decided that Nairobi residents did not need to hear another blast from that spot, so opted for chipping. Oh, the complaints!).

The grounds had been leased to us by the Kenyan government for 99 years and we still had lots of time left. People voiced concern that if we returned the land, one of the land-grabbing members of Moi’s cabinet would seize it to construct heaven knows what. I went back to FBO [Foreign Buildings Operation] requesting that we construct a memorial park and began another round of mutually irritating conversations — “We don’t do memorials!”

My instructions were precise: hand it back. We did, but not before I cornered every senior member of Moi’s government with the request that he support the establishment of a memorial park.

The local American business organization had offered to landscape it and provide money for upkeep. I took a cue from the Vietnam Memorial in Washington and asked that a wall be constructed with the names of everyone who had died in the attack so that their children and grandchildren could come and remember them.

By the time I left plans were well along and the park remains there today, although I understand it is short of funding. I did my best to implement a good exit strategy and noticed that people were taking our departure fairly easily. At first I thought this was great.

Then self-satisfaction turned to irritation and then hurt. After all we had gone through, no one was going to organize even a standard good-by ceremony? The day before our departure, Dick and I had inevitable errands which included stopping by the DCM’s Residence.

We pulled into the driveway and there, lining each side were all of the mission employees. They had worked up a surprise party for me! I was shocked. It was one of the most memorable points of my life, because the message was, “Hey, Ambassador, you who have prided yourself on having such a good pulse on your community didn’t know what we were doing. We put one over on you! We did this as a community. It’s okay, you can go.”

It was just such an incredible message. If it were a movie, you would have had schmaltzy music and garish sunsets. Moi and I had our final tiff at the formal going-away ceremony. He was mad, I learned later, that Washington was not sending a white male to replace me and decided it was my fault. Fortunately, he did confirm that we could use the land for a park, so we got what we wanted in the end.