Paris is one of the most beautiful and glamorous places in the world. But like most urban centers, it also has a dark side, as shown yet again by the horrifying assault on the satire magazine Charlie Hebdo and the horrific terrorist attacks just a few months later on November 13, 2015, which killed more than 125. In these excerpts, Foreign Service officers recall the violent, disturbing time of the 1980s, when Paris – and the U.S. Embassy in particular – were the target of a string of attacks, usually orchestrated by Middle East terrorist groups. It made Paris “the most dangerous assignment I’ve ever had,” in the words of one FSO. In the span of just a few short years, there was an attempted bombing of the embassy, a terrorist explosion on the street where one official lived, an attack against two other officials, and the assassination of a military attaché.

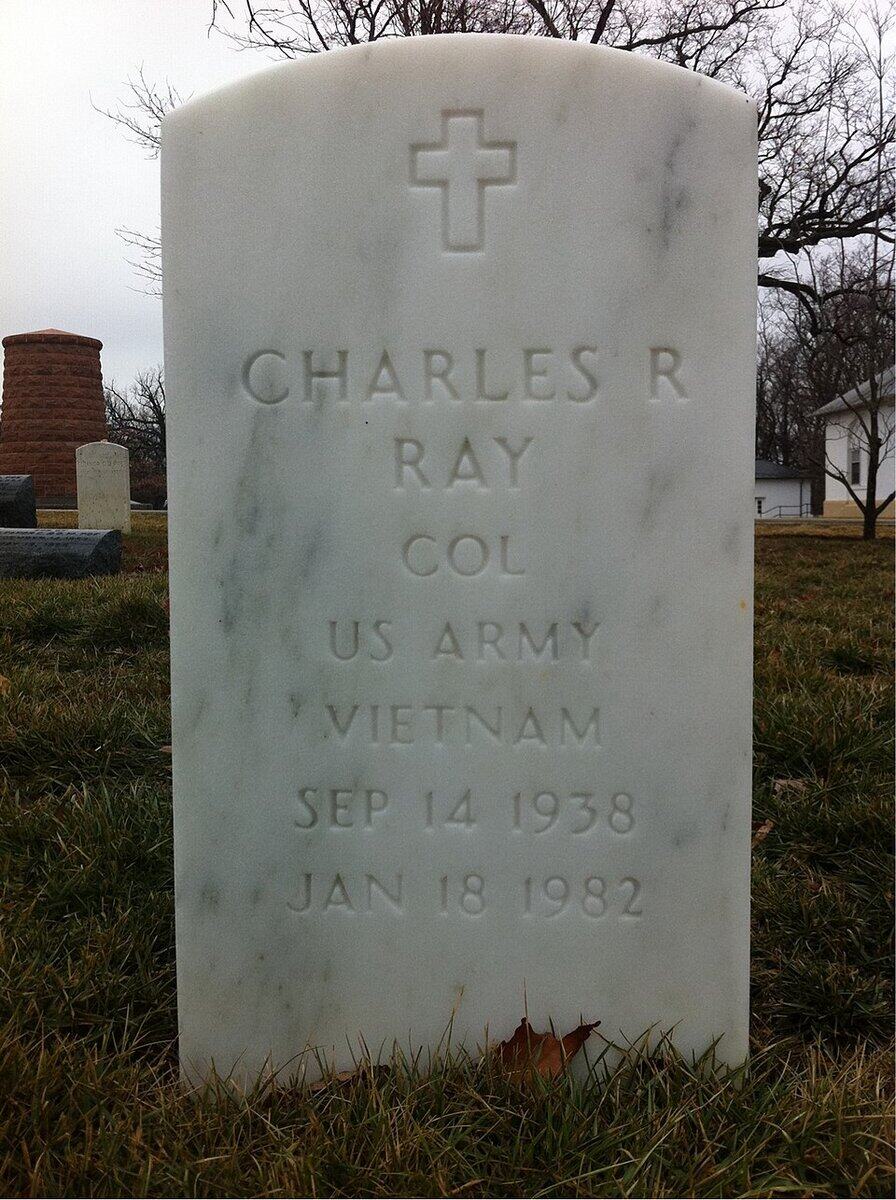

Christian A. Chapman served as Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) in Paris from 1978-82 and describes how he was the target of an assassination attempt. Robert B. Duncan served as Economic Counselor in Paris from 1978-82 and describes how terrorists almost blew up Embassy Paris. Philip Brown was Assistant Information Officer at USIS in Paris from 1981-1986 and remembers military attaché Charles Ray, who was assassinated January 18, 1982 and promoted to Colonel posthumously by President Reagan.

Richard Ross was the Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer for the U.S. Information Service at the Embassy from 1979-1984 and describes a massive explosion near his apartment. Victor Comras was Consul General in Strasbourg from 1985-1989 and describes the attack on his predecessor, Robert Homme. All were interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy, beginning in 1989, 1990, 1995, 2003 and 2012, respectively.

You can also read about when the German terrorist group Red Army Faction targeted Consulate General Frankfurt. See other Moments tagged under Terrorism and Embassy Security.

“A young man tried to kill me in front of my house in Paris”

Christian Chapman

Deputy Chief of Mission, Paris, 1978-1982

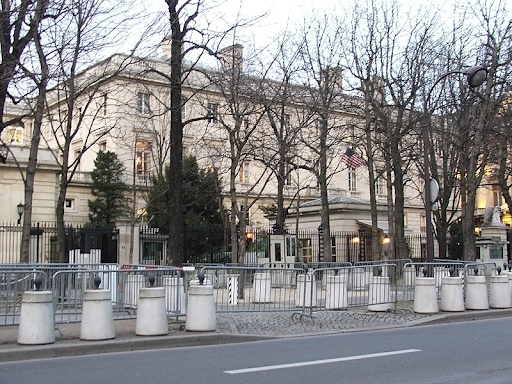

CHAPMAN: One word regarding an event that received wide publicity. On November 12, 1981, a young man tried to kill me in front of my house in Paris when I was the Chargé at the Embassy (at left). He failed. This attempt was the first of a series of terrorist attacks in France.

The previous September, we had received an intelligence report that teams of terrorists were leaving Libya to attack American embassies in Europe. While there are always alarmist messages in the air, we had taken this one seriously. I was Chargé at the time and immediately called a meeting of the Country Team [made up of senior representatives from the Embassy’s sections and agencies]. Together we steered a prudent course between ensuring that we would continue to do our job in France and maintaining tight security.

It’s not an obvious line: the tightest security is, of course, to close an Embassy down. What we did was to review all security measures already in place, tighten procedures and raise security-awareness among all personnel. This too is tricky because to keep the efficiency and energy of personnel up and doing their work, they must not be frightened into a state of fearful caution, but they also must be aware that there is a threat. The particularly difficult problem is that of families, the American school being our greatest concern.

In my own case, we changed my morning house-to-Embassy procedure by having the driver wait in the car several blocks away, allowing me to call him by radio when I was ready to go. This was the procedure I followed that November 12 morning.

As I stepped out of the door onto the broad sidewalk and cased the whole street, I noticed some 150 feet to my right a handsome young man, thirtyish, bearded, Middle Eastern, and dressed in black leather pants and jacket.

Not only that, but he had his hand inside his jacket. A pure grade-B movie scene.

I normally walk fast and was already halfway across the sidewalk when I saw the young man start to run towards me and heard the pops of his gun. My response was to run forward and hide behind the car waiting in the middle of the street. He fired six shots (as the police later determined) and then quietly walked away. No one tried to stop him as none of the witnesses, including us, was armed and someone had cried from a window across the street that he had an accomplice.

It did not take long for a flood of folks to invade the house: police officers, prosecutors, and of course our own security people. The police process was launched.

The problems then were first to communicate what had happened to all personnel in order to avoid false rumors creating a climate of fear, to review again all aspects of security, and to deal with the media that were soon clamoring for news. The Country Team is a wonderful mechanism of communication and consultation. We held a meeting as soon as I returned to the Embassy. I described what had happened; we discussed security once more; and for the time being, we decided not to close any U.S. facility, but simply to tighten procedures. And to meet together every day until we had a better appreciation of the situation facing us.

To handle the media, I decided to hold a press conference that very morning in order to set the record straight and to limit the public pressure on all of us. There was quite a turnout of news people, technicians, still and TV cameras. It was a slow news day, and this conference was the top item on Washington’s morning TV and radio shows. My ever-thoughtful secretary had fortunately called my wife immediately to forewarn her of the events.

But what was so striking was the transformation of this minor event into a world-wide real happening (Ah, the Information Age! It magnifies and distorts instantly.). Two months later, in January 1982, one of our Assistant Military Attachés, Lt. Colonel Charles Ray, was shot in the back of the head at close range on the sidewalk in front of his apartment building. In April, an Israeli diplomat, Jaacov Barsimantov, was murdered in front of his family as they left their apartment building.

Two months later, our Commercial Counselor, Rod Grant, and his family escaped a magnetic bomb that had been planted under his car….Finally, in 1984, the U.S. Consul General in Strasbourg, Robert Onan Homme, was shot and severely wounded. (See below)

The individuals who committed these crimes were not caught but through one of these stranger-than-fiction happenings, the chief of the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Faction, Georges Ibrahim Abdullah, was arrested in 1985 in a routine police check in a train after he was found with three different passports. He was tried but was sentenced to life imprisonment only after a long and tortuous trial.

[Note: George Ibrahim Abdallah (aka Salih al-Masri and Abdu-Qadir Saadi) was captured in 1984 and was sentenced to life in prison in 1987. He was released from France in January 2013 and deported to Lebanon, over the objection of the U.S. and Israel. Photo: Reuters]

The interesting point here is that the members of the LARF were Lebanese Maronites, Christians who had espoused the cause of the Palestinians and sought revenge against Americans and Israelis. As they worded a statement issued after the attempt against me: “The attack is directed at Reagan and his imperialist colleagues who are trying to destroy Lebanon.” A week following the attempt against me, a friend called and noted that November 12 is the feast day of St. Christian, an obscure Ukrainian monk who was murdered by robbers in the 12th century!

The day terrorists almost blew up Embassy Paris

Robert Duncan

Economic Counselor, Paris, 1978-1982

DUNCAN: The most dangerous assignment I’ve ever had was in Paris because that’s when we had the terrorist attack. Our Army attaché was gunned down on the sidewalk. A Libyan attacked our DCM, Chris Chapman. They said that we were being targeted, so they set up all sorts of special operations for us. At one point, they said they were going to have us accompanied.

Then we had the famous case of Rod Grant, the commercial counselor, saw the bomb under his car. This was the miracle of why American Embassy Paris continues to stand. We were having these terrorist attacks against American personnel. Rod Grant had a son who was going to UCLA. He and his father were having an argument. He was going to take him back to the airport to send him back to college. They came down the stairs.

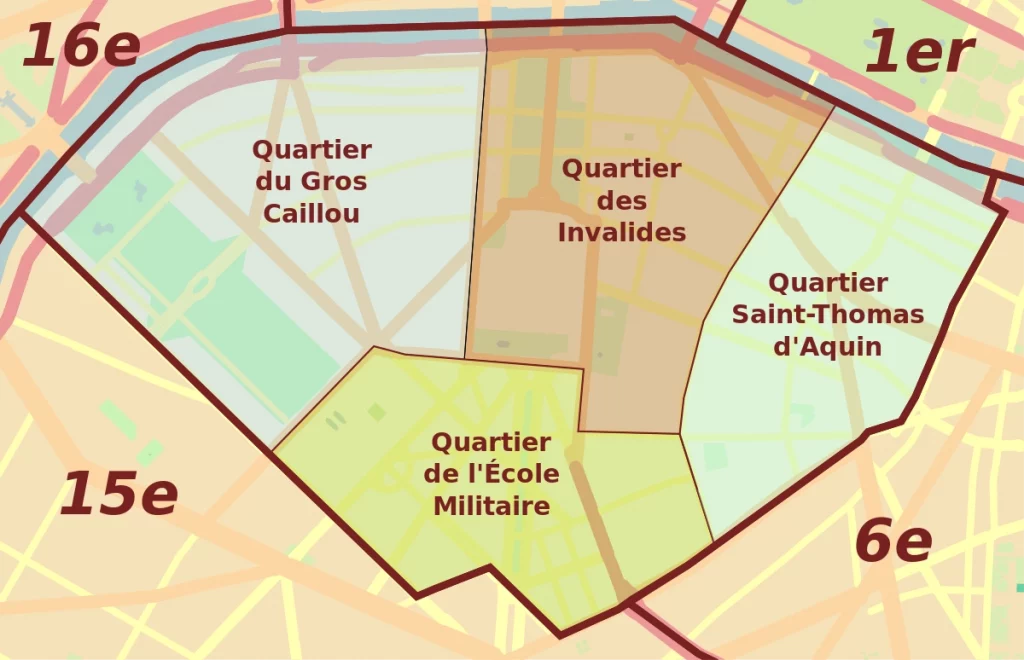

They were on the Avenue de la Bourdonnais in the 7th arrondissement. They came out of their apartment house and went over to the car. The 18-year-old son, who was an athletic type, was so aggravated at his father that when he got the trunk open, he threw his duffel into the trunk and slammed the trunk so hard that a magnetic bomb that had been put under the car dropped off into the street and they drove away to the airport.

Our assistant Air attaché, who lived nearby, was walking down the street, saw this thing and knew from his own experience what it was. So, they called the Parisian bomb disposal people. They came out.

According to one of the security people, the reason that what happened happened was because they violated the first rule of bomb disposal: That is, you don’t move the bomb until you diffuse it. They moved it and it exploded and took out windows on two sides of the avenue to the whole block of the Avenue de la Bourdonnais.

The thing of it was that the terrorists probably knew that Rod Grant parked his car in the basement garage of the embassy. So, the feeling was that what they had wanted was for him to drive his car into the basement and then have the thing blow up there. So, we would have lost our building on the Place de la Concorde. The fact that it took out all the windows on a whole block in the air, you could imagine what it would have done to the embassy.

The Assassination of Military Attaché Colonel Charles Ray

Philip C. Brown

Assistant Information Officer, USIS, Paris, 1981-1986

BROWN: Very early on, a couple of months into my presence there, the word came to the press office that shots had been fired at the DCM, Christian Chapman. He was the Chargé. He came out of his house in the morning to get into his car — I think he was being driven — and realized that someone was firing shots at him. Christian Chapman was as close to a French intellectual as you could find in the American Embassy, educated in the French or in the French tradition. But like a good American, he ducked behind his car; shots were fired but missed him, miraculously missed him.

He came to the embassy where I asked him for guidance; our phones were ringing off the hook. What had happened, etcetera? I asked him if he would be willing to speak to the French press and despite concerns from the security people, he was. I will never forget the scene as we allowed French journalists into the embassy and Christian Chapman occupying a position there on the second floor of the embassy where the Ambassador’s office was, a very elegant position.

He answered questions in both English and perfect French and basically the word that went out was that the American embassy Chargé d’affaires had ducked behind his car, the bullets had glanced off and he was safe. That was about all there was to it at that time. No clear cut information on who the assailant was or whatever.

Little did we realize this was thrusting us into a new age. In 1982, anyone who wanted just walked in the front door of the embassy. We didn’t have ID cards, badges. If there was any sort of control on who walked in the embassy, it was minimal.

Somewhere, not too long after that, we got ID cards. The French resisted this, particularly the more senior employees. Lucette, for example, was accustomed to French journalists coming in and having a chat with someone in the embassy, perhaps the way it used to happen in the State Department. It wasn’t just the attempted shooting of Christian Chapman that caused the change but it was part of the whole evolution at that time.

The Christian Chapman incident was November 12, 1981. It was two months later, January 18, that one of our military attachés, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ray walked out of his house and was not so fortunate. Someone walked up and shot him once in the head. He was assassinated, murdered right there in the streets. He was married with two children, roughly the same age as my children.

By that time, Evan Galbraith was there as Ambassador. We all assembled in his office and I can remember to this day, Ambassador Galbraith was very quick except at this point, he seemed to be a little bit paralyzed. What should we do?

We lowered the flag to half staff. I drafted a statement. He didn’t like the statement. He thought it was the bland kind of thing you say every time something like this happened so he came up with his own version. He not only issued it in writing but verbally as well. He said he was “revolted” by the cold-blooded murder. And he went ahead with a previously scheduled lunch with President Mitterrand.

The next day there was a funeral service at Notre Dame where Charles Ray was a regular parishioner. My job was to control and advise the French and other press on what they could and could not do in the service. So that was a big news making event.

It was not the only terrorism related incident we would have but it was the only time an American official would be killed while I was in Paris.

“That is not a car backfiring. That is an explosion!”

Richard Ross

Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Paris, 1979-1984

ROSS: We lived downtown. One Sunday night I went off to a famous Sunday night — you wouldn’t call it a salon, it was in an at-home that a guy named Jim Haynes had in Paris. He’s an American who was teaching at University of Paris VIII (Vincennes), who had sponsored all kinds of artists and had written a book or two and knew everybody; and everybody showed up at his house, and he cooked spaghetti—one of these things.

He lived in, literally, an artist’s studio with glass lights facing north.

I was coming back around 11:30 at night; and Mom—that is, to say Jane and the boys—we were downtown then in Saint Germain des Pres, a block from the church. I came up out of the Métro, and this is right where the [Café des] Deux Magots is. “Brasserie Lipp” is across the street, “Cazes Lipp” as they say.

There was this tremendous KA-BOOM!

I thought, “That is not a car backfiring. That is an explosion!”

So people ran out into the street—it was summerish I think—and looked down the street, and some people started running down the street. I started running too, and I then turned down Rue des Saints-Pères and then ran along a little street toward our house, and I saw smoke coming out from the building! (It was a five-story building from about 1890) I thought, “Oh, God! They got us!”….So I ran around and ran into the front door, and there was broken glass everywhere, and there was this car that was on fire. Our car was parked up the street on the curb.

By this time things had gotten so bad in Paris that a friend of ours who’s a military attaché got shot; the DCM had gotten shot at with the same gun they found out later; Israelis from their embassy had been killed; and there had been different kinds of threats; and somebody from the police had their feet and legs blown off trying to disarm a package that fell off a car that was at the economic officer’s house, Rod’s house—a package fell off when they drove away to the airport, and then the police went to disarm it, and it blew up and actually killed one guy; he died in the hospital later; it made him what they call a basket case kind of thing.

So I ran, and I thought, “Oh, my God!” I felt my hair standing on end. I’ve never felt that before. The electricity worked, and I did the code and got in the door and ran up the steps and banged on the door, and Jane opened it.

I said, “You’re alive! Oh, my God! How are the boys?”

She said, “You’re alive!”

I said, “I thought it was our apartment!”

She said, “I thought it was our car!” because our car was all messed up.

There were people running up and down the street and below us was the “commissariat de police” (local police station), which they only open during weekday hours; it was like a little branch police office, “su commissariat.” Somebody had put a bomb in the door and blown in the police station and blown up the car, and it cracked the building, and it blew all the glass out of all the windows.

We closed the metal grates which they have in Paris, to kind of make it darker in the kids’ room (they slept in the same room). Glass blew all across the floor, but it didn’t cut them because of the way the blast came. Jane had just gotten into bed, and she said she was halfway asleep and saw a white thing in front of her eyes. You know it’s funny how you can. The whole room lit up. We stayed up all night….

Q: Who set off the bomb?

ROSS: It was supposedly Corsicans, a Radundi Cassio, to get back at the police for accidentally killing a 16-year-old girl in a dope bust. This was the story, that it was not against the American embassy or against us, but we didn’t know it at the time. That was the conventional wisdom on it….

“Terrorism became a daily occurrence in France during this whole period”

Victor Comras

Consul General, Strasbourg, 1985-1989

COMRAS: This was a time when France was under great trauma from terrorism. Although it was very exciting to be going to Strasbourg in 1985, there were some downsides to be considered. One of the most significant downsides related to terrorism concerns for me and my family.

Our predecessor, Bob Homme, had been shot by terrorists. He was shot by a member of the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Faction as he left his house (the residence).

This happened one morning just as he was leaving the residence to go to the Consulate. He survived, but was very badly wounded. He was shot while backing out his car.

There was a person repairing a motorcycle out in front of the house. As he pulled out the person got up and shot him through the window. Luckily for Homme, just a week before the Consulate had installed a gate opener so that he could remain in his car while exiting. If he had gotten out of his car to open or close the gate, he probably would not have survived. As it turned out, the terrorist had to shoot him through the car window. He was hit several times. The bullets came within millimeters of hitting vital organs. One bullet grazed his head.

Fortunately, he had turned at that precise second or the bullet would have entered his brain. Fortunately for him and his family and for us all, he survived and the wounds ended up being neat and repairable.

The person who fired the shots was never caught. The ringleader of the group was caught several years later.

But, at the time we were in Strasbourg, both the Consulate and the Residence were under threat and the French government provided us special 24-hour protection. This included assigning two special GPN guards to accompany me whenever I left the residence or the Consulate.

During this same period we lost our military attaché in Paris to assassination by terrorists. There had also been an attempt against our DCM. A car bomb set under his car didn’t go off. However, and very sadly, a French policemen was killed when the bomb was being removed.

Q: What was behind this?

COMRAS: There were so many factors going on in that period of time. The situation in Lebanon was very unsettled with Western interventions. There were a number of different homegrown terrorist groups also operating in the area including – the Red Army factions, the Red Brigade, as well as other terrorist groups in Germany and Italy. There were also a number of groups associated with one or another cause or faction or another in Algeria. Of course there were also issues related to the Palestinians, and to French interventions in Chad.

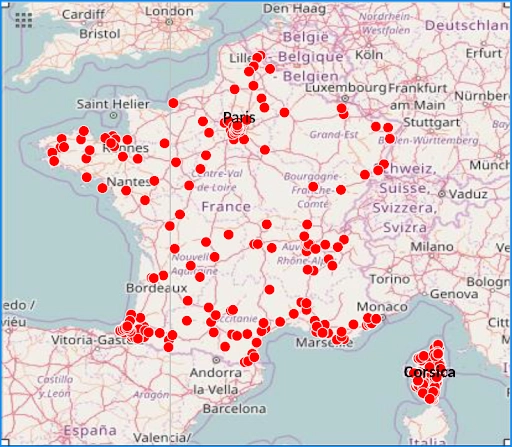

Terrorism became a daily occurrence in France during this whole period with bombs going off in trash cans, car bombs, and various other things. It was a very difficult period from 1985 through 1989.

Q: This having happened to your predecessor, what did they do for you?

COMRAS: U.S. and French authorities took the issue of our security very seriously following the attack on Homme. They took a number of steps to tighten the security of the consulate and the residence. We were also given an armored car and a chauffeur. The French police set up a police box in front of the residence. They also gave us constant 24-hour close-on protection. They accompanied us everywhere I and my family went. This was particularly the case during the first two years. It tapered off a little after that. We also had security guards at the Consulate and residence hired by the U.S. government.

It was something to which we had to adapt. The French had a team of specially trained policemen that were specially assigned to us. Over time we got to know them all well. They got to know us well. I don’t know if it was the best from the security perspective, but we decided that the only way we could do this and be comfortable was by making them family. So, over time they became part of our family. So they got to know us and we them well enough that we were comfortable with them and they were comfortable with us. It worked well in that sense.

The 1986-87 Paris bombings and the high-profile trial of Georges Ibrahim Abdallah

Steve Kashkett

Counterterrorism Officer, POL section, U.S. Embassy 1986-1988

KASHKETT: As a result of a fortuitous traffic stop, French police in late 1984 arrested Georges Ibrahim Abdallah, the leader of the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Faction (LARF), a militant leftist pro-Palestinian group that had carried out a series of terrorist attacks in France over the previous three years These included the assassinations of U.S. Assistant Army attaché Charles Ray and Israeli embassy officer Yaacov Bar-Simantov in 1982 and the attempted assassinations of U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Christian Chapman in 1981 and the U.S. Consul General in Strasbourg, Robert Homme, in 1984. Considering that most of the targets of these attacks were American officials assigned in France, the U.S. government took a direct interest in making sure that Abdallah was tried and convicted.

When I arrived at Embassy Paris in early summer 1986 to serve as the counterterrorism officer in the political section – and having previously been assigned in Lebanon tracking militant groups there – the high-profile Abdallah case became my number-one priority. By that point, it was clear to us at the embassy that the French government, which was trying to avoid Middle Eastern terrorism against French targets, had absolutely no intention of aggressively prosecuting Abdallah. We made the fateful decision to constitute the U.S. government as a “partie civile”, a directly concerned civil plaintiff that has the right under French law to participate in a trial. In that capacity, we hired a prominent French trial lawyer, Georges Kiejman, to prosecute the case on behalf of the U.S government.

In the fall of 1986, as the February 1987 trial date approached, Paris was hit with a series of lethal terrorist bombings at public places claimed by a nebulous coalition of groups demanding the release of Middle Eastern political prisoners in Europe, but it was widely understood that they were talking primarily about Georges Ibrahim Abdallah. These bombings, which killed 15 people and wounded hundreds, created a deep sense of fear and panic in the capital, as well as foreboding about the upcoming Abdallah trial. The nervous, risk-averse French government dropped all pretense of letting the state prosecutor build a strong case.

By contrast, the Reagan administration, eager to make a statement of U.S. determination to fight terrorism, gave us to green light to take over the prosecution. Under heavy security, we brought former Consul General Homme and Sharon Ray, the widow of Lt. Col. Ray, back to Paris to testify. I worked closely for several months with our French lawyer Kiejman to put together all of the compelling evidence of LARF responsibility for those assassinations and attempted assassinations, which the French prosecutor had failed to do. We compiled persuasive evidence that Abdallah had ordered those attacks and probably carried out the shooting of Lt. Colonel Ray himself. Several of the others, including the Barsimantov assassination and the unsuccessful shooting of Consul General Homme, appeared to have been carried out by Abdallah’s girlfriend Jacqueline Esber.

The “smoking gun” came in the middle of the week-long trial, when I got a call at home late one evening from Kiejman, who said that he and his assistant had stumbled across “something very important”. It turned out to be a Strasbourg map found in a LARF safe house detailing driving instructions to CG Homme’s residence in Abdallah’s handwriting. We spent that night frantically going back and forth with Washington trying to get a quick FBI handwriting analysis to confirm that it belonged to Abdallah.

On the final day of the trial, the three-judge panel found Georges Ibrahim Abdallah guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment. This was front-page news all over Europe and a major public victory for U.S. counterterrorism. On the day after the trial, the State Department evacuated me from Paris for security reasons and only allowed me to return a month later after a lengthy threat assessment. Kiejman went on to become the Justice Minister under French President Mitterand three years later.

Abdallah remains in French prison until this day and is, I believe, the longest-serving Middle Eastern terrorist convict jailed in Europe.